Leaky gut is gaining more and more acceptance as something that not only coexists alongside a huge number of health conditions (including autoimmune diseases, food allergies, joint pain, and neurological problems), but that can directly contribute to those very conditions! And, while some medical professionals still scoff at the term “leaky gut,” the more official phrase “increased intestinal permeability” is backed by a huge body of literature as a legitimate player in many diseases.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

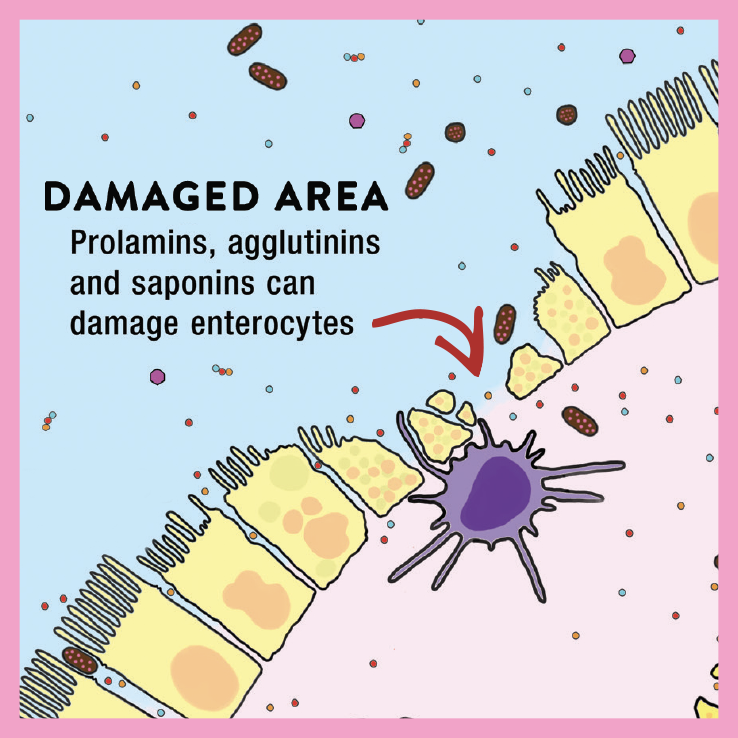

The entire surface of our intestine (called the epithelium) is lined with a single layer of firmly connected cells, which act as a barrier between the outside world (inside our digestive tracts) and our internal environment (inside our bodies). Leaky gut occurs when the tight junctions binding these cells together become “leaky,” allowing protein fragments, bacteria, waste, endotoxins, and other pathogens to pass through. When that happens, the gut’s resident immune cells launch an attack against the foreign invaders, triggering a cascade of reactions that contribute to inflammation and ongoing immune activity. (For more on how leaky gut develops, check out “What Is A Leaky Gut?” and also check out my Leaky Gut Mini-Course)

The entire surface of our intestine (called the epithelium) is lined with a single layer of firmly connected cells, which act as a barrier between the outside world (inside our digestive tracts) and our internal environment (inside our bodies). Leaky gut occurs when the tight junctions binding these cells together become “leaky,” allowing protein fragments, bacteria, waste, endotoxins, and other pathogens to pass through. When that happens, the gut’s resident immune cells launch an attack against the foreign invaders, triggering a cascade of reactions that contribute to inflammation and ongoing immune activity. (For more on how leaky gut develops, check out “What Is A Leaky Gut?” and also check out my Leaky Gut Mini-Course)

Previously, we’ve looked at what foods to avoid if we’re trying to heal leaky gut (most notably foods that irritate the gut or cause the gut junctions to widen, such as gluten-containing grains, high-lectin foods like legumes, dairy, nightshades, and egg whites). We’ve also looked at things that support gut health in a general sense by reducing inflammation (see Why Grains Are Bad, Part 2, Omega 3 vs. 6 Fats), supplying probiotics (see The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods), feeding our gut bacteria (see The Importance of Vegetables and The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?) and providing important amino acids to boost the integrity of the digestive tract (one of the many reasons Why Broth is Awesome!).

These recommendations are all well and good, and they’re still cornerstones for improving gut health. But, are there any specific nutrients that actually tighten up those gut junctions to tackle leaky gut head-on?

Thanks to some recent research, we know the answer is yes!

Nutrients for Leaky Gut

In addition to a variety of studies using supplemental nutrients and botanicals in live animals or humans (typically measuring permeability using , cell culture studies have proven an invaluable tool for understanding the nutrient-permeability link. Using the CACO-2 epithelial cell model (a popular way to study leaky gut, because these cells can be cultured to resemble the enterocytes lining the intestine), researchers have been able to test the effects of different micronutrients and phytochemicals on intestinal permeability. This is done by feeding epithelial cells solutions that contain each nutrient, and then measuring the electrical voltage, current, and resistance across those cells (which gauges how strong the barrier function is) along with testing mannitol flux (the rate off diffusion across the cell layer). Researchers can also measure whether each nutrient affects tight junctional proteins, as well as various genes involved in regulating permeability.

From these kinds of experiments, we’ve learned that certain nutrients can help remodel the tight junctional complex that bind the cells that form the gut lining together, resulting in a structure that’s less leaky. And, each junction-tightening nutrient appears to exert its benefits in a unique way, making all of them important for different reasons!

The nutrients shown to cause beneficial changes in the tight juncture composition are:

Zinc.

Zinc deficiency is known to compromise the integrity of the gut barrier, though for a long time, the mechanisms weren’t clearly understood. Several recent studies have solved the mystery! It turns out that zinc has a targeted effect on tight junction proteins and helps regulate their permeability, and can also offset the effects of agents that impair barrier integrity (such as proinflammatory cytokines). In the CACO-2 cell line, zinc supplementation significantly increases transepithelial electrical resistance (meaning the barrier function is improves).

Zinc deficiency is known to compromise the integrity of the gut barrier, though for a long time, the mechanisms weren’t clearly understood. Several recent studies have solved the mystery! It turns out that zinc has a targeted effect on tight junction proteins and helps regulate their permeability, and can also offset the effects of agents that impair barrier integrity (such as proinflammatory cytokines). In the CACO-2 cell line, zinc supplementation significantly increases transepithelial electrical resistance (meaning the barrier function is improves).

The best sources of zinc? Oysters top the charts (and to a lesser extent, other shellfish), and other rich sources include organ meats (especially liver), red meat, poultry, and pumpkin seeds. See Oysters, Clams, and Mussels, Oh My! Nutrition Powerhouses or Toxic Danger? and 3 Food-Based Supplements for Your Gut Microbiome

Quercetin.

Quercetin is a flavonoid that can cause structural modifications of the tight juncture complex, leading to a more robust gut barrier. In fact, research shows that quercetin can protect against known barrier disruptors like TNF-alpha, indomethacin, and hydrogen peroxide—possibly through the activation of an enzyme called protein kinase C-delta. This makes quercetin a serious boon for anyone trying to fix leaky gut!

Quercetin is a flavonoid that can cause structural modifications of the tight juncture complex, leading to a more robust gut barrier. In fact, research shows that quercetin can protect against known barrier disruptors like TNF-alpha, indomethacin, and hydrogen peroxide—possibly through the activation of an enzyme called protein kinase C-delta. This makes quercetin a serious boon for anyone trying to fix leaky gut!

Luckily, quercetin is easy to come by in a variety of plant foods, especially onions, apples, and citrus fruits. Other sources include black and green tea, tomatoes, cruciferous veggies, dark berries, cherries, and some herbs (such as sage).

Butyrate.

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that certain gut microbes can produce from fiber (it’s also found in certain foods, most notably butter). Among its many benefits for our health, butyrate enhances intestinal barrier integrity and helps combat leaky gut. In studies, butyrate consistently increases transepithelial resistance and reduces mannitol flux (indicating a more robust barrier). The mechanism? Butyrate works by upregulating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, which in turn accelerates the assembly of tight junctions. So, along with offering well-established protection against colorectal cancer (along with an impressive list of other health perks), butyrate is a major player in tightening up a leaky gut.

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that certain gut microbes can produce from fiber (it’s also found in certain foods, most notably butter). Among its many benefits for our health, butyrate enhances intestinal barrier integrity and helps combat leaky gut. In studies, butyrate consistently increases transepithelial resistance and reduces mannitol flux (indicating a more robust barrier). The mechanism? Butyrate works by upregulating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, which in turn accelerates the assembly of tight junctions. So, along with offering well-established protection against colorectal cancer (along with an impressive list of other health perks), butyrate is a major player in tightening up a leaky gut.

So, where do we get butyrate? Most of the studies showing a benefit of butyrate on intestinal permeability are using microbial butyrate, the kind produced from fiber. Bacterially derived butyrate may be more potent than butyrate that comes directly from food (due to fiber feeding and supporting the gut microbiome), so the best bet is to chow down on fiber, and plenty of it! That means leafy greens, other vegetables (including sea vegetables and fermented veggies), tubers, fruit, and nuts and seeds if they’re tolerated. (Considering all the other benefits nutrient-dense plant foods have to offer, eating abundantly from the plant kingdom should be a no-brainer! See The Importance of Vegetables)

Curcumin.

Curcumin, the bright yellow chemical that gives turmeric its vivid color, can help restore the gut’s epithelial structure and reduce intestinal permeability, especially after intestinal injury. Some studies suggest it can counteract changes in the barrier function induced by a Standard Western Diet. Also see Turmeric: The Full Scoop.

Curcumin, the bright yellow chemical that gives turmeric its vivid color, can help restore the gut’s epithelial structure and reduce intestinal permeability, especially after intestinal injury. Some studies suggest it can counteract changes in the barrier function induced by a Standard Western Diet. Also see Turmeric: The Full Scoop.

The best source of curcumin is turmeric, as well as turmeric-containing spice mixes like homemade curry powder (studies of commercial curry powders show they have relatively low levels of curcumin, so making your own and including plenty of turmeric is a good way to go!).

Indole.

Indole (a heterocyclic aromatic compound) helps fight leaky gut by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which can harm the integrity of the gut barrier, and by increasing the expression of genes that help produce mucin and strengthen the mucosal barrier. Studies also show that indole increases transepithelial electrical resistance (AKA, boosting barrier integrity).

Indole (a heterocyclic aromatic compound) helps fight leaky gut by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, which can harm the integrity of the gut barrier, and by increasing the expression of genes that help produce mucin and strengthen the mucosal barrier. Studies also show that indole increases transepithelial electrical resistance (AKA, boosting barrier integrity).

Where can we find indole? The best sources include cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, collard greens, mustard greens, kale, turnips, rutabegas, and Brussels sprouts (in general, crucifers are high in indoles!). Indole can also be converted by gut bacteria from the amino acid tryptophan, which is found in most protein-based foods like meat, fish, eggs, poultry, and some seeds (especially sunflower seeds and pumpkin seeds).

Berberine.

Berberine is a plant-derived alkaloid commonly used to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce blood sugar, but it turns out, it can also significantly improve tight junction permeability! Research on Berberine shows it can both increase electrical resistance and reduce flux rate, and that it’s effective in repairing damaged intestinal mucosa and restoring intestinal permeability. In fact, the anti-hyperglycemic effects of Berberine may be due to the way this alkaloid changes intestinal function.

Berberine is a plant-derived alkaloid commonly used to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce blood sugar, but it turns out, it can also significantly improve tight junction permeability! Research on Berberine shows it can both increase electrical resistance and reduce flux rate, and that it’s effective in repairing damaged intestinal mucosa and restoring intestinal permeability. In fact, the anti-hyperglycemic effects of Berberine may be due to the way this alkaloid changes intestinal function.

As far as dietary sources go, Berberine is most abundant in certain plants and herbs, including goldenseal, goldthread, Oregon grape, tree turmeric, European barberry, yellowroot, and California poppy. True, most of those aren’t easy to find in the grocery store; fortunately, high-quality supplements are available.

L-Glutamine

The amino acid glutamine is currently the best-known compound for reducing intestinal permeability. In fact, a leaky gut can be caused by glutamine deficiency. Glutamine is actually the preferred fuel source for both enterocytes and the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Glutamine deficiency may be a direct result of the increased utilization of glutamine by the overactive immune system in autoimmune disease, thereby propagating a leaky gut. Glutamine works in concert with other amino acids, such as leucine and arginine, to maintain gut integrity and gut-barrier function. It is also essential for proper immune function. Glutamine supplementation has been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory bowel diseases as well as a variety of other conditions affecting the integrity of the gut. (Dosage ranges from 0.3 to 0.5 grams per kilogram of body weight, which means approximately 10–40 grams per day.) Because glutamine is a fuel source for all epithelial cells, it may also be helpful in autoimmune diseases affecting other epithelial-cell barriers, such as the skin and lungs. You can buy L-glutamine in powdered form, which mixes easily with water. Amino acid supplements are generally best absorbed when taken on an empty stomach. Glutamine can also be naturally found in bone broth and meat (see Broth: Hidden Dangers in a Healing Food? and The Role of Glutamine in Gut Health).

The amino acid glutamine is currently the best-known compound for reducing intestinal permeability. In fact, a leaky gut can be caused by glutamine deficiency. Glutamine is actually the preferred fuel source for both enterocytes and the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Glutamine deficiency may be a direct result of the increased utilization of glutamine by the overactive immune system in autoimmune disease, thereby propagating a leaky gut. Glutamine works in concert with other amino acids, such as leucine and arginine, to maintain gut integrity and gut-barrier function. It is also essential for proper immune function. Glutamine supplementation has been shown to benefit patients with inflammatory bowel diseases as well as a variety of other conditions affecting the integrity of the gut. (Dosage ranges from 0.3 to 0.5 grams per kilogram of body weight, which means approximately 10–40 grams per day.) Because glutamine is a fuel source for all epithelial cells, it may also be helpful in autoimmune diseases affecting other epithelial-cell barriers, such as the skin and lungs. You can buy L-glutamine in powdered form, which mixes easily with water. Amino acid supplements are generally best absorbed when taken on an empty stomach. Glutamine can also be naturally found in bone broth and meat (see Broth: Hidden Dangers in a Healing Food? and The Role of Glutamine in Gut Health).

DGL

A variety of mucilaginous plants—including licorice root, slippery elm, marshmallow root, and aloe—are noted for their ability to help repair the gut barrier because they thicken the gut’s mucus layer. But since they may be immune stimulators, they should be avoided in the presence of autoimmune disease. Licorice root, slippery elm, and aloe all have immune-stimulating properties. Aloe has been shown to dramatically increase cytokine production, especially cytokines that stimulate Th2 cells. Licorice root (or an extracted compound from licorice root called glycyrrhizin) enhances the secretion of cytokines by macrophages known to stimulate Th1 cells. Fortunately, there is a supplement called deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL), in which the immune-stimulating glycyrrhizin has been removed, and this may be a good option for supporting the repair of the gut barrier. If you take DGL, look for a capsule form, since chewables and lozenges tend to have undesirable other ingredients, like sugar alcohols (see Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners).

A variety of mucilaginous plants—including licorice root, slippery elm, marshmallow root, and aloe—are noted for their ability to help repair the gut barrier because they thicken the gut’s mucus layer. But since they may be immune stimulators, they should be avoided in the presence of autoimmune disease. Licorice root, slippery elm, and aloe all have immune-stimulating properties. Aloe has been shown to dramatically increase cytokine production, especially cytokines that stimulate Th2 cells. Licorice root (or an extracted compound from licorice root called glycyrrhizin) enhances the secretion of cytokines by macrophages known to stimulate Th1 cells. Fortunately, there is a supplement called deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL), in which the immune-stimulating glycyrrhizin has been removed, and this may be a good option for supporting the repair of the gut barrier. If you take DGL, look for a capsule form, since chewables and lozenges tend to have undesirable other ingredients, like sugar alcohols (see Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners).

—

Another supplement often recommended for improving gut-barrier integrity is bovine colostrum. However, it is not clear whether this is beneficial or may even make a leaky gut worse. For example, bovine colostrum reduces the intestinal permeability caused by NSAIDs. but significantly increases intestinal permeability caused by endurance exercise (see Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut ).

Fixing a Leaky Gut

So, the takeaways for us? Considering how instrumental leaky gut may be in a number of health problems, keeping our guts in good shape should be high up on our list of goals. And that includes more than just focusing on the gut microbiome (which is getting plenty of well-deserved attention these days!). Eating a diet that supports intestinal barrier integrity is also imperative, and—lucky for us—is totally feasible with a nutrient-dense Paleo diet high in phytochemicals, vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids, healthy fats, and fiber.

So, the takeaways for us? Considering how instrumental leaky gut may be in a number of health problems, keeping our guts in good shape should be high up on our list of goals. And that includes more than just focusing on the gut microbiome (which is getting plenty of well-deserved attention these days!). Eating a diet that supports intestinal barrier integrity is also imperative, and—lucky for us—is totally feasible with a nutrient-dense Paleo diet high in phytochemicals, vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids, healthy fats, and fiber.

Want to learn even more about restoring gut health? Check out my Gut Health Fundamentals online course.

Citations

Amirghofran, Z., Herbal medicines for immunosuppression, Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;11(2):111-9

Bansai T, et al. “The bacterial signal indole increases epithelial-cell tight-junction resistance and attenuates indicators of inflammation.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 5;107(1):228-33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906112107. Epub 2009 Dec 4.

Buckley, J.D., et al., Bovine colostrum supplementation during running training increases intestinal permeability, Nutrients. 2009;1(2):224-34

Calder, P.C. and Yaqoob, P., Glutamine and the immune system, Amino Acids. 1999;17(3):227-41

Canani RB, et al. “Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extra intestinal diseases.” World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Mar 28; 17(12): 1519–1528.

Dai, J.H., et al., Glycyrrhizin enhances interleukin-12 production in peritoneal macrophages, Immunology. 2001;103(2):235-43

Deters, A., et al., Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from Marshmallow roots (Althea officinalis L.): cellular internalisation and stimulation of cell physiology of human epithelial cells in vitro, J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127(1):62-9

D’Souza, R. and Powell-Tuck, J., Glutamine supplements in the critically ill, J R Soc Med. 2004;97(9):425-427

Ghosh SS, et al. “Oral supplementation with non-absorbable antibiotics or curcumin attenuates western diet-induced atherosclerosis and glucose intolerance in LDLR-/- mice–role of intestinal permeability and macrophage activation.” PLoS One. 2014 Sep 24;9(9):e108577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108577. eCollection 2014.

Halder, S., et al., Augmented humoral immune response and decreased cell-mediated immunity by Aloe vera in rats, Inflammopharmacology. 2012;20(6):343-6

Li, J., et al., Immunosuppressive activity on the murine immune responses of glycyrol from Glycyrrhiza uralensis via inhibition of calcineurin activity, Pharm Biol. 2010;48(10):1177-84

Mariadason JM, et al. “Effect of short-chain fatty acids on paracellular permeability in Caco-2 intestinal epithelium model.” Am J Physiol. 1997 Apr;272(4 Pt 1):G705-12.

Mercado J, et al. “Enhancement of tight junctional barrier function by micronutrients: compound-specific effects on permeability and claudin composition.” PLoS One. 2013 Nov 13;8(11):e78775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078775. eCollection 2013.

Peng L, et al. “Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers.” J Nutr. 2009 Sep;139(9):1619-25. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104638. Epub 2009 Jul 22.

Plöger S, et al. “Microbial butyrate and its role for barrier function in the gastrointestinal tract.” Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012 Jul;1258:52-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06553.x.

Rapin, J.R. and Wiernsperger, N., Possible Links between Intestinal Permeablity and Food Processing: A Potential Therapeutic Niche for Glutamine, Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65(6):635-643

Rees WD, et al. Effect of deglycyrrhizinated liquorice on gastric mucosal damage by aspirin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1979;14(5):605-7.

Shan CY, et al. “Alteration of the intestinal barrier and GLP2 secretion in Berberine-treated type 2 diabetic rats.” J Endocrinol. 2013 Jul 29;218(3):255-62. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0184. Print 2013 Sep.

Sturniolo GC, et al. “Effect of zinc supplementation on intestinal permeability in experimental colitis.” J Lab Clin Med. 2002 May;139(5):311-5.

Sturniolo GC, et al. “Zinc supplementation tightens “leaky gut” in Crohn’s disease.” Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001 May;7(2):94-8.

Tian S, et al. “Curcumin protects against the intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury: involvement of the tight junction protein ZO-1 and TNF-α related mechanism.” Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016 Mar; 20(2): 147–152.

Valentano MC, et al. “Remodeling of Tight Junctions and Enhancement of Barrier Integrity of the CACO-2 Intestinal Epithelial Cell Layer by Micronutrients.” PLoS One. 2015 Jul 30;10(7):e0133926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133926. eCollection 2015.

Wang X, et al. “Zinc supplementation modifies tight junctions and alters barrier function of CACO-2 human intestinal epithelial layers.” Dig Dis Sci. 2013 Jan;58(1):77-87. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2328-8. Epub 2012 Aug 19.