One of the many challenges that people face when adopting a Paleo diet is dealing with the confounding factor of additional food sensitivities. Sometimes these sensitivities are known (perhaps you had allergy testing done at some point or react so violently to certain foods that it was a no-brainer). Sometimes these sensitivities are unknown and make it frustrating when we don’t experience the instant improvements to our health touted by so many Paleo enthusiasts. One such sensitivity is FODMAP-intolerance (also referred to as fructose malabsorption). This isn’t a food sensitivity in the sense that there is any sort of immune reaction to these foods. Instead, it is a case of a person who cannot properly digest the fructose (and longer sugar molecules containing fructose) in these foods.

The term FODMAP is an acronym, derived from “Fermentable, Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides and Polyols”. FODMAPs are short chain carbohydrates rich in fructose molecules which, even in healthy people are inefficiently absorbed in the small intestine. I know you’ve heard the limerick “beans, beans, the magical fruit…”; the punchline refers to the large amount of FODMAP carbohydrates in beans (or any of other vegetable that has a reputation for being “gassy”) that are only partially absorbed in the small intestine. When this excess fructose enters the large intestine, which is full of those wonderful beneficial bacteria we love so much, they feed the bacteria allowing for overgrowth of bacteria and excess production of gas. The presence of FODMAPs in the large intestine can also decrease water absorption (one of the main jobs of the large intestine). This causes a variety of digestive symptoms, most typically: bloating, gas, cramps, diarrhea, constipation, indigestion and sometimes excessive belching. In individuals with FODMAP-intolerance, a far greater portion of these sugars enter the large intestine unabsorbed, causing exaggerated symptoms. In fact, some researchers believe that Irritable Bowel Syndrome is purely a case of FODMAP-intolerance 1,2.

Carbohydrates, which are just chains of sugar molecules, are broken down into individual monosaccharides (a single sugar molecule) by digestive enzymes in the small intestine (actually, this sugar digestion process begins with the salivary amylase enzyme in the mouth when you chew, but it continues all the way through the small intestine). Monosaccharides are then absorbed into the blood stream by first being transported through the cells that line the small intestine, the enterocytes. Enterocytes have specialized transporters, or carriers, embedded into the membrane that faces the inside of the gut. These carriers bind to specific sugar molecules and transport them into the cell (where the cell can either use those sugars for energy or transport those sugars to the other side of the cell where they can easily enter the blood stream). FODMAP-intolerance may be due to lack of digestive enzymes required to break longer chains of carbohydrates down to their individual monosaccharides and/or due to an insufficient amount of these carbohydrate carriers, specifically the carrier called GLUT5, which is the specific carbohydrate carrier for fructose (why this is also called fructose malabsorption).

FODMAP-intolerance means that large amounts of dietary fructose and longer carbohydrate chains that are rich in fructose are problematic. These longer, fructose-rich carbohydrate chains are called fructans (inulin, which is a type of fiber, is also rich in fructose and problematic for those with FODMAP-intolerance). Sugar alcohols, called polyols, (sorbitol is an example) are additionally problematic because these sugars have the ability to block GLUT5 carriers (and if you’re working with a deficiency, that’s really not helpful!). Why do some people develop FODMAP-intolerance? Researches don’t know yet. It may be a reaction of the body to high fructose and fructan consumption with the Standard American Diet. It may be a side effect of a very distressed and/or leaky gut. There are also very likely to be genetic factors at play. The good news is that, for many, as their gut and bodies heal, their ability to digest and absorb these sugars improves.

When it comes to modifying your diet to address a suspected FODMAP-intolerance, dose is the key. The type of FODMAP may be important for some people. Some people are more sensitive to the fructose and polyols (due to GLUT5 carrier deficiency) while some are more sensitive to fructans (due to digestive enzyme deficiency). Some people are sensitive to both. How much you can handle is very individual and is likely to change as your gut heals. There are medical tests available to diagnose fructose malabsorption, however an elimination diet approach is more reliable. Research has shown that the removal of FODMAPs from the diet is beneficial for sufferers of irritable bowel syndrome and other functional gut disorders 1.

