Eggs: nutritious, delicious, and… controversial?! Out of all the animal foods out there, eggs are one of the most hotly debated in terms of their health effects on humans. On one hand, they’re a cheap and abundant source of protein, practically synonymous with “breakfast,” and rich in some important nutrients (including choline!). But on the other hand, research has given conflicting messages about the effects of eggs on biomarkers (like blood cholesterol) and disease outcomes (like diabetes and heart disease), leading to more than a little bit of uncertainty about whether we should eat them (and in what quantity!)! In this post, we’ll be cutting through the confusion and looking at what the science actually says.

Eggs: nutritious, delicious, and… controversial?! Out of all the animal foods out there, eggs are one of the most hotly debated in terms of their health effects on humans. On one hand, they’re a cheap and abundant source of protein, practically synonymous with “breakfast,” and rich in some important nutrients (including choline!). But on the other hand, research has given conflicting messages about the effects of eggs on biomarkers (like blood cholesterol) and disease outcomes (like diabetes and heart disease), leading to more than a little bit of uncertainty about whether we should eat them (and in what quantity!)! In this post, we’ll be cutting through the confusion and looking at what the science actually says.

Bird eggs have been part of the human diet since before the dawn of agriculture, and they remain incredibly important across the globe today. Modern-day chickens descended from red junglefowl (native to Southeast Asia) and were domesticated for their meat and eggs sometime before 7500 BCE. By the year 1500 BCE, chickens had been brought to Sumer and Egypt, and they reached Greece in 800 BCE (before then, quail eggs predominated!). Ancient Romans were known to have crushed egg shells in their plates to ward off evil spirits! And though it might be hard to picture life without them now, the first egg carton didn’t appear until 1911, when a man named Joseph Coyle invented a hand-made paper holder to prevent eggs from breaking during shipment (he later went on to design machines to produce the cartons in bulk).

Of course, chickens aren’t the only birds whose eggs are a valuable food source! Duck eggs, quail eggs, and goose eggs can all be found commercially (though sometimes it takes some searching!), and ostrich, turkey, pelican, pheasant, and gull eggs are sometimes eaten as a delicacy (with gull eggs being part of the traditional diet in many indigenous North American cultures, in England, and in Norway). Guinea fowl eggs are abundant at markets in some countries in Africa, as well as elsewhere in the world where they’re farmed (these eggs are much richer than chicken eggs, with a greater yolk-to-white ratio!).

Nutrients in Eggs

Nutritionally, one large chicken egg contains 70 calories, 6.3 grams of protein (including some of every essential amino acid and several non-essential ones), and 5 grams of fat (with about 38% of that fat in the form of saturated fat, 16% coming from polyunsaturated fat, and 46% coming from oleic acid, a monounsaturated fat abundant in olive oil).

Nutritionally, one large chicken egg contains 70 calories, 6.3 grams of protein (including some of every essential amino acid and several non-essential ones), and 5 grams of fat (with about 38% of that fat in the form of saturated fat, 16% coming from polyunsaturated fat, and 46% coming from oleic acid, a monounsaturated fat abundant in olive oil).

The polyunsaturated fat content of eggs varies based on how the hens were fed, with grain-fed chickens having higher levels of omega-6 fats and pasture-raised hens (or hens given omega-3-enriched diets) having higher levels of ALA and DHA. In one study, omega-3 eggs had five times more omega-3 fats as conventional eggs (as well as 39% less of the omega-6 fat arachidonic acid).

A large chicken egg also contains 23% of the DV for selenium, and a significant amount of riboflavin (vitamin B2), cobalamin (vitamin B12), vitamin A, and pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), along with smaller amounts of nearly every other vitamin and mineral other than niacin (vitamin B3) and vitamin K. It also contains 610 mg of choline, a nutrient that behaves similarly to B vitamins and is involved in a huge array of body functions, including memory regulation, fat transport, cell membrane development, muscle control, and neurotransmitter production (it gets converted into acetylcholine). And, free-range eggs in particular have been shown to have higher levels of vitamin D than conventional indoor-raised hens. Pastured eggs have likewise been shown to have twice as much vitamin E and long-chain omega-3 fats, as well as substantially higher vitamin A concentrations, than conventional chicken eggs.

