I recently released my new gut microbiome e-books, The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook (released this week!), the culmination of nearly six years of intense research and writing. Even longer, more detailed versions of both e-books are in the works for a pair of upcoming in-print books that were delayed due to covid-19, but I didn’t want you to have to wait for this incredibly valuable information. Within these e-books, I discuss key ways to support a healthy gut microbiome that have not yet permeated conventional medicine, alternative health, or health-conscious communities. Quite simply, there’s actionable results from quality scientific studies discussed in these e-books that no one else is talking about. And our health stands to benefit from making this information mainstream. To write these e-books, I drew from thousands of different scientific studies, most of which were published within the two to three years since this is such an active area of research.

I recently released my new gut microbiome e-books, The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook (released this week!), the culmination of nearly six years of intense research and writing. Even longer, more detailed versions of both e-books are in the works for a pair of upcoming in-print books that were delayed due to covid-19, but I didn’t want you to have to wait for this incredibly valuable information. Within these e-books, I discuss key ways to support a healthy gut microbiome that have not yet permeated conventional medicine, alternative health, or health-conscious communities. Quite simply, there’s actionable results from quality scientific studies discussed in these e-books that no one else is talking about. And our health stands to benefit from making this information mainstream. To write these e-books, I drew from thousands of different scientific studies, most of which were published within the two to three years since this is such an active area of research.

Two questions that have arisen are: How does this information impact the Autoimmune Protocol? And, should I follow the AIP or the Gut Health Diet (which I also think of as a nutrivore diet)? Let me begin answering these questions by explaining my process in creating these new resources.

My Approach to the Scientific Literature

First, let me explain my approach to scientific research in general because it’s quite different from a lot of other leaders in health-conscious communities. The main reason my approach is different is because, well, I’m actually trained as a scientist. I used to be a medical researcher (I have a Ph.D. in Medical Biophysics) before my health struggles forced me onto an alternate path, which of course, led me to where I am now. I consider myself a health educator and, in many ways, a science translator. (Read more in About Dr. Sarah Ballantyne, PhD, Dr. Sarah’s Story and My Personal Journey as a Blogger.)

First, let me explain my approach to scientific research in general because it’s quite different from a lot of other leaders in health-conscious communities. The main reason my approach is different is because, well, I’m actually trained as a scientist. I used to be a medical researcher (I have a Ph.D. in Medical Biophysics) before my health struggles forced me onto an alternate path, which of course, led me to where I am now. I consider myself a health educator and, in many ways, a science translator. (Read more in About Dr. Sarah Ballantyne, PhD, Dr. Sarah’s Story and My Personal Journey as a Blogger.)

For years, I did research in critical care medicine (my two main projects were studying endogenous protective enzymes in the liver during Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, and stem cell-based gene therapy targeting angiogenic growth factors as a treatment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) and cell biology (I identified a new tumor suppressor gene involved in breast and colon cancer that prevents cell transformation via regulation of tight junctions in epithelial cells). I got to use some super cool technologies in my experiments, my research won awards, and I have published in some of the top scientific journals.

My extensive experience of actually performing scientific research gives me an appreciation for the effort and passion that goes into scientific studies, as well as knowing the academic scientific research community intimately. It also allows me to read scientific papers with a strong knowledge base on the subject matter as well as on experimental methodology and on statistical analysis (my B.Sc. is in honors physics so statistics and I go way back).

So, you’ll never hear me saying dross like “that experiment was performed in mice so it has no relevance to humans” (if it’s a  mechanistic study, which most animal experiments are, it’s immensely relevant to us because it explains why an effect happens), or “that human study has a small sample size so we should ignore the data” (statistical power is related to standard deviation and magnitude of effect, so you don’t always need a huge sample size to prove an effect). And, you’ll never hear me spout conspiracy theories, bash scientists as bias (99.9999% of them aren’t—fewer than 1 in 1000 peer-reviewed scientific papers are retracted and more often than not this is due to an honest mistake), or disregard a study just because it doesn’t confirm my beliefs (I’m completely open to new science challenging my conclusions and I will always let you know when new data changes the landscape with regards to a health topic).

mechanistic study, which most animal experiments are, it’s immensely relevant to us because it explains why an effect happens), or “that human study has a small sample size so we should ignore the data” (statistical power is related to standard deviation and magnitude of effect, so you don’t always need a huge sample size to prove an effect). And, you’ll never hear me spout conspiracy theories, bash scientists as bias (99.9999% of them aren’t—fewer than 1 in 1000 peer-reviewed scientific papers are retracted and more often than not this is due to an honest mistake), or disregard a study just because it doesn’t confirm my beliefs (I’m completely open to new science challenging my conclusions and I will always let you know when new data changes the landscape with regards to a health topic).

