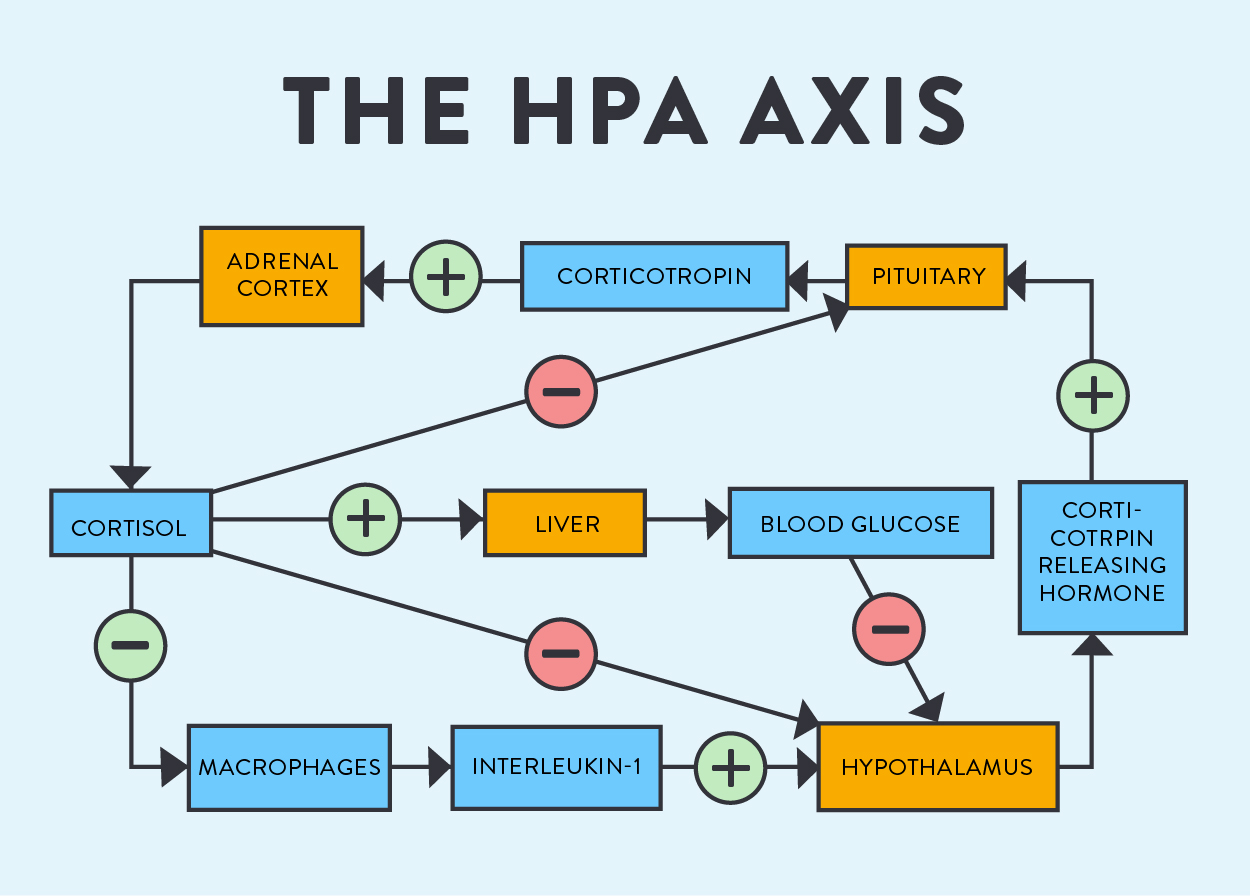

Adrenal fatigue is a condition caused by long-term chronic stress in which the adrenal glands can no longer function adequately(see Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What is Adrenal Fatigue?). Adrenal fatigue can be categorized into three stages. Stage 1 is arguably a common experience of any adult in the modern world, with the symptoms simply being that of normal chronic stress. Easily reversed with shifts in lifestyle (more sleep, stress resilience activities like mindfulness or walking in nature, and actively working to reduce stressors), we are less worried about Stage 1 than the two later stages of this hormone disorder which require testing and more extensive intervention to mitigate. The signs and symptoms of stage 2 and stage 3 adrenal fatigue can be succinctly summarized:

