SCIENCE SIMPLIFIED:

- The Autoimmune Protocol is not a low-carb diet and generally should not be combined with other diets (like GAPS, SCD, candida) that reduce carbohydrate intake via root vegetable and fruit restriction (unless directed by a qualified healthcare provider based on test results).

- Insulin has important biological roles beyond metabolism, including modulating the immune system and supporting thyroid and endocrine health. Insulin resistance is a problem, but we don’t want to lower our carbohydrate intake so low that we don’t secrete enough insulin for normal signaling either.

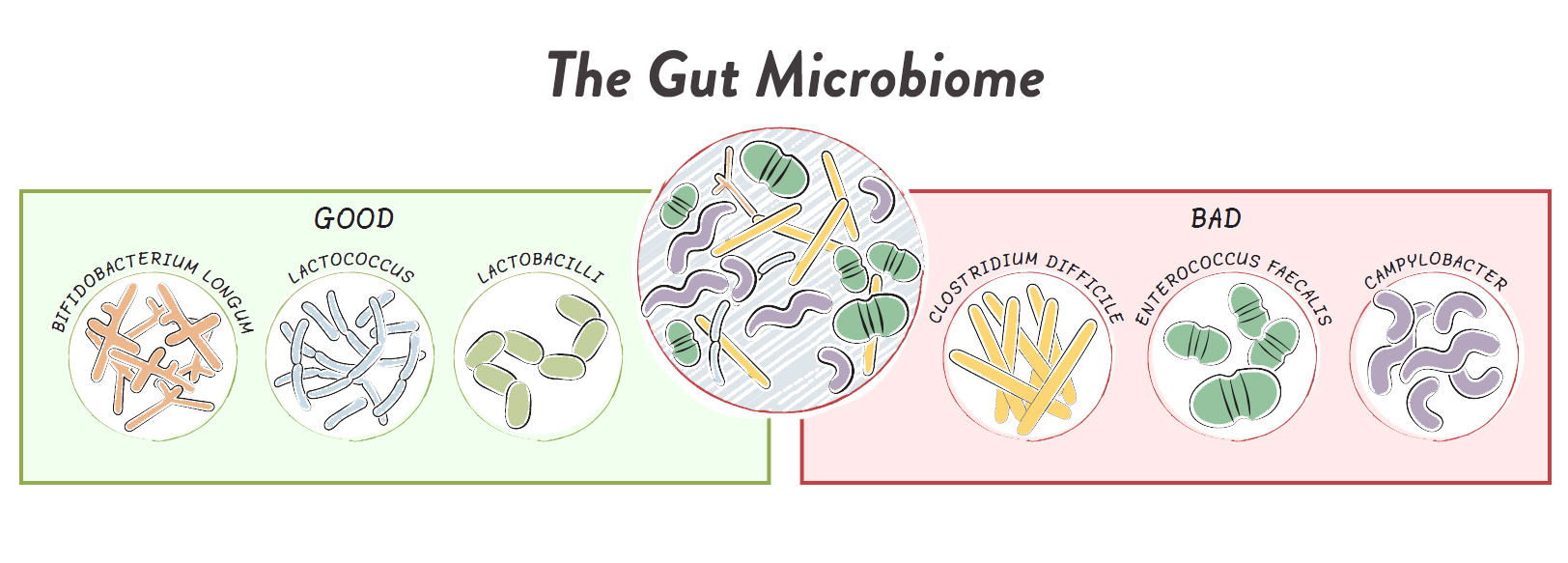

- Studies of low-carb Paleo and ketogenic diets show detrimental effects to the gut microbiome, including reduced microbial diversity and low growth of key probiotic strains of Bifidobacterium and Roseburia

- By considering the overlap between hunter-gatherer intakes and the AMDR, carbohydrate consumption should be in the range of 30% to 60% of total calories (this is a rough guideline with lots of wiggle room).

RELATED READING:

- The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body

- Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding

- Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome

One of the consequences of a nutrients-first approach is that the distribution of macronutrient intake tends to end up fairly balanced, with roughly a third, give or take, of calories from each of protein, fat and carbohydrate. See also The Importance of Nutrient Density, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?, Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers). This is what is referred to as balanced macronutrients¸ meaning that no macronutrient is low or high, i.e., not low-carb, not high-carb, not low-fat, not high-fat, not low-protein, not high-protein. And while the primary nutrient focus of the Autoimmune Protocol is sufficiency of micronutrient and fiber intake, there are some compelling reasons to avoid the pitfalls of macronutrient ratio extremes.