Although all bird eggs are rich in protein and fat, different types of eggs can vary in their nutritional profile. For example, on a gram-per gram-basis, duck eggs are significantly higher in cobalamin (vitamin B12), iron, selenium, thiamine (vitamin B1), and folate (vitamin B9) than chicken eggs, while quail eggs are significantly higher in iron and riboflavin (vitamin B2). And, it’s important to note that the vast majority of an egg’s nutrition is in the yolk! Egg white (also called the albumen) contains some B vitamins and about half of the protein of the egg, but the yolk is where the rest of the good stuff lives.

Reading Egg Carton Labels

Speaking of how eggs vary in nutrition depending on the hen’s diet and living conditions… While in the egg aisle (or while shopping at a farmers’ market), you may have noticed a variety of terms describing different kinds of eggs. As a primer, here’s what to know:

- Conventional eggs: These eggs come from hens kept in small cages, with no ability to roam and no access to the outdoors.

- Organic eggs: These eggs are given organic feed.

- Cage-free eggs: The term “cage free” is regulated by the USDA, and simply means the hens aren’t kept in cages; they’re allowed to “freely roam a building, room, or enclosed area.” However, they don’t have access to the outdoors and can’t roam outside.

- Free-range eggs: Free-range is also a term regulated by the USDA, and means that the hens have some access to the outdoors—though there’s no guarantee how often (if at all) they go outside, and doesn’t ensure their outdoor space is very big.

- Pastured eggs: Although not regulated by the USDA, if an egg carton says pasture-raised and features a “Certified Humane” or “Animal Welfare Approved” stamp, that indicates each egg-laying hen had 108 square feet of outdoor space.

- Omega-3 eggs: Omega-3 eggs come from hens fed diets enriched with flaxseed, algae oil, fish oil, or other omega-3 rich supplements, leading to a higher concentration of omega-3 fats in the yolk.

- Vegetarian fed: Given that chickens are omnivorous, this isn’t necessarily something to strive for, though in the context of conventionally produced eggs, indicates the hens haven’t been fed unhealthy types of animal byproducts.

- Hormone free: This might sound impressive, but hens aren’t typically given steroids or hormones to begin with (they’re banned by the FDA).

Eggs and Human Health

For decades, research has given us conflicting results on the association between eggs and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and other health outcomes. You’ve probably noticed the news headlines flip-flopping between “eggs are safe” and “eggs are as bad as cigarettes”!

The bad news is, even after decades of study, there’s still no crystal clear picture we can paint about how eggs effect humans at different levels of intake and in the context of different health issues. But, when we take into account recent meta-analyses and the clinical trials that have been conducted so far, it does seem that eggs aren’t the dangerous “cholesterol bombs” they were once portrayed as.

A 2021 meta-analysis encompassing 23 studies and over 1.4 million people found that compared to eating no eggs or one egg per day, eating more than one egg per day had no significant association with cardiovascular disease risk. On the contrary, eating more than one egg daily (compared to no eggs or one egg) was linked with a 11% reduced risk of coronary artery disease! A 2016 meta-analysis also found a 12% reduced risk of stroke when comparing the highest egg intake to the lowest (about one egg per day versus less than two per week). Another meta-analysis found that egg consumption was inversely associated with high blood pressure (a 21% reduction between highest and lowest egg intake). And in an analysis stratified by geographical location, there was a negative association between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease risk among Asian cohorts (one study found an 18% lower risk of heart disease death among daily egg consumers and a 28% lower risk of death from a hemorrhagic stroke!).

A 2021 meta-analysis encompassing 23 studies and over 1.4 million people found that compared to eating no eggs or one egg per day, eating more than one egg per day had no significant association with cardiovascular disease risk. On the contrary, eating more than one egg daily (compared to no eggs or one egg) was linked with a 11% reduced risk of coronary artery disease! A 2016 meta-analysis also found a 12% reduced risk of stroke when comparing the highest egg intake to the lowest (about one egg per day versus less than two per week). Another meta-analysis found that egg consumption was inversely associated with high blood pressure (a 21% reduction between highest and lowest egg intake). And in an analysis stratified by geographical location, there was a negative association between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease risk among Asian cohorts (one study found an 18% lower risk of heart disease death among daily egg consumers and a 28% lower risk of death from a hemorrhagic stroke!).