Stage 2: elevated blood sugar, unexplained weight loss or gain, mood swings, low libido, fatigue plus insomnia or feeling “tired and wired”

Stage 2: elevated blood sugar, unexplained weight loss or gain, mood swings, low libido, fatigue plus insomnia or feeling “tired and wired”- Stage 3: extreme exhaustion, frequent illness (cold & flu), slow wound healing

But, adrenal fatigue is not the only disease known to affect the adrenal glands! In this post, we will also go over the other adrenal disorders and conditions affecting other systems in the body that can look very similar to adrenal fatigue. Because understanding exactly how the adrenal glands are malfunctioning is essential for devising a successful treatment protocol with your healthcare provider and because there are several other conditions which can present similarly, testing and proper diagnosis is absolutely the first step in recovering from adrenal fatigue.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

Talking to Your Doctor or Other Practitioner About Adrenal Fatigue

So, we’re find ourselves really tired sometimes. Okay… A lot of the time. When do we need to think about testing for adrenal fatigue? I knew that something was amiss in January 2014 when paying down my sleep debt didn’t alleviate my constant exhaustion, and when my weight started climbing even though my caloric intake was fine and I was sticking to clean Paleo. It was these symptoms that had me seek out a functional/integrative medicine specialist, who diagnosed my stage 3 adrenal fatigue (as well as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis which I had likely had for close to 30 years) and guided my recovery. To be honest, I never even tried bringing up my symptoms with my family doctor, knowing that I wasn’t going to get anywhere.

So, we’re find ourselves really tired sometimes. Okay… A lot of the time. When do we need to think about testing for adrenal fatigue? I knew that something was amiss in January 2014 when paying down my sleep debt didn’t alleviate my constant exhaustion, and when my weight started climbing even though my caloric intake was fine and I was sticking to clean Paleo. It was these symptoms that had me seek out a functional/integrative medicine specialist, who diagnosed my stage 3 adrenal fatigue (as well as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis which I had likely had for close to 30 years) and guided my recovery. To be honest, I never even tried bringing up my symptoms with my family doctor, knowing that I wasn’t going to get anywhere.

Of all the information I have to share about adrenal fatigue, this might be the trickiest part. The bottom line is that many medical practitioners do not recognize adrenal fatigue as a medical condition and consider it to be a very “woo-woo” (read: totally made up) condition. If you believe that you may have adrenal fatigue and have considered other options, I suggest seeking out the help of someone who will be versed in the language of adrenal fatigue AND capable of ordering the lab work required for proper diagnosis. Someone who might be able to help diagnose and treat adrenal fatigue would be a licensed medical doctor (focusing on integrative or functional medicine), osteopathic physician, or naturopathic physician. If you can’t find one near you, consider the functional medicine specialists in ThePaleoMom Consulting who are able to work with clients long-distance.

It’s important to emphasize that there are tried-and-true ways to test for adrenal fatigue to get a good sense of our adrenal gland function. The bottom line is that we can’t dismiss adrenal fatigue if there are testing options that demonstrate its existence (and, as we’ll discuss, there are TONS of ways to measure cortisol output and to match that with adrenal gland stress/functionality) and scientific studies describing it (there are!). Conversely, we can’t diagnose ourselves with this condition without testing (“being tired all the time” isn’t enough!).

One of my goals for this series if to arm us all with some tools to talk about adrenal fatigue. Approaching our doctor and discussing a new onset of exhaustion (or a new pattern of tiredness, like being tired all day and then feeling wired at night) is one step in the process of diagnosing and recovering from the later stages of adrenal fatigue.

Diagnosing Adrenal Fatigue: The Adrenal Stress Index

When it comes to actually diagnosing adrenal fatigue, the gold standard is to utilize a series of salivary samples collected over the course of one day to complete an Adrenal Stress Index. Recall that cortisol is an essential part of our daily circadian rhythm: it helps us wake up in the morning with a spike that peaks at 9PM and slowly drops off throughout the rest of the day (this allows melatonin to act and tell us it’s time to sleep, as in my figure). See Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and why that’s important).

