Regulating blood sugar levels is a key feature of the Paleo diet. In fact, this may be the critical mechanism responsible for the observed benefits of a Paleo diet in managing diabetes that has been proven in clinical trials. Generally, blood sugar levels are well regulated as soon as we focus on eating a variety of meat, seafood, eggs, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds (click here for Paleo Diet basics).

But, it’s human nature to find ways around the rules. A huge variety of recipes for Paleo-friendly, grain-free, dairy-free baked goods have found their way onto blogs (mine is no exception) and cookbooks (again, mine too). And a huge variety of pre-made, packaged sweet treat products are now available for sale, making getting a treat even easier. I really do believe that there is a place in our diet and our lives for the occasional treat (read this post for more), but that doesn’t mean that anything goes. And even if a treat is occasional, the ingredients matter.

Some ingredients (like emulsifiers) are uniformly recognized as being unhealthy choices. For others (like almond flour), there’s some pros and cons to consider in determining whether they are a good choice for you as an individual. And yet other ingredients are very unhealthy choices but are erroneously promoted as healthy alternatives to sugar! These ingredients are finding their way into recipes and packaged treats marketed to the Paleo community–and that is the reason for this post. There’s a concept that if a Paleo treat is made with a sugar alternative, and is thus “low-carb” or “low glycemic index”, that that makes it a good choice for a more frequent indulgence. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Alternatives to Glucose

Any food that causes elevated blood glucose is not conducive to health. The detrimental health impact of high blood glucose levels and high blood insulin levels are detailed in The Paleo Approach. Because of the direct link to diabetes and obesity, this is also becoming public knowledge.

Because excessive glucose consumption is so problematic, there has been a surge in low glycemic- index sweeteners, heavily marketed to diabetics and those on low-carb diets, which fall into three categories:

- Sugars that do not impact blood-glucose levels as quickly or substantially as glucose or glucose- based starches, which are marketed as low-glycemic-index sugars (fructose, inulin)

- Sugar alcohols (sorbitol, xylitol, erythritol)

- Nonnutritive sweeteners, including acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, and sucralose, as well as the “natural” sugar substitute stevia

Our bodies are not designed to metabolize these sugars in the large quantities found in processed foods. Yes, even foods and tabletop sweeteners that are marketed as “natural sweeteners” (such as agave nectar and stevia) are not actually natural for our bodies. In most cases, consuming these glucose substitutes is more harmful than consuming glucose itself. I will discuss sugar alcohols and nonnutritive sweeteners in an upcoming post. For now, let’s focus on the detrimental health effects of excess fructose.

The Scourge That Is Fructose

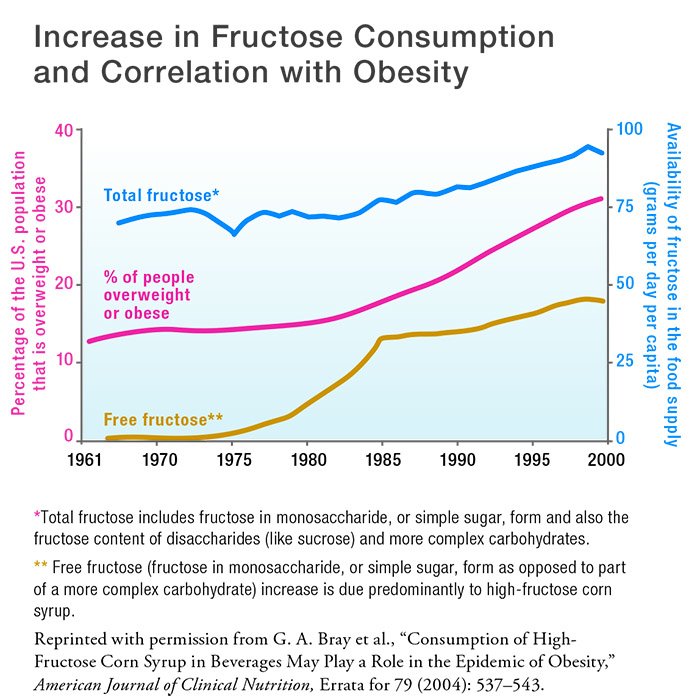

Fructose is probably the most destructive and pervasive non-glucose sugar. Because of the increase of high-fructose corn syrup in manufactured and processed foods, in addition to the increase in refined-carbohydrate consumption in general, the human diet has never been so full of fructose. For most of human history, people consumed about 16 to 20 grams (about half an ounce) a day, largely from fresh fruits. However, the average now is 85 to a 100 grams (as much as three and a half ounces) a day!

