One of the most common questions for those new to the Paleo diet is “How many grams of carbs, protein and fat should I eat?”. Actually, it’s a common question for many Paleo veterans too, especially when we find ourselves falling short of health goals. Macronutrients are the nutrients we need in big (“macro”) quantities, meaning fat, protein, and carbohydrate (rather than the micronutrients like vitamins and minerals that are even more vital for health but which we need in smaller quantities). And defining an optimal dietary macronutrient ratio (what percentage of our calories should come from carbs vs. fat vs. protein) is a contentious issue.

Both evolutionary biology and analyses of hunter-gatherer populations provide evidence that humans are omnivores, eating foods from both the plant and animal kingdoms, even in environments where obtaining one or the other is pretty difficult (such as the Inuit going to great lengths to find nutrient-dense vegetation!). Read more in The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 2: Physiological & Biological Evidence, and The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?.

Given the ongoing debate surrounding how much fat and carbohydrate we should be eating, hunter-gatherers offer valuable insights into what types of macronutrient ratios have supported healthy human populations. How much of their energy comes from gathered fruit and tubers? Is meat a frequent meal or a rarer delicacy? Is their fat intake high or low? Let’s have a look!

Hunter-Gatherer Analyses

Several studies have analyzed the macronutrient breakdowns of existing hunter-gatherers—with one of the most widely cited being Loren Cordain’s 2000 publication, “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets.” In this paper, Cordain, et al. looked at the ethnographic data for 229 hunter-gatherer societies (defined as having 100% reliance on hunting, gathering, and/or fishing for their food) and estimated the average intake of fat, carbohydrates, and protein.

Not surprisingly, the ranges were pretty diverse! By this paper’s calculations, the majority of hunter-gatherer populations (with some exceptions like the Inuit and Hadza, who I’ll talk about a bit later!) ate diets that fell within the following macronutrient ranges:

- 19 – 35% protein

- 22 – 40% carbohydrate

- 28 – 58% fat

On top of that, strong patterns emerged between geographical distance from the equator and different levels of macronutrients (as well as plant food to animal food ratios). Hunter-gatherer groups within 40 degrees latitude from the equator tended to consume about half of their diet as plant foods (and therefore had a higher carbohydrate intake). Populations farther than 40 degrees from the equator, on the other hand, had progressively higher intakes of animal foods (fat/protein) and lower intakes of plant foods—with those changes becoming more extreme in chilly circumpolar regions. (To help put that in geographical context, some cities that are around 40 degrees latitude include New York City; Denver; Madrid, Spain; and Naples, Italy.)

(From Cordain L, et al., 2000)

“FIGURE 2. Mean subsistence dependence in worldwide hunter-gatherers (n = 229) by latitude for gathered plant foods (A), hunted animal foods (B), fished animal foods (C), and fished + hunted animal foods (D).”

A more recent paper by Ströhle and Hahn looked more closely at the carbohydrate patterns associated with latitude, expanding on Cordain, et al.’s findings. This paper found that carbohydrate intake ranged from 3% to 50% of calories among the 229 populations analyzed, but that for societies residing between 11 and 40 degrees north or south of the equator, the range was almost universally 30% to 35% of total calories. As latitude increased from 41 degrees to 60 degrees and beyond (progressing away from the equator and towards the polar regions), average carbohydrate intake decreased from 20% to 9%. (Keep in mind, the number of populations living that far north or south, and eating that low of a carbohydrate level, were in the small minority! The vast majority of populations consumed at least a third of their total energy in the form of carbohydrates, according to this data.)

Problems With Estimation

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Despite researchers’ attempts to gauge hunter-gatherers’ macronutrient intake, the calculations are based on a lot of averages, guesswork, and in some cases, extrapolation from societies that aren’t “true” hunter-gatherers. For instance, Loren Cordain’s paper received some criticism from anthropologist Katharine Milton: in a response to his paper, she pointed out that many of 229 populations included in his data were “casual agriculturists” or hunted with modern guns—which may have altered their macronutrient intakes relative to what hunter-gatherers of the past could obtain. Once those questionable populations were removed, only 24 “true” hunter-gatherer communities were left! Likewise, Milton pointed out that some of the data in the ethnographic atlas Cordain drew from may have been skewed, because the ethnographers interacted more with the male hunters than they did female gatherers. That creates a potential bias for over-estimating the contribution of hunted foods versus gathered ones, and therefore the relative intake of fat/protein versus carbohydrate.