I don’t look for studies that support my assertions, but instead I try to represent the current state of knowledge on that topic, if there’s enough data to reach scientific consensus (something I value immensely), otherwise where the majority of data is currently pointing, the limits of current human knowledge, where results need to be confirmed (and yes, we need more funding for confirmation and replication studies!), and where conflicting data indicates nuance, context and a role for bioindividuality (for example, genetic contributors). And, I will always take the time to explain the scientific evidence behind every recommendation, so that your day-to-day choices can be empowered and informed by an appreciation for and understanding of the relevant science.

Why the Gut Microbiome Is So Important

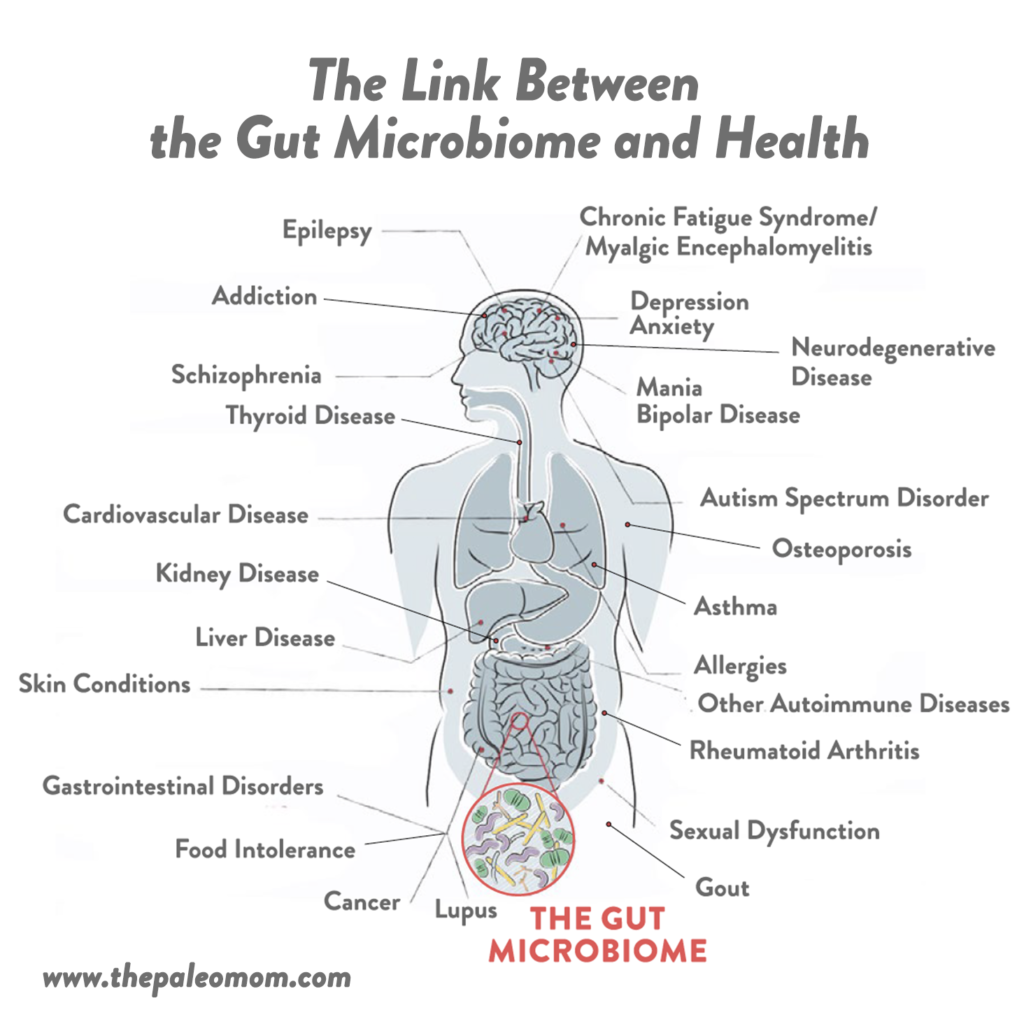

Our gut microbes perform many different essential functions that help us to stay healthy. These include digestion, vitamin production, detoxification, control of gut barrier integrity, regulation of cholesterol metabolism, providing resistance to pathogens, immune regulation, neurotransmitter regulation, regulation of gene expression, and more! Every human cell is impacted by the activities of our gut microbes.

A healthy gut microbial community is essential for our health.In fact, at least 90% of all disease can be traced back to the health of the gut and our gut microbiomes (see also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?). To date, an aberrant gut microbiome has been linked to conditions as wide-ranging as cancer, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, anxiety, depression, neurodegenerative diseases, autism, autoimmune disease, ulcers, IBD, liver disease, gout, PCOS, osteoporosis, systemic infections, allergies, asthma, infection susceptibility and more!

Quite simply:

- We can’t enjoy good health long-term without having a healthy and diverse gut microbiome.

- Diet is the single biggest influence on the composition and metabolic activity of the gut microbiome.

- Ergo, a diet can’t be a health-promoting diet unless it supports the health of our gut microbiome.