Fructose increases blood-triglyceride concentrations and, when ingested in large amounts as part of a hypercaloric diet, causes insulin resistance, stimulates appetite, and causes weight gain. In fact, the consumption of large amounts of fructose has been conclusively linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Fructose is digested and absorbed differently than glucose is. When sugars or starches enter the digestive tract, they are first broken down into simple sugars (monosaccharides such as glucose and fructose) by digestive enzymes. Glucose is transported into the body

high up the digestive tract and requires sodium for transport across the gut barrier. By contrast, fructose is absorbed farther down in the duodenum and jejunum and does not require sodium for transport. After absorption, both glucose and fructose enter the blood

and travel to the liver or other tissues in the body.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Fructose both enters the cells and is metabolized differently than glucose is. In most circumstances, glucose requires insulin in order to enter the cell. Insulin binds to and activates the insulin receptor, which in turn signals to the cell to increase the number of glucose transporters (called GLUT4) on the cell surface. By contrast, fructose enters cells via a different transporter (called GLUT5), which does not depend on insulin. While glucose can be readily converted into energy (that is, metabolized) by any cell, fructose metabolism occurs predominantly in the liver. Glucose and fructose are metabolized by many of the same enzymes, although the end products are very different. Glucose metabolism is a tightly controlled conversion from glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, which can then be used for ATP production or converted into glycogen or triglycerides for storage. Fructose, on the other hand, is first converted to fructose-1-phosphate, which is then converted into a type of simple sugar called a triose, which can be used in glycogen synthesis, but once glycogen stores are replenished, trioses provide a relatively unregulated source of precursors for triglyceride synthesis. This means that, when large amounts of fructose are ingested, excessive production of triglycerides results, which contributes to insulin resistance.

There is also evidence that fructose, but not glucose, may cause liver damage by facilitating the passage of endotoxins across the gut barrier. It remains unknown whether this is by directly affecting intestinal permeability or by altering the composition of the gut microflora. In a study in which fructose was injected into small blood vessels in the connective tissue around the gut in rats (mimicking fructose absorption from food), fructose increased inflammation thanks to oxidative stress. In another study, fructose was shown to increase cell surface molecules in the cells that line blood vessels (endothelial cells), which regulate inflammation. Some cancer cells also preferentially utilize fructose for energy, and high-fructose diets have been linked to increased cancer risk.

Yes, that’s a lot of bad stuff that fructose does.

But Some Fructose is Healthy…

That said, avoiding all dietary fructose is not necessary. In fact, moderate amounts of fructose are probably beneficial. For example, small quantities of fructose can actually reduce blood-glucose levels in response to glucose consumption and improve insulin sensitivity. It is simply the overconsumption of fructose from either concentrated food sources or excessive carbohydrate intake that you need to worry about.

So, how much fructose is healthy to consume? Studies show that optimal fructose consumption is between 10g and 20g per day. That’s right, it’s healthier to get 10g per day than none. And, over 50g per day is when the harmful effects start to kick in (see Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?).

This means that it’s not as important to avoid fructose found in whole foods like fruit and root vegetable, so much as it is important to avoided added fructose. That being said, it is possible to overdo fructose consumption even from whole food sources. It’s yet another case of “consume in moderation”. The trick is actually accomplishing that.

How To Moderate Fructose

I recommend avoiding all fructose-based sweeteners. These are all unnecessary sources of excess fructose and will very quickly send your dietary fructose intake skyrocketing. And contrary to what some people claim, they will not make your Paleo-friendly baked goods a healthier choice.

High-fructose corn syrup is not the only concentrated source of fructose to watch out for. The following are all sweeteners composed largely of fructose:

- Agave nectar contains an average of 70 percent fructose and as much as 90 percent.

- Inulin Fiber is an ingredient finding its way into many tabletop sweeteners. It is which is a high-fructose-content fiber and thus breaks down into fructose in the digestive tract.

- Yacon syrup is largely composed of inulin fiber.

- Chicory Root Sugar is another sweetener composed primarily of inulin fiber.

- Coconut sugar/nectar (or palm sugar/nectar) is also purported to be largely inulin fiber as well. Note, however, that there are conflicting reports showing that the sugar composition of coconut sugar is actually not much different from cane sugar, i.e., sucrose.

- Sucrose (table sugar which can be derived from sugar cane or sugar beets, but which is also the dominant sugar in molasses and maple syrup) is a disaccharide composed of one glucose and one fructose molecule. Although far preferable as a sweetener choice for your occasional treats, in large quantities, sucrose still provides excessive fructose.