Eating too little of any macronutrient can result in malnutrition. Inadequate fat can decrease our absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and deprive us of essential fatty acids. Inadequate protein can reduce lean muscle mass, immune function, bone mineral density, and cause a host of problems related to deficiency of essential amino acids. Too few carbohydrates can mean insufficient fiber and micronutrients abundant in vegetables and fruits, including: vitamin C, B vitamins, vitamin K, potassium, magnesium, chromium, and phytochemicals including polyphenols, chlorophyll, carotenoids, isothiocyanates, and organosulfur compounds, all of which are important for disease prevention (see also How Many Carbs Should We Eat? and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body). The solution? We can balance our macronutrients by eating moderate amounts of carbohydrate, fat, and protein.

The healthy ratio of calories from fat, carbohydrates and protein can be determined by examining the overlap between hunter-gatherer macronutrient intakes (adjusted for errors caused by early ethnographers underestimating plant food intake due to interacting more with male hungers than female gatherers, see also Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherer) and the Accepted Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR) established by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine (using evidence from interventional trials with support of epidemiological evidence that suggest a role in the prevention or increased risk of chronic diseases, and based on ensuring sufficient intake of essential nutrients). When taken together, you end up with the following ideal distribution of macronutrient intake:

- ~20 to 35% calories from fat

- ~20 to 35% calories from protein

- ~30 to 60% calories from carbohydrate

It’s worth emphasizing that these calories would ideally all come from whole-food sources and that these ratios do allow for some wiggle room.

For example, people with one or two copies of the ApoE4 gene may do better with fat intake closer to 15% (see also Genes to Know About: ApoE). Furthermore, studies that cap healthy fat intake at 35% do not take fat quality into account, so it may be very healthy to have fat intake upwards of 50% of total calories, provided those fats come from extra virgin olive oil, fish, and pastured meats (see also Olive Oil Redemption: Yes, It’s a Great Cooking Oil!, Why Fish is Great for the Gut Microbiome, The Importance of Fish in Our Diets, Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): A Rockstar Nutrient). Carbohydrate quality is also important: sugars (even from whole food sources like fruit) shouldn’t make up more than 25% of total calories (and less than 10% of calories should come from added sugars, like honey or unrefined cane sugar); see also Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates, and Honey: The Sweet Truth About a Functional Food!). Also, high fiber intake is a key aspect of a healthy diet; see also The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?. Additionally, there may be some benefit to some stochasticity in macronutrient intake, highlighting that the occasional day where intake is way off of these ranges is totally okay. Finally, seasonal variation (typically more protein and fat in the winter, more carbs in the summer) may also be beneficial.

The take-home message: aim for roughly balanced macronutrients; but, if you find that you feel best outside of these ranges, and provided you aren’t dipping into macronutrient extremes (protein and fat should not dip below 10% of calories, and carbs should not dip below 20% of calories), go ahead and listen to your body.

Save 70% Off the AIP Lecture Series!

Learn everything you need to know about the Autoimmune Protocol to regain your health!

I am loving this AIP course and all the information I am receiving. The amount of work you have put into this is amazing and greatly, GREATLY, appreciated. Thank you so much. Taking this course gives me the knowledge I need to understand why my body is doing what it is doing and reinforces my determination to continue along this dietary path to heal it. Invaluable!