Studies show that the Paleo template leaves room for improvement when it comes to the gut microbiome. A 2019 study evaluating how long-term Paleo diet adherence affects the gut microbiome showed an alarming reduction in Roseburia and Bifidobacterium species. The study participants ate an average of 7 servings of vegetables per day, mostly non-starchy vegetables (average carbohydrate intake was only 90 grams), and the authors attributed the negative impact on the gut microbiome to low intake of resistant starch, a prebiotic found in abundance in roots and tubers. See Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding and Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome. The Autoimmune Protocol has yet to be similarly evaluated, but a 2019 study in patients with IBD showed that 11 weeks of AIP (6 week transition followed by 5 weeks of maintenance) caused expression changes in 324 genes, including upregulation of functional pathways associated with gut mucosal healing, which could be mediated through improvements in gut microbiome composition.

Save 70% Off the AIP Lecture Series!

Learn everything you need to know about the Autoimmune Protocol to regain your health!

I am loving this AIP course and all the information I am receiving. The amount of work you have put into this is amazing and greatly, GREATLY, appreciated. Thank you so much. Taking this course gives me the knowledge I need to understand why my body is doing what it is doing and reinforces my determination to continue along this dietary path to heal it. Invaluable!

Carmen Maier

I wanted to know if and how we can improve the Paleo and AIP diets so that they best support the gut microbiome. As I waded into the extensive scientific literature on the gut microbiome, and specifically the intersection between diet and lifestyle and supporting a healthy and happy community of gut microbes, I decided the only way to do this right was to leave all of my previously established conclusions about which foods are good or bad at the door. The best way to apply the insights from this field of scientific research to the Paleo and AIP templates was to first forget about the Paleo and AIP templates.

In my research, I became obsessed with understanding how healthy food choices benefit us, not directly, but instead via improving the gut microbiome. As I gathered information, I was very intentional to follow the science wherever it led, and I made a concerted effort to eschew diet dogma and consider the scientific research on the gut microbiome as objectively as I possibly could (see also Ditching Diet Dogma).

In my research, I became obsessed with understanding how healthy food choices benefit us, not directly, but instead via improving the gut microbiome. As I gathered information, I was very intentional to follow the science wherever it led, and I made a concerted effort to eschew diet dogma and consider the scientific research on the gut microbiome as objectively as I possibly could (see also Ditching Diet Dogma).

So, in my new e-book The Gut Health Guidebook, I build a new diet for general health from the ground up based on optimizing the gut microbiome.

Now, we can compare that Gut Health Diet to Paleo and the AIP and easily see both the incredible strengths of these dietary templates from a gut microbiome perspective in addition to where there is room for improvement. And it so happens that the room for improvement lies with a) those few eliminated foods that have long been the subject of much controversy, debate and criticism; and b) those points of contrast between the mainstream Paleo diet and the dietary patterns of hunter-gatherers.

Within both the Paleo and Autoimmune Protocol (AIP) dietary templates, of which I have been researching and writing (not to mention aligning my food choices with) for nine years, there are foods that have long been considered gray-area foods, or 80/20 foods. On paper, these foods are eliminated because they belong to one of the food groups (e.g., grains, legumes, dairy) that are excluded on the Paleo diet. But, these foods are well tolerated by many who eat them occasionally if not frequently. Highly related dietary templates include some of these foods—for example, rice is included on the Perfect Health Diet; dairy is included on the Primal Diet; and traditionally-prepared grains and legumes as well as raw grass-fed dairy are included on the Weston A. Price Diet. Others of these foods have caused much heated debate within the Paleo community over the years—such as potatoes and edible podded legumes like green beans, now considered Paleo because the original arguments against their inclusion in the Paleo diet fell apart under the slightest scrutiny (see also Potatoes: Friend or Foe of Paleo? and The Green Bean Controversy and Pea-Gate). And yet others of these 80/20 foods are the impetus for much valid criticism of the Paleo diet; for example, advocates of the Plant-based diet criticize the Paleo diet for omitting dried bean type legumes, for which there is ample scientific evidence indicating health-promoting properties.

The gut microbiome is the perfect lens through which to re-evaluate the merits of these foods. The added benefit? Doing so broadens the overlap between the Paleo template and other dietary approaches based in scientific evidence.

The Paleo diet was originally formulated to emulate the diet of our early ancestors who hunted and gathered their foods. However, there are some key dietary patterns of hunter-gatherers and early humans that were never integrated into the standard Paleo diet template. Aye, there’s the rub.

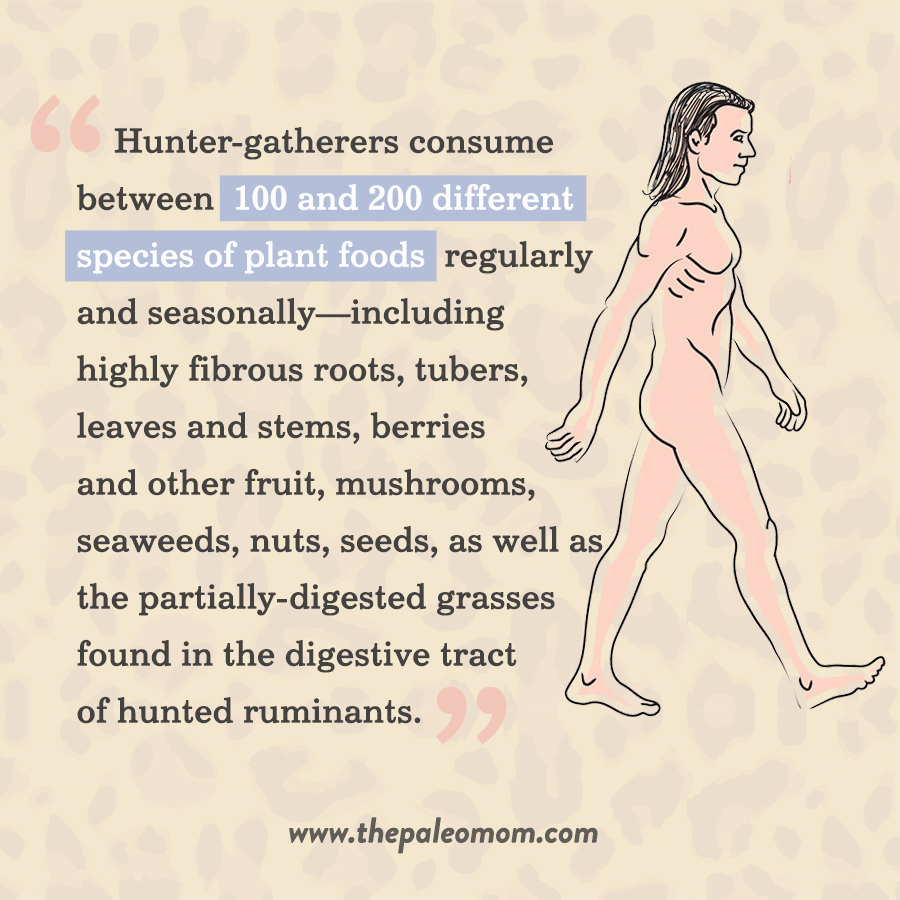

For example, most hunter-gatherers consume between 100 and 200 different species of plant foods regularly and seasonally—including highly fibrous roots, tubers, leaves and stems, berries and other fruit, mushrooms, seaweeds, nuts, seeds, as well as the partially-digested grasses found in the digestive tract of hunted ruminants—which amounts to an average fiber consumption of 45.7 grams daily, with some tribes consuming as much as 200 grams of fiber daily! Fiber intake guidelines have never been a feature of the Paleo diet, even though it is clearly a major point of contrast between the modern Western diet and the ancestral diet. See also The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers, Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?.

For example, most hunter-gatherers consume between 100 and 200 different species of plant foods regularly and seasonally—including highly fibrous roots, tubers, leaves and stems, berries and other fruit, mushrooms, seaweeds, nuts, seeds, as well as the partially-digested grasses found in the digestive tract of hunted ruminants—which amounts to an average fiber consumption of 45.7 grams daily, with some tribes consuming as much as 200 grams of fiber daily! Fiber intake guidelines have never been a feature of the Paleo diet, even though it is clearly a major point of contrast between the modern Western diet and the ancestral diet. See also The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers, Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?.

As another example, all legumes are omitted on the Paleo diet, despite evidence of consumption by hunter-gatherers and early humans. For instance, the tsin bean is the second most important food for the !Kung San that live in the regions where it grows (after mongongo nut). The leguminous seeds of the Acacia tree are extensively harvested and eaten by Australian aborigines. There’s also growing evidence that Neanderthals consumed wild legumes (most similar to peas and fava beans) and grains (most similar to oats and barley) as early as 46,000 years ago. While these facts in no way imply that we are adapted to a grain- and legume-based diet, they do indicate that not all legumes are as inflammatory as soy and peanuts, nor all grains as problematic as wheat. See also How Gluten (and other Prolamins) Damage the Gut, Worse than Gluten: The Agglutinin Class of Lectins, and The Green Bean Controversy and Pea-Gate.

As a final example, hunter-gatherers show a great preference for organ meat, reserving it for the upper echelons of their society (sometimes the hunters, sometimes the elders, and sometimes pregnant women) and eating it almost exclusively in times of plenty (leaving the muscle meat for the dogs if they have them [such as the Mbuti], and for scavengers if they don’t). Organ meat is the most nutrient-dense part of the animal, supplying nutrients that we can easily fall short on if we don’t consume it. See also Why Everyone Should Be Eating Organ Meat, Tips and Tricks for Eating more Offal, and The Best Foods and Nutrients to Support Liver Detox. Snout-to-tail eating is a feature of the AIP but was never integrated into mainstream Paleo.