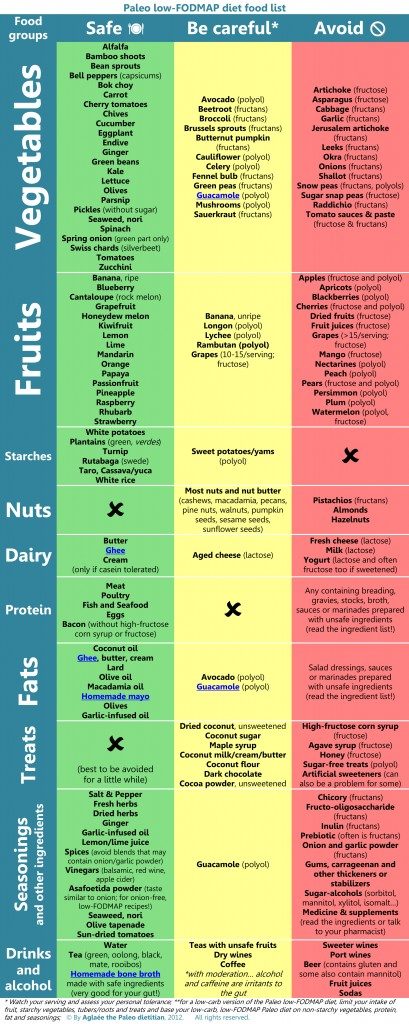

The following table was created by Aglaée the Paleo Dietitian, and is posted with her permission. It breaks down common foods into three categories: safe (very low to no FODMAP), be careful (low to moderate FODMAP), and avoid (high FODMAP). It also contains which kind of FODMAP is richly present in each food in parentheses (helpful for those who are more sensitive to one versus the other). (Aglaée told me that this table is likely to be updated in the near future. I will repost the edited version when it becomes available. You can see the original table here: http://www.eat-real-food-Paleodietitian.com/support-files/Paleo-fodmap-food-list.pdf)

As you can see from this table, many of the moderate to high FODMAP foods are foods that we typically increase consumption of when adopting a Paleo diet. How frustrating for those who experience an increase in gastrointestinal symptoms when they adopt a Paleo diet compared to so many who find instant alleviation of symptoms! If you suspect (or know you have) FODMAP-intolerance, I recommend eliminating all food sources of FODMAPs from your diet for a couple of weeks. If you are sensitive, you should notice a fairly dramatic effect on your digestive symptoms. You can try reintroducing some of the lower FODMAP fruits and veggies and see if your symptoms return. In many cases, following a gut-healing protocol (as outlined in this post, this post or in the book Practical Paleo) will improve digestion of FODMAPs and they can be reintroduced carefully but successfully.

It is very important to note that the symptoms of FODMAP-intolerance are virtually identical to the symptoms of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). The reason for this is that these two conditions are highly related. The difference is simply a matter of location, larger versus small intestine. Without testing it can be difficult to discern which of these Paleo diet modifications to try first (for more information on SIBO, read this post). Even more confusing, FODMAP-intolerance may or may not be linked to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. In some cases, the unabsorbed sugars caused by FODMAP-intolerance will lead to an environment in the small intestine where bacteria will grow, thus causing SIBO. So, you may have SIBO without FODMAP-intolerance, you may have FODMAP-intolerance without SIBO, or you may also have both. If you have digestive symptoms and are unsure which condition is the problem, then, I’m sorry to say that you’ll need to either have some tests done or follow the diet restrictions for both. After a period of a couple of weeks, you can try adding in either the starchy vegetables eliminated in the modification for SIBO or some of the FODMAP fruits and veggies (choose whichever food you miss the most). It should be clear fairly quickly which foods are problematic. Also note that both of these conditions are likely to resolve completely with continued elimination of these foods (although in some cases this will take 6-12 months or even longer), so you may find that you can add everything back in and your symptoms don’t return (fingers crossed!)

1 Gibson PR and Shepherd SJ. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010. 25(2):252-8.

2 Born P Carbohydrate malabsorption in patients with non-specific abdominal complaints World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2007, 13(43): 5687-5691