Carmen Maier

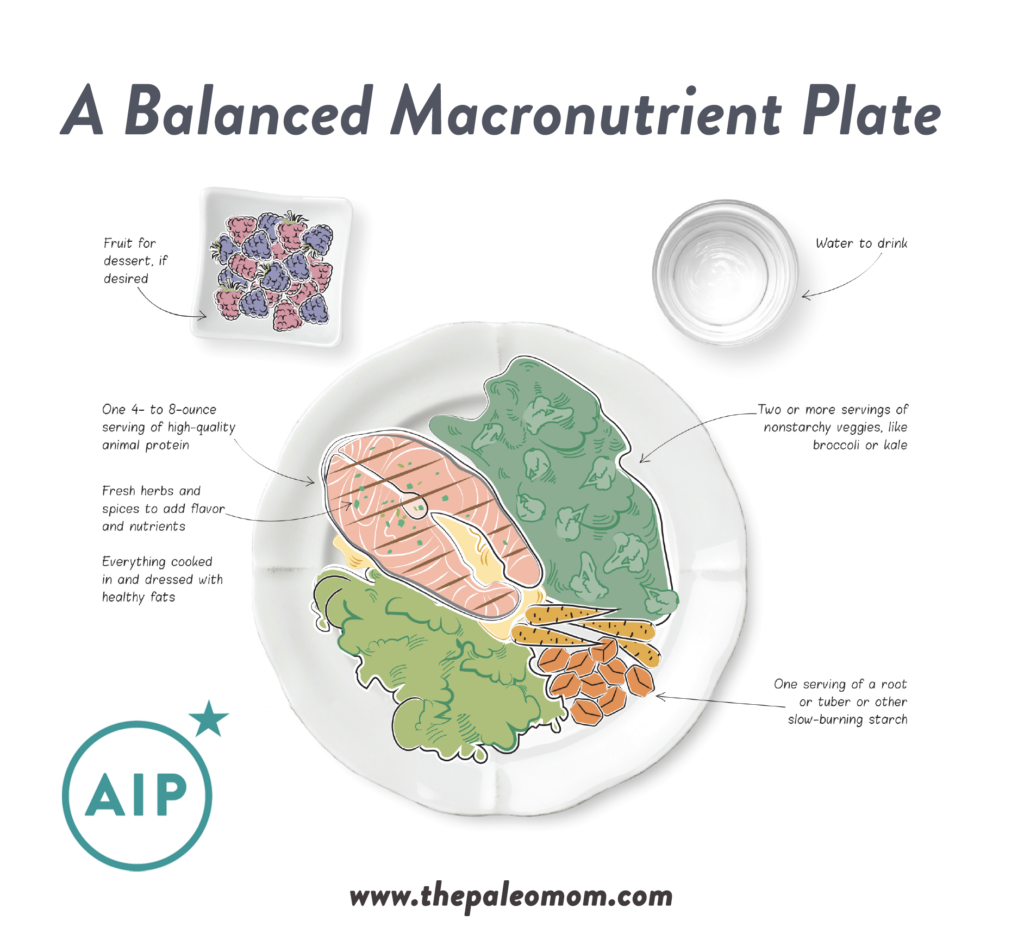

What Does a Balanced-Macronutrients Plate Look Like?

A good rule of thumb for a balanced macronutrient plate: About 6 to 8 ounces of meat or seafood, ½ to 1 cup of a starchy vegetable like sweet potato, 1 to 2 cups of nonstarchy veggies like broccoli or collards, and ½ cup of fruit for dessert. Go ahead and choose fattier cuts of meat or roast your veggies with a healthy fat, but don’t go out of your way to add fat to your plate. (There’s no need to douse your food in oil or salad dressing.) Scale up or down depending on your total caloric needs.

Avoid Carb-Phobia

It may surprise you to see recommended carbohydrate intake in the 30% to 60 % of total calories range when low-carb and ketogenic diets purport to cure just about every possible ill. Between the propaganda surrounding low-carb diets and the common pitfall of combining AIP with diets that limit vegetable consumption (such as keto, GAPS, SCD or the candida diet), some people end up adopting a too-low-carb version of the AIP, which can hinder healing, cause sleep disturbances, tank metabolism, and generally have you feeling pretty icky. (See also How Many Carbs Should We Eat?, The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body, 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food, How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut, Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised and Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding.)

When we consume carbohydrates, our blood sugar increases. In response to that rise in blood sugar, the pancreas releases the hormone insulin, which facilitates the transport of glucose into the cells of the body and signals to the liver to convert glucose into glycogen for short-term energy storage in liver and muscle tissues and into triglycerides for long-term energy storage in adipose tissues.

