Adrenal fatigue is a consequence of chronic stress, caused by inadequate function of adrenal glands, and characterized by a collection of symptoms, which can include: fatigue, poor sleep or insomnia, mood swings, unexplained weight gain or loss, inflammation, high cardiovascular disease risk factors, insulin resistance, decreased sex drive, joint pain, and frequent infections like colds and flu.

Diagnosis rates are increasing dramatically within the alternative health communities, yet there is still a great deal of misinformation out there regarding adrenal fatigue. There is a tendency for many to self diagnose based on symptoms (and self-medicate using various adaptogen cocktails available at health food stores, supplement stores and online). Worse, there are some practitioners who are diagnosing adrenal fatigue based on questionnaires and symptom checklists only. I can not emphasize enough that this is a medical condition that requires detailed testing in order to individualize treatment protocols successfully.

This is the first post in a 3-part series discussing adrenal fatigue in detail. Here, I’m going to detail exactly what adrenal fatigue is and the symptoms it causes at various phases. In Part 2, I’ll discuss diagnostic options as well as differential diagnostics; and in Part 3, I’ll talk about recovery from adrenal fatigue.

An important disclaimer: it’s worthwhile to note that adrenal fatigue is not recognized by many conventional medical practitioners (unless you’ve pushed your adrenals to the level of chronic adrenal insufficiency or suffer from Addison’s disease). However, when we pull together the clinical evidence, some concepts from evolutionary biology, and recent developments in laboratory testing, it is easy to see that many people’s adrenal glands (mine included, see My Personal Battles with Stress and TPV Podcast, Episode 136: Adrenal Fatigue) are challenged to accommodate the stress demands that we have put on them as a society and individually. If your primary care physician is not engaging in a conversation regarding a possible adrenal fatigue diagnosis, you might consider finding a functional or integrative medicine specialist or use the services from ThePaleoMom Consulting.

An important disclaimer: it’s worthwhile to note that adrenal fatigue is not recognized by many conventional medical practitioners (unless you’ve pushed your adrenals to the level of chronic adrenal insufficiency or suffer from Addison’s disease). However, when we pull together the clinical evidence, some concepts from evolutionary biology, and recent developments in laboratory testing, it is easy to see that many people’s adrenal glands (mine included, see My Personal Battles with Stress and TPV Podcast, Episode 136: Adrenal Fatigue) are challenged to accommodate the stress demands that we have put on them as a society and individually. If your primary care physician is not engaging in a conversation regarding a possible adrenal fatigue diagnosis, you might consider finding a functional or integrative medicine specialist or use the services from ThePaleoMom Consulting.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

The Adrenal Glands and Steroid Hormones

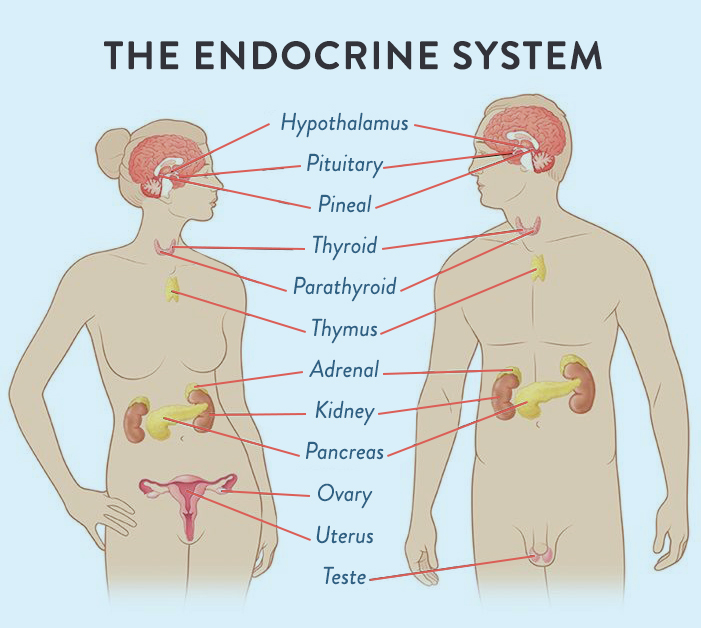

The adrenal glands are small, triangle-shaped glands located on top of the kidneys in the abdominal cavity. These glands are the major site of steroid hormone production and coordination; they are a very significant component of the human endocrine (hormone) system, so when they’re out of whack, a lot of processes (e.g., blood sugar regulation) can go awry. This fact is highlighted by the incredible breadth of functions that corticoid hormones have. Oh, and for the record: when I use the term “steroid” here–often used interchangeably (and erroneously) with the class of drugs used to dampen the immune system and the anabolics used by bodybuilders–I’m referring to a specific chemical structure that involves multiple (generally, four) carbon rings and a chain of carbons at the terminal end; this structure is common both in hormones and in membrane components.