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

On the other hand, a recent overview of 29 different systematic reviews found results that were all over the board. When it came to cardiovascular disease, the results of four relevant meta-analyses contradicted, with some showing increased risk and others, not. The overview showed that, on the whole, eggs were associated with a very slight increased risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal European and Asian women (a 4% increase for women eating 2 to 5 eggs per week versus less than one egg per week), a potentially increased risk of ovarian cancer and GI cancers, and no increased risk for prostate cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Three meta-analyses included in the overview also found a link between egg consumption and increased risk of diabetes (although three others did not), and one meta-analysis showed that more frequent egg consumption was associated with a higher risk of incident heart failure. What to make of these contradictions? This is where clinical trials become really important.

When it comes to clinical trials rather than observational studies, the outlook for eggs has generally been good! A randomized crossover trial in 49 healthy adults found that compared to eating an equivalent amount of oats, eating two eggs daily for six weeks had no negative impact on flow-mediated vasodilation and no effect on total or LDL cholesterol—suggesting that in healthy individuals, eggs don’t harm endothelial function in the short-term. A similar RCT in adults with coronary heart disease found that compared with a high-carbohydrate control breakfast or cholesterol-free egg beaters, eating two eggs daily for six weeks had no adverse effects on flow-mediated dilation, blood lipids, blood pressure, or body weight (so, the results held true in heart disease patients, too!). In a randomized trial of adults with metabolic syndrome, whole egg consumption was also able to improve blood lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity to a greater degree than yolk-free egg substitute, as part of a moderately low-carbohydrate diet. All good news!

A randomized trial using a low-carbohydrate, energy-restricted diet for overweight male adults found that eating three eggs per day, for a total of twelve weeks, didn’t negatively impact blood lipids or blood sugar levels; in fact, it raised HDL “good cholesterol” levels compared to the cholesterol-free egg substitute control group. And in a follow-up to that trial and additional analysis of the follow-up (this time using a low-carbohydrate diet with no restrictions on energy intake), eating three eggs daily for twelve weeks, but not an equivalent amount of cholesterol-free egg substitute, resulted in significant decreases in C-reactive protein and adiponectin, suggesting that eggs were actually beneficial for reducing inflammation while eating a carbohydrate-reduced diet.

A randomized trial using a low-carbohydrate, energy-restricted diet for overweight male adults found that eating three eggs per day, for a total of twelve weeks, didn’t negatively impact blood lipids or blood sugar levels; in fact, it raised HDL “good cholesterol” levels compared to the cholesterol-free egg substitute control group. And in a follow-up to that trial and additional analysis of the follow-up (this time using a low-carbohydrate diet with no restrictions on energy intake), eating three eggs daily for twelve weeks, but not an equivalent amount of cholesterol-free egg substitute, resulted in significant decreases in C-reactive protein and adiponectin, suggesting that eggs were actually beneficial for reducing inflammation while eating a carbohydrate-reduced diet.

Another interesting trial found that when patients with metabolic syndrome ate either three eggs per day or the equivalent amount of choline as a supplement (in a randomized crossover design, with four weeks per arm), there were no changes in any blood lipid measurements or blood sugar, but the egg intervention alone resulted in lower C-reactive protein, insulin, and insulin resistance compared to baseline, while both egg consumption and choline supplementation resulted in lower interleukin-6 (a pro-inflammatory cytokine). This suggests that the choline content of eggs might be behind some of their beneficial effects, but can’t explain them all.

The type of eggs we eat also appear to influence how they impact our health!

In a double-blind crossover trial, people eating five omega-3 enriched eggs per week, for a total of three weeks, saw a 16-18% drop in their triglycerides (with no difference in LDL and HDL cholesterol). Another trial of 19 healthy adults found that eating an extra egg each day for a month, in the form of an omega-3 enriched egg, resulted in higher levels of ApoA1, a lower ApoB/ApoA1 ratio, and lower blood sugar levels—all associated with lower cardiovascular disease and diabetes risk (eating one regular egg daily for the same amount of time didn’t impact blood metrics one way or another). And in a controlled trial of young healthy individuals, eating three omega-3 enriched eggs each day for three weeks significantly decreased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, triglyceride levels, and blood pressure, while increasing post occlusive reactive hyperemia (a measure of endothelial function) compared to baseline measurements (by contrast, the control group eating the same amount of conventional eggs didn’t experience any significant changes).

What About Eggs for Diabetics?

Much of the observational link between egg consumption and heart disease exists specifically among diabetics.

For example, a large prospective cohort study of Korean adults found that after adjusting for confounding variables, egg consumption wasn’t associated with cardiovascular disease incidence on the whole, but it was associated with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetics—those with both diabetes and the highest intake of eggs (an average of 4.2 eggs per week) had a 2.8-fold increase in cardiovascular disease incidence, relative to diabetics with the lowest egg intake. A meta-analysis of 16 studies likewise found that the highest category of egg consumption versus the lowest (at least one egg daily versus less than one per week) wasn’t associated with any increase in overall cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, or stroke, but that among diabetics, there was a 69% increased risk for overall cardiovascular disease. Although scientists aren’t clear on the mechanisms for why the link would be causal, some evidence suggests that diabetic patients (especially those with uncontrolled hyperglycemia) have higher cholesterol synthesis than healthy individuals, possibly making them more sensitive to additional cholesterol (including from eggs) coming through the diet.

So, does this mean diabetics should nix the omelets and scrambles? Not quite! Meta-analyses looking at eggs and diabetes have been difficult to conduct due to differences in study designs, the age of participants, small sample sizes, inconsistent outcome measurement, inconsistent inclusion of diabetics taking insulin, and lack of control for confounding variables, leading to conflicting results. In many studies finding a diabetes-egg consumption link, diabetes was the secondary outcome rather than the primary outcome (meaning it was measured in the analysis, but wasn’t the focus of the study), which could increase the chance that the link was due to residual confounding from variables that weren’t accounted for.

Likewise, clinical trials typically haven’t supported the eggs and diabetes finding that shows up observationally.

Likewise, clinical trials typically haven’t supported the eggs and diabetes finding that shows up observationally.

For example, one randomized controlled trial had 140 patients with type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes eat either a high-egg diet (at least 12 eggs per week) or a protein-matched low-egg diet (less than two eggs per week) for three months, while maintaining their weight (so that weight loss wouldn’t be affecting the results). The study found no difference between the egg groups in terms of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, or glycemic control, but did report that the high-egg group experienced greater satiety and less hunger after breakfast!

The same researchers conducted another trial in diabetics, this one with a three-month weight-loss period and six-month follow-up, again using a 12+ eggs weekly diet versus less than two eggs per week (otherwise matched for macronutrients). The study found no difference in weight loss, blood sugar, glycated hemoglobin, blood lipids, inflammation markers (including C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and soluble E-selectin), adiponectin, or oxidative stress between the high-egg or low-egg diet.

And, a systematic review of six randomized interventions, all involving participants who were either diabetic or at high risk of developing diabetes, found that eating six to 12 eggs per week had no adverse effect on total cholesterol levels, LDL cholesterol, insulin, C-reactive protein, or fasting glucose. Four out of those six studies even showed that higher egg consumption increased HDL levels!

In a randomized trial of type 2 diabetics, eating an energy-restricted high protein diet with two eggs daily, for a total of 12 weeks, resulted in higher HDL levels and higher plasma lutein (a carotenoid antioxidant) compared to an equivalent diet with lean animal protein replacing the eggs. Both diets also reduced total cholesterol, triglycerides, HbA1c, ApoB, fasting insulin, fasting blood sugar, and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Although these changes might be attributed to weight loss itself rather than the composition of the diets, at the very least, eggs didn’t stand in the way of important biomarker improvements.

What’s the Deal With Cholesterol?

What’s the Deal With Cholesterol?

One of the biggest strikes against eggs has long been their cholesterol content—around 200 mg for a single egg. For years, the prevailing belief was that dietary cholesterol consistently impacted blood cholesterol (and in turn, heart disease), but more recent research has called that into question—and added a lot of nuance to the egg discussion, too!

Although the findings of individual trials have been inconsistent, a 2018 meta-analysis of randomized clinical egg trials (RCTs) found that compared to low-egg control diets, egg consumption tends to increase both LDL “bad” and HDL “good” cholesterol (along with total cholesterol), but not impact the total or LDL cholesterol to HDL ratio. Another meta-analysis of egg RCTs noted that egg interventions lasting longer than two months tended to show a larger impact on total and LDL cholesterol compared to trials lasting less than two months, highlighting the potential for frequent egg consumption to have blood lipid effects that only show up on a longer-term basis. Of course, this doesn’t tell us about actual disease outcomes! And surprisingly, among ApoE4 carriers (who are generally considered more sensitive to the effects of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol than the rest of the population), an analysis showed that egg or cholesterol intake had no association with heart disease risk.

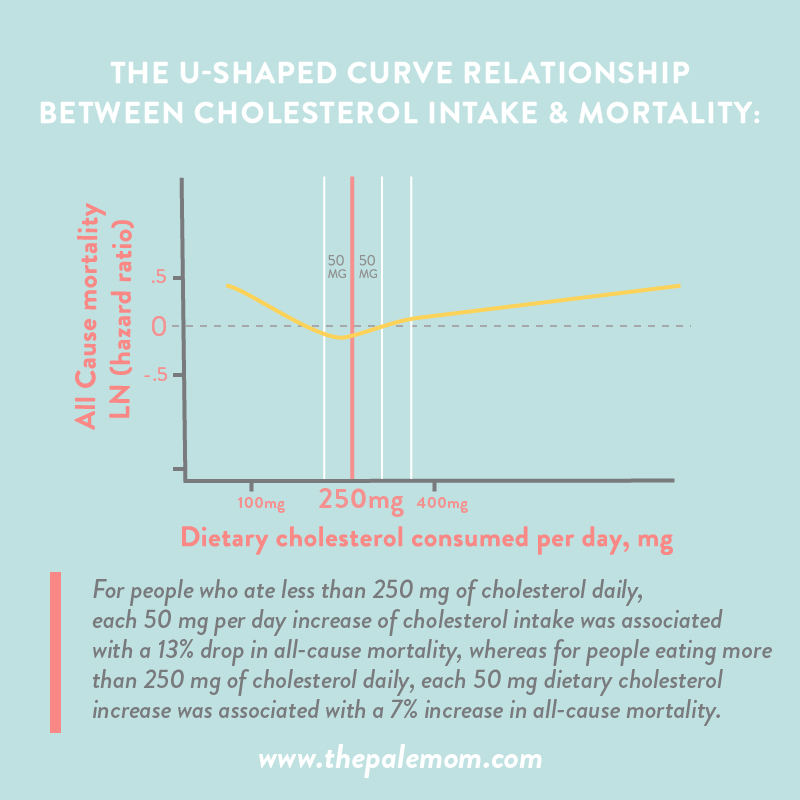

A recent prospective cohort study of over 37,000 adults found no link between dietary cholesterol intake and death from heart disease, or between eggs and heart disease or all-cause mortality. But, it did find a U-shaped curve relationship between cholesterol intake and mortality: for people who ate less than 250 mg of cholesterol daily, each 50 mg per day increase of cholesterol intake was associated with a 13% drop in all-cause mortality, whereas for people eating more than 250 mg of cholesterol daily, each 50 mg dietary cholesterol increase was associated with a 7% increase in all-cause mortality. Because this pattern showed up with dietary cholesterol but not eggs themselves, it’s possible that other components or activities of eggs counteract some of the effects of their cholesterol content (such as by enhancing carotenoid absorption, enhancing HDL function, or delivering lutein and zeaxanthin).

A recent prospective cohort study of over 37,000 adults found no link between dietary cholesterol intake and death from heart disease, or between eggs and heart disease or all-cause mortality. But, it did find a U-shaped curve relationship between cholesterol intake and mortality: for people who ate less than 250 mg of cholesterol daily, each 50 mg per day increase of cholesterol intake was associated with a 13% drop in all-cause mortality, whereas for people eating more than 250 mg of cholesterol daily, each 50 mg dietary cholesterol increase was associated with a 7% increase in all-cause mortality. Because this pattern showed up with dietary cholesterol but not eggs themselves, it’s possible that other components or activities of eggs counteract some of the effects of their cholesterol content (such as by enhancing carotenoid absorption, enhancing HDL function, or delivering lutein and zeaxanthin).

Recent results from a rural cohort study in China also found that BMI and waist circumference modified the effects of egg consumption on lipid profiles, and a recent nationwide Chinese cohort study determined that dietary cholesterol was associated with lower total mortality when it came from eggs, but associated with greater total mortality when it came from non-egg sources!

Certain health conditions may also influence how eggs and their cholesterol impact biomarkers. For example, one double-blind randomized trial of people with high cholesterol or combined hyperlipidemia found that those with combined hyperlipidemia, but not high cholesterol alone, had a significant increase in LDL cholesterol after eating two eggs daily for 12 weeks. Likewise, in a double-blind crossover trial of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, cholesterol supplementation (800 mg per day, the equivalent of about four eggs) raised LDL significantly more among the diabetics than among the healthy controls.

To Egg, or Not To Egg?

In general, eating an egg a day doesn’t appear to increase heart disease risk in the majority of populations, may even have a protective effect against stroke, and isn’t associated with most cancers. There isn’t strong, consistent evidence that a higher intake is harmful, either, though we would need better quality research (including trials spanning a longer length of time) before declaring that for sure. If you have diabetes or other metabolic conditions, it might be worth keeping an eye on blood markers if you decide to make eggs a frequent part of your diet, but even then, the risk isn’t fully clear.

In general, eating an egg a day doesn’t appear to increase heart disease risk in the majority of populations, may even have a protective effect against stroke, and isn’t associated with most cancers. There isn’t strong, consistent evidence that a higher intake is harmful, either, though we would need better quality research (including trials spanning a longer length of time) before declaring that for sure. If you have diabetes or other metabolic conditions, it might be worth keeping an eye on blood markers if you decide to make eggs a frequent part of your diet, but even then, the risk isn’t fully clear.

And, for those of us who can enjoy eggs without problems: the very best eggs are those from local farms that do not supplement the chickens’ diet; chickens are grazers and should feed on insects (so think about it next time you see an egg carton with the phrase “vegetarian diet” on it!!). Your best bet for a really good source of eggs would be your local farmer’s market or even a good friend with backyard chickens! If not, look for local, organic or pasture-raised eggs at your grocery store.

Citations

Alexander DD, et al. “Meta-analysis of Egg Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke.” J Am Coll Nutr. Nov-Dec 2016;35(8):704-716. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2016.1152928. Epub 2016 Oct 6.

Blesso CN, et al. “Whole egg consumption improves lipoprotein profiles and insulin sensitivity to a greater extent than yolk-free egg substitute in individuals with metabolic syndrome.” Metabolism. 2013 Mar;62(3):400-10. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.014. Epub 2012 Sep 27.

Bovet P, et al. “Decrease in blood triglycerides associated with the consumption of eggs of hens fed with food supplemented with fish oil.” Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007 May;17(4):280-7. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.12.010. Epub 2006 Jun 30.

DiBella M, et al. “Choline Intake as Supplement or as a Component of Eggs Increases Plasma Choline and Reduces Interleukin-6 without Modifying Plasma Cholesterol in Participants with Metabolic Syndrome.” Nutrients. 2020 Oct 13;12(10):3120. doi: 10.3390/nu12103120.

Drouin-Chartier J-P, et al. “Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: three large prospective US cohort studies, systematic review, and updated meta-analysis.” BMJ 2020;368:m513.

Fuller NR, et al. “Effect of a high-egg diet on cardiometabolic risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes and Egg (DIABEGG) Study-randomized weight-loss and follow-up phase.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Jun 1;107(6):921-931. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy048.

Fuller NR, et al. “The effect of a high-egg diet on cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes and Egg (DIABEGG) study-a 3-mo randomized controlled trial.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Apr;101(4):705-13. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.096925. Epub 2015 Feb 11.

Jang J, et al. “Longitudinal association between egg consumption and the risk of cardiovascular disease: interaction with type 2 diabetes mellitus.” Nutr Diabetes. 2018 Apr 25;8(1):20. doi: 10.1038/s41387-018-0033-1.

Katz DL, et al. “Egg consumption and endothelial function: a randomized controlled crossover trial.” Int J Cardiol. 2005 Mar 10;99(1):65-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.11.028.

Katz D, et al. “Effects of egg ingestion on endothelial function in adults with coronary artery disease: a randomized, controlled, crossover trial.” Am Heart J. 2015 Jan;169(1):162-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.10.001. Epub 2014 Oct 7.

Knopp RH, et al. “A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of the effects of two eggs per day in moderately hypercholesterolemic and combined hyperlipidemic subjects taught the NCEP step I diet.” J Am Coll Nutr. 1997 Dec;16(6):551-61.

Krittanawong C, et al. “Association Between Egg Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Am J Med. 2021 Jan;134(1):76-83.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.046. Epub 2020 Jul 10.

