With mounting research suggesting fructose is a major player in our chronic disease epidemics (see Why is High Fructose Corn Syrup Bad For Us? and Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?), fruit’s health-food status has diminished in some people’s minds (with “safe starches” like sweet potatoes, white potatoes, and even rice gaining a more positive reputation for their low fructose content and resistant starch). The resulting fruit-phobia has caused some of us to trade in (or severely limit) fruit in favor of other carbohydrate sources (or not enough carbs altogether, see How Many Carbs Should We Eat?), all in the name of staying healthier.

With mounting research suggesting fructose is a major player in our chronic disease epidemics (see Why is High Fructose Corn Syrup Bad For Us? and Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?), fruit’s health-food status has diminished in some people’s minds (with “safe starches” like sweet potatoes, white potatoes, and even rice gaining a more positive reputation for their low fructose content and resistant starch). The resulting fruit-phobia has caused some of us to trade in (or severely limit) fruit in favor of other carbohydrate sources (or not enough carbs altogether, see How Many Carbs Should We Eat?), all in the name of staying healthier.

But, the fears surrounding fruit are almost all unfounded! Far from being a fructose bomb, fruit delivers a wide spectrum of micronutrients, phytochemicals, and fiber, making it a uniquely valuable (not to mention delicious!) addition to our diets.

Fruit is Associated with Health Benefits

Although “fruit and vegetables” are often lumped together when talking about the health benefits of plant foods (see The Importance of Vegetables), fruit are independently beneficial! That means that we benefit from adding fruit to our diet even if we’re eating tons of veggies!

Health benefits attributed to specifically fruit include improved gastrointestinal health (including protection from IBS, IBD, diverticular disease, constipation, and colorectal cancer), reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, reduced risk of metabolic syndrome, long-term weight management, protection against lung cancer, improved bone mineral density, reduced asthma severity, reduced risk of depression and other psychological conditions, reduced severity of autism spectrum disorders, reduced risk of seborrheic dermatitis, and reduced severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eating at least 3 servings per day is associated with these health benefits.

The combination of prebiotic fiber, phytochemicals, vitamins and minerals in fruit are behind these wide-ranging benefits.

Fruit Is Far From Empty Calories!

Most of us know that oranges are good source of vitamin C and bananas are loaded with potassium, but that’s just scratching the surface of fruit’s micronutrient bounty! For example, blueberries are rich in vitamin K, manganese, and copper; cantaloupes are sky-high in beta-carotene and vitamin C; pomegranates are great sources of copper, thiamin, and vitamin K; and mangoes have a decent amount of vitamin E, vitamin B6, and potassium.

Each type of fruit has its own micronutrient profile, but generally speaking, fruit is a fantastic source of vitamins and a pretty good source of many minerals.

Fruit Is Full of Phytochemicals

Fruit Is Full of Phytochemicals

A major reason fruit shows up as beneficial in many studies is because it’s teeming with phytochemicals (nonessential compounds that play wide-ranging roles in warding off disease and keeping us healthy). Along with giving fruit (and other plant foods!) their distinctive scents and colors, phytochemicals have the potential to protect against a variety of chronic diseases. (Check out “The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals” and “Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?” for more on these amazing compounds!) Some of the most important phytochemicals in fruit include:

- Anthocyanidins (which give some fruits a blue, purple, or deep red color) have anti-inflammatory, anti-pain, and neuroprotective effects. These are found in blueberries, cranberries, blackberries, plums, red and black grapes, cherries, and raspberries.

- Flavanones have the ability to reduce inflammation, reduce blood lipids, reduce hypertension, exert antioxidant activity, improve insulin sensitivity, and potentially protect against heart disease. And, they’re found abundantly in citrus fruit like oranges, grapefruit, tangerines, and lemons!

- Flavonols (including kaempferol, myricetin, and quercetin) can increase plasma antioxidant capacity, decrease DNA damage in lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell), interrupt the growth of certain cancers, reduce diabetes risk, protect neurons from oxidative damage, and suppress inflammation in the brain. They’re abundant in apples, cherries, and pears.