It’s a beautifully efficient system… until things go wrong. Chronically elevated blood sugar levels stimulate adaptations within cells, rendering them less sensitive to insulin. These adaptations may include decreasing the number of insulin receptors embedded within cell membranes and suppressing the signaling within cells that occurs after insulin binds to its receptor. This causes the pancreas to secrete even more insulin to lower the elevated blood glucose levels. This is called insulin resistance or loss of insulin sensitivity, when more insulin than normal is required to deal with blood glucose. When normal blood sugar levels can no longer be maintained, you get type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance is bad. It increases inflammation and affects metabolism, so it promotes weight gain and increases risk not only of obesity and diabetes, but also cardiovascular disease, many forms of cancer, asthma, allergies, PCOS, chronic kidney disease, many autoimmune diseases…. the list goes on.

So, if chronically elevated blood sugar levels makes you insulin resistant leading to health problems, then the key must be to not eat all those carbs, right? This thinking is what led to the now-debunked carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity and a surge in popularity of low-carb diets since the early 1990s. The fact is that insulin plays a lot of important roles in human health independent of its role in energy balance. So, while insulin resistance is clearly damaging, not eating enough carbs to secrete much insulin can also cause health challenges.

Insulin is a superhormone, with an array of functions in human physiology that far exceed its simplistic characterization as a metabolic hormone. And once we recognize these other roles of insulin, it’s easy to understand why too little insulin (or hindered insulin signaling as occurs in insulin resistance) can have negative consequences. Specifically, insulin is important for normal thyroid function, skeletal muscle metabolism, bone remineralization, central nervous system health, hormone regulation, and immune health.

The regularity effects of insulin on the immune system are of particular interest to autoimmune disease sufferers. The innate immune system is our first line of defense during infection or injury. Various immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages and natural killer cells) are activated by insulin and rendered more effective at their jobs. For example, insulin stimulates phagocytosis (the process of engulfing pathogens) by “eater” cell types. And, insulin enhances the cytotoxicity of cells that destroy virally-infected and cancerous cells. Elevated insulin causes generalized inflammation; however, when insulin resistance becomes advanced, the activity of these innate immune system cells becomes impaired.

The adaptive immune system recognizes specific pathogens and remembers them, why you only ever get chicken pox once and why vaccines work. Insulin activates adaptive immune system effector cells (T cells that drive immune attacks) as well as regulatory cells (T cells that constrain the system), also rendering these cells more effective. When insulin is high, two subtypes of T cells (Th1 and Th17, whose overactivity are implicated in allergic, immune and autoimmune conditions) become overactive while some types of regulatory T cells disappear. Blocking insulin signaling suppresses the activity and formation of both effector cells and regulatory cells.

Insulin signaling is extremely important for normal immune function. Its specific effects on immune cells explains why high insulin or insulin resistance is inflammatory, but also why insulin resistance is associated with allergic, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and a reduced ability to fight off infection.

While inflammation is a hallmark of insulin resistance, we also see increased susceptibility to infection in type 2 diabetes with protracted recovery time. However, the evidence is also mounting that very low-carbohydrate diets, such as ketogenic diets, have negative effects on our health that are often analogous to insulin resistance. In diabetes, the body is less sensitive to insulin signaling. During very low-carb intake, insufficient insulin is secreted for normal signaling. One recent study showed an increase in C-reactive protein (a blood borne marker of inflammation) during weight loss with a low-carb, high-fat but not a high-carb diet. Another study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed no benefits to the cytokine IL-6 or T cell numbers and activation with a ketogenic diet. And, in an animal study of malignant glioma, a ketogenic diet increased the numbers and activation of effector cells (especially Th1) while decreasing the population of regulatory cells. Long-term studies of ketogenic diets in children and adolescents with epilepsy show a trend towards reduced white blood cells counts, while also reporting increased susceptibility to serious infection, affecting 10 to 15% of study participants. Again, see The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body.