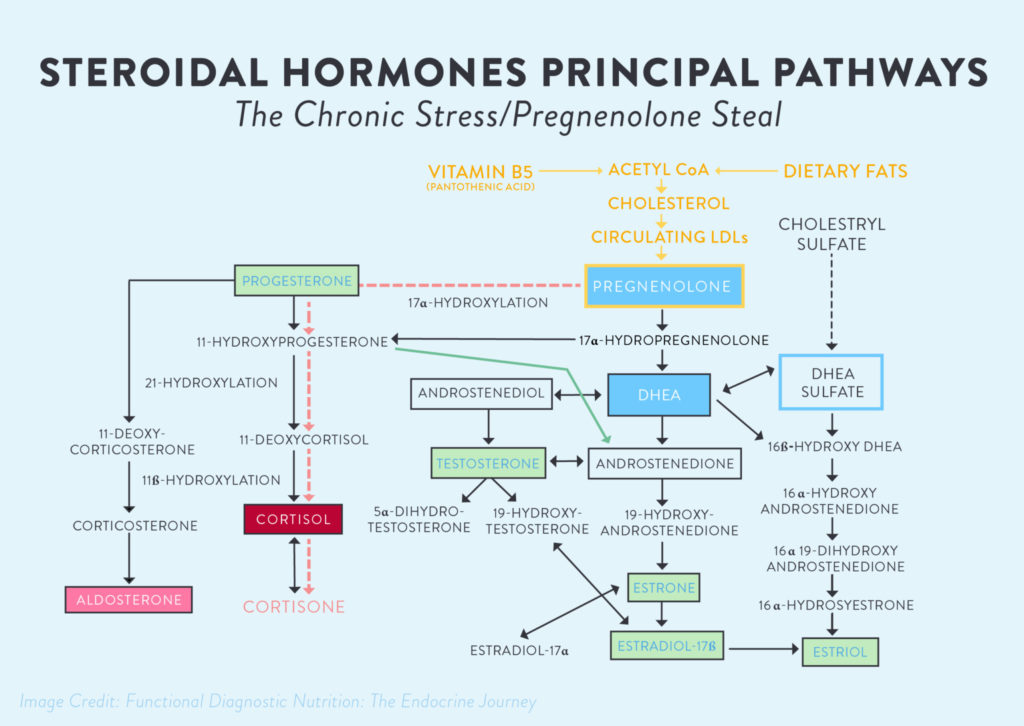

The steroid hormones include mineralcorticoids, glucocorticoids, and androgens. Mineralcorticoids (like aldosterone) influence salt and water balance; these act mainly at the kidneys to regulate how much we retain versus excrete. Glucocorticoids regulate the immune system by reducing its activity; this includes up-regulating the amount of anti-inflammatory proteins and down-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory proteins in response to both acute situations (like a cold) and the general day-to-day function that the immune system manages. The most important human glucocorticoid is cortisol (amazing that it’s actually anti-inflammatory, right?).

Androgens are the sex hormones, which we know influence both primary and secondary sex characteristics, including sexual behavior and adiposity (especially in women). These signaling molecules, especially intermediates, are mostly created in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum of cells in the adrenal glands, but a couple (including aldosterone and cortisol) are made in the mitochondria. And all of them have one common precursor: cholesterol.

Cholesterol is that infamous molecule that many of us in the Paleo community have fought to bring back into the diets of everyone everywhere because of its huge significance in the human body. A large part of that reason, apart from it being a fundamental part of every single cellular membrane in our bodies, is that it is an incredibly important hormone precursor, meaning that it is the first molecule in a chain of reactions that produce the many steroid hormones. When we don’t eat cholesterol, it must be synthesized by the liver, which is a significant metabolic burden; so, yes, you don’t need to limit dietary cholesterol! Before all of the steroid hormones can be made, cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone. Pregnenolone is then shuttled to one of three pathways (mineralcorticoids, glucocortisoids, and androgens) according to the body’s most urgent need(s).

Long story short, all of these hormones are major components of two axes that ultimately communicate with the brain and result in big changes in our health and behavior: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal (HPG) axis.

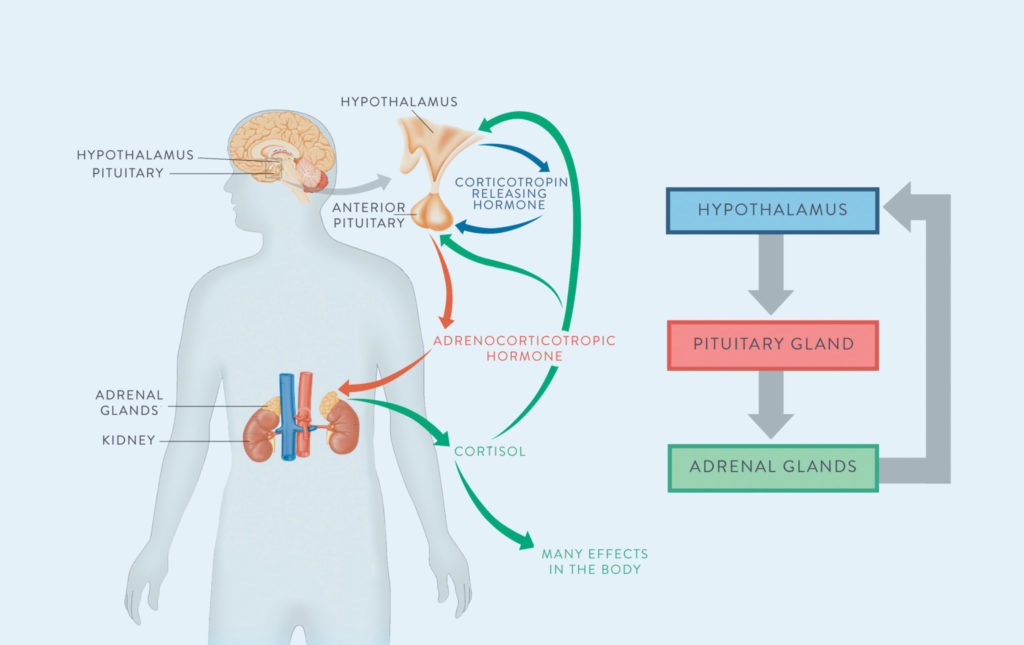

The HPA Axis

The HPA Axis is responsible for the flight-or-fight response. The hypothalamus (which receives signals from the hippocampus, the region of the brain that amalgamates information from all the senses and can thus perceive danger and make decisions) releases a hormone called Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to release a hormone called Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH), which signals to the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol as well as catecholamines (like adrenaline).

Cortisol is the most significant, commonly-released glucocorticoid in the body. Almost every cell in our bodies have glucocorticoid receptors – so this little molecule can act throughout our entire body! Cortisol has an amazing range of effects in the body, including controlling metabolism, affecting insulin sensitivity, affecting the immune system, and even controlling blood flow. If you’re running away from a lion, all these effects (plus the combined effects of catecholamines and some direct effects of CRH) combine to prioritize the most essential functions for survival (perception, decision making, energy for your muscles so you can run away or fight for your life, and preparation for wound healing) and inhibit non-essential functions (like some aspects of the immune system especially not in the skin, digestion, kidney function, reproductive functions, growth, collagen formation, amino acid uptake by muscle, protein synthesis and bone formation).

Cortisol also provides negative feedback to the pituitary and the hypothalamus. It’s the body’s way of saying, “hey, we got the signal that we’re supposed to be stressed now, thanks, we’re on it!” If the stressful event has ceased (the lion gave up and left), this is what deactivates the HPA axis. Of course, if a stressor is still being perceived (that lion is still there), the HPA axis remains activated. And this is why chronic stress (deadlines, traffic, sleep deprivation, teenagers, divorce, being sick, being inflamed, alarm clocks, bills, and internet trolls) is such a problem: the net effect of cortisol is catabolic, meaning that it prepares the body for action without giving it any opportunity to rebuild! And, as we know, chronic stress can be incredibly long term… like decades. So, the amount of pressure that puts on the adrenal glands to produce cortisol in order to combat our perceived stressors is magnanimous – and that’s where adrenal fatigue comes into play.

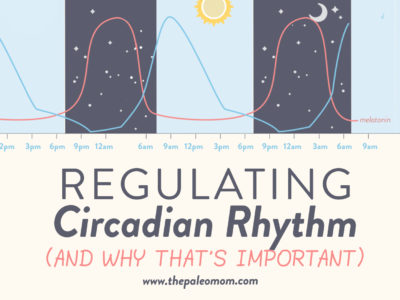

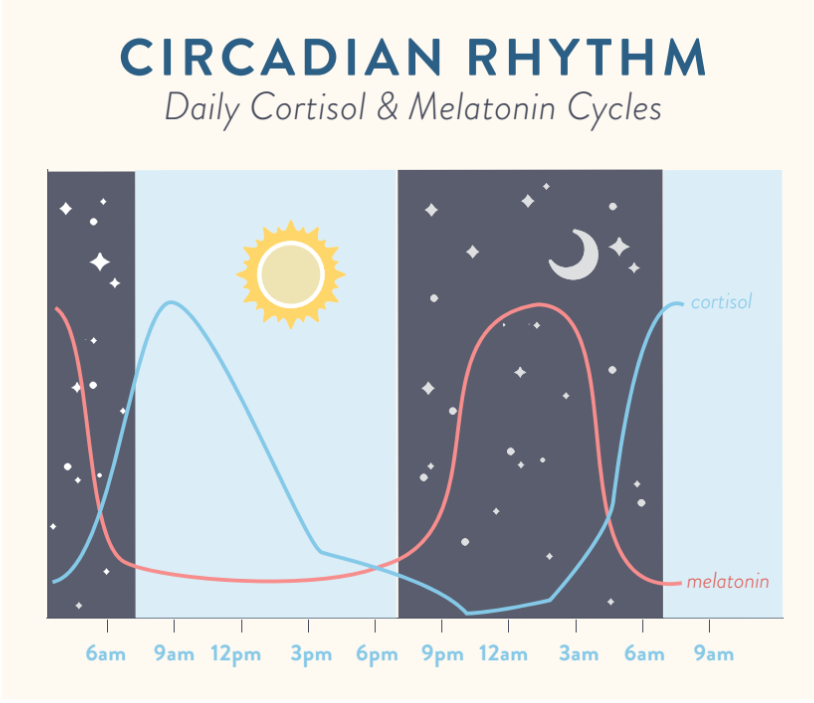

However, I don’t want to paint the picture that cortisol is some evil molecule out to undermine us at all – it isn’t! Having regulated amounts of cortisol circulating is essential for life, because it prevents us from going dangerously hypoglycemic (recall that cortisol promotes gluconeogenesis, the process of new glucose formation in the liver). Cortisol in appropriate doses also acts an anti-inflammatory molecule that suppresses the immune system; so, if perhaps you got scratched by the tiger before it ran away, cortisol would aid in reducing your pain but delay your healing a bit. This logic is actually the reasoning behind prednisone, a glucocorticoid steroid pharmaceutical, used for pain and immune system suppression (it also explains why these steroids can wreak havoc on the immune system overall). In fact, cortisol is hardly an acute-stress-only (i.e., the lion) hormone: cortisol is released in varying amounts every day. As I write in my online sleep program Go to Bed, this hormone acts in conjunction with melatonin to regulate our sleep-wake cycles. But, it is really important that cortisol fluctuate throughout the day and eventually decline (so that we can indeed go to bed!). Keep this figure in mind as we discuss adrenal fatigue and chronic stress in just a moment (See also Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and why that’s important)).

However, I don’t want to paint the picture that cortisol is some evil molecule out to undermine us at all – it isn’t! Having regulated amounts of cortisol circulating is essential for life, because it prevents us from going dangerously hypoglycemic (recall that cortisol promotes gluconeogenesis, the process of new glucose formation in the liver). Cortisol in appropriate doses also acts an anti-inflammatory molecule that suppresses the immune system; so, if perhaps you got scratched by the tiger before it ran away, cortisol would aid in reducing your pain but delay your healing a bit. This logic is actually the reasoning behind prednisone, a glucocorticoid steroid pharmaceutical, used for pain and immune system suppression (it also explains why these steroids can wreak havoc on the immune system overall). In fact, cortisol is hardly an acute-stress-only (i.e., the lion) hormone: cortisol is released in varying amounts every day. As I write in my online sleep program Go to Bed, this hormone acts in conjunction with melatonin to regulate our sleep-wake cycles. But, it is really important that cortisol fluctuate throughout the day and eventually decline (so that we can indeed go to bed!). Keep this figure in mind as we discuss adrenal fatigue and chronic stress in just a moment (See also Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and why that’s important)).

The HPG Axis

The HPA axis is hardly the only neuroendocrine pathway that our body coordinates to promote health and wellbeing. We also have the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The primary role of the HPG axis is to control reproduction, but it is also important for development (puberty and aging) and the immune system. The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to secrete two hormones: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH and FSH signal to the gonads to produce estrogen and progesterone in women and testosterone in men. I know you’re thinking, “but what does this have to do with my adrenals and why I’m so tired all the darn time?!” I’m getting there, I promise. You see, the thing is that the HPA and HPG axes are not isolated endocrine systems. There’s crosstalk, which makes everything much more complicated (see also How Chronic Stress Leads to Hormone Imbalance).