The Adrenal Stress Index (ASI) measures cortisol throughout the day and then maps out how our cortisol varies throughout the day compared to normal values. When someone is in stage 2 or 3 adrenal fatigue, their daily cortisol pattern is different from the normal curve. In stage 2, cortisol is chronically high (this is during the pregnenolone steal phase or resistance phase). This pattern is what creates the “tired and wired” sensation that people in stage 2 often experience; they might be trying to go to sleep but have a huge amount of energy in the evenings due to having too much cortisol (which reduces the amount of melatonin we produce, making it hard for us to fall asleep). In stage 3, cortisol is no longer being produced in (or hardly at all. This is the exhaustion phase), and so the results will indicate a very low curve throughout the day. There can also be intermediary phases between stage 2 and 3 where cortisol is too high in one part of the day but too low at another part of the day.

To complete the test, one needs to take 4-5 salivary samples throughout the day (depending on the exact company used). The samples involve either spitting into a tube or allowing a cotton tube to absorb your saliva for a couple minutes and then placing them in a plastic tube. The samples need to be refrigerated throughout the day, so that’s important to keep in mind when planning what day to complete the test. Likewise, this test needs to be completed on a day without caffeine (though I know the struggle is real!) or exercise (yeah, all the things we do to energize ourselves!), and women with menstrual cycles need to complete it at a certain point (typically between days 19 and 21 of their cycle; because of the intricate relationship between the HPA and HPG cycles, per Part 1). Also, all of the samples are typically taken immediately before a meal and at least 2 hours after eating or drinking anything but water. Some practitioners take the approach of having the samples collected at any time during our cycle and with normal caffeine use, but it’s important to consider that the reference ranges will be less valid with that method.

Getting results back can take a few weeks, so patience is a necessary part of the process. When the results come back, medical practitioners interpret the report and explain the results. It’s also important to retest every few months and adjust your protocols accordingly.

While the ASI provides a major source of information about adrenal gland function, that doesn’t mean that it’s the only method used in the literature or in medical practice.

Other Ways to Measure Cortisol

Cortisol as a molecule is utilized by the body very quickly; it has a half-life, meaning that half of what is excreted has been broken down by the liver to be excreted by the kidneys, of just 90 minutes. So, someone could take measurements of our cortisol, and they would vary approximately every hour and thirty minutes. That is one of the reasons that the Adrenal Stress Index and similar tests are the gold standard for adrenal function! But, there are other methods that are used in conventional medical practices, medical research, and integrative medical practices.

Cortisol Awakening Response is another method of measuring chronic stress and adrenal function that is occasionally used in practice but is more generally seen in research. When we wake up in the morning, there is a huge spike in our cortisol; this phenomenon is very creatively called the cortisol awakening response and is an important part of our sleep-wake cycle (see The New Science of Sleep Wake Cycles (and How To Improve Yours!)). To measure this response, saliva samples (in the same manner as for the ASI) are collected right upon waking up (right in bed!) and then 15 minutes later. There should be some measurable increase in cortisol between samples. If there’s a huge spike (like disproportionately so), that is a rough indicator that the individual has overactive adrenal glands. If there’s a very minimal spike, then the person may have underactive adrenal glands.

Cortisol Awakening Response is another method of measuring chronic stress and adrenal function that is occasionally used in practice but is more generally seen in research. When we wake up in the morning, there is a huge spike in our cortisol; this phenomenon is very creatively called the cortisol awakening response and is an important part of our sleep-wake cycle (see The New Science of Sleep Wake Cycles (and How To Improve Yours!)). To measure this response, saliva samples (in the same manner as for the ASI) are collected right upon waking up (right in bed!) and then 15 minutes later. There should be some measurable increase in cortisol between samples. If there’s a huge spike (like disproportionately so), that is a rough indicator that the individual has overactive adrenal glands. If there’s a very minimal spike, then the person may have underactive adrenal glands.

Importantly, this test can’t be used as a diagnostic, but it has been used in research studies that give us some insight on why adrenal function variation (and thus, chronic stress) is so important.

Serum Cortisol is sometimes measured as a part of standard blood work. Because of the fluctuation of cortisol throughout the day, a single serum sample doesn’t give us a lot of information about adrenal function (other than suggesting to physicians that they should order more tests). Fasting or not doesn’t matter with this sample type, but taking into consideration the time of collection is really important!