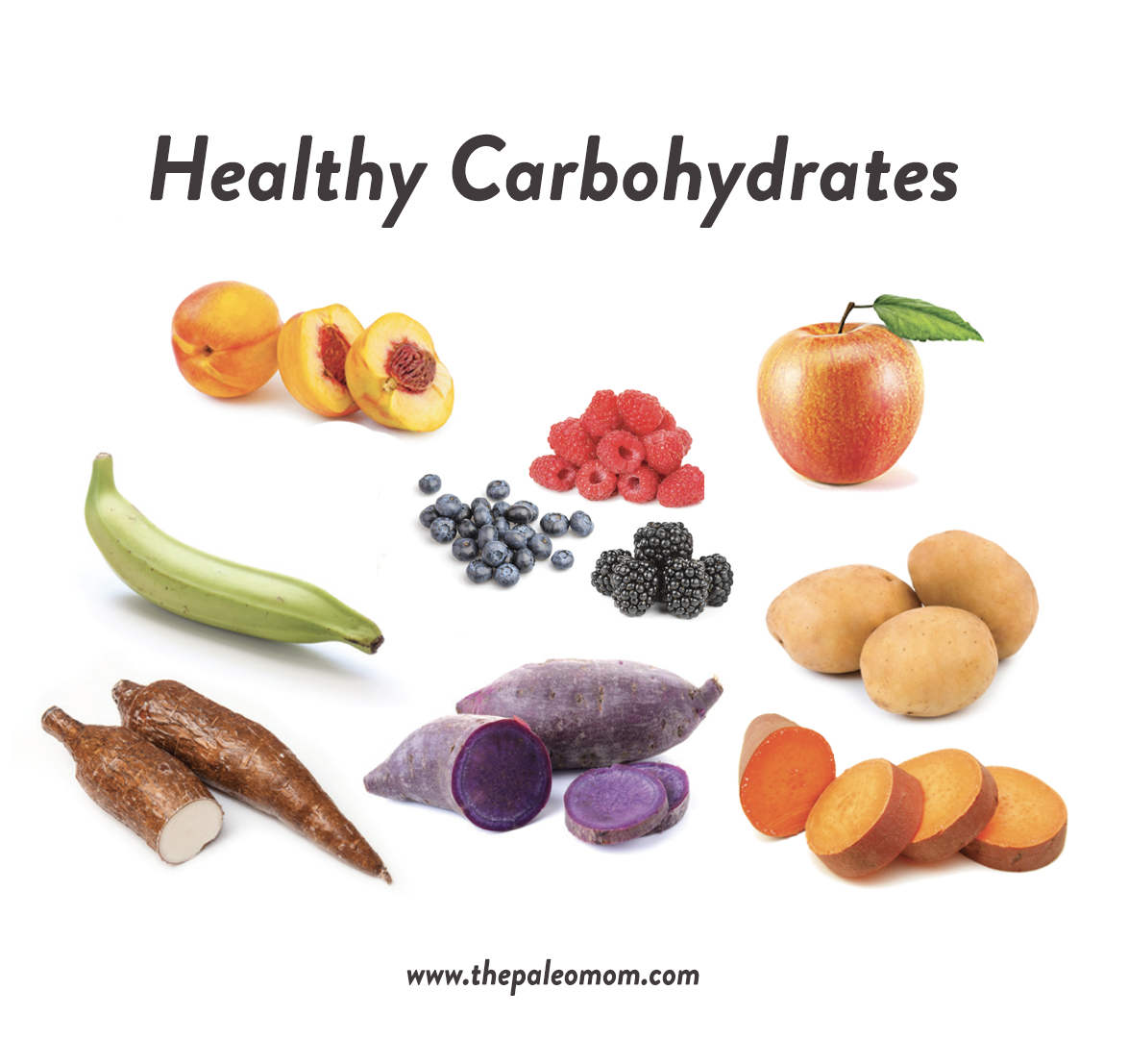

Maintaining insulin sensitivity is essential for health, but avoiding or drastically reducing carbohydrate intake isn’t necessary. Keeping blood sugar levels within a healthy “happy medium” range is easy if we limit ourselves to whole-food sources of carbohydrates (like starchy root vegetables and whole fruits) and eat them as part of a meal that includes animal protein and nonstarchy high-fiber veggies (like kale or broccoli). There really isn’t a good argument for limiting vegetable and fruit intake, including starchy vegetables rich in fermentable substrate that the gut microbiome loves (see also Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome and Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses)!

Maintaining insulin sensitivity is essential for health, but avoiding or drastically reducing carbohydrate intake isn’t necessary. Keeping blood sugar levels within a healthy “happy medium” range is easy if we limit ourselves to whole-food sources of carbohydrates (like starchy root vegetables and whole fruits) and eat them as part of a meal that includes animal protein and nonstarchy high-fiber veggies (like kale or broccoli). There really isn’t a good argument for limiting vegetable and fruit intake, including starchy vegetables rich in fermentable substrate that the gut microbiome loves (see also Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome and Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses)!

