Throughout the research for my first book, I kept hitting on a recurring theme. Dietary fiber is essential for good health. Yes, I know you’ve heard that it’s important to eat fiber and you probably already understand the value of whole food sources of fiber. You and I probably feel a similar disdain for fiber supplements, fiber-enriched cereals and breakfast bars; there’s even fiber-enriched water! But, as much as the food industry has taken “fiber is good for you” to a much more commercial marketing place than just the stereotypical advice to eat more whole grains, there’s compelling science behind this concept. I’m sure you already understand that there’s just as much fiber in vegetables and fruit for a much lower sugar content and much higher vitamin, mineral and antioxidant content than whole grains, but if you want more information on that topic, see this post.

Yes, fiber is good for us. But through my research, I also kept hitting on pieces of information that went contrary to conventional wisdom (even contrary to conventional Paleo wisdom). Tidbits like insoluble fiber is even more beneficial than soluble (in spite of the fact that the vast majority of studies only evaluate the benefits of soluble fiber). Even more mind-blowing for me was learning that the whole insoluble fiber being abrasive thing is a myth. In fact, the deeper I delved into this subject, the more information I learned that completely challenged everything I thought I knew about this non-essential nutrient. And, the more everything started to make much more sense too.

I have been working on this series of posts for six months and am finally ready to share this information with you (and bust some myths too!). I have broken this immense topic into five posts. Up first:

Part 1: What Is Fiber, Anyway? And Why Is It Good?

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate, meaning that fiber is simply a long string of sugar molecules (saccharides). Fiber comes from the cell walls of plants. In plant cells, it acts as a skeleton and helps to maintain the plants’ shape and structure. There are many, many different types of fiber (different length strings composed of different saccharides, some with branches and some without). The only dietary source of fiber are plant-based foods.

What separates fiber from other carbohydrates (starches and sugars), is that the digestive enzymes produced by our bodies that digest carbohydrates by breaking them down into simple sugars (monosaccharides, which are then absorbed across the intestinal barrier and into the body) are not able to break fiber apart into monosaccharides. Instead, fiber passes through the digestive tract, mainly intact.

Some types of fiber (called fermentable fibers) can be digested by the bacteria that in our intestines (these bacteria mainly reside in the large intestine but there are some in the small intestine too). In fact, fiber serves two main functions in the digestive tract: it adds bulk to stool (this makes it easier to pass) and it feed the probiotic bacteria that live in there (there are many ways that this benefits us). When probiotic bacteria eat fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids—such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. These are extremely beneficial energy sources for the body, including the cells that line the digestive tract and help to maintain a healthy gut barrier. Short-chain fatty acids are also essential for regulating metabolism and they aid in the absorption of minerals, such as calcium, magnesium, copper, zinc, and iron. Healthy gut bacteria have many other important beneficial effects in the body, such as aiding digestion (they release important vitamins and minerals from our food so we can absorb them) and regulating the immune system.

Fiber has other effects, like regulating peristalsis of the intestines (the rhythmic motion of muscles around the intestines that pushes food through the digestive tract), stimulating the release of the suppression of the hunger hormone ghrelin (so you feel more full), slowing down the absorption of simple sugars into the blood stream to regulate blood sugar levels and avoid the excess production of insulin. Fiber also binds to various substances in the digestive tract (like hormones, bile salts, cholesterol and toxins) and depending on the type of fiber, can either facilitate elimination or reabsorption (for the purpose of recycling, which is an important normal function for many substances like bile salts and cholesterol), both of which can be extremely beneficial if not essential for human health.

So, even though fiber doesn’t provide us with energy (like other carbohydrates, fat and protein) and isn’t an essential micronutrient (like vitamins, minerals and phytochemicals), it’s pretty darned important (in fact, one might argue that it’s classification as non-essential is erroneous).

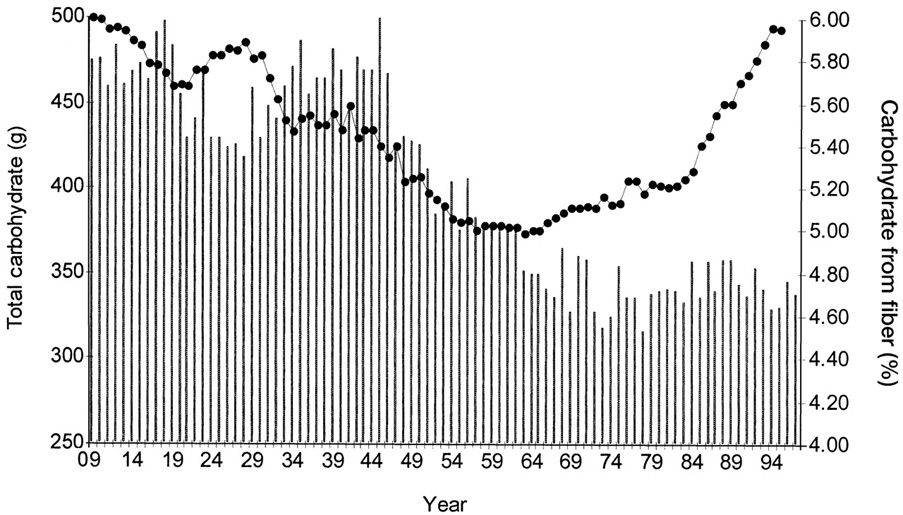

In fact, one of the biggest culprits in the rise of chronic disease seen in the last 50 years is the decrease in fiber consumption relative to total carbohydrates (you know, the part where the carbohydrates we eat are becoming more and more refined, meaning the fiber is stripped out of them).

Take this graph for instance, which I find fascinating. It shows that the current “high carb” consumption in the Standard American Diet isn’t actually that different from a hundred year ago. But how refined those carbohydrates are has changed dramatically. And, during the last 50 years, while the percentage of carbohydrates we consume that come from refined sources has been steadily increasing, so too has been obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, immune diseases alike asthma and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

Certainly, there have been some other important changes in the typical American diet in this time as well. The amount of omega-6 polyunsatruated fats we consume has skyrocketed. The total caloric intake has increased. Our vegetables are less nutrient dense (due to a variety of factors, one of which being that there’s typically a longer period of time between when they are picked and when you buy them and eat them). But, the authors of this paper were able to tease out a very important role for fiber intake, by looking at food availability data (the best measurement we have on what the population as a whole eats) and incidence rates of diabetes over the last 100 years. They found

- dietary fiber is inversely correlated with the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (meaning the lower your fiber intake the higher your risk of developing T2D),

- corn syrup intake (marking refined carbohydrates) is positively correlated with the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (meaning the more corn syrup you consume, the higher your risk of developing T2D), and

- there is no correlation with dietary protein or dietary fat with diabetes incidence once you accounted for total energy intake

The take-home message is that eating whole foods (and therefore avoiding refined carbohydrates) reduces risk of type 2 diabetes. And that it’s much more important that your carbohydrates are coming from whole foods rather than how many grams of them you are eating. Just look at total carbohydrate consumption in the early 1900s versus now… pretty similar, but ten times as many people suffer from type 2 diabetes now compared to 100 years ago.

Diets rich in fiber also reduce the risk of many cancers (especially colorectal cancer, but also liver, pancreas and others) and cardiovascular disease, as well as overall lower inflammation. Prospective studies have confirmed that the higher your intake of fiber, the lower your inflammation (as measured by C-reactive protein). And in fact, a new study showed that the only dietary factor that correlated with incidence of ischemic cardiovascular disease is low fiber intake (and not saturated fat!); and the more fiber you eat, the lower your risk. If you have kidney disease, a high fiber diet reduces your risk of mortality. If you have diabetes, a high fiber diet reduces your risk of mortality. High fiber intake can even reduce your chances of dying from an infection.

Convinced yet?

So, does it matter what types of foods your fiber comes from (and thus what types of fiber you’re eating)? There are an increasing number of studies supporting that the health benefits of high-fiber diets really come from those diets high in vegetables (so vegetable fiber) and, to a lesser extent, fruit and nuts (the health benefits are not experienced when with diets high in cereal grains). These high vegetable diets also reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors and markers of colon cancer risk. How much of this can be directly attributed to the types of fiber in vegetables (mainly insoluble, more on this in Parts 3 and 4 of this series) versus the high vitamin, mineral and phytonutrient content of vegetables compared to other carbohydrate sources remains unknown. Probably, the benefits come from both.

In the next four parts of this series, I will explain the differences between the many different types of fiber (it’s much more complicated than just soluble and insoluble) and get into some details on what types of fiber are the most beneficial (hint: it’s not the party line) and why. But as fun as it’s going to be to delve into these details (and bust some myths!), the take home message is right here:

Eat vegetables. Lots of them.

Burger KN, et al, Dietary fiber, carbohydrate quality and quantity, and mortality risk of individuals with diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43127.

Grooms KN, et al, Dietary Fiber Intake and Cardiometabolic Risks among US Adults, NHANES 1999-2010. Am J Med. 2013 Oct 9. pii: S0002-9343(13)00631-1.

Gross LS, et al, Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: an ecologic assessment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 May;79(5):774-9.

Jenkins DJ, et al, Effect of a very-high-fiber vegetable, fruit, and nut diet on serum lipids and colonic function. Metabolism. 2001 Apr;50(4):494-503.

Jenkins DJ, et al, Effect of a diet high in vegetables, fruit, and nuts on serum lipids. Metabolism. 1997 May;46(5):530-7.

Krishnamurthy VM, et al, High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012 Feb;81(3):300-6.

Norat T, et al, Fruits and Vegetables: Updating the Epidemiologic Evidence for the WCRF/AICR Lifestyle Recommendations for Cancer Prevention. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159:35-50.

Park Y et al, Dietary fiber intake and mortality in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jun 27;171(12):1061-8.

Wallström P, et al Dietary fiber and saturated fat intake associations with cardiovascular disease differ by sex in the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31637.

Yunsheng Ma, et al, Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 April; 83(4): 760–766.

Zhang J, et al Physical activity, diet, and pancreatic cancer: a population-based, case-control study in Minnesota. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(4):457-65.