- Flavan-3-ols help maintain the elasticity of blood vessels (improving blood flow) and potentially reducing our risk of certain cancers and heart disease. They’re found in dark-skinned fruits like elderberries, cranberries, black currants, and grapes, as well as apples, bananas, peaches, pears, and strawberries.

- Tannins act as antioxidants and can reduce blood pressure, protect against harmful microbes, and improve blood lipids. They’re found in pomegranates, persimmons, and berries.

- Lycopene is famous for supporting prostate health and potentially reducing the risk of certain cancers, heart disease, osteoporosis, and diabetes. It’s found in reddish or pinkish fruits like apricots, papaya, watermelon, guava, mango, pink grapefruit, and peaches.

- Lutein and zeaxanthin support eye health (they’re highly concentrated in the retina, and help filter out damaging blue light rays) and can help prevent cataracts and age-related macular degeneration. These phytochemicals are found in kiwi fruit, oranges, grapes, honeydew melons, mangoes, peaches, nectarines, and apples.

- Stilbenes (including resveratrol, rhapontigenin, pterostilbene, and pinosylvin) are powerful antioxidants that can interfere with all stages of cancer development, as well as potentially protect against neurological diseases (including Alzheimer’s), cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Stilbenes are highly concentrated in grape skins, cranberries, and blueberries.

One Word… Fiber!

Have I mentioned lately how awesome fiber is? No? Well, here it is: fiber is fan-freakin’-tastic! Found exclusively in the cell wall of plants, fiber provides bulk to stool (making it easier to pass) and feeds the probiotic bacteria living in our guts. The types of fiber found in fruit can not only promote regularity, but also reduce inflammation, reduce risk of heart disease, improve blood sugar control, slow down the absorption of simple sugars (hence why fruit tends to have a low glycemic load, despite having a relatively high sugar content), bind to substances in the digestive tract (such as bile salts and toxins), protect against colorectal cancer, and help our gut critters flourish and produce beneficial short-chain fatty acids.

More specifically, pectin (which makes up an average of 35% of the cell wall content of fruit fiber) is a potent prebiotic, encouraging the growth of butyrate-producing bacteria belonging to Clostridium cluster XIV and Sutterella (see also The Fiber Manifesto-Part 2 of 5: The Many Types of Fiber and What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?). Likewise, pectin appears to enhance the survival of Lactobacillus (including Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus reuteri) in the stomach and small intestine, boosting its ability to reach the colon. In some cases, such as with unripe bananas and plantains, resistant starch also confers significant prebiotic potential.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Fructose Is Not the Only Sugar in Fruit

Contrary to popular belief, fructose isn’t the only type of sugar in fruit—and in some cases, it’s not even the main sugar in fruit! All fruit contains a mixture of fructose, glucose, and sucrose (which metabolizes into equal parts fructose and glucose in our bodies). And, each type of fruit has a slightly (or significantly) different proportion of these sugars.

For example, papayas, grapes, and most berries are about half fructose and half glucose. Grapefruit is about a quarter fructose and a quarter glucose, with the rest coming from sucrose. And, when we calculate total metabolic fructose (the fructose in the fruit when we eat it, plus the fructose that gets cleaved from sucrose molecules during digestion), we see that most fruit yields roughly equal parts fructose and glucose. Which is great news! While fructose has to get processed in the liver, glucose is used directly by our cells for energy, and doesn’t pose the same metabolic consequences as extremely high fructose intakes (nonalcoholic fatty liver, lipogenesis, and inflammation). Combined with the fact that fresh fruit is bulky (rich in fiber and water) and takes up plenty of stomach space, it’s extremely hard to eat enough fruit to ingest the levels of fructose shown to cause harm in rodent studies and epidemiology. In other words, eating multiple servings of fruit each day is nowhere near comparable to downing fast-digesting HFCS-sweetened sodas, eating packaged foods loaded with fructose-rich sweeteners, and otherwise getting most of our fructose intake from processed foods.

| Fructose | Sucrose | Glucose | |

| Cantaloupe | 21% | 64% | 14% |

| Banana | 40% | 19% | 41% |

| Papaya | 48% | 0% | 52% |

| Mangoes | