Sleep is one of the most important determinants of our health (see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies! and Natural Approaches to Cold & Flu Season (and Covid-19!)). You’d think that something so essential for our physical and mental wellbeing and that we all enjoy doing (hello sleeping in on the weekend!) would be easier to get! Unfortunately, even when we do make time for a little extra zzzz’s, getting the high quality sleep that we really need can be elusive!

Here are five easy things you can do to improve your sleep immediately. For a more comprehensive resource, be sure to check out Go To Bed: 14 Easy Steps to Healthier Sleep!

1. Sleep and Wake on a Predictable Schedule

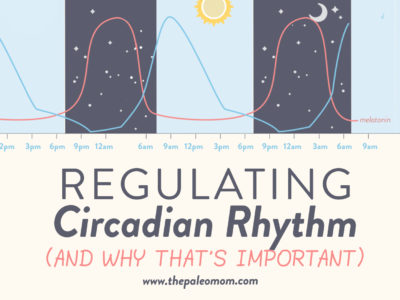

Our bodies have a master clock that controls the ebb and flow of a huge array of biological processes that all cycle according to a 24-hour day. This is called circadian rhythm, and it allows for our bodies to assign functions based on the time of day (and whether or not you are asleep); for example, prioritizing tissue repair while we are sleeping, and prioritizing the search for food, metabolism, and movement while we are awake. The master clock, called the circadian clock, is controlled by specialized cells in a region of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus (SCN). The SCN syncs to the environmental light-dark cycle via specialized ganglion cells in the retina that are directly photosensitive and project to the SCN (via pathway called the retinohypothalamic tract). The master clock then communicates time of day to the rest of the body via two essential circadian rhythm hormones: melatonin, which tells the body that it’s night and time to sleep, and cortisol, which tells the body that it’s morning and time to get up and at ’em. See also Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and why that’s important).

Because our sleep is controlled in large part by melatonin (or directly downstream from melatonin), whose secretion is controlled by the SCN, one of the most important things we can do to promote sleep quality is to sleep on a consistent schedule, i.e., we listen when our master clock tells us it’s bedtime. Sleeping on a consistent schedule helps to entrench our circadian clock, meaning that there isn’t much variability in circadian hormones from one day to the next. Similarly, because our morning spike in cortisol is also controlled by the SCN (of course, cortisol is also the main stress hormone, so our stress levels are an input here as well, see Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What Is Adrenal Fatigue? ), waking on a consistent schedule and getting enough sleep consistently is also important to entrench our circadian clock. The importance of sleeping on a consistent schedule is reflected in obesity and diabetes research that show that variability in sleep timing is a risk factor independent of whether or not we’re getting enough sleep (see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!).

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

2. Love the Sun (or Sun Lamp)!

Most of us are familiar with the fact that our bodies make vitamin D in response to ultraviolet light from the sun (see Why Sun Exposure Is So Important and Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm?). But, when it comes to sleep, there’s another effect of sunlight that is far more important: the bright blue wavelengths of light from the sun are the most potent portion of the visible electromagnetic spectrum for circadian regulation.

Exposure to sunlight during the day helps increase melatonin production in the evening (called dim light melatonin production) which helps prepare our bodies for sleep and ensures adequate restorative deep sleep, especially during the first half of the night. In addition to being critical for quality sleep, melatonin is a powerful antioxidant, is important for intestinal function, and can help prevent depression.

How much time we need to spend outside depends on our personal body chemistry, how much skin is exposed, what time of day it is, what time of year it is, clouds and air quality, and where we live. It’s best to aim for as much as possible (taking care not to get a sunburn!), but at least 20 minutes most days is a good rule of thumb (if you notice that you sleep better with more, make however much that is part of your routine instead). And while we’re stuck inside? Studies show that spending time by a bright window can be helpful.

For shift workers, inhospitable weather, northern climates, long work days, and other barriers to being outside during the day, a great biohack is a light therapy box. Choose one that is at least 10,000 lux; either white or blue light boxes work equally well. Use it (placing it a foot or two away from your face in your peripheral vision) for at least 15 minutes (30+ minutes is better) at roughly the same time every morning or midday (and if you are a shift worker, use the light box during whatever time of day is your morning or midday). A great option is this $20 LED light therapy lamp which you can get on Amazon.

3. Change Up Your Light Exposure in the Evening

Just as it’s important for our bodies to get the signal that it’s daytime during the day (or your day, if you’re a shift worker and using a light therapy box), it’s important to tell our body it’s night time once the sun goes down. Our brains start releasing melatonin about two hours before we normally go to bed, which makes us feel sleepy and lowers our body temperature. But melatonin production can be inhibited by exposure to bright indoor lights in the evenings. This means avoiding blue light (which is very high from LED bulbs and screens) and sticking with red and yellow wavelengths of light as well as keeping the overall light level much (much, much) dimmer.

Probably the best biohack for supporting evening melatonin production (more technically called dim-light melatonin production) is to wear amber-tinted glasses for the last 2-3 hours of the day. In fact, several scientific studies show that these goofy glasses improve sleep quality and melatonin production in a variety of populations and under a variety of conditions (like shiftwork, delayed sleep phase disorder, mania, athletes, and normal healthy people!). What are amber-tinted glasses? Quite simple: glasses with orange (or yellow-orange) lenses! These could be glaucoma glasses or orange safety glasses, but you’ll appreciate investing in more technologically advanced pair of blue-blocking amber glasses since they’re so much more comfortable, can be made with prescription lenses, and because they selectively block the blue light that interferes with melatonin but not other wavelengths making them very clear to see with .

4. Consume Coffee in the Morning ONLY

Caffeine makes us feel more awake and energetic by blocking the sleep signal generated by adenosine, a protein waste product that accumulates over the course of the day. Unfortunately, when we consume caffeine, our levels of the stress hormone cortisol increase (dependent how well we manage stress management and how much caffeine we consume) which can stay elevated for up to 6 hours (see How Stress Undermines Health, How Chronic Stress Leads to Hormone Imbalance, and Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut).

In habitual consumers of caffeine (a huge majority of us!), cortisol increases much more dramatically in response to stress (like that guy cutting you off in traffic) compared to someone who doesn’t consume caffeine. With daily consumption, our bodies can adapt somewhat to not produce quite as much cortisol in response to caffeine, but complete tolerance does not ever occur. If you have difficulty managing stress or falling asleep as it is, caffeine is not your friend.

In addition, recent studies showed that caffeine intake disrupts circadian rhythm by pushing it back (see Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and why that’s important)); so, even if we’re tired and want to go to bed early, consuming caffeine later than noon might make that goal impossible.

5. Eat Starchy Veggies with Dinner

In addition to the other reasons to avoid carb-phobia, there’s evidence that our bodies seem primed for slow-burn starchy carbohydrates in the evening (also see The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body, Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, How Many Carbs Should We Eat? and How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut). We produce more starch-digesting enzymes in the evening, and studies show that eating a decent quantity (say something like 30 grams) starchy carbs from whole food sources at dinner significantly improves sleep!

Fiber intake also improves sleep quality and latency (how long it takes us to fall asleep) in addition to all the other good things fiber does (see The Fiber Manifesto–Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good? and Because Fiber Wasn’t Awesome Enough: New Science Suggests Fiber Improves Sleep Quality!). The great news is that we can kill two birds with one stone with a veggie-rich dinner that includes starchy veggies like sweet potatoes, plantains, cassava, taro, or acorn squash!

The good news is that the quality of our sleep is very responsive to small changes we can make during the day! And these 5 biohacks are a great place to start!*

Want more great tips on improving your sleep? Check out Go To Bed: 14 Easy Steps to Healthier Sleep!

The Go To Bed online sleep program includes: a 350+ page guidebook packed with information and inspiration, plus 14-day sleep challenge, 58-page quickstart guide and a great resource toolkit that includes sleep journal printables, nutrients for sleep printable, and a sleep meditation track!

Citations

Cajochen C, Chellappa S, Schmidt C.What keeps us awake? The role of clocks and hourglasses, light, and melatonin. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2010;93:57-90. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)93003-1.

Dodd FL, Kennedy DO, Riby LM, Haskell-ramsay CF. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of caffeine and L-theanine both alone and in combination on cerebral blood flow, cognition and mood. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015;232(14):2563-76.

Lane JD et al. Caffeine effects on cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to acute psychosocial stress and their relationship to level of habitual caffeine consumption. Psychosomatic Med. 1990; 52(3):320-36.

Lovallo W. et al. Caffeine stimulation of cortisol secretion across the waking hours in relation to caffeine intake levels. Psychosomatic Med. 2005;67:734-739

Lovallo WR et al. Stress-like adrenocorticotropin responses to caffeine in young healthy men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;55:365–9.

Miller B, O’connor H, Orr R, Ruell P, Cheng HL, Chow CM. Combined caffeine and carbohydrate ingestion: effects on nocturnal sleep and exercise performance in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(12):2529-37.

Mccarty DE, Chesson AL, Jain SK, Marino AA. The link between vitamin D metabolism and sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(4):311-9.

Qi Q, Zheng Y, Huang T, et al. Vitamin D metabolism-related genetic variants, dietary protein intake and improvement of insulin resistance in a 2 year weight-loss trial: POUNDS Lost.

Sofer S, Eliraz A, Madar Z, Froy O. Concentrating carbohydrates before sleep improves feeding regulation and metabolic and inflammatory parameters in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;414:29-41.

Miller B, O’connor H, Orr R, Ruell P, Cheng HL, Chow CM. Combined caffeine and carbohydrate ingestion: effects on nocturnal sleep and exercise performance in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(12):2529-37.