Want to see a debate more heated than politics or religion? Just ask a group of health-conscious people whether humans are natural herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores, and watch the fireworks begin!

The subject of whether humans are naturally suited for plant-only diets or meat-only diets (or something in between) has been the source of ongoing controversy and some very strong opinions. You’ve probably come across seemingly convincing arguments in support of every one of those positions, citing things like digestive anatomy, dental structure, and human history as reasons we’re herbivores… or carnivores… or omnivores! Confusing, right? For example, the Vegsource website claims we’re anatomical herbivores because of the amylase content of our saliva, our stomach size and shape, and our dental features (among other things), while Barry Groves of the Second Opinions website claims we must be carnivores because of our physiology, historical fossil evidence, and digestive activity (among other things)[I’ve heard these arguments among Paleo circles recently, the major impetus for me writing this series of articles]. And then we have Tom Billings of the BeyondVeg website claiming we must be omnivores due to our conversion and synthesis (or lack thereof) of certain nutrients, comparative anatomy of the human gut, and lack of any vegan “gatherer” tribes.

The subject of whether humans are naturally suited for plant-only diets or meat-only diets (or something in between) has been the source of ongoing controversy and some very strong opinions. You’ve probably come across seemingly convincing arguments in support of every one of those positions, citing things like digestive anatomy, dental structure, and human history as reasons we’re herbivores… or carnivores… or omnivores! Confusing, right? For example, the Vegsource website claims we’re anatomical herbivores because of the amylase content of our saliva, our stomach size and shape, and our dental features (among other things), while Barry Groves of the Second Opinions website claims we must be carnivores because of our physiology, historical fossil evidence, and digestive activity (among other things)[I’ve heard these arguments among Paleo circles recently, the major impetus for me writing this series of articles]. And then we have Tom Billings of the BeyondVeg website claiming we must be omnivores due to our conversion and synthesis (or lack thereof) of certain nutrients, comparative anatomy of the human gut, and lack of any vegan “gatherer” tribes.

The problem is, the justifications for each position sound convincing on the surface, but don’t always hold water when we look at them more closely. So, in this series of posts, I’ll be examining the issue of the “natural” human diet from a variety of scientific angles—using human evolutionary history and clues from hunter-gatherers (this article), comparative anatomy and human physiology (upcoming article)—and then piecing it all together to see what conclusions we can draw from the available evidence (upcoming article).

This is the first article I’ve ever written that really dives into detailed evolutionary biology, archeology and anthropology. I approach the Paleo diet from a biological and physiological point of view—I want to understand how the components of individual foods interact with our bodies at the cellular and molecular level to either foster or undermine health. To me, understanding what our Paleolithic ancestors ate and attributing their good health to their diet is not sufficient to prove that the Paleo diet is a superior approach to nutrition. Instead, I see understanding ancestral diets as the hypothesis—the proof is found in the tens of thousands of scientific studies that elucidate the roles of essential and nonessential nutrients in the human body, explain how functional compounds in our foods add to our health, and show that certain compounds in foods can be major problems for our health by causing inflammation, disruption hormones, or damaging the gut. When you evaluate food in this lens, you come up with the same thing: the healthiest diet is composed of seafood, high quality meats, vegetables galore, fruits, eggs, nuts and seeds.

This is the first article I’ve ever written that really dives into detailed evolutionary biology, archeology and anthropology. I approach the Paleo diet from a biological and physiological point of view—I want to understand how the components of individual foods interact with our bodies at the cellular and molecular level to either foster or undermine health. To me, understanding what our Paleolithic ancestors ate and attributing their good health to their diet is not sufficient to prove that the Paleo diet is a superior approach to nutrition. Instead, I see understanding ancestral diets as the hypothesis—the proof is found in the tens of thousands of scientific studies that elucidate the roles of essential and nonessential nutrients in the human body, explain how functional compounds in our foods add to our health, and show that certain compounds in foods can be major problems for our health by causing inflammation, disruption hormones, or damaging the gut. When you evaluate food in this lens, you come up with the same thing: the healthiest diet is composed of seafood, high quality meats, vegetables galore, fruits, eggs, nuts and seeds.