Apart from issues with studying “true” hunter-gatherer population, it’s notoriously hard to get a precise calculation of how much fat versus protein is consumed from hunted animal products. That’s due to a few different reasons. For one, most wild game is leaner than the grain-fattened (or even just grass-fed) animals raised on farms—and therefore tends to have a lower fat content and higher protein content than meat that’s been agriculturally produced. That makes it tough to draw a parallel between the nutritional composition of the meat we can get in the store, compared to the meat hunter-gatherers catch in the wild. And two, wild animals’ fat percent can vary based on their age, the season, their health, their gender, and a variety of other factors—meaning that even if we calculated the fat and protein content of one member of a certain species, it won’t necessarily be representative of other members of that same species throughout the year!

Another problem with estimating fat intake from wild game is the fact that hunter-gatherers often favor certain parts of a carcass, and—at least when food is abundant enough—will discard potentially edible parts of an animal instead of consuming the entire thing. One example of this was documented by Weston A. Price, a dentist who travelled the globe studying the diets of healthy, non-Westernized populations in the 1930s. In his book “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration,” Price described a practice he observed among Indians of the northern Canadian Rockies:

I found the Indians putting great emphasis upon the eating of the organs of the animals, including the wall of parts of the digestive tract. Much of the muscle meat of the animals was fed to the dogs. … The skeletal remains are found as piles of finely broken bone chips or splinters that have been cracked up to obtain as much as possible of the marrow and nutritive qualities of the bones. (Page 260)

So, this population literally threw away the animal parts most popular in the Standard American Diet (muscle meat) and selectively devoured organ meats and bones, which tend to be higher in glycine, certain minerals, fat-soluble vitamins, and fatty acids. While Price didn’t specifically measure macronutrient ratios, it’s fair to say the higher-fat (and higher-nutrient) parts of the animal were heavily favored (and higher-protein, lower nutrient parts were sometimes discarded entirely). As a result, the actual animal fat intake of hunter-gatherers may have been relatively higher (and protein intake relatively lower) than we’d predict from calculations that incorporate all edible animal parts. That can obviously throw off macronutrient estimates in a big way!

In other words, with our discussions of hunter-gatherers, we should keep in mind that macronutrient calculations are prone to some error. That doesn’t mean the data is worthless; just that we shouldn’t be treating it as totally precise!

What About Ketogenic Hunter-Gatherers, Like the Inuit?

Speaking of meat and fat intake, this is a great opportunity to clear up a myth about the Inuit: that they’re a hunter-gatherer culture that lives in sustained ketosis, due to their very low carbohydrate intake. The Inuit are sometimes cited as evidence that long-term ketosis must be safe for humans—otherwise the Inuit would be suffering from chronic diseases and early mortality on their traditional, very-low-carb diet… right?

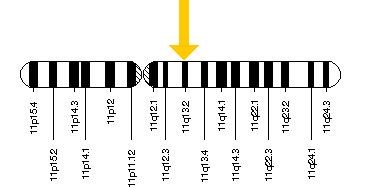

So, why did I say this was a myth? Because the Inuit aren’t actually in ketosis! As I explained in my blog post “The Link Between Meat and Cancer,” the Inuit have a special gene mutation that prevents them from entering ketosis (instead, they’re able to burn long-chain fatty acids for energy, which may help increase their body temperature in their notoriously cold climate). The mutation occurs on the CPT1A gene, and makes it so that any situation that would require relying on ketones (such as fasting) becomes virtually lethal to the Inuit. It also solves the previous mysteries as to why no elevated ketone levels have been found among the Inuit, and why they have normal glucose tolerance on their traditional diet (something not seen during ketosis, due to the physiological insulin resistance that occurs).

CPT1a gene

What’s more, even if the Inuit didn’t possess their unique gene mutation, their diet still wouldn’t be ketogenic due to its super high protein content (averaging 280 grams per day), since protein can be converted to glucose through the process of gluconeogenesis (and thus curtail ketosis) and due to some unique sources of dietary carbohydrates like the glycogen in whale blubber. In reality, we have no evidence of any hunter-gatherer society surviving on a ketogenic diet—even among the handful living in environments where it would theoretically be possible!

That said, while there aren’t any true ketogenic societies, there certainly are plenty of hunter-gatherers who consume fewer carbohydrates (and more fat) than recommended by the USDA and other official health organizations—and who remain enviably free from obesity and chronic disease. A detailed paper from Kaplan, et al. discusses the Nukak, Onge, Anbarra, Ache, Hiwi, Arnhem, and !Kung tribes as examples of such hunter-gatherer groups thriving on a higher fat intake without suffering our modern plague of diseases.

So, what does that tell us? Although long-term ketogenic diets don’t have any historical precedent (at least among entire populations), there are certainly examples of a higher fat intake (compared to what’s considered normal in industrialized nations) sustaining indigenous groups and protecting against disease. In other words, consuming a higher-fat diet of high quality, nutrient-dense foods can definitely be compatible with human health!

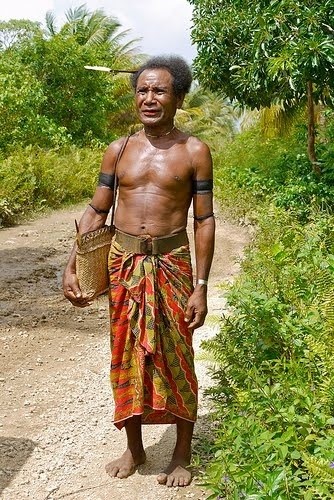

What About High-Carb Cultures, Like the Kitavans?

Just as the Inuit (and other far north populations) reside on the low-carb extreme end of the macronutrient spectrum, there are other cultures who reside on the high-carb end. The Kitavans of Papua New Guinea are one well-studied example. According to extensive research by Staffan Lindeberg, the Kitavans eat an average of 69% of their calories from carbohydrate, 10% from protein, and 21% from fat (mostly saturated coconut fat). And, to say their health is impressive would be an understatement! Virtually no cases of diabetes, ischemic heart disease, stroke, angina, or obesity were found among the Kitavans during the periods of study. A number of other traditional societies—such as the Hadza of Tanzania, the African Bantu, and the Gwi san—also subsist on higher carbohydrate intakes while retaining robust health.

Again, what does this tell us? Just as a higher-fat, non-ketogenic diet can be supportive of health, so can a higher-carbohydrate one. Clearly, macronutrient ratios aren’t the most important factor in whether or not a diet is supportive of long-term health!

Common Denominators

Clearly, there’s a lot of variation among different hunter-gatherer groups—and there doesn’t seem to be a “macronutrient sweet spot” where all hunter-gatherers inevitably land. But, these diverse populations do have quite a bit in common, no matter how much fat and carbohydrate they generally eat:

- Seasonal changes in macronutrient ratios. In stark contrast to the Standard American Diet’s year-round abundance of nearly every food, hunter-gatherer societies experience fluctuating availability of various plant and animal products—leading to seasonal changes in macronutrient ratios. For instance, the Hadza of Tanzania see a rise in meat consumption (and therefore fat and protein intake) during the dry season, when both humans and wild game start frequenting local watering holes. Various other tribes consume more carbohydrates when fruit, honey, and starchy roots are abundant, and rely more on hunting and fishing when energy-dense plant foods are harder to find.

- Cycles of feast and famine. As with fluctuating availability of different foods, fluctuating availability of food in general is an issue for hunter-gatherers! On a day-to-day, week-to-week, and month-to-month basis, hunting and gathering successes can wax and wane. Periods of scarcity and hunger are interspersed with periods of feasting and abundance, leading to cyclic changes in energy consumption.

- Micronutrient density. Regardless of general differences in macronutrient ratios, all hunter-gatherer populations consume a diverse array of wild, unprocessed plant and animal foods—bringing plenty of beneficial micronutrients and phytochemicals to the table. This is universal among populations that subsist on wild foods, and goes a long way towards protecting these groups from the chronic diseases plaguing the West.

- Fiber. Fiber intake of hunter-gatherers ranges from 50g to over 200g daily (compare that to the 25g daily recommended by the USDA). Even the animal-food-rich diet of the Inuit contains fibrous plant foods (berries, moss, corms, preserved flower buds, seaweed, and other goodies)! Across the board, unrefined, high-fiber plant foods are a frequent sight in hunter-gatherer diets, helping feed gut flora and contribute to an overall positive health profile.

What Does it Mean For Us?

I’m not a fan of trying to reenact what our Paleolithic ancestors did in the name of “getting healthy” and the same holds true for trying to emulate the diets of more recent hunter-gatherers! Our best bet is to use evolutionary history as a starting place, but turn to the scientific literature to figure out how different foods, diet patterns, macronutrients, and micronutrients effect our health. In fact, I’ve discussed some relevant science in these posts: New Scientific Study: Calories Matter, Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?, and Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised as well as ones already linked to above.

Yet, we can still take away some important points from the macronutrient ratios of hunter-gatherers. The biggest one is that a wide range of ratios can be supportive of human health, and it’s far from the most important thing when designing a nutritious diet! While hunter-gatherer diets don’t unanimously share a certain fat, carbohydrate, or protein intake, they do share a high concentration of micronutrients, plenty of fiber, and inherent fluctuations in both energy and macronutrient content. Those appear far more important than a specific fixed macronutrient ratio.

So, rather than worrying if you’ve eaten too many carbohydrates or fat grams, your mental energy might be better spent trying to squeeze a wide variety of fresh, high-quality, nutrient-dense plant and animal foods onto your plate (like organ meat, seafood, and tons of veggies!), and enjoying every bite!

Citations

Billings T. “The !Kung San’s main plant foods.” Beyond Vegetarianism. Accessed October 27, 2015.

Clement FJ, et al. “A Selective Sweep on a Deleterious Mutation in CPT1A in Arctic Populations.” Am J Hum Genet. 2014 Oct 23;95(5):584-589.

Cordain L, et al. “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92.

Heinbecker P. “Studies on the metabolism of Eskimos.” Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1928 Dec;80:461-475.

Hill K, et al. “Seasonal variance in the diet of Ache hunter-gatherers in Eastern Paraguay.” Human Ecology. 1984 Jun;12(2):101-135.

Kaplan HS, et al. “A Theory of Human Life History Evolution: Diet, Intelligence, and Longevity.” Evolutionary Anthropology. 2000:9;156-185.

Lindeberg S, et al. “Age relations of cardiovascular risk factors in a traditional Melanesian society: the Kitava Study.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1997 Oct;66(4):845-52.

Lindeberg S, et al. “Cardiovascular risk factors in a Melanesian population apparently free from stroke and ischaemic heart disease: the Kitava study.” J Intern Med. 1994 Sep;236(3):331-40.

Lindeberg S & Lundh B. “Apparent absence of stroke and ischaemic heart disease in a traditional Melanesian island: a clinical study in Kitava.” J Intern Med. 1993 Mar;233(3):269-75.

Milton K. “Hunter-gatherer diets-a different perspective.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):665-7.

Milton K. “Reply to L Cordain et al.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Dec:72(6);1590-1592.

Price W. “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration.” 2003. 6th ed. Keats Publishing: page 260.

Schnorr SL, et al. “Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers.” Nature Communications. 2014 Apr:5:3654.

Ströhle A & Hahn A. “Diets of modern hunter-gatherers vary substantially in their carbohydrate content depending on ecoenvironments: results from an ethnographic analysis.” Nutr Res. 2011 Jun;31(6):429-35.