Serum Cortisol is sometimes measured as a part of standard blood work. Because of the fluctuation of cortisol throughout the day, a single serum sample doesn’t give us a lot of information about adrenal function (other than suggesting to physicians that they should order more tests). Fasting or not doesn’t matter with this sample type, but taking into consideration the time of collection is really important!

Even though it doesn’t give a complete picture, one of the great benefits of blood samples is that they’re collected in such frequency that we have reference ranges that apply widely to adults and children. For a morning sample (8AM), the reference range is 6-28mg/dL for adults and 3-21mg/dL for children. For a late afternoon sample (4PM), the reference range is 2-12mg/dL for adults and 3-10mg/dL for children. Anything outside of these values might indicate sub-optimal or pathological adrenal function.

24-Hour Urine Collection is based on very similar logic to the Adrenal Stress Index but does not map out cortisol patterns throughout the day. Cortisol that has been conjugated (modified by the liver) is excreted in urine, so urine is a good measure of the cortisol that has been used recently. A 24-hour urine collection is used less simply because of the inconvenience: every single time we use the restroom, we’d have to go into a bucket. As a result, the lab gets all of the conjugated cortisol that we excrete in one day (as a total value rather than a series). A normal value is between 10 and 34mg, though levels can be higher in men. Since this is like an average, someone might have a normal value but abnormal pattern (like low cortisol in the morning and high cortisol at night). A 24-hour urine collection wouldn’t be appropriate for that situation.

24-Hour Urine Collection is based on very similar logic to the Adrenal Stress Index but does not map out cortisol patterns throughout the day. Cortisol that has been conjugated (modified by the liver) is excreted in urine, so urine is a good measure of the cortisol that has been used recently. A 24-hour urine collection is used less simply because of the inconvenience: every single time we use the restroom, we’d have to go into a bucket. As a result, the lab gets all of the conjugated cortisol that we excrete in one day (as a total value rather than a series). A normal value is between 10 and 34mg, though levels can be higher in men. Since this is like an average, someone might have a normal value but abnormal pattern (like low cortisol in the morning and high cortisol at night). A 24-hour urine collection wouldn’t be appropriate for that situation.

Other Adrenal Disorders to Consider

It’s really important to note that stages 2 or 3 of adrenal fatigue might be confused with (or even overlap with!) other adrenal disorders. Namely, hyperadrenalism (or Cushing’s syndrome) or Addison’s disease (also called primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency).

Cushing’s Syndrome is a medical condition in which the adrenal glands produce pathologically high amounts of glucocorticoid hormones (i.e., cortisol and its conjugates) all the time. Cushing’s syndrome, specifically, refers to the clinical symptoms associated with too much cortisol. The syndrome may be the result of many different factors at play. Cushing’s disease itself is most often a result of a tumor in the pituitary gland that produces ACTH. The increased serum cortisol has many effects:

- Hyperglycemia: gluconeogenesis (build up of glucose) and glycogenolysis (breakdown of liver glycogen) pathways are stimulated

- Negative nitrogen balance:

- Salt and water retention: increases blood vessel volume and thus potential to develop hypertension

- Reduced immune response: increases susceptibility to infection by down-regulating macrophage action

As a result of these big physiological changes, there can be other, secondary symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome:

- Central obesity (a focus of adipose tissue around the stomach)

- Myopathy

- Bruising

- Hirsutism (inappropriate hair growth, like around the face in women)

- Acne

- Stretch marks

- Ankle swelling

- Easy fractures

- Missing or changing menstrual periods

If one of more of these symptoms sounds familiar, don’t panic! But keeping them in mind as a complete picture of a disorder is important as we consider all of the ways that the adrenal glands can malfunction and manifest symptom patterns.

How does this compare to the main topic at hand, adrenal fatigue? In short, the symptoms are much worse. Rather than suboptimal function, the adrenal glands are hyperactive in a pathological way, and cortisol levels are likely to be much higher. This generates severe symptoms like hypertension and stretch marks (this is actually the result of tissue breakdown/weakness, because the cortisol keeps the body in the “breakdown” phase rather than the “build up” phase of metabolism).

Addison’s Disease. On the other hand, we have Addison’s Disease. Addison’s is the result of the destruction of the adrenal glands by a variety of mechanisms: autoimmunity, tuberculosis, tumor(s), or an infectious agent (e.g., meningococcus). The consequence is that the hormones exclusively made in the adrenal glands, cortisol and aldosterone, are diminished (or become non-existent if the disease progresses); the other hormones, like the sex hormones, are affected but not eliminated due to their ability to be produced elsewhere. In Addison’s disease, there are an incredible number of symptoms:

Fatigue

Fatigue- Weakness

- Weight loss

- Poor appetite

- Mood changes (apathy, confusion)

- Abdominal pain

- Salt cravings

- Hyperpigmentation

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Weak pulse

- Loss of hair

In comparison to adrenal fatigue and Cushing’s disease, several of the symptoms associated with Addison’s are unique. For example, the hyperpigmentation is associated with an excess production of corticotropin, which increases melanocyte-stimulating hormone to produce more skin pigment (fun fact: President John F. Kennedy was always so tan because of his Addison’s disease). So, someone who is worried about adrenal fatigue may be less concerned about Addison’s, but it’s always good to know the possibilities!

Other Health Problems to Consider

There are other conditions that might be similar to adrenal fatigue in presentation that are worth covering here.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) occurs when a woman’s ovary grows multiple cysts. Scientists are still trying to determine the causes of PCOS, though we know that main causes of cyst development are excess androgens (like testosterone and DHEA) and/or insulin and that PCOS is frequently co-morbid with autoimmune disease. In addition to the hormonal imbalance that is inherently present in this condition, the cysts may release hormones that could cause big changes in the endocrine system, which we know in turn can cause symptoms in almost any organ system of the body. Common symptoms of PCOS include:

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) occurs when a woman’s ovary grows multiple cysts. Scientists are still trying to determine the causes of PCOS, though we know that main causes of cyst development are excess androgens (like testosterone and DHEA) and/or insulin and that PCOS is frequently co-morbid with autoimmune disease. In addition to the hormonal imbalance that is inherently present in this condition, the cysts may release hormones that could cause big changes in the endocrine system, which we know in turn can cause symptoms in almost any organ system of the body. Common symptoms of PCOS include:

- Acne. Hormonal imbalance is one of the most common (and frustrating!) causes of acne. New acne in adulthood is likely a result of hormonal imbalances.

- Hirsutism. This is abnormal hair growth, mostly in “male-type” areas such as the chest and face, that is caused by too much testosterone). Hirsutism is one of the hallmark signs of testosterone dominance, as there are few other issues that would cause this particularly problem.

- Disrupted menses. Women with PCOS almost always have problems with their menstrual periods. This may manifest as missed periods, irregular periods, lengthened periods, and/or extreme PMS.

- Infertility. PCOS can make it very difficult for women to get pregnant. Because of the hormonal changes associated with this syndrome, women trying to get pregnant may not be ovulating and/or producing enough progesterone to sustain a pregnancy.

How does PCOS look or feel like adrenal fatigue? Because both disorders involve dysregulation of the hormonal axes we discussed in Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What is Adrenal Fatigue?, there is considerable overlap in presentation between the two conditions. Examples of the overlap include:

- Insulin resistance

- Unexplained weight gain

- Fatigue

Because of the extent of the overlap, many physicians and practitioners may want to rule it in or out when trying to explain fatigue. PCOS is diagnosed using a combination of medical history, physical exam, ultrasound of the reproductive organs, and blood work. To be diagnosed, a woman must present with two of three of the main symptoms: polycystic ovaries, menstrual dysfunction, or androgen dominance.

Thyroid Disease, in particular Hypothyroidism or Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, may also present as very severe fatigue.

Thyroid Disease, in particular Hypothyroidism or Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, may also present as very severe fatigue.

Hypothyroidism can be caused by either medical treatment (like removal of a nodule or radioactive treatment of goiters) or by inflammation that leads to damage of a part of the thyroid, reducing its ability to make enough thyroid hormone. For this reason, most treatment of thyroid conditions merits taking thyroid hormone (because our body simply does not make it). There are other causes, like a dysfunction in signaling from the pituitary gland, which communicates that thyroid hormone should be released, but these are much more rare. Plus, there are some functional medicine perspectives on suboptimal thyroid function.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (or autoimmune thyroiditis), which I personally have and have discussed before on the blog (in my post Grief Upon Diagnosis: Uncovering Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis), is the main (80-90% of cases) cause of hypothyroidism. Hashimoto’s is an autoimmune condition in which the body attacks and kills thyroid cells. Over time, the thyroid stops being able to produce adequate thyroid hormone, which functionally causes hypothyroidism.

So, how does hypothyroidism look or feel like adrenal fatigue? The commonalities are shocking, once again. Symptoms of hypothyroidism include:

- Fatigue

- Weight gain or difficulty losing weight

- Coarse, dry hair

- Dry skin

- Hair loss

- Cold intolerance

- Muscle cramps

- Constipation

- Depression and irritability

- Memory loss

- Abnormal menstrual cycles

- Decreased libido

Compared to the complexities of some endocrine disorders, hypothyroidism is measured using a simple thyroid panel (that measures free T3, free T4, reverse T3, and TSH [thyroid stimulating hormone]). Including a test for thyroid antibodies is highly recommended (anitobodies against Thyroid Peroxidase [TPO] and thyroglobulin), considering how commonly Hashi’s can be missed without their inclusion in testing due to the overly generous reference ranges for thyroid hormone levels.

How is it possible that we can see so much crossover between these disorders? Once again, it all boils down to the axes that we discussed in Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What is Adrenal Fatigue?. When there is significant dysfunction in one endocrine axis, the entire body is affected. As a result, risk for developing adrenal fatigue, PCOS, hypothyroidism, and blood sugar dysregulation is higher if you have one of these conditions already.

Major Depressive Disorder is another cause of extreme fatigue. Major depressive disorder or MDD is a mental health condition that is very common in the United States and is often under-diagnosed. Part of the reason for that is general misunderstanding of what a depressive episode looks like. A major depressive episode may present as both mood changes and energy changes; this can manifest as sadness, yes, but it can also feel like anxiety, irritability, apathy, and/or general fatigue. Depressive episodes can be sudden in their onset, and a chronic series of episodes could mimic (or run in tandem with) adrenal fatigue crashes. The full list of symptoms of a depressive episode is:

Major Depressive Disorder is another cause of extreme fatigue. Major depressive disorder or MDD is a mental health condition that is very common in the United States and is often under-diagnosed. Part of the reason for that is general misunderstanding of what a depressive episode looks like. A major depressive episode may present as both mood changes and energy changes; this can manifest as sadness, yes, but it can also feel like anxiety, irritability, apathy, and/or general fatigue. Depressive episodes can be sudden in their onset, and a chronic series of episodes could mimic (or run in tandem with) adrenal fatigue crashes. The full list of symptoms of a depressive episode is:

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Impaired concentration or indecisiveness

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Decreased interest in normal activities

- Restlessness

- Significant weight loss or gain

Unlike the other conditions mentioned above, there is no lab test to see if you have depression (though interestingly, there is a link between depression and systemic inflammation, measured by hsCRP). Working with a counselor or talking with a medical practitioner about the specific symptoms you’re experiencing could help with ruling in or out MDD, however.

Sleep Disorders are another explanation for mysterious fatigue, as I discuss in my e-book, Go to Bed. Of everything, this may be the most “obvious” alternative to adrenal fatigue, because lack of sleep is of course going to cause progressive tiredness! We know that sleep should be at the top of everyone’s to-do list just because of how essential it is for health; endocrine health is no exception.

There are many different sleep disorders, and all of them require seeking medical help. If you make it through my 14-Day Go to Bed Challenge and implemented other tips included in the full e-Book and haven’t experienced a significant change in your sleep and fatigue, it may be time to ask your PCP about writing a referral for a sleep specialist.

Conclusions

Clearly, determining whether we have adrenal fatigue and measuring our adrenal gland function is a complicated process that requires a lot of thought and attention to detail on the part of a medical practitioner. Plus, we know that there are several other associated disorders to consider, which makes the need to work with a knowledgeable physician very important. Yet, there are still things that we can do at home to support our adrenal glands (either to prevent adrenal fatigue or to help recover from it), which we will discuss in Part 3 of this series!

Citations

Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Philadelphia, US; Saunders Medical; 2000.

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

Peet A. Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.