Fruit in moderation is endorsed on the Paleo diet. However, excess fruit consumption can also contribute to excess dietary fructose. How much fruit can you eat to keep your fructose intake moderate? Depending on the type of fruit, two to four servings per day will generally keep fructose intake in the healthy ten-to-twenty-grams-per-day range. However, watch out for very high fructose content fruits such as mangoes (30g of fructose per mango!), and even pears and apples (13g of fructose per apple!). And keep in mind that some starchy vegetables also contain fructose (1 sweet potato contains 2.5g of fructose). To help you make the best choices, the fructose content of fruits and vegetables can be found in the nutrient tables on pages 355–389 in The Paleo Approach, also available as a free download here.

What about other simple sugars?

Glucose and fructose are by far the dominant monosaccharides (simple sugars) in the human diet. There are three other naturally occurring monosaccharides: galactose, xylose, and ribose. Galactose is one of the monosaccharides that makes up lactose (the other is glucose), which is the primary sugar found in dairy products. Galactose can bind nonspecifically to proteins and lipids, and for that reason the body quickly converts it into glucose. Xylose and ribose are not found in significant quantities in our food supply (xylose is found in wood; ribose is actually found in all living cells, but there’s not enough of it in food to contribute much to the carbohydrate content).

Take-Home Message

Fructose and fructose-based sweeteners are not your friend. And if you have adopted a Paleo diet but aren’t seeing the results you were expecting, excess fructose consumption could be why. Whether you’re going to town on fresh fruit, or overindulging in treats with the excuse that it’s make with whole food, grain-free, dairy-free ingredients, excessive fructose consumption can be hurting your health and holding you back.

I know that I have yet to post why sugar alcohols and nonnutritive sweeteners are also unhealthy choices (I have already discussed stevia here). But, I still want to emphasize this important message: There is no way to cheat desserts. I don’t recommend any sugar substitutes. As much as high glucose levels are detrimental, the body can actually handle real sugar (by which I mean sucrose) better than it can any of the manufactured or isolated substitutes.

Here’s the trick: keep your intake low. Gradually reduce how much sugar you add to your coffee, how much honey and maple syrup is in your baked goods, and how often you consume it. Yes, it takes commitment, but your taste buds will quickly adapt to a diet rich in nutrient-dense whole foods, and you will soon find that fruits and vegetables and the occasional minimally sweetened dessert will satisfy your sweet cravings.

Citations

Basciano, H., et al., Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia, Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005;2(1):5

Bray, G. A., et al., Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity, Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(4):537-43

Coss-Bu, J. A., et al., Contribution of galactose and fructose to glucose homeostasis, Metabolism. 2009;58(8):1050-8

Faeh, D., et al., Effect of fructose overfeeding and fish oil administration on hepatic de novo lipogenesis and insulin sensitivity in healthy men, Diabetes. 2005;54(7):1907-13

Glushakova, O., et al., Fructose induces the inflammatory molecule ICAM-1 in endothelial cells, J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(9):1712-1720

Liu, H. and Heaney, A. P., Refined fructose and cancer, Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(9):1049-59

Mattioli, L. F., et al., Effects of intragastric fructose and dextrose on mesenteric microvascular inflammation and postprandial hyperemia in the rat, JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35(2):223-8

Moshfegh, A. J., et al., Presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of Americans, J Nutr. 1999;129(7 Suppl):1407S-11S

Page, K. A., et al., Effects of fructose vs glucose on regional cerebral blood flow in brain regions involved with appetite and reward pathways, JAMA. 2013;309(1):63-70

Payne, A. N., et al., Gut microbial adaptation to dietary consumption of fructose, artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols: implications for host-microbe interactions contributing to obesity, Obes Rev. 2012;13(9):799-809

Shapiro, A., et al., Fructose-induced leptin resistance exacerbates weight gain in response to subsequent high-fat feeding, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295(5):R1370-5

Tappy, L., et al., Fructose and metabolic diseases: new findings, new questions, Nutrition. 2010;26(11- 12):1044-9

Teff, K. L., et al., Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2963-72

Vos, M. B. and Lavine, J. E., Dietary fructose in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2525-31

Looking for more?

Love reading my science posts? Then you’ll love reading The Paleo Approach! My New York Times bestselling book, The Paleo Approach is a complete guide to using diet and lifestyle to manage autoimmune disease and other chronic health conditions. It answers all of the whats, the whys, and the hows!

Love reading my science posts? Then you’ll love reading The Paleo Approach! My New York Times bestselling book, The Paleo Approach is a complete guide to using diet and lifestyle to manage autoimmune disease and other chronic health conditions. It answers all of the whats, the whys, and the hows!

Find The Paleo Approach at:

- All major online retailers, including Barnes&Noble, Target, Walmart, and Amazon.com.

- Costco

- Indiebound

- Book Depository