For those with insulin resistance or diabetes, measuring carbohydrate portions and keeping track of post-meal glucose levels is still advisable. It’s important to emphasize though, insulin sensitivity is also inextricably tied to how much sleep we get, how stressed we are and how active we are. In fact, studies show that one night of poor sleep causes higher insulin resistance than 6 months of bad diet. That means that dialing in lifestyle factors is a necessity for restoring and maintaining insulin sensitivity. See also 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food

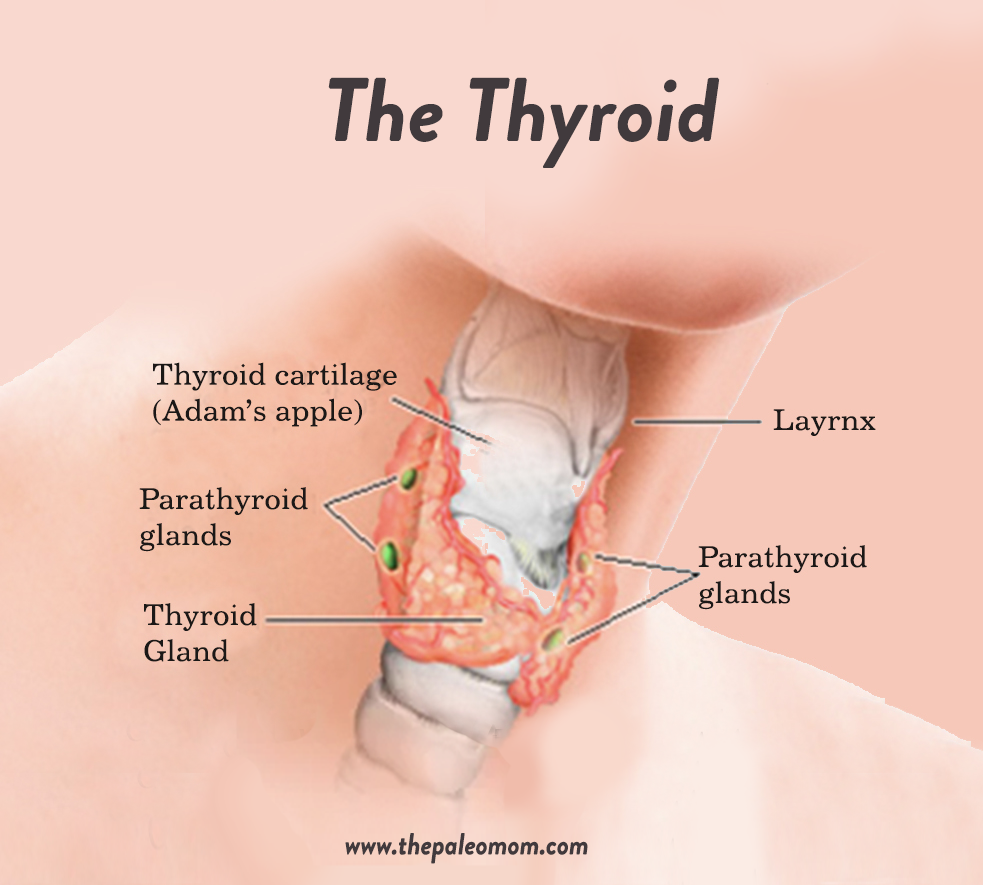

Carbohydrates, Insulin and Thyroid Function

For anyone with autoimmune thyroid disease or subclinical hypothyroidism (commonly comorbid with autoimmune disease), eating enough carbs while supporting insulin sensitivity is doubly important because insulin regulates thyroid hormones. See also Cruciferous Vegetables and Thyroid Disease

The thyroid gland produces hormones that control metabolism as well as influence other essential systems in the human body, such as the cardiovascular system, the immune system, and calcium homeostasis. Thyroid hormones increase our basal metabolic rate, control appetite, improve absorption of nutrients from the digestive tract, and control gut motility. They play an essential role in glucose metabolism and also stimulate the breakdown of fats.

The thyroid gland produces hormones that control metabolism as well as influence other essential systems in the human body, such as the cardiovascular system, the immune system, and calcium homeostasis. Thyroid hormones increase our basal metabolic rate, control appetite, improve absorption of nutrients from the digestive tract, and control gut motility. They play an essential role in glucose metabolism and also stimulate the breakdown of fats.