Kuhn J, et al. “Free-range farming: a natural alternative to produce vitamin D-enriched eggs.” Nutrition. 2014 Apr;30(4):481-4. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.10.002. Epub 2013 Oct 14.

Li M-Y, et al. “Association between Egg Consumption and Cholesterol Concentration: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Nutrients. 2020 Jul 4;12(7):1995. doi: 10.3390/nu12071995.

Liu C, et al. “Association between daily egg intake and lipid profiles in adults from the Henan rural cohort study.” Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 Nov 27;30(12):2171-2179. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.07.004. Epub 2020 Jul 6.

Mazidi M, et al. “Egg Consumption and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality: An Individual-Based Cohort Study and Pooling Prospective Studies on Behalf of the Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group.” J Am Coll Nutr. 2019 Aug;38(6):552-563. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1534620. Epub 2019 Jun 7.

Mutungi G, et al. “Dietary cholesterol from eggs increases plasma HDL cholesterol in overweight men consuming a carbohydrate-restricted diet.” J Nutr. 2008 Feb;138(2):272-6. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.2.272.

Nakamura Y, et al. “Egg consumption, serum total cholesterol concentrations and coronary heart disease incidence: Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study.” Br J Nutr. 2006 Nov;96(5):921-8. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061937.

Ohman M, et al. “Biochemical effects of consumption of eggs containing omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.” Ups J Med Sci. 2008;113(3):315-23. doi: 10.3109/2000-1967-235.

Pearce KL, et al. “Egg consumption as part of an energy-restricted high-protein diet improves blood lipid and blood glucose profiles in individuals with type 2 diabetes.” Br J Nutr. 2011 Feb;105(4):584-92. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003983. Epub 2010 Dec 7.

Ratliff JC, et al. “Eggs modulate the inflammatory response to carbohydrate restricted diets in overweight men.” Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008 Feb 20;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-5-6.

Richard C, et al. “Impact of Egg Consumption on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes and at Risk for Developing Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Nutritional Intervention Studies.” Can J Diabetes. 2017 Aug;41(4):453-463. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.12.002. Epub 2017 Mar 27.

Romano G, et al. “Effects of dietary cholesterol on plasma lipoproteins and their subclasses in IDDM patients.” Diabetologia. 1998 Feb;41(2):193-200. doi: 10.1007/s001250050889.

Rouhani MH, et al. “Effects of Egg Consumption on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials.” J Am Coll Nutr. 2018 Feb;37(2):99-110. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2017.1366878. Epub 2017 Nov 7.

Samman S, et al. “Fatty acid composition of certified organic, conventional and omega-3 eggs.” Food Chemistry 15 Oct 2009;116(4):911-914.

Shin, JY et al. “Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 Jul;98(1):146-59. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.051318. Epub 2013 May 15.

Stupin A, et al. “Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids-enriched hen eggs consumption enhances microvascular reactivity in young healthy individuals.” Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018 Oct;43(10):988-995. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0735. Epub 2018 Apr 10.

Tran NL, et al. “Egg consumption and cardiovascular disease among diabetic individuals: a systematic review of the literature.” Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014 Mar 24;7:121-37. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S58668. eCollection 2014.

Virtanen JK, et al. “Associations of egg and cholesterol intakes with carotid intima-media thickness and risk of incident coronary artery disease according to apolipoprotein E phenotype in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2016 Mar;103(3):895-901. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.122317. Epub 2016 Feb 10.

Wang MX, et al. “Impact of whole egg intake on blood pressure, lipids and lipoproteins in middle-aged and older population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2019 Jul;29(7):653-664. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2019.04.004. Epub 2019 Apr 20.

Xia P-F, et al. “Dietary Intakes of Eggs and Cholesterol in Relation to All-Cause and Heart Disease Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study.” J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 May 18;9(10):e015743. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015743. Epub 2020 May 13.

Zhuang P, et al. “Egg and egg-sourced cholesterol consumption in relation to mortality: Findings from population-based nationwide cohort.” Clin Nutr. 2020 Nov;39(11):3520-3527. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.03.019. Epub 2020 Mar 28.

Zhang X, et al. “Egg consumption and health outcomes: a global evidence mapping based on an overview of systematic reviews.” Ann Transl Med. 2020 Nov;8(21):1343. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-4243.