The Paleo template is an educational foundation, based on scientific evidence, that informs our food choices. As such, it’s a flexible way of eating, and while there are strong themes when it comes to included foods, there are also few hard-and-fast rules and restrictions. Yet, I think some of us can feel a little “analysis paralysis” when it comes to implementing the Paleo diet in the context of the many opinions that exist on aspects of the Paleo diet, especially those distilled to soundbites, presented as rules with little (valid) explanation, or steeped in rhetoric or dogma. Is there a simple way to know how to make the best choices given seemingly endless options?

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

This may be an oversimplification, but we can lump together all the health-promoting nutrients in foods as “good stuff” and all the health-undermining compounds in foods as “bad stuff.” When evaluating the merits of an individual food, we can weigh how much good stuff is in that food versus how much bad stuff is in it. Some foods have tons of good stuff and no bad stuff – these are definite “yes” foods! We can eat plenty of them without guilt, knowing they’re entirely health-promoting. Other foods have tons of bad stuff and very little good stuff – these are the definite “no” foods and should be avoided the vast majority of the time.

This may be an oversimplification, but we can lump together all the health-promoting nutrients in foods as “good stuff” and all the health-undermining compounds in foods as “bad stuff.” When evaluating the merits of an individual food, we can weigh how much good stuff is in that food versus how much bad stuff is in it. Some foods have tons of good stuff and no bad stuff – these are definite “yes” foods! We can eat plenty of them without guilt, knowing they’re entirely health-promoting. Other foods have tons of bad stuff and very little good stuff – these are the definite “no” foods and should be avoided the vast majority of the time.

These extremes are where most health experts (even those outside the Paleo sphere) agree. There are no logical arguments against the health benefits of eating plenty of veggies, quality seafood, high quality (grass-fed or pastured) meat in moderation, healthy fats in moderation, herbs and spices, and fruit in moderation, and when possible buying organic, local, in-season, and consume foods as close to their natural state as possible. There’s also no question that refined and processed foods along with synthetic ingredients like food dyes and non-nutritive sweeteners are not doing any of us any favors. Where confusion arises is in the range of gray in between, foods that have compelling nutrition but substantial quantities of problematic compounds. And here’s where a more detailed conversation about the pros and cons of these foods becomes necessary.

These extremes are where most health experts (even those outside the Paleo sphere) agree. There are no logical arguments against the health benefits of eating plenty of veggies, quality seafood, high quality (grass-fed or pastured) meat in moderation, healthy fats in moderation, herbs and spices, and fruit in moderation, and when possible buying organic, local, in-season, and consume foods as close to their natural state as possible. There’s also no question that refined and processed foods along with synthetic ingredients like food dyes and non-nutritive sweeteners are not doing any of us any favors. Where confusion arises is in the range of gray in between, foods that have compelling nutrition but substantial quantities of problematic compounds. And here’s where a more detailed conversation about the pros and cons of these foods becomes necessary.

When it comes down to it, I think nutrient density paired with anti-inflammatory actions is the ultimate thing to look for in a food. But, if we ate foods that were ONLY these two things, we’d miss out on some nutritious options (and eating might be slightly less enjoyable, too!). Not every food is super nutrient-dense, nor does every food have known anti-inflammatory effects, so knowing which nutrients and characteristics to look for in a food is key. Let’s talk about the different compounds in foods that make them suitably good, bad, or in-between; then we’ll talk about how to make the best choices for our own bodies.

What counts as “good stuff?”

What counts as “good stuff?”

“Yes” foods are simply those that have tons of good stuff and not very much bad stuff. That means the food should contain either moderate amounts of a bunch of important nutrients or large amounts of a few essential nutrients (especially nutrients that are harder to get elsewhere), and not pack too much of a caloric wallop (you’ll sometimes hear this referred to as nutrients per calorie). So, what types of nutrients should we be on the look out for? Here are elements of a food that are ticks in the “good” column:

- Vitamins and minerals. These micronutrients are an aspect of healthy eating that needs to be emphasized more than ever, as consuming sufficient quantity of the full array of essential vitamins and minerals is essential for health. Some studies currently estimate that upwards of 90% of Americans are woefully deficient in at least one nutrient (and that’s counting fortified foods and supplements!) and when you break it down, there are certain super important vitamins and minerals that play profound roles in our health that the vast majority of us aren’t getting enough of. For example, 73% of us don’t ever get the RDA or zinc and 75% of us don’t get enough folate (see The Importance of Nutrient Density). When we consider the foods richest in essential vitamins and minerals, the same groups come up again and again as nutritional powerhouses: organ meat, seafood, and vegetables (especially leafy greens and cruciferous veggies) are our gold tickets. For more information about each of the vitamins and minerals, check out my Nutrients Wiki.