But the question of whether humans are meant to be herbivores or carnivores or some shade of omnivore in between is a very different question than what is the optimal human diet, although clearly these two concepts are related. And I think that in this case, a great deal of insight can be gleaned from looking at the evolution of man and at modern and historically-studied hunter-gatherer populations. Not to mention the fact that this is the source of so much misinformation on the subject! I will, of course, be rounding out this information with some comparative anatomy and physiology (and more myth busting) in my next article in this series, but for now, let’s start at the beginning… the beginning of man.

The Human Diet: A Timeline

Although there’s no good reason to throw on a loincloth and try to replicate everything our early ancestors did, studying what they ate (and how their diet shifted over the course of thousands or millions of years) can tell us a lot about the forces that shaped our genome and established our nutritional needs.

One way scientists figure out what early humans ate is through something called isotope analysis. Basically, different foods leave different carbon and nitrogen “signatures” in our bones and teeth after they’ve been ingested and incorporated into our tissues. Plants that use the C3 pathway of photosynthesis (like temperate-climate fruits, berries, nuts, leaves, and grains that thrive in wet environments) leave a different carbon signature than plants that use the C4 pathway of photosynthesis (like dry-climate grasses, sedges, roots, seeds, grains, and starchy underground storage organs [things like tubers and bulbs]).

So, scientists can gauge the proportion of C3 versus C4 plants that early humans ate by looking at different carbon measurements in fossil remains. Eating animals that consume C4 plants, like grass-grazing ruminants, can leave a carbon signature similar to eating C4 plants directly—so scientists have to use other methods to get a sense of whether the carbon came from plant or animal foods. Some of those methods include looking at nitrogen isotopes, which tell us about protein intake; examining archeological sites for tools and food remains; analyzing dental wear and tooth structure; and studying fossilized feces, called coprolites.

Carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis can also help differentiate between land-based and marine protein sources, legume and non-legume foods, and whether any animals consumed were herbivores or carnivores. I won’t pretend to understand all the detailed methodology that goes into this fascinating branch of science, but it does trigger my geek-dar pretty intensely! From these methods, scientists can paint a pretty decent picture of what our ancestors’ diets looked like, and how their eating patterns changed over the course of history:

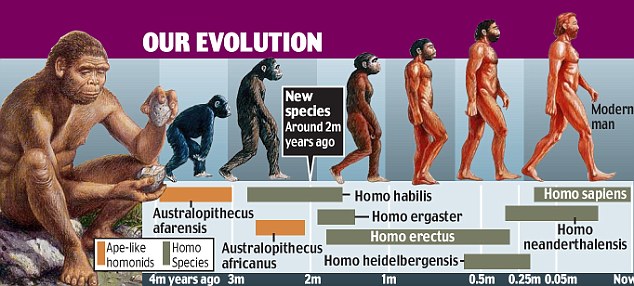

- From 4.4 million years ago to about 3.3 million years ago: the diet of our very earliest ancestors (after splitting with our last common ancestor with the chimpanzee) was almost identical to that of modern primates: lots of C3 plants in the form of fruits, nuts, and leaves, but virtually no evidence of C4 plant consumption.

- 3 million years ago: here we saw a major dietary shift, where dry-climate C4 plants (and possibly the animals that grazed on them, but there isn’t much evidence for that yet!) entered the diet of our early ancestors. Basically, hominins stopped relying on forest resources and started eating more foods derived from grasses and succulents, such as seeds and underground roots.

- 2.5 million years ago: we see the first indication of meat-eating among our early ancestors, although we can’t say for sure how much came from hunting versus scavenging.

- 2 million years ago: some human ancestors engaged in “persistent carnivory”—that is, deliberately and frequently eating animal foods (which isn’t to say that’s all they were eating!).

- 1.95 million years ago: our early ancestors were butchering and consuming aquatic animals such as turtles, crocodiles, and fish, as well as eating a variety of aquatic and shoreline plants.

- 1.9 to 1.8 million years ago: Homo erectus emerged, and experienced a simultaneous increase in brain size and decrease in gut size that suggests some important dietary changes were happening—namely, an improvement in diet quality (foods that were denser, more calorie and nutrient rich, and easier to digest). Unfortunately, we don’t know whether that improvement was from cooking or from advanced stone tool technology that made food processing easier, or both. And, we don’t know whether the increased energy density was from meat or from starchy plant foods like underground storage organs (USOs—which we’ll talk about in depth a bit later!), or both. Since fire evidence, vegetation, and sticks used for digging up roots don’t preserve very well in the fossil records, it’s really hard to determine the role of plant foods versus meat in the dramatic physical changes of Homo erectus, and we’ll probably be debating the issue for a long time into the future.

- 1.5 million years ago: there’s some sporadic (but super inconclusive) evidence that early human populations started controlling fire (in which case, cooking would make a lot of sense as a contributor to increased brain size and decreased gut size!), but the jury’s still out until we have more evidence to draw from.

- 800,000 years ago: we can say with certainty that early humans were controlling fire and cooking (both meat and dense plant foods), and cooked foods were becoming widespread in the human diet.

- 200,000 years ago: Homo sapiens appeared, which is the species that you and I (and all modern humans!) belong to.

- 30,000 years ago: high-energy plant food processing started to emerge, such as acquiring and preparing starch grains from various wild plants.

- 12,000 years ago: the dawn of agriculture arrived, and with it came the spread of controlled crops and animal husbandry. This caused a dramatic shift in the makeup and quality of the human diet: nutritional diversity went down, 50 to 70% of calories started coming from starch, and eventually, we were able to produce more food calories than we needed to sustain ourselves (which was a first for our species!).

- 9000 to 4000 years ago: genetic mutations for lactase persistence started popping up in certain European, African, and Middle Eastern populations—allowing people to continue producing lactase (the enzyme that breaks down lactose in dairy) well into adulthood, and suggesting that sustained dairy intake actually started leaving a fingerprint on human genetics.

What an amazing journey! But, what can we take away from all of that in terms of establishing whether humans are natural herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores?

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

For one, we can see that meat-eating has been a component of the human diet (and that of our pre-human ancestors) for at least 2.5 million years. And, even before that, it’s likely that our ancestors ate a diet similar to that of modern chimpanzees and other higher primates—which aren’t exactly dripping with steaks and bacon, but definitely aren’t fully herbivorous either (since nonhuman primates love munching on insects and other invertebrates, and some species, like chimps, actually do hunt). We’ll be taking more clues from primate diets and anatomy in the next installment of this series! For now, we can say that humans have never been an herbivorous species, and as best we can tell from existing evidence, neither have the ancestors we descended from.

But, at the same time, we can see that plant foods have also played an important and sustained role throughout our past. The gut shrinkage we saw with Homo erectus limited our ability to derive energy from seriously tough plant matter (like stems and twigs), but we still have colons chock full of bacteria that love fiber and other plant components, and for no extended period in history did we appear to eat animal foods exclusively. A carnivorous past? Not likely! In fact, one theory for the change in brain and gut size we saw with Homo erectus has to do with eating more starchy plant foods, especially in the form of underground storage organs (USOs).

USOs: A Strike Against Carnivory

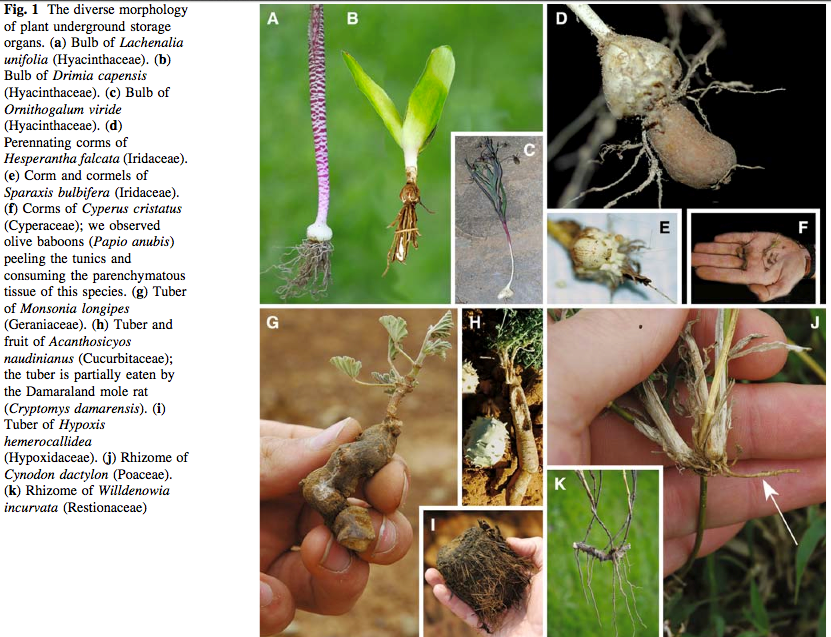

Nope, that’s not a typo for UFOs! Underground storage organs are starchy plant components like bulbs, tubers, rhizomes, and corms. They store water and carbohydrates for the plant to use, but are also a highly nutritious (and energy dense) source of food for humans. We’ve probably been gathering and consuming USOs since long before the dawn of agriculture, and they may have contributed to a significant plant-derived calorie intake even during the Paleolithic era.

Researcher Richard Wrangham is the leading voice for the theory that our crazy big brains and relatively small guts didn’t happen from eating more meat, but from eating more starchy USOs. And, the evidence behind that theory is pretty interesting. Changes in our dental shape coincided with a shift towards using USOs as a fallback food, and the ecology of USOs suggests they would have been plentiful in the environments that early humans inhabited. Homo fossils are often found near shallow-water or flooded habitats (where aquatic USO density is high), and where another brain-growth-spurring treat—aquatic creatures rich in DHA/omega-3 fats—frequently live. Collectively, that evidence suggests that even if animal foods played a significant role in our past, the claim that “meat is what made us human” (and we’re therefore more aligned with carnivores) might not be so accurate!

Of course, until someone invents a time machine and we can peer directly into the distant past, we can’t know exactly what foods early humans ate and what proportions each type of food contributed to their diets. Our best evidence right now is still just an approximation. Luckily, that’s where modern hunter-gatherer and indigenous populations can come to the rescue! Although foods today aren’t necessarily the same ones that were available thousands of years ago, the diet patterns of modern hunter-gatherers can still tell us a lot about human food choices before the influence of agriculture—and help us understand where we fall on the herbivore-omnivore-carnivore spectrum.

Modern Hunter-Gatherers and Indigenous Populations

We’re fortunate to have data for a number of hunter-gatherer and indigenous populations before their diets became Westernized. Here’s a sampling of these diverse communities from around the globe!

- The Hadza of Tanzania: the Hadza are a widely studied hunter-gatherer tribe that consume a variety of tubers, baobab seeds, fruit (especially berries), honey, and meat (mostly large game animals). Their diets are pretty starchy, with over half of their calorie intake coming from carbohydrates. [Photo Credit: Brian M. Wood, Yale University]

- The Masai: the Masai have a reputation for living on nothing but meat, milk, and blood, but this is actually a big misunderstanding. Only one group within the Masai society, young men at the peak of their warrior years (called “moran”), subsist primarily on those foods—and they only spend 15 years of their life that way before resuming a more omnivorous diet. Plus, the moran regularly consume plant foods in the form of herbs and tree barks, which supply health-promoting compounds and micronutrients, and also eat fruit, tubers, and honey when they need extra calories or hydration. Masai women, on the other hand, spend their entire lives eating plenty of plant foods in addition to animal foods and never consume the animal-based moran diet. According to observations from the turn of the last century, the Masai would trade with neighboring societies for plant foods like bananas and sweet potatoes. (Check out this great post by Chris Masterjohn for more information on the Masai diet!)

- The Aché of Paraguay: the Aché hunter-gatherers consume large amounts of meat (over half of their daily calories comes from hunting vertebrate game) but they eat plenty of honey, plants, insects, larvae, palm starch and palm hearts, and fruit when it’s in season.

- The !Kung Bushmen: the !Kung people are known for their incredibly high intake of mongongo nuts and fruit. In fact, the nuts alone make up over half of their entire diet (in terms of calories)! They also eat plenty of baobab seeds, palm tree seeds, wild oranges, plums, mangoes, berries, and a variety of roots. Hunting also plays an important role in their society, and they consume about half a pound of meat per person each day, on average.

- The Inuit: although the Inuit consume large amounts of marine animals and land animals (ranging from seal to fish to caribou), their diets are far from carnivorous! As I explained in my post “The Link Between Meat and Cancer,” the Inuit actually go to great lengths to collect nutrient-dense plant foods that provide a wide spectrum of micronutrients, prebiotics, and probiotics not available from meat and fish (including chlorophyll-rich seaweeds, berries, mosses, wild leafy greens, tubers, and the partially digested stomach contents of animals). They even ferment a number of plant foods as a way of preserving them for year-round use (not to mention, serving as a source of fantastic bacteria for their gut microbiomes!).

Notice any common themes? How about the fact that every single one of these populations eats both plant and animal foods? As far as our evidence dictates, there aren’t any purely herbivorous human societies, and likewise, there aren’t any purely carnivorous ones. Even the populations that could make due with nothing but plant foods (like equatorial tribes) or nothing but animal foods (like arctic tribes) still seek out items from both the plant and animal kingdoms to eat on a regular basis.

And, what’s really notable is that none of these populations get the sorts of diseases and developmental problems we’d expect to see from eating a species-inappropriate diet (such as herbivorous rabbits getting mega cholesterol deposits in their skin and eyes from eating cholesterol-containing foods in scientific studies). It’s not until hunter-gatherer populations start encountering heavily processed modern foods that they end up with degenerative diseases like we see in industrialized nations!

So, what can we conclude from all this? Obviously, humans can survive on a wide range of diets: we’re awesome at making due with whatever the environment gives us and finding a way to subsist on that (or literally die trying!). But, the common denominator in the diets of our ancestors and the diets of modern hunter-gatherers is that contain both plant and animal foods, never exclusively one or the other, nor even dominant one or the other. There’s no evidence that humans, or our genetic ancestors, have ever been purely herbivorous or carnivorous. All signs point to omnivore.

But, there’s still more to the story (and the controversy!). What about human anatomy? What about all those arguments we see regarding our dental structure, digestive tract, stomach acidity, jaw shape, and so forth that seem to prove we’re actually herbivores or carnivores? Stay tuned: we’ll be exploring all that (and more) in the next installment of this series!

Citations

Billings T. “The !Kung San’s main plant foods.” Beyond Vegetarianism. Accessed September 1, 2015.

Braun DR, et al. “Early hominin diet included diverse terrestrial and aquatic animals 1.95 Ma in East Turkana, Kenya.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 Jun 1;107(22):10002-10007.

Cerlin TE, et al. “Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of Turkana Basin hominins.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 Jun 25;110(26):10501-6.

de Heinzelin J, et al. “Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids.” Science. 1999 Apr 23;284(5414):625-9.

Dominy NJ, et al. “Mechanical properties of plant underground storage organs and implications for dietary models of early hominins.” Evolutionary Biology. 2008 May 15;35:159-175.

Ferraro JV, et al. “Earliest Archaeological Evidence of Persistent Hominin Carnivory.” PLoS One. 2013; 8(4): e62174.

Hill K, et al. “Seasonal variance in the diet of Ache hunter-gatherers in Eastern Paraguay.” Human Ecology. June 1984, Volume 12, Issue 2, pp 101-135.

Laden G & Wrangham R. “The rise of the hominids as an adaptive shift in fallback foods: plant underground storage organs (USOs) and australopith origins.” J Hum Evol. 2005 Oct;49(4):482-98.

Luca F, et al. “Evolutionary Adaptations to Dietary Changes.” Annu Rev Nutr. 2010 Aug 21; 30: 291–314.

Masterjohn C. “The Masai Part II: A Glimpse of the Masai Diet at the Turn of the 20th Century — A Land of Milk and Honey, Bananas From Afar.” 13 September 2011.

Perry GH, et al. “Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation.” Nat Genet. 2007 Oct; 39(10): 1256–1260.

Revedin A, et al. “Thirty thousand-year-old evidence of plant food processing.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 Nov 2;107(44):18815-9.

Schnorr SL, et al. “Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers.” Nature Communications. 2014 April 15; Number 5, Article number: 3654

Sponheimer, et al. “Isotopic evidence of early hominin diets.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 Jun 25; 110(26): 10513–10518.

Wrangham R, et al. “Shallow-water habitats as sources of fallback foods for hominins.” Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009 Dec;140(4):630-42.

TPV Podcast, Episode 159, Fermented Cod Liver Oil Debate

TPV Podcast, Episode 159, Fermented Cod Liver Oil Debate