The prohormone thyroxine (T4) is produced in the thyroid gland and is then converted into the more active triiodothyronine (T3) by enzymes called deiodinases in multiple areas of the body. Type 2 deiodinase (D2) is present in the thyroid, central nervous system, pituitary (making its activity the most important for negative feedback on thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH), pineal gland, brown adipose tissue, placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart. It’s 1000 times more active than other deiodinases, and D2-catalyzed T3 production increases thyroid hormone signaling (blocking D2 causes localized hypothyroidism in various tissues). Importantly, its activity is upregulated by insulin and is decreased during fasting; insulin stimulates the conversion of T4 to T3 via D2 activity.

Insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes are linked with altered thyroid function, but both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are possible consequences. The prevalence of thyroid disease, including subclinical hypothyroidism, in patients with obesity or diabetes is significantly higher than in the general population.

Ketogenic diets decrease thyroid function. In a recent study of pediatric epilepsy patients following a ketogenic diet for seizure control, participants had an overall decrease in free T3 and concurrent increase in TSH. A whopping 1 in 6 participants developed hypothyroidism requiring L-thyroxine medication within the first 6 months of the study! And nearly half of those were within the first month! Of course, weight loss in general can reduce T3, but this is because T3 tends to be elevated in obesity and weight loss normalizes it. Studies that have investigated the effect of weight loss via calorie restriction on thyroid function have not identified an increased risk of hypothyroidism (T3 and TSH remain within normal lab ranges). Again see The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body and Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised.

Carbohydrates and the Gut Microbiome

Emerging evidence makes a strong case for moderate (not low) carbohydrate consumption to support a healthy gut microbiome. See What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?

When we consume digestible carbohydrates, they are broken down into simple sugars (mostly glucose) by our digestive enzymes and absorbed into our blood stream. But, each day, between about 20 and 60 grams of dietary carbohydrates escape degradation by our digestive enzymes and instead enter the colon. This is in addition to indigestible carbohydrates like resistant starches, plant cell wall polysaccharides and non-digestible oligosaccharides (i.e., fiber), and some di- and mono-saccharides (like sugar alcohols) that are resistant to digestion and/or absorption.

Originally, it was believed that, out of all the dietary factors that can impact the gut, fiber was the most important. However, it’s now known that high fiber consumption is but one contributor to a healthy and diverse gut microbiome.

Just as different animals are adapted to different diets, different bacterial species have different foods they can and cannot consume. Collectively, the gut microbiota is able to metabolize a variety of carbohydrates (sugars, starches, and fiber), amino acids, mucin, and the byproducts of other bacteria in the gut. Under normal conditions, about 60 grams of dietary carbohydrate is fermented each day by the gut microbiota into short chain fatty acids.

The quality and quantity of carbohydrates we consume daily is a major determinant of our gut microbiome composition (including other phyla such as archaea and fungi). Our gut microbiome composition is also sensitive to the amount and quality of the fats we consume (our gut microbes prefer moderate fat consumption mostly from omega-3 polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats), the quality of the protein we consume (their favorite is fish protein followed by chicken and red meat , see Why Fish is Great for the Gut Microbiome), phytochemical consumption (see also Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype? and The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!), the nutrient density of our diets, our hormone environment and our lifestyle choices (not to mention toxin exposure, drugs, pesticides, etc.).

There’s plenty of evidence that higher carbohydrate consumption, in addition to high-fiber consumption, is important for the gut microbiome. Last month’s new paper evaluating the effects of a long-term low-carb Paleo diet on the gut microbiome showed that around 90 to 100 grams of carbohydrate per day was not sufficient to promote the growth of key probiotic strains, including Bifidobacterium and Roseburia species, despite adequate fiber intake around 27 to 29 grams daily; see Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding. The control group consumed approximately double the carbohydrate grams daily. In addition, studies of the ketogenic diet have shown very concerning impacts on gut microbiome composition as well, attributable to inadequate carbohydrate consumption compounded with inadequate fiber intake (see How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut).

