When going Paleo, one of the hardest things for many people to give up are noodles (who doesn’t love pasta, fettuccini alfredo, or un ultra-comforting bowl of mac and cheese?!). Certain vegetables have come to the rescue as substitutes, like spaghetti squash and zucchini ribbons, but now another contender is grabbing the spotlight: Miracle Noodles. It used to be hard finding these noodles anywhere outside of Asian markets, but now that they’ve gained popularity among people reducing carbohydrates or avoiding grains, they’re popping up in more mainstream stores as well (three cheers for supply and demand!).

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

But, that leads us to the question… are Miracle Noodles Paleo? And more importantly, are they good for us?

What Are Miracle Noodles?

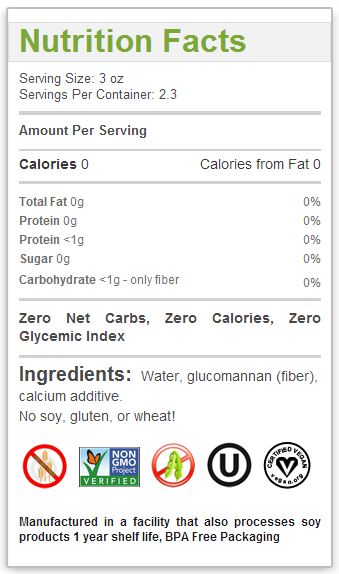

Miracle Noodles (also called Shirataki noodles or yam noodles) are gluten-free, soy-free, net-carb-free, and essentially calorie-free noodles made almost entirely of fiber. In fact, they have only three ingredients: glucomannan (a soluble fiber from the root of a Japanese plant called the konjac), water, and calcium hydroxide (also known as lime water, traditionally used to process corn and make tortillas). That doesn’t sound too bad, right?

Miracle Noodles (also called Shirataki noodles or yam noodles) are gluten-free, soy-free, net-carb-free, and essentially calorie-free noodles made almost entirely of fiber. In fact, they have only three ingredients: glucomannan (a soluble fiber from the root of a Japanese plant called the konjac), water, and calcium hydroxide (also known as lime water, traditionally used to process corn and make tortillas). That doesn’t sound too bad, right?

High-fiber intake is a hallmark of a healthy diet (see The Fiber Manifesto–Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?, The Fiber Manifesto–Part 2 of 5: The Many Types of Fiber, The Fiber Manifesto–Part 3 of 5: Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber) but recall that concentrated sources of specific fiber types aren’t always a great idea (see Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses and Mucilaginous Fiber: The Good, the Bad, and the Gooey).

To understand how Miracle Noodles can potentially impact our health, we can look at exactly what glucomannan is and how it interacts with our bodies—especially our gut microbiome!

Glucomannan: A Primer

Glucomannan has been extensively studied, both as a therapeutic supplement and as a food additive. And, the good news is that most of that research shows some exciting benefits from this fiber!

Multiple studies have shown that supplementing with glucomannan daily results in lower triglycerides, slightly lower systolic blood pressure, and lower total and LDL cholesterol (by interfering with cholesterol absorption, see The Fiber Manifesto–Part 4 of 5: Fiber, Cholesterol and Bile Salts), while improving (or at least not harming, depending on the study) the total cholesterol/HDL ratio. According to one (relatively small!) trial, patients with inflammatory bowel disease who added glucomannan to their diets reported an improvement in their bowel movements, stool consistency, abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhea, and overall well-being. And, a number of studies have shown that this fiber can help with constipation!

On top of that, glucomannan may be useful for blood sugar regulation and glycemic control. It’s been shown to reduce fasting blood sugar levels in both healthy and diabetic people, as well as reduce serum fructosamine (a gauge for blood sugar levels over the past 2-3 weeks) in diabetics.

Last but not least, glucomannan shows some promise as a weight-loss aid! An eight-week double-blind trial found that people taking 3 grams of glucomannan per day (1 gram before each meal) saw a significant drop in body weight compared to the control group. The same trend holds true in other trials on obese children. Although it’s not 100% understood, the reason seems partly due to improving satiety (sense of fullness) after meals, delaying gastric emptying, slowing bowel transit time, and increasing the amount of energy that gets fecally excreted.

So, What’s The Catch?

Does that all sound too good to be true? Anything with the word “miracle” in the name often is!

Consider this. Glucomannan fiber is made of glucose and mannose (hence its name!). Depending on the composition of someone’s individual gut microbiome, glucomannan can get fermented by beneficial bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—mostly acetate and propionate, with smaller amounts of butyrate. (In general, short-chain fatty acids are super beneficial and not only provide energy to our bodies, but also help mediate a number of disease processes—reducing our risk of diabetes, cancer, heart disease, metabolic dysfunction, intestinal diseases, among others! This is part of why SCFA-producing resistant starch gets so much hype, too.) But along with producing SCFAs, the glucose and mannose in glucomannan can feed less desirable bacteria that cause harmful infections or inflammation. For example, the pathogenic bacteria species Clostridium difficle, Klebsiella pneumonia and oxytoca, and Staphylococcus aureus can consume glucose and mannose and potentially increase their populations in response to glucomannan consumption. At least in theory! The problem is that, while most glucomannan research has been positive (and free from adverse effects), the existing trials have typically been short-term (a few weeks to a few months) and fairly small in size. So, it’s hard to know at this point whether any detrimental effects occur later on—when the composition of the gut microbiome has shifted—or in people with pre-existing imbalances of certain bacteria that could be sensitive to a sudden flood of glucomannan.

Also, keep in mind that Miracle Noodles are, essentially, a low-nutrient processed food. Konjac tubers (where glucomannan is derived from) have been used in China and Japan for at least 1000 years—traditionally being offered as presents to nobility and the Samurai, along with being used medicinally! But, glucomannan in its isolated form is a much more recent addition to the human diet. Whereas konjac root is rich in iron, calcium, manganese, copper, chromium, and phosphorous, these micronutrients are virtually absent from Miracle Noodles and other brands of glucomannan-based products. So, while glucomannan appears to offer health benefits when used as a supplement, if it replaces foods higher in vitamins and minerals (like zucchini noodles) instead of just being added to the existing menu, it can actually lower the nutrient-density of our diets!

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

What’s The Verdict?

So, back to our question: are Miracle Noodles it Paleo? And should we consider them a health-promoting food?

The answers are “no” and “sort of,” respectively! As a mixture of pure fiber and water, Miracle Noodles are more like a fiber supplement than the nutrient-dense whole foods that should comprise a Paleo diet. They don’t contain any protective phytochemicals or micronutrients occurring naturally in the konjac root.

And, our gut microbiomes probably aren’t used to receiving large, concentrated quantities of glucomannan fiber all at once. In certain people, there could be a risk of this fiber feeding the wrong bacterial populations and contributing to gut dysbiosis (though again, without more research, this remains speculative!).

For most people, there’s probably no harm in eating Miracle Noodles occasionally, in the context of an otherwise high-nutrient diet that features a mixture of other soluble and insoluble fibers. But, it might not be a good idea to make Miracle Noodles a dietary staple. Other Paleo-friendly noodles—like spiral-sliced zucchini (see AIP-Friendly “Spaghetti” and Meatballs and Bacon-Basil Zucchini “Pasta”), spaghetti squash (see Spaghetti Squash with Sage and Brown Butter), or even kelp noodles (see Why Seaweed is Amazing!, Paleo Pork Chow Mein, Paleo Shrimp Chow Mein, and Japanese-Inspired Whitefish and Noodle Soup)—can get the job done just as well as Miracle Noodles, with the added bonus of a better nutritional profile!

Citations

Avril A & Bodin L. “Effect of short-term ingestion of konjac glucomannan on serum cholesterol in healthy men.” Am J Clin Nutr. March 1995 vol. 61 no. 3 585-589

Chiu YT & Stewart M. “Comparison of konjac glucomannan digestibility and fermentability with other dietary fibers in vitro.” J Med Food. 2012 Feb;15(2):120-5.

Chua M, et al. “Traditional uses and potential health benefits of Amorphophallus konjac Ethnopharmacol.” J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128(2):268-78.

Gallaher CM, et al. “Cholesterol Reduction by Glucomannan and Chitosan Is Mediated by Changes in Cholesterol Absorption and Bile Acid and Fat Excretion in Rats.” J. Nutr. November 1, 2000vol. 130 no. 11 2753-2759

Keithley JK, et al. “Safety and Efficacy of Glucomannan for Weight Loss in Overweight and Moderately Obese Adults.” J Obes. 2013; 2013: 610908.

Keithley J & Swanson B. “Glucomannan and obesity: a critical review.” Altern Ther Health Med. 2005 Nov-Dec;11(6):30-4.

Loening-Baucke V, et al. “Fiber (glucomannan) is beneficial in the treatment of childhood constipation.” Pediatrics. 2004 Mar;113(3 Pt 1):e259-64.

Marsicano LJ, et al. “[Use of glucomannan dietary fiber in changes in intestinal habit].” G E N. 1995 Jan-Mar;49(1):7-14.

Puertollano E, et al. “Biological significance of short-chain fatty acid metabolism by the intestinal microbiome.” Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014 Mar;17(2):139-44.

Sood N, et al. “Effect of glucomannan on plasma lipid and glucose concentrations, body weight, and blood pressure: systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Oct;88(4):1167-75.

Staiano A, et al. “Effect of the dietary fiber glucomannan on chronic constipation in neurologically impaired children.” J Pediatr. 2000 Jan;136(1):41-5.

Suwannaporn P, et al. “Tolerance and nutritional therapy of dietary fibre from konjac glucomannan hydrolysates for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).” Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre. 2013;2(2):93-98.

Thomas WR. “Konjac gum.” Thickening and Gelling Agents for Food, 169-179.

Vido L, et al. “Childhood obesity treatment: double blinded trial on dietary fibres (glucomannan) versus placebo.” Padiatr Padol. 1993;28(5):133-6.

Vuskan V, et al. “Konjac-mannan (glucomannan) improves glycemia and other associated risk factors for coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes. A randomized controlled metabolic trial.” Diabetes Care. 1999 Jun;22(6):913-9.

Walsh DE, et al. “Effect of glucomannan on obese patients: A clinical study.” International Journal of Obesity. 1984;8:289-293.