- Fiber. I’m on a personal mission to get everyone eating at least 30 grams of fiber every day. Why? It’s completely essential for health, even though it isn’t deemed an “essential” nutrient. However, we know that adequate fiber intake is essential for digestion, hormone regulation, toxin elimination, and a healthy microbiome. The foods richest in fiber will be vegetative (obviously, there is no fiber in animal matter!). I’ve written extensively about fiber on the blog before, especially in my epic Fiber Manifesto series. I recommend starting with The Fiber Manifesto – Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is It Good? and 5 Reasons to Eat More Fiber.

- Phytochemicals. These powerful micronutrients are another tick in the “yes” column for fruits and vegetables. Why? Phytochemicals are potent antioxidants found in plants, many of which prevent cancer, reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, regulate hormones and reduce inflammation while ensuring an efficient immune system. These compounds are often linked to the pigment of a plant, and the human body utilizes them in a variety of ways. There are many different types of phytochemicals, which I’ve described in the post The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals, and see also Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?.

- Probiotics. Another good thing to look for in a food is natural probiotics, found as soil-based organisms from the organic dirt on vegetables and in fermented foods. They improve the gut microbiome by encouraging growth of healthy bacteria and increase the bioavailability of certain nutrients. I talk about this even more in the post The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, and The Benefits of Eating Dirt.Essential Amino Acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. Even though we’ve identified about 500 different amino acids, only 20 are used to build the proteins in our bodies, and only nine of those are considered nutritionally indispensable, meaning that we absolutely have to get them from food—our bodies can’t make them. These nine essential amino acids are: isoleucine, histidine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan and valine. A further six amino acids are considered conditionally indispensable, meaning that while other amino acids can be converted into these, the process is so inefficient that most of the time we still need to get these from food. The remaining five amino acids are considered nutritionally dispensable, meaning that our bodies can make them in sufficient quantities provided there’s enough protein in our diets. Consuming complete protein sources that are easy to digest is key to getting sufficient quantities of all of the amino acids, which means eating fish, shellfish and quality meats (see Plant-Based Protein: What is its Role in the Paleo Diet?)

- Healthy fatty acids. Fatty acids, the building blocks of fats, are used not only for energy but also for many basic structures in the human body, such as the outer membrane of every single cell. There are many different fatty acids, each with different effects on, and roles in, human health. Key concepts when it comes to fatty acids is a balanced intake of omega-3 versus omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (meaning getting lots of DHA and EPA from seafood and grass-fed meat while limiting omega-6s from plant sources like vegetable oils, nuts and seeds), consuming heart-healthy monounsaturated fats like the oleic acid in avocado and olive oils, and moderating saturated fat intake. See Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?, Why Grains Are Bad–Part 2, Omega 3 vs. 6 Fats and Which Fats Should You Eat?)

These qualities are what I consider health-promoting, and they point toward a food being a “yes.” Noting how much of these nutrients are in each food is a worthwhile endeavor when trying to optimize our health, which is why I’ve started a wiki on my site of the ingredients included in my recipes (see Ingredients Wiki).

You may have noted that this list is heavily focused on micronutrients plus the building blocks of macronutrients. Why? In my extensive research of human physiology and biochemistry, I believe that we all need a well-balanced diet that includes all three macronutrients while focusing on micronutrient sufficiency (meaning we get all the micronutrients our bodies need). So, making food choices solely based on macro-nutrition is missing the mark (for more, see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insights From Hunter-Gatherers and The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat vs. Veggies?).

What counts as “bad stuff?”

What counts as “bad stuff?”

Emphasizing the many great things found in food is a wonderful way to implement a nutrients-first strategy for eating. But, there are complicating factors: the bad stuff. I define “bad stuff” as being anything that might negatively influence digestion or gut health, cause inflammation, cause cancer or otherwise detract from our health.

- Antinutrients. The term “antinutrients” refers to several groups of compounds that impede our ability to absorb nutrients or otherwise diminish the nutritive value of a food. Naturally-occuring antinutrients are found in plant foods, especially the seeds of plants (which includes all grains, legumes, but also nuts and seeds). Why? The “design” of most plants is to be consumed and excreted with at least intact seeds so that the plant will continue to grow in another area. So, while this helped plants to survive in the wild, it doesn’t help anything in the modern world (including our digestive tracts!). Some common antinutrients include phytates, prolamins, agglutinins, and digestive enzyme inhibitors. See Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?), Why Grains Are Bad Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, 3 Myths About Legumes — Busted! and Nuts and the Paleo Diet: Moderation is Key).

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

- Inflammatory compounds. Some foods are inherently inflammatory, meaning that they can trigger immune responses naturally. These foods are best avoided, especially for someone with chronic disease or other health concerns. One of the classic examples is that omega-6 fatty acids are utilized by the body to send inflammatory signals. So, it’s important to have a balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids (aiming for a 2:1 ratio or better). Some of the aforementioned antinutrients, especially agglutinins, as well as a class of compounds called saponins, especially glycoalkaloids, are most likely to cause inflammation in addition to harming the gut. See The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Nightshades.

- Refined & processed foods. This category is the highest on the “no” list. There’s really no compelling reason to eat processed foods. They are chock-full of inflammatory, addictive compounds and additives. How can we make the best choices when a food has been manipulated to be addictive?! Additionally, these foods are least likely to contain any beneficial nutrients (ever heard of the term “empty calories?”). Processed foods include anything with refined carbohydrates (white/table sugar, wheat flour, etc.) or fats (canola oil, safflower oil, etc.). There’s also many additives that are problematic, such as food dyes, emulsifiers, synthetic flavors, preservatives, etc. See for example Is It Paleo? Guar Gum, Xanthan Gum and Lecithin, Oh My!

- Gut barrier disrupters. Compounds in foods that negatively impact the health of the gut epithelial cells or the junctions in between them can all result in increased intestinal permeability, more colloquially referred to as leaky gut. These include the already mentioned prolamins, agglutinins, digestive enzyme inhibitors, saponins, and alcohol. See Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?), Why Grains Are Bad Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, How Do Grains, Legumes and Dairy Cause a Leaky Gut? Part 2: Saponins and Protease Inhibitors, and The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Alcohol.

- Gut microbiome disrupters. Compounds in grains and legumes as well as alcohol including sugar alcohols are all known to preferentially feed Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli, including toxic strains of E. coli. This is especially problematic in the context of a diet that doesn’t include much vegetable matter. See Why Grains Are Bad Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Alcohol and Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners.

- Carcinogens. Carcinogens are compounds known to promote cancer. When it comes to foods, most of these are due to cooking methods, and consuming a huge amount of veggies is definitely protective. See The Link Between Meat and Cancer.

- Endocrine disrupters. High refined carbohydrate diet, high fructose, and non-nutritive sweeteners can all contribute to insulin resistance (see Is It Paleo? Fructose and Fructose-Based Sweeteners (I’m looking at you, Agave!)) which can then impact many other hormone systems. Hypercaloric diets and fasting can cause leptin resistance, and grazing can negatively impact ghrelin expression (see The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin, The Hormones of Hunger and Is Breakfast Really the Most Important Meal of The Day?), both of which are key regulators of the immune system. Additionally, estrogen-mimicking compounds (such as meat or dairy from animals raised with hormones; phytoestrogens which are naturally occurring and particularly rich in soy and flax; mycoestrogens which come from molds and are a common contaminant in alphalpha; and xenoestrogens come from pesticides, plastics, and detergents) can be found in many foods.

All of these groups go into the “bad” or “no” category. There are some foods that are exclusively bad, but most have at least some nutrition. These are our in-between foods.

What foods are in-between?

What foods are in-between?

The in-between foods tend to raise a lot of questions in the Paleo community: what about the many foods that fall somewhere in the middle? In recent years, the Paleo template has gone beyond a set of rules. Instead, it’s about understanding how a food will affect our gut health, immune health, hormone health, cardiovascular health, neurotransmitter health and detoxificaiton pathways. It’s about understanding which vital nutrients that food will supply our body. It’s about understanding our genetic vulnerabilities; how stress, sleep and activity impact how our bodies react to individual foods; and taking into consideration our health histories and our health goals.

How much bad stuff can be tolerated for the sake of the good stuff in a food? And how much good stuff does there need to be in a food to compensate for the presence of some bad? How do our health histories affect where we draw the line? Is genetic makeup a significant factor? Might some foods be okay if we reserve them for special occasions? And how strict do we need to be in order to mitigate chronic health problems (if we have them)?

Hard and fast answers to these questions are extremely difficult to pinpoint because whether or not these in-between foods work for you will be individual and potentially variable (for example, dairy may work for you normally but in times of stress, you might have a reaction). There are many factors to take into consideration here.

For clarity’s sake, let’s list some of the in-between foods that depend on individual tolerance and needs:

- Dairy (see The Great Dairy Debate and 5 Easy Swaps for Your Favorite Dairy Products)

- Coffee & chocolate (see The Pros and Cons of Coffee)

- Nightshades (What Are Nighshades? and Potatoes: Friend or Foe of Paleo?)

- Eggs (The WHYs Behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Eggs)

- Nuts & seeds (see The WHYs Behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Nuts and Seeds and Nuts and the Paleo Diet: Moderation is Key)

- Corn (see How To Avoid Corn)

- Rice (see What is a Safe Starch?)

- Legumes with and without edible pods (start with Legumes: What Are They?)

- Wine/alcohol (The WHYs Behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Alcohol)

Anyone following an AIP diet will instantly recognize these as the foods that are not included in AIP but might be part of a standard (not very strict) Paleo diet. Why? All of these foods have some immunomodulating compound that can aggravate autoimmune disease.

Some of these foods have not been traditionally thought of as Paleo foods, although writings from amazing thought leaders like Paul Jaminet, PhD and Stephan Guyenet, PhD have challenged some of these assertions. Some have traditionally been considered perfectly sound Paleo choices, although I have been challenging some of those assertions in my writings (I’m looking at you tomatoes!). But, the Paleo community is starting to do something really important: recognizing that for this large collection of in-between foods, whether or not they deserve a Paleo stamp of approval is moot; what really matters is giving you the tools to discover for yourself whether or not these foods work for you. Leaving the Paleo dogma about these in-between foods behind is what hardens the Paleo template to criticism and propells this movment forward to the mainstream.

Now would be a good time to mention that, in my upcoming book Paleo Principles, I’ve separated discussion on diet into three Parts: the “yes” foods, the “no” foods, and the “middle ground” foods. All that comes after a very thorough background on nutrition and biological systems health. I’ve included detailed scientific background on all of the “good” and “bad” stuff in foods discussed in this post (in addition to other considerations). My goal with this new book is to solidify the scientific foundation of the Paleo diet, admitting where the science isn’t cut and dry, and providing the tools you need to adopt and adapt the Paleo diet for yourself.

Now would be a good time to mention that, in my upcoming book Paleo Principles, I’ve separated discussion on diet into three Parts: the “yes” foods, the “no” foods, and the “middle ground” foods. All that comes after a very thorough background on nutrition and biological systems health. I’ve included detailed scientific background on all of the “good” and “bad” stuff in foods discussed in this post (in addition to other considerations). My goal with this new book is to solidify the scientific foundation of the Paleo diet, admitting where the science isn’t cut and dry, and providing the tools you need to adopt and adapt the Paleo diet for yourself.

Making Individual Choices

After several years on the Autoimmune Protocol, I’ve been through many processes of elimination and reintroduction. I’ve been able to test and retest foods and have been fortunate enough to be able to do some food sensitivity testing, as well. This means, in short, that I know myself very well. Knowing our boundaries, our own bodies and our particular health histories is perhaps the most important tool we can use when weighing good foods versus bad.