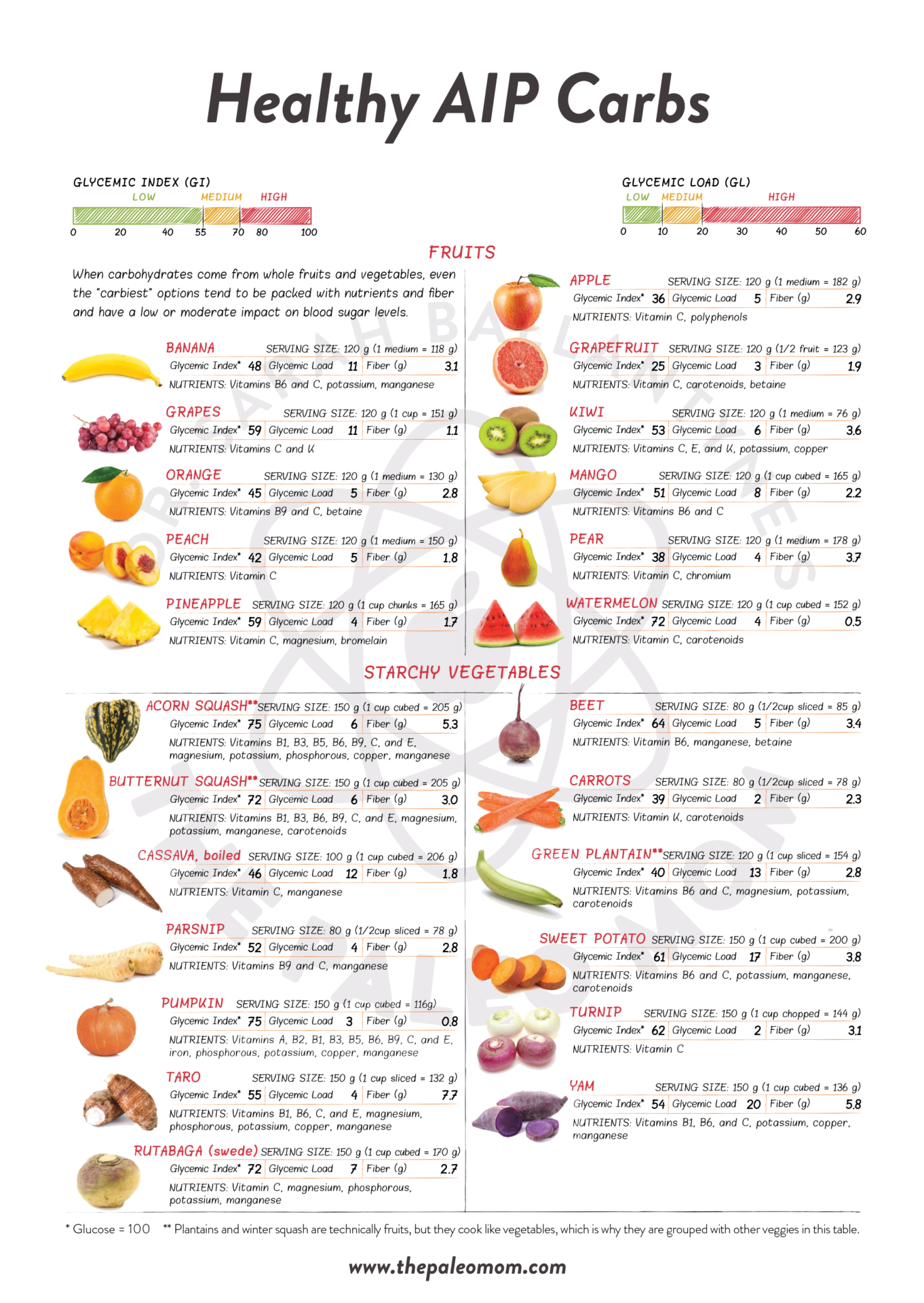

Healthy AIP Carbs

It’s not possible to pinpoint either an optimal number of carbohydrate grams to consume daily nor a minimum or maximum beyond the rough guidelines of 30 to 60% of total calories coming from carbohydrates, especially as a single recommendation across the board. The most important take-home message here is that the Autoimmune Protocol is not a low-carb approach and that root vegetables and starchy fruit like plantain and winter squash are not something to avoid. Fruit too, is a good source of carbohydrate on the AIP, provided fructose consumption is kept below 45 grams daily (somewhere around 10 to 20 grams daily is likely ideal); see also Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates.