When we think about the effects of chronic stress, we think of cortisol. We think of weight gain, especially around the middle. We think of headaches and depression and anxiety. We think of poor sleep quality. Those of us who are very knowledgeable about health and nutrition think of increased cardiovascular disease risk.

Not many of us think about PMS, low libido, heavy or irregular periods, or amenorrhea. Or how disruption in sex hormone levels can lead to low thyroid function and osteoporosis. Or infertility. But those are also consequences of chronic stress for women.

As you’ve probably heard the likes of Robb Wolf and Diane Sanfilippo say “writing a health book is one of the worst things you can do for your own health“. When I completed my first book, The Paleo Approach, I suffered a complete health crash. The morning after the book was finally submitted to the printer, I woke up with pneumonia. I had three infections over the next six weeks. I gained 20 pounds in the months leading up to finishing The Paleo Approach, and the weight didn’t magically melt off when the book was done. I was getting plenty of sleep but was still tired all the time, relying on caffeine to get me out of bed. I was working out and watching myself get stronger, but my weight just kept slowly creeping up. And when I tracked my caloric intake, it didn’t make sense. I was getting 1800 calories per day (about what I still get now, but back in January I was gaining weight and now I’m losing it) and getting ample of all the essential micronutrients. This was a great example of how weight loss does not equal calories in versus calories out, but I wasn’t a big fan of being an example of what can go wrong with your metabolism….

So, I asked for help.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

I knew something was broken that diet and lifestyle couldn’t easily fix. It didn’t help that I went straight from finishing The Paleo Approach to working on The Paleo Approach Cookbook. So, I found a local functional medicine specialist, Dr. Lynn Flowers, who was an emergency medicine doctor for 20 years (but always interested in integrative and functional medicine) before deciding to open an anti-aging practice.

We ran a battery of tests. There was lots of good news (normal thyroid, great cholesterol, genetic testing showed no complications with ApoE or MTHFR). But, we discovered that I had adrenal insufficiency (more colloquially referred to as adrenal fatigue). I was low in cortisol and DHEA–all day. Not really a surprise. I had been burning the candle at both ends for months and it was obvious to everyone in my life that the stress was definitely getting to me. When your stress level is chronically elevated, eventually the adrenal glands (and availability of substrates) just can’t keep up. Chronically low cortisol is the direct result. [I will be talking about some of the other negative health effects of this stage of adrenal burnout in an upcoming post.]

What did surprise me was that I also had hormone imbalance. Low testosterone, low progesterone, normal estrogen (but this still creates estrogen dominance because the relative amount of estrogen to progesterone is so high).

So, how did that happen?

What is the link between stress and sex hormones?

And what happens when you’re chronically stressed?

And what happens when your sex hormones are out of whack?

To answer these questions, I first need to describe the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis (HPA Axis) and the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG Axis).

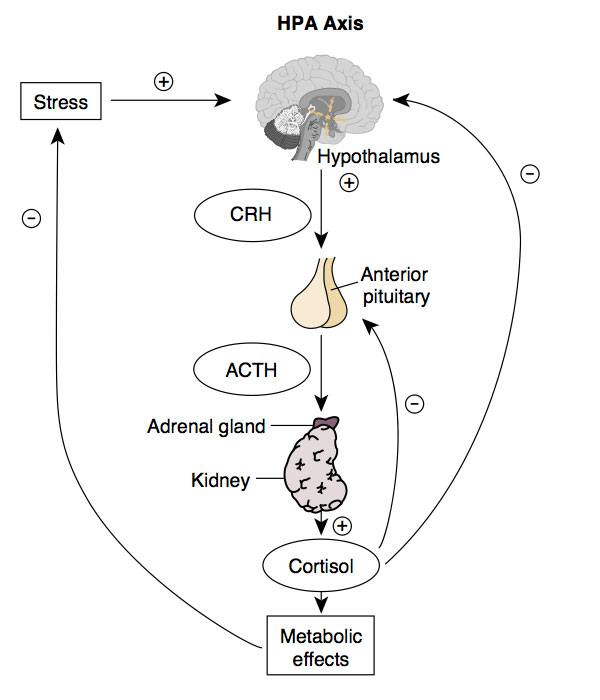

The HPA Axis

The HPA Axis is responsible for the flight-or-fight response. The hypothalamus (which receives signals from the hippocampus, the region of the brain that amalgamates information from all the senses and can thus perceive danger and make decisions) releases a hormone called Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to release a hormone called Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), which signals to the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol as well as catecholamines (like adrenalin).

The HPA Axis is responsible for the flight-or-fight response. The hypothalamus (which receives signals from the hippocampus, the region of the brain that amalgamates information from all the senses and can thus perceive danger and make decisions) releases a hormone called Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to release a hormone called Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), which signals to the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol as well as catecholamines (like adrenalin).

Cortisol has a huge range of effects in the body, including controlling metabolism, affecting insulin sensitivity, affecting the immune system, and even controlling blood flow. If you’re running away from a lion, all these effects (including the combined effects of catecholamines and some direct effects of CRH) combine to prioritize the most essential functions for survival (perception, decision making, energy for your muscles so you can run away or fight for your life, and preparation for wound healing) and inhibit non-essential functions (like some aspects of the immune system especially not in the skin, digestion, kidney function, reproductive functions, growth, collagen formation, amino acid uptake by muscle, protein synthesis and bone formation).

Cortisol also provides a negative feedback to the pituitary and the hypothalamus. It’s the body’s way of saying “hey, we got the signal that we’re supposed to be stressed now, thanks, we’re on it!”. If the stressful event has ceased (the lion gave up and left), this is what deactivates the HPA Axis. Of course, if a stressor is still being perceived (that lion is still there), the HPA axis remains activated. And this is why chronic stress (deadlines, traffic, sleep deprivation, teenagers, divorce, being sick, being inflamed, alarm clocks, bills, and internet trolls) is such a problem. All those essential functions suppressed by high cortisol never get a chance to be prioritized.

The HPG Axis

The primary role of the HPG Axis is to control reproduction, however it is also important for development (puberty and aging) and the immune system.

The primary role of the HPG Axis is to control reproduction, however it is also important for development (puberty and aging) and the immune system.

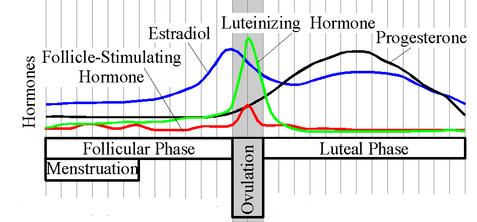

The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to secrete two hormones: Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). LH and FSH signal to the gonads produce estrogen and progesterone in women, and testosterone in men.

Because women’s bodies are particularly susceptible to effects of stress on sex hormone levels due to interaction between the HPA and HPG Axes, I’m going to focus from this point forward on the female HPG Axis.

Estrogen and progesterone also signal back to the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus. Generally, estrogen provides positive feedback, further stimulating the HPG Axis (although there are some mechanisms for negative feedback as well). Progesterone provides negative feedback, inhibiting the HPG Axis. In the menstrual cycle, the positive feedback from estrogen prepares the follicle in the ovary and the uterus for ovulation and implantation. When the egg is released, progesterone production inhibits the hypothalamus and pituitary, blocking the positive feedback from estrogen. If the egg is fertilized, the fetus takes over production of progesterone (why you don’t ovulate again while pregnant). If conception does not occur, progesterone productions starts to decline, which allows the HPG Axis to be stimulated, causing menses and the whole shebang to start over again.

This is an oversimplification. There are other hormones at play here. And all these hormones are controlling dozens of aspects of fertility and menstruation, as well as things like linking back to thyroid function, bone formation, and immune health. And it’s very important that these hormones cycle in rhythm with each other. And when one of the players is out of tune, the whole symphony sounds wrong.

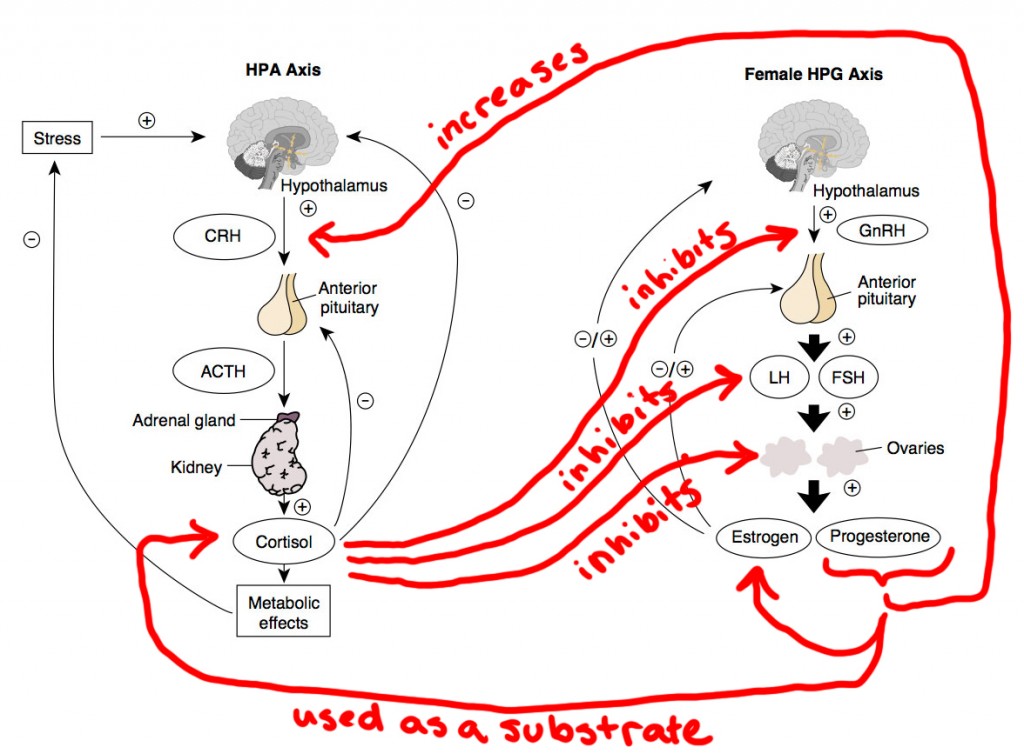

The Links Between the HPA and HPG Axes

The HPA and HPG Axes are not isolated endocrine systems. There’s crosstalk. Plenty of it. For instance, progesterone activates the HPA axis. This is probably part of the metabolic controls, shift in immune system, and shift in the body’s resource priorities during pregnancy. Probably why we also tend to have such strong food cravings in the days leading up to our periods starting.

But the links are more insidious than food cravings. Cortisol inhibits the HPG Axis at every point. It reduces the production of GnRH by the hypothalamus. It reduces the production of FSH and LH by the pituitary gland. It suppresses ovary function, reducing estrogen and progesterone secretion. This is because, if you are running away from a lion, reproduction is just not a priority. The body takes those resources and uses them for immediate survival.

But, what if the lion never stops chasing you? When you are chronically stressed and especially if your stress level is high (and you aren’t spending time outside, and you aren’t active during the day, and you are staying up late and not getting enough sleep and using caffeine and sugar to get you through the day), it’s basically the same physiologic effect of chronically running away from a lion. Reproduction (and digestion, and bone formation, and growth, and parts of the immune system, and collagen formation etc. etc. etc.) never get prioritized.

So, if you’re chronically stressed, estrogen and progesterone can be decreased. But, what’s more, the body converts progesterone into cortisol. And into estrogen. And testosterone (a hormone that the female body still needs, albeit in much lower concentrations than in men). Yes, progesterone is a substrate from which cortisol and estrogen and testosterone are synthesized.

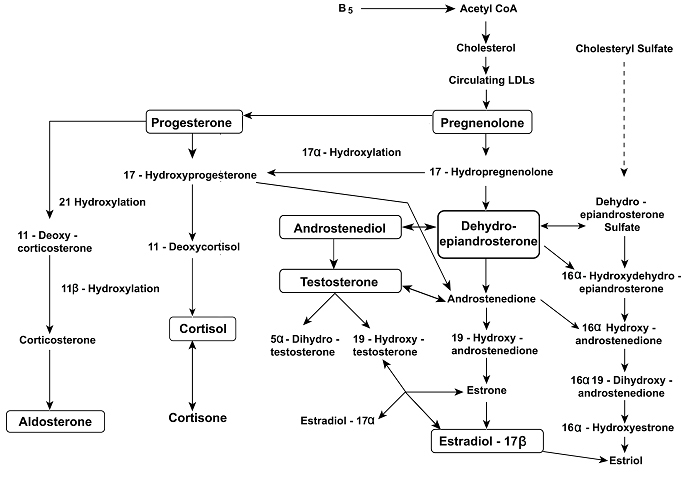

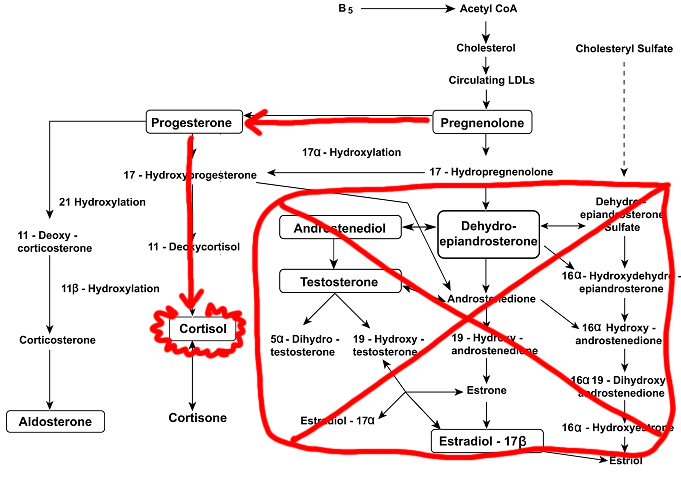

The following diagram shows how these essential hormones and their precursers and intermediaries are produced from cholesterol (yet again, the essential cholesterol!).

Yes, it’s complex. Here’s the important part: cholesterol (the backbone of all steroid hormones) is converted into pregnenolone. Pregnenolone is the converted into either DHEA or Progesterone. DHEA is converted into testosterone and estrogen. Progesterone is converted into cortisol. Still with me?

When the body is stressed, and it starts using up progesterone to make cortisol. It needs more progesterone, so it starts using more pregnenolone to make it. This is called pregnenolone steal. The HPA Axis is literally stealing the precursor for testosterone and estrogen (because pregnenolone is being used to make progesterone instead of DHEA) from the HPG Axis. What’s more? It’s using up all that progesterone to make cortisol.

By the way, this is also how chronic stress leads to low testosterone in men (one of the symptoms of which can be balding!).

There’s some extra complications here. When DHEA is low, the body tends converts testosterone and what little DHEA is being produced into estrogen. Environmental estrogens (like the phytoestrogens in soy or flax seed or walnuts, or like the xenoestrogens in some plastics) further increase estrogen. Nutrient deficiencies and lifestyle factors like type and frequency of activity can further influence exactly what hormones are getting produced and what hormones aren’t.

The Take-Home Message

The take-home message is this: chronic stress messes up your sex hormones.

How might you know if chronic stress has negatively impacted your hormones? Symptoms include: depression, fatigue, anxiety, hair loss, facial and body hair growth, headaches, dizziness, brain frog, poor memory, low libido, vaginal dryness, breast swelling and tenderness, fibrocystic breasts, thyroid disorders, osteoporosis, PMS, dry or wrinkly skin, urinary tract infections, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, weight gain (or resistance to weight loss), water retention, bloating, sleep disturbances, mood changes, irregular periods, loss of periods (amenorrhea), heavy periods, and infertility.

The natural follow-up question is what can you do if you think you have hormone imbalance as a result of chronic stress? Well, first and foremost: reduce your stress! Say “no”, ask for help, get enough sleep (at least 8 hours!), be active (but avoid strenuous activities), have fun, laugh, spend quality time with loved ones, orgasm, spend time outside, learn to meditate, make time for hobbies, and go for a walk. It’s time to give up caffeine and alcohol (temporarily!). Support liver health by eating a nutrient-dense diet that includes organ meats, seafood, and plenty of vegetables. I recommend The Hormone Cure by Dr. Sarah Gottfried and Sexy By Nature by Stefani Ruper as two excellent resources for optimizing diet and lifestyle to restore sex hormone balance.

This is serious stuff, and depending on a variety of factors, diet and lifestyle are sometimes not enough to set things straight. If you are going to consider hormone balancing therapy, know that it will not work if your diet isn’t clean (nutrient-dense Paleo, meaning a Paleo diet with a focus on organ meat, seafood, and vegetables, should suffice) and your lifestyle isn’t optimized (stress is low, activity level is moderate, and sleep is ample). Get tested and find a skilled medical professional to work with before you start messing around with supplements and taking hormones.

So, where am I now?

I’ve been working on reducing stress, prioritizing activity and sleep, and keeping my diet super clean along with hormone balancing therapy guided by Dr. Flowers for 5 months. The intense process of creating The Paleo Approach was a learning experience. And also, it was worth it: The Paleo Approach is a New York Times Bestseller that is helping tens of thousands of people reclaim their health. And even better, I was able to take those life lessons and apply them to finishing The Paleo Approach Cookbook. I just retested hormone levels and adrenal gland function but do not have the results yet. But, I’m losing fat, putting on muscle, have great energy, my skin looks amazing, my hair is thicker and I have much greater what Dr. Flowers calls sense of wellbeing. I’m pretty sure I’m not all the way back to normal yet, but I’m well on my way. And that feels really good!

Links to Diet

If you’d like to know more about the links between stress and hormones (and how diet might affect these systems), you may find my joint talk with Stacy Toth at the Ancestral Health Symposium 2014 to be interesting.

Do you need help finding a medical professional to work with?

My consultants, with specialties in dietetics, nutritional therapy, health coaching, and functional medicine, offer a variety of packages, from simple 1-hour consultations where you can ask your questions to full 6-month packages. They can work with you remotely (via Skype, phone and e-mail), and you can learn more about the individual consultants and services offered here:

I also recommend finding a qualified physician or alternative healthcare provider (many of whom can work with patients remotely) to work with via:

TPV Podcast, Episode 105: Mark Sisson

TPV Podcast, Episode 105: Mark Sisson