I’ll argue that foods containing gluten are not health promoting for anyone, but that’s different than saying that no one tolerates gluten. And many other foods avoided on a traditional Paleo diet might be harmless for some individuals (take non-soy legumes, for example: they provide a compelling amount of fiber for healthy gut microbiome and for individuals without gut disbyosis or a disrupted gut barrier, likely won’t cause problems). Once we take the time to eliminate and reintroduce foods, we can begin analyzing grey area foods like the ones listed above.

Elimination simply means avoiding that food completely for about 3 to 4 weeks. After that time, you can “challenge” the food, meaning you consume it in a methodical way and monitor yourself for symptoms for about a week (without reintroducing any other eliminated foods in that time and without doing anything out of your normal routine like traveling). The standard protocol for challenging a food is detailed in Reintroducing Foods after Following the Autoimmune Protocol.

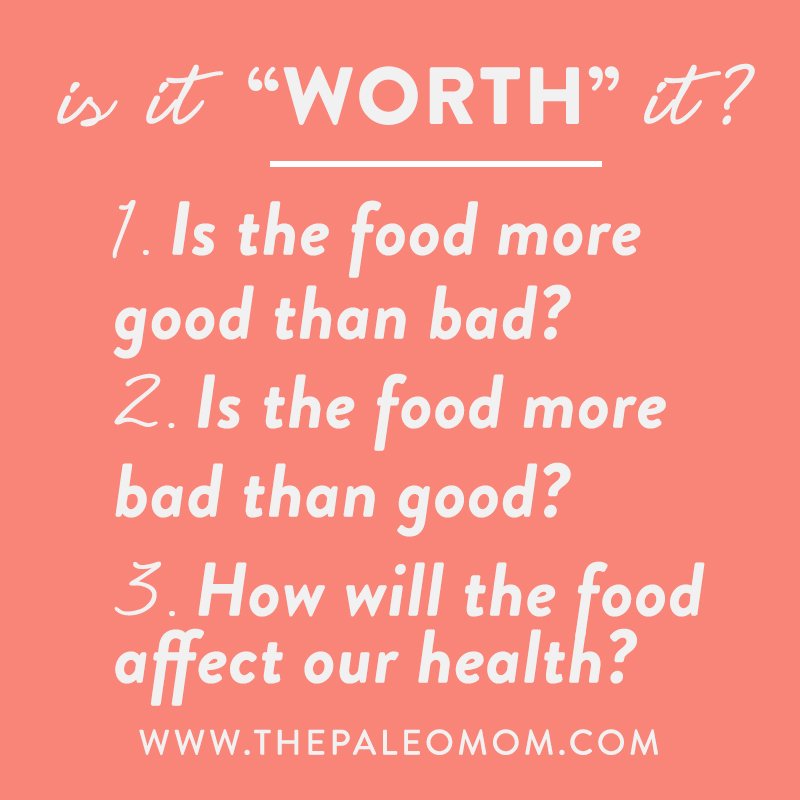

With the knowledge gleaned from eliminating and challenging a food, it’s then much easier to decide what role that food will have in your diet: customary, occasional, or avoided. When you’re deciding whether to eat an in-between food, I think it’s helpful to ask ourselves 3 questions to determine whether a food is “worth it” for us.

With the knowledge gleaned from eliminating and challenging a food, it’s then much easier to decide what role that food will have in your diet: customary, occasional, or avoided. When you’re deciding whether to eat an in-between food, I think it’s helpful to ask ourselves 3 questions to determine whether a food is “worth it” for us.

- Is it more good than bad? (i.e., does it have compelling nutrition to offer?)

- Is it more bad than good? (i.e., what are the chances that problematic compounds will add up over time to undermine my health?)

- How will it affect our health? (i.e., how did I feel when I challenged that food after eliminating it?)

Pretty obvious, right? The simple truth is that I can’t tell you which foods to choose and which to avoid, because it all comes down to your individual health and personal experience with a particular food. I do well with the occasional movie popcorn, but the same food would make my friend Stacy very ill. Popcorn (especially the movie variety, covered in vegetable oil and yellow food dye) is arguably more bad than good. However, it doesn’t effect my health negatively to a degree that is noticeable, so it is, for me, worth the indulgence the one time every couple of months that I go to a movie. See how these three questions allow me to make an informed choice? I want us all to feel empowered when it comes to our food choices, and that often means knowing how to weigh the good against the bad.