By examining the impact on the gut microbiome, I learned that by banning all grains, legumes and dairy, we’re painting with a too-broad brush. As a result, we’re not just eliminating the inflammatory nutrient-poor members of these food groups; but, by throwing the baby out with the bathwater, we are also missing out on some of the nutritionally valuable members of these food families. Yes, some of the foods that we have been avoiding can be beneficial for many people (although there are still compelling reasons to omit them on the AIP, more on that below) . We can also look at contaminants (like pesticides, see for  example Water Quality and the Gut Microbiome) and food processing as contributors, and traditional food preparation techniques as necessary prerequisites. In addition, the gut microbiome research clearly demonstrates the need to put more emphasis on eating a wide variety of plant foods, increasing dietary fiber, and increasing the overall nutrient density of the diet by including more seafood and a snout-to-tail approach to animal foods.

example Water Quality and the Gut Microbiome) and food processing as contributors, and traditional food preparation techniques as necessary prerequisites. In addition, the gut microbiome research clearly demonstrates the need to put more emphasis on eating a wide variety of plant foods, increasing dietary fiber, and increasing the overall nutrient density of the diet by including more seafood and a snout-to-tail approach to animal foods.

I considered this 6-year-long deep dive into the gut microbiome research to be an opportunity to revisit how the Paleo and AIP communities evaluate the merits of individual foods, dietary patterns, lifestyles and biohacks—the goal was not to undermine or replace the principles of those templates, but rather to expand and deepen our collective understanding of optimal diet and lifestyle including the role of bioindividuality.

Yes, I am advocating for a more sophisticated and detailed approach for how we determine the merits of specific foods, rooted in how those foods impact the composition and activity of the gut microbiome, and considering nutrient density.

Building the Gut Health Diet

A variety of environmental, dietary, hormonal, and genetic factors orchestrate the incredible community of microorganisms that make up the human gut microbiome. In fact, our gut microbiota are shaped both by entirely modifiable determinants, such as the foods we eat and our lifestyle choices, to factors outside of our control, such as our gender and genetic makeup.

A variety of environmental, dietary, hormonal, and genetic factors orchestrate the incredible community of microorganisms that make up the human gut microbiome. In fact, our gut microbiota are shaped both by entirely modifiable determinants, such as the foods we eat and our lifestyle choices, to factors outside of our control, such as our gender and genetic makeup.

The resounding good news is that diet determines approximately 60% of microbiome composition. All other factors combined—including lifestyle, hormones, environmental exposures, drugs, supplements, toxins, gender, age and genetics—determine the remaining 40%. This means that the vast majority of the determinants of microbiome composition and its metabolic activity are within our control.

So far, the scientific research looking at how dietary patterns impact the gut microbiome have focused on understanding how established diets—those derived from traditional diets in geographical regions such as the Mediterranean diet and those that have been medically designed to achieve specific health outcomes like the DASH diet—affect the composition and metabolic activity the gut microbiome. What this research has revealed is fascinating! The proven health benefits of diets like the Mediterranean diet are, at least in part, mediated through the gut microbiome. But, figuring out what the best diet is for gut health using this type of research is like trying to reverse engineer an iPhone based on its most popular apps. We’re not even looking at the hardware!

So I took a granular approach in The Gut Health Guidebook, and I examined what compounds in what types of foods support what species of bacteria in order to build the best diet for our gut microbiomes from the ground up.

I approached the research methodically, first compiling the essential features of a healthy gut microbiome and well as specific links between bacterial species and chronic illness. Then I looked at:

- How proteins and individual amino acids impact the gut microbiome

- How different types of fats and how much fat we eat impact the gut microbiome

- How different types of carbohydrates and how many carbs we eat impact the gut microbiome

- How individual vitamin deficiency or excess impact the gut microbiome

- How individual mineral deficiency or excess impact the gut microbiome

- How phytochemicals, like specific polyphenols, impact the gut microbiome

- How sleep, circadian rhythms, fasting, stress, and activity impact the gut microbiome

From there, I looked at the research evaluating how specific foods impact the gut microbiome and identified essential gut health superfoods as well as foundational food groups (28 of them!). Then, I boiled this vast amount of information down to the 20 keys to gut health, as detailed in The Gut Health Guidebook and summarized in The Gut Health Cookbook.

If you’re well-steeped in the Paleo or AIP communities, and especially if you’re familiar with my research and writing, you won’t find many surprises in the Gut Health Diet.

The main takeaways are: Eat a nutrient-dense and highly-varied diet that is moderate-fat and moderate-carb, and that includes plenty of veggies, fruits, mushrooms, and seafood, rounded out with nuts, seeds, grass-fed meats, fermented foods, and phytochemical-rich foods like herbs, tea, coffee, cacao and extra virgin olive oil. It won’t surprise you to learn that refined and manufactured foods, preservatives, food additives, and common contaminants like pesticides, plastics, and heavy metals are terrible for the gut microbiome. Lifestyle factors are also essential, like getting enough sleep on a consistent schedule, entrenching a solid circadian rhythm, eating distinct meals instead of grazing, fasting overnight (12-14 hours, but not IFing), living an active lifestyle without overtraining, and managing stress.

The main takeaways are: Eat a nutrient-dense and highly-varied diet that is moderate-fat and moderate-carb, and that includes plenty of veggies, fruits, mushrooms, and seafood, rounded out with nuts, seeds, grass-fed meats, fermented foods, and phytochemical-rich foods like herbs, tea, coffee, cacao and extra virgin olive oil. It won’t surprise you to learn that refined and manufactured foods, preservatives, food additives, and common contaminants like pesticides, plastics, and heavy metals are terrible for the gut microbiome. Lifestyle factors are also essential, like getting enough sleep on a consistent schedule, entrenching a solid circadian rhythm, eating distinct meals instead of grazing, fasting overnight (12-14 hours, but not IFing), living an active lifestyle without overtraining, and managing stress.

The surprises? Yes, there are some. Most legumes (not soy or peanuts) are great for the gut microbiome (especially if traditionally prepared), as are grass-fed A2 dairy (like goat, sheep or camel dairy), some pseudograins, corn, rice, and gluten-free oats. Yes, these are the same aforementioned gray-area 80/20 foods included on related diets like the Perfect Health Diet, Primal, and the Weston A. Price diet.

The Implications for the AIP

My approach to researching for The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook is actually not much different from how I approached the scientific literature on the intersection between diet and lifestyle and immune function when I first started writing about the Autoimmune Protocol in early 2012, including compiling that information to write The Paleo Approach. It was very important to me during that process not to be influenced by Paleo yes-no foods lists. Instead, I methodically examined the scientific literature on nutrient, food and lifestyle links to various autoimmune diseases, as well as a granular examination of how individual compounds in foods impacted gut barrier health and immune function, as well as nutrients required for immune health.

My approach to researching for The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook is actually not much different from how I approached the scientific literature on the intersection between diet and lifestyle and immune function when I first started writing about the Autoimmune Protocol in early 2012, including compiling that information to write The Paleo Approach. It was very important to me during that process not to be influenced by Paleo yes-no foods lists. Instead, I methodically examined the scientific literature on nutrient, food and lifestyle links to various autoimmune diseases, as well as a granular examination of how individual compounds in foods impacted gut barrier health and immune function, as well as nutrients required for immune health.

Importantly, all of the recommendations derived from that research are still valid—this new deep dive into the microbiome literature adds to our understanding, rather than altering it.

In fact, the AIP is an excellent diet for gut health, as long as it is implemented with a strong nutrient-density focus that includes seafood, snout-to-tail eating, and consuming a wide variety and plenty of vegetables, fruit, and mushrooms, while avoiding going too low-carb or too high-fat. (All of my AIP educational resources, including The Autoimmune Protocol e-book, The Paleo Approach, and The AIP Lecture Series include these focuses.) The lifestyle tenets of the AIP is also on point for supporting a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. Why? Immune function is largely mediated by the gut microbiome, so it’s no surprise that the specific foods or nutrients linked to improved immune function are also linked to improved gut microbiome composition, and vice versa.

The current state of scientific evidence on optimal diet and lifestyle for the gut microbiome helps to explain why the AIP is such a powerful disease modifier for such a broad range of health challenges.

It’s also worth noting that because I’ve been working on this gut microbiome book for about 6 years, I have gradually incorporated the essential insights I gleaned in that research into the AIP during that time. For example, microbiome studies helped inform my recommendation to eat 8 to 10 daily servings of veggies as a minimum, including “eating the rainbow”, presented in my lectures for the AIP Certified Coach program and the AIP Lecture Series. Another example is the updates to the AIP announced 1.5 years ago, including an additional focus on gut health superfoods as well as shifting the order of reintroductions to prioritize gut health superfoods that are avoided in the Elimination Phase of the AIP (see Updates to the Autoimmune Protocol and The Autoimmune Protocol e-book).

Almost all of the 20 keys to gut health are already fundamental tenets of the AIP, if a little bit more explicitly laid out in The Gut Health Guidebook in terms of servings goals.

There are some gut microbiome superfoods (like nuts, seeds, coffee, chocolate, rice, gluten-free oats, lentils, split peas, garbanzo beans and grass-fed A2 dairy) that are initially excluded on AIP though, so what do we make of this? First, none of these foods are uniquely beneficial for the gut microbiome in the way that mushrooms or individual families of fruits and veggies are. So, none of these eliminated foods are required eating in order to have a healthy gut microbiome. Plus, there are still compelling reasons to avoid these foods during the Elimination Phase of the AIP, including their capacity to contribute to immune overactivation in susceptible individuals (see also The 3 Phases of the Autoimmune Protocol). It’s also worth noting that most of these foods are featured as early reintroductions (see also Reintroducing Foods after Following the Autoimmune Protocol). In fact, the AIP reintroduction stages have always included non-Paleo foods like rice and lentils that are great for the gut microbiome!

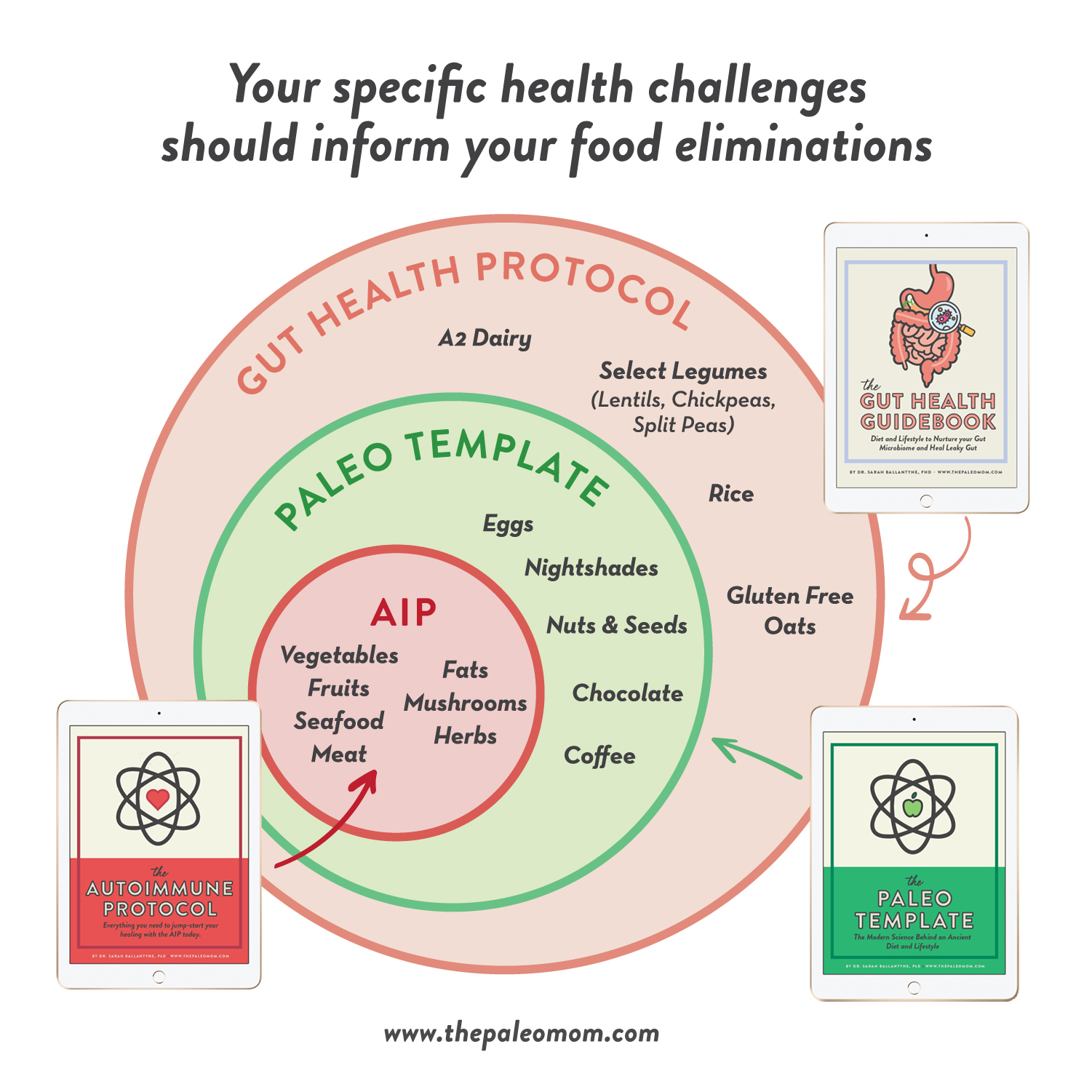

In The Gut Health Guidebook, I build a new diet for general health (rather than a diet to manage chronic illness like autoimmune disease), from the ground up, based on the gut microbiome, that merges everything the science currently tells us is healthful into one comprehensive approach. In the process of compiling this information, I have come to think of the AIP as a more therapeutic version of this Gut Health Diet, that additionally takes into account dietary autoimmune triggers. You can think of it this way: Instead of how we’ve traditionally viewed the AIP as a sub-diet of Paleo, you can now think of the AIP and Paleo as two different sub-diets of a Gut Health Diet (which I also think of as a nutrivore approach).

So, which diet to follow? That depends! With autoimmune disease, the most expedient pathway to healing remains the Autoimmune Protocol combined with a functional medicine approach. (The Autoimmune Protocol e-book is my most your up-to-date guide to jump-start your healing with the AIP today.) However, there are some takeaways from The Gut Health Guidebook that can be further integrated with the AIP to maximize support for the gut microbiome, including:

- The various families of vegetables are independently beneficial, so it’s best aim to consume 8+ daily servings of veggies, choosing from each of cruciferous veggies, the parsley family, leafy greens, roots and tubers, and the onion family on a daily basis. This can be rounded out with the ginger family, sea vegetables, and other vegetables. Mix up eating raw or cooked.

- Mushrooms aren’t vegetables, they’re fungi, and because they’re so uniquely beneficial for the gut microbiome, it’s helpful to start thinking of them as their own food group. It’s best to eat them daily, but at least aim for 2 to 3 times per week.

- Fruit is uniquely beneficial, even when eating plenty of veggies. It’s best to aim to consume at least 3 servings of fruit daily, choosing from each of the apple family, berries and citrus most days, rounding out with melons, tropical and subtropical fruits. It’s still important to keep fructose consumption below 40 grams daily, which typically means limiting to about 5 servings of fruit daily.

- There really isn’t any fat option as beneficial as a high-quality, fresh extra virgin olive oil, so this should be our Go-To. My preferred source is Fresh Pressed Olive Oil Club.

- Fish and shellfish are very nutrient-dense, rich in microbiome-friendly omega-3 fats, and contain the best protein for the gut microbiome. It’s best to aim to enjoy fish and/or shellfish daily!

- Gut microbiome composition is very sensitive to the nutrient-density of our diets, including those nutrients for which organ meat is the best source! It’s best to embrace snout-to-tail eating.

- Phytochemicals are also important to support gut microbial diversity. In addition to vegetables, fruit and mushrooms, rich sources of beneficial phytochemicals include tea (black, green and most herbal teas), herbs and spices.

You’ll note that none of these takeaways are at odds with the facets of the Autoimmune Protocol, but rather are only a slightly different emphasis that may only become relevant during troubleshooting. One could argue that recommending “8+ servings per day of a variety of vegetables, including eating the rainbow” is only semantically different from “8+ servings of veggies per day, choosing from each of the different veggie families.”

In summary, the information in The Gut Health Guidebook is very relevant to the AIP community, but its main takeaways have already been integrated into the AIP over the last several years.

A Bigger Diet Umbrella

The good news is that both AIP and Paleo are excellent diets for gut health, as long as they are implemented with a strong nutrient-density focus that includes seafood, snout-to-tail eating, and consuming a wide variety and plenty of vegetables, fruit, and mushrooms, while avoiding going too low-carb or too high-fat. (If you follow my work, you’ve likely got this covered.) However, I have come to think of Paleo and the AIP as sub-diets that fit under a bigger diet umbrella, the expanded diet defined in The Gut Health Guidebook, which for clarity we can call the Gut Health Diet or a nutrivore diet. Of course, the overlap in the Venn diagram of nutrivore versus Paleo versus AIP is huge; these are shades of the same diet, and which shade you choose depends on your overall health challenges and goals.

For example, if you’re following Paleo for optimal health and not to mitigate chronic disease, you could expand your diet to even further benefit your gut microbiome. If you’re following the AIP, these gut health superfoods are instead featured as early reintroductions after the elimination phase.

So yes, some of the 61 featured gut health superfoods in The Gut Health Cookbook are not “Paleo foods.” I view them as the foods that should never have been lumped in with the other members of their food group for elimination in the first place, at least for individuals without overt health concerns. The scientific evidence for their benefits to the gut microbiome is strong, but that doesn’t mean these foods will work for everyone. I encourage you to methodically experiment with these foods to establish how they work for you, respecting bioindividuality (I recommend following the Reintroduction Protocol). And, if they don’t work for you, that’s okay. None of them are uniquely beneficial for the gut microbiome in the way that fish, mushrooms, and the individual families of vegetables and fruit are. You can support a healthy and diverse gut microbiome even if you don’t regularly consume every single one of the 61 gut health superfoods featured in The Gut Health Cookbook. In fact, about 90% of the recipes in The Gut Health Cookbook are Paleo and more than half can easily be made AIP-compliant. (The Gut Health Cookbook includes a bonus printable with AIP recipe modifications.)

So yes, some of the 61 featured gut health superfoods in The Gut Health Cookbook are not “Paleo foods.” I view them as the foods that should never have been lumped in with the other members of their food group for elimination in the first place, at least for individuals without overt health concerns. The scientific evidence for their benefits to the gut microbiome is strong, but that doesn’t mean these foods will work for everyone. I encourage you to methodically experiment with these foods to establish how they work for you, respecting bioindividuality (I recommend following the Reintroduction Protocol). And, if they don’t work for you, that’s okay. None of them are uniquely beneficial for the gut microbiome in the way that fish, mushrooms, and the individual families of vegetables and fruit are. You can support a healthy and diverse gut microbiome even if you don’t regularly consume every single one of the 61 gut health superfoods featured in The Gut Health Cookbook. In fact, about 90% of the recipes in The Gut Health Cookbook are Paleo and more than half can easily be made AIP-compliant. (The Gut Health Cookbook includes a bonus printable with AIP recipe modifications.)

Most of all, and regardless of the dietary label that you most resonate with, I hope the information in The Gut Health Guidebook and the extensive recipe collection in The Gut Health Cookbook together provide motivation to choose more gut health superfoods, inspiration to try new foods, and serve as a launching point towards dietary tweaks to better support your gut microbiome.