The HPA axis is hardly the only neuroendocrine pathway that our body coordinates to promote health and wellbeing. We also have the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The primary role of the HPG axis is to control reproduction, but it is also important for development (puberty and aging) and the immune system. The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which signals to the pituitary gland to secrete two hormones: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH and FSH signal to the gonads to produce estrogen and progesterone in women and testosterone in men. I know you’re thinking, “but what does this have to do with my adrenals and why I’m so tired all the darn time?!” I’m getting there, I promise. You see, the thing is that the HPA and HPG axes are not isolated endocrine systems. There’s crosstalk, which makes everything much more complicated (see also How Chronic Stress Leads to Hormone Imbalance).

For instance, progesterone, which is produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, activates the HPA axis. In women, the purpose of progesterone is to prepare the body for pregnancy (for menstruating women, it is higher in the second half of our cycle; when a woman isn’t pregnant, it is the drop in progesterone that triggers menses). The relationship between progesterone and the HPA axis is likely responsible for metabolic shifts, immune system changes, and differences in resource priorities during pregnancy. And considering that progesterone: ever wonder why we crave certain highly palatable foods right before our periods? We can blame the lack of progesterone!

But the links are more insidious than food cravings. Cortisol inhibits the HPG axis at every point. It reduces the production of GnRH by the hypothalamus. It reduces the production of FSH and LH by the pituitary gland. It suppresses ovary function, reducing estrogen and (in part) progesterone secretion. Think about it: if you are running away from a lion, reproduction is just not a priority. The body needs those resources for immediate use. And if we’re running away from lions regularly, our body would want to put off reproduction until the tribe has moved to a safer location (or, say, that work project is completed… or the kids have gone back to school).

There’s yet another complication to this relationship. Remember when I brought up that the there is one universal precursor to all of these hormones? Yep, it’s cholesterol, which is converted to the “mother hormone:” pregnenolone. So, what if the lion never stops chasing you? When we’re chronically stressed, especially when that chronic stress stays high for a long period of time (say, you’re writing a book… Or work in the sciences… Just saying – I am so aware of how much this has affected my life!), it’s essentially the same physiological effect of running away from a lion indefinitely. Not to mention that chronic stress is also associated with a boatload of other incredibly damaging cofactors, like not getting enough sleep, not moving enough, and making poor dietary choices. At some point, our hypothalamus perceives SO much stress, leading to SO much DHEA being released from the pituitary, leading to SO much cortisol in our systems, that the adrenal glands literally start to steal the pregnenolone that was metabolically designated to make our sex hormones. This phenomenon is literally called the “pregnenolone steal.” Not very creative, I know, but at least it’s easier to remember that way.

So, if you’re chronically stressed, estrogen and progesterone can be decreased. And yes, this is an explanation for a multitude of conditions, including amenorrhea (not having a period).

Perhaps unsurprising, but this is also how chronic stress leads to low testosterone in men (one of the symptoms of which can be balding!).

Conversely, when DHEA is low, the body tends to convert testosterone and what little DHEA is being produced into estrogen. Environmental estrogens (like the phytoestrogens in soy or flax seed or walnuts, or like the xenoestrogens in some plastics) further increase estrogen. As many women know, estrogen dominance can be a tricky endocrine problem to conquer as well. Nutrient deficiencies and lifestyle factors like type and frequency of activity can further influence exactly what hormones are getting produced and what hormones aren’t. It’s all very complicated, but, in the end, it is these intricacies that lead to the adrenal fatigue, so knowing the details will help us as we add in the signs and symptoms of this hormone disorder.

So, What Goes Wrong? The Basics of Adrenal Fatigue

Okay, so we’ve gone through the details about the different steroid hormones, the importance of the adrenal glands, and the HPA and HPG axes (and where they – very critically—intersect). And you’re probably ready for me to get to the point: adrenal fatigue.

The very minimalistic view of adrenal fatigue is that it’s the result of serious chronic stress, which we are not evolutionarily equipped to handle. Chronic stress results in elevated serum cortisol all the time, which has a series of associated complications, including:

- Breakdown of muscle

- Excessive adrenaline release

- Hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar)

- Weakened bones

- Worsened immune system function and responsiveness

- Inhibition of reproductive function

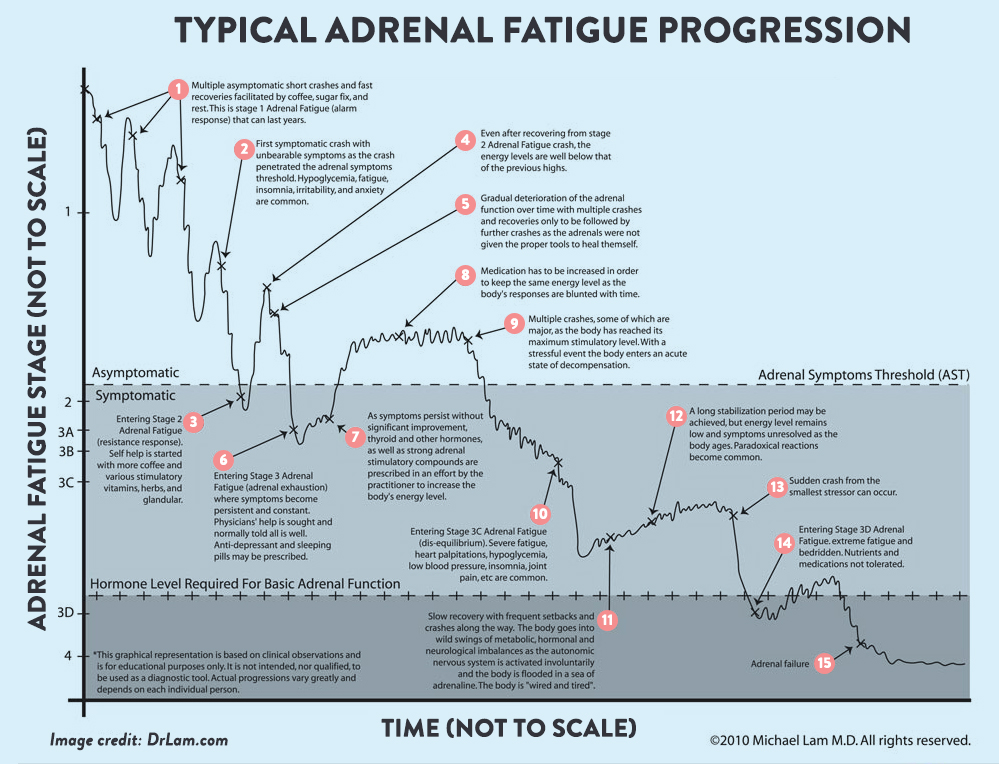

Adrenal fatigue happens when chronic stress continues without relief (and relief means more than just a weekend getaway or an occasional day off – I’m talking about actual stress management on the daily), and the adrenal glands stop being able to function properly. In the naturopathic medical community, adrenal fatigue was originally referred to as the general adaptation symptom – like your adrenals are literally adapting to too much stress! (And a reminder that someone in the conventional medical community is not likely to recognize adrenal fatigue. You’re more likely to get help from an integrative or functional medicine specialist or a licensed naturopathic physician). There are three phases to adrenal fatigue that, in some ways, mimic the release of the hormone cortisol itself. It’s important to emphasize that this disorder occurs after a long period of chronic stress, and there is tons of bioindividuality here.

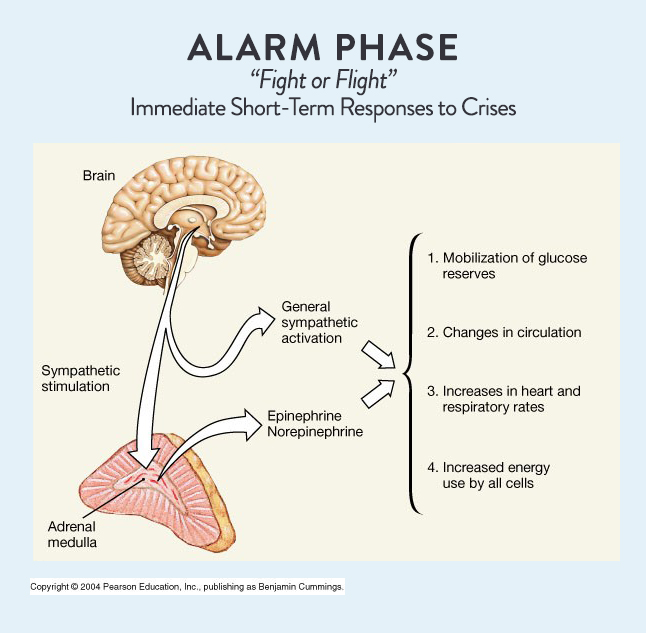

Phase One: Alarm Phase

Phase One of adrenal fatigue is often called the Alarm Phase, because this involves the fight or flight response that we discussed earlier. The alarm phase is a common phenomenon for those of us who’ve dealt with a lot of stress (basically everyone in the modern era). In this phase, we see the normal physiological response from cortisol but in larger amounts than “normal:”

- Blood sugar is elevated

- Blood pressure is elevated

- Heart rate and respiratory rate increase

- Metabolism speeds up at the cellular level

All of these reactions are within normal limits, and, after the stressor is removed, the body is able to recover normally. Importantly, most people in the modern era will dip into and out of this phase as we go through the normal stressors of modern life, like schooling or parenting. Because of how normal it feels, we can be in and out of this phase for years. However, towards the end of this phase, other hormone levels (like DHEA, which we covered as the sex hormone precursor) might start to decrease as the pregnenolone steal starts to occur – but from there, we’re on our way to phase two as our bodies stop being able to bounce back from frequent asymptomatic (normal-feeling) mini-crashes.

In all likelihood, someone will have their first symptomatic crash within Phase One. Here are the common symptoms of a symptomatic crash during Phase One:

In all likelihood, someone will have their first symptomatic crash within Phase One. Here are the common symptoms of a symptomatic crash during Phase One:

- Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar, which could manifest as feeling lightheaded or “hangry”)

- Fatigue

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Anxiety

These symptoms may reflect previous stressful experiences but be exaggerated or feel uncontrollable compared to other crashes. Once someone experiencing a significant crash such as this, they may be on their way to Phase Two.

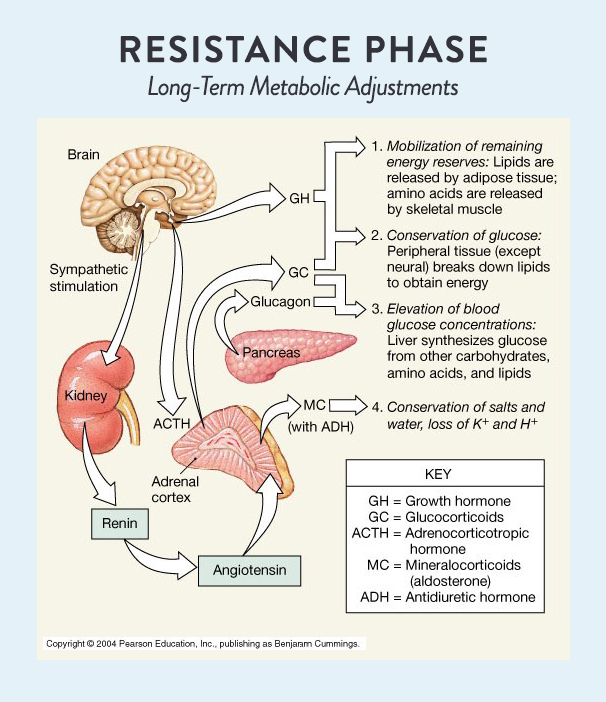

Phase Two: Resistance Phase

Phase Two of adrenal fatigue is referred to as the Resistance Phase. This phase begins when the focus shifts significantly from producing a balance of hormones to producing as much cortisol as possible. This phase is referred to as the resistance phase, because the body has built up a tolerance for cortisol and has functionally adapted to the chronic stress lifestyle. The great irony here is that someone in stage two adrenal fatigue might actually feel great; a lot of people describe this phase as feeling “wired” or “tired and wired.”

Phase Two of adrenal fatigue is referred to as the Resistance Phase. This phase begins when the focus shifts significantly from producing a balance of hormones to producing as much cortisol as possible. This phase is referred to as the resistance phase, because the body has built up a tolerance for cortisol and has functionally adapted to the chronic stress lifestyle. The great irony here is that someone in stage two adrenal fatigue might actually feel great; a lot of people describe this phase as feeling “wired” or “tired and wired.”

Pregnenolone steal is in full force here, and people will experience reduced sex hormones (this might manifest itself as fewer gains in the gym due to less testosterone or dysmenorrhea [problems with menses] or even full loss of period due to less estrogen and progesterone). While we’re excited to have the energy to be busy bees (or at least feel like we can be), our bodies are at work paying the price of chronically high cortisol levels. This can cause long-term changes to physiology and metabolism, such as:

- Elevated blood lipids (i.e., cholesterol, triglycerides). This puts a significant stress on the liver, because it requires that the lipids be repackaged and sent to cells to be stored.

- Breakdown of skeletal muscle. As we discussed, cortisol is catabolic – this means mobilizing the amino acids in skeletal muscle for use elsewhere, but in the case of adrenal fatigue, there is no need for them! So, we end up with wasted muscle mass and lot of difficultly making improvements in physical fitness and physique.

- Elevated blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C (a measure of saturation of heme with glucose in the past three months, used to diagnose type 2 diabetes). This also burdens the liver, but it (perhaps obviously) creates problems for metabolism; someone in this stage might have trouble losing weight or develop insulin resistance despite a healthy diet.

- Water retention. All of this excretion madness is a huge burden on the liver and kidneys. One of the compensatory reactions is to retain water. As a result, people in this stage might have some swelling in their hands and feet, and they might get that “puffy” sensation in their face.

So, if all this subtle damage is being done, how is it that people in this phase feel fine? It’s simple: the cortisol. Cortisol activates our sympathetic nervous system and those catecholamines I mentioned earlier (also known as adrenaline or epinephrine and norepinephrine) that keep us running at warp speed like Energizer bunnies. However, one of the signs of late stage two adrenal fatigue is that people find themselves having huge fluctuations in energy at inappropriate times of day (like having a “second wind” at night without doing anything to instigate it).

So, if all this subtle damage is being done, how is it that people in this phase feel fine? It’s simple: the cortisol. Cortisol activates our sympathetic nervous system and those catecholamines I mentioned earlier (also known as adrenaline or epinephrine and norepinephrine) that keep us running at warp speed like Energizer bunnies. However, one of the signs of late stage two adrenal fatigue is that people find themselves having huge fluctuations in energy at inappropriate times of day (like having a “second wind” at night without doing anything to instigate it).

At this point, most people will start to self-medicate in some way or another. This might include upping the coffee intake or experimenting with adaptogenic herbs or stimulating vitamins. Here are some signs that we might need to put down the stimulants and visit a practitioner instead:

- Unexplained weight loss or gain

- Changes in blood sugar regulation, like insulin resistance or hypoglycemia

- Dyslipidemia (elevated or abnormal triglycerides or cholesterol)

- Mood swings

- Decreased sex drive

- Fatigue with insomnia (especially feeling “tired and wired” in the evenings)

The bottom line is that Phase Two of adrenal fatigue is way easier to treat that Phase Three, but most people don’t seek any help until Phase Three hits. If any of the above is happening and seems inexplicable, it may be adrenal fatigue, and there are scientific ways to have adrenal function assessed – how to test the adrenals and what other conditions might be at play is all included in Part 2 of this series!

The unfortunate reality is that, at some point, the adrenal glands aren’t able to keep up, and that is phase three.

Phase Three: Burnout Phase

Phase Three adrenal fatigue, also called the Exhaustion or Burnout Phase, is where health starts to crash in a significant, scary way. Essentially, the pregnenolone steal has failed: we can’t make cortisol at the rate our body demands, and the whole system crashes. This phase is really where clinical intervention is often necessary, because leading a functional life can be incredibly challenging at this point. The medical language around this issue can be very dramatic at this point: “collapse of vital systems” being an example.

Phase Three adrenal fatigue, also called the Exhaustion or Burnout Phase, is where health starts to crash in a significant, scary way. Essentially, the pregnenolone steal has failed: we can’t make cortisol at the rate our body demands, and the whole system crashes. This phase is really where clinical intervention is often necessary, because leading a functional life can be incredibly challenging at this point. The medical language around this issue can be very dramatic at this point: “collapse of vital systems” being an example.

Some of the signs and symptoms of adrenal fatigue include:

- Severe fatigue that is persistent regardless of the amount of sleep one gets

- Heart palpitations

- Hypoglycemia

- Low blood pressure

- Joint pain (likely due to very high systemic inflammation)

- Frequent infection (including colds and flus)

This symptom pattern may include either a progressive series of worsening crashes or may be an extended acute attack, an this can be a result of even the smallest stressor. For most people, the symptoms are so severe that they must seek medical help (as I did when I was struggling with adrenal fatigue!). Depending on the type of practitioner, medications may be used to treat the symptoms rather than to treat the adrenal problem itself (for example, antidepressants or sleeping pills may be prescribed). Unfortunately, there is no medication that can magically fix adrenal fatigue, but there are methods for measuring and then monitoring adrenal function that can enhance recovery times (we’ll talk more about this in Parts 2 & 3 of this series).

Having been here myself, I know that this stage of adrenal fatigue is much more than feeling tired all the time (which is the really simple diagnostic that a lot of people use to convince themselves they must have adrenal fatigue).

The Bottom Line

Since we know that adrenal fatigue is a real phenomenon and understand the underlying physiology, we can now review the testing necessary to assess whether someone has adrenal fatigue. Check out diagnostic information and other cortisol disorders (plus conditions that might look like adrenal fatigue) in Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue: Part 2 (coming soon!)!

Citations

Giebels V, Repping-wuts H, Bleijenberg G, Kroese JM, Stikkelbroeck N, Hermus A. Severe fatigue in patients with adrenal insufficiency: physical, psychosocial and endocrine determinants. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37(3):293-301.

Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia, US; Saunders Medical; 2000.

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

Peet A. Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

Tanriverdi F, Karaca Z, Unluhizarci K, Kelestimur F. The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome. Stress. 2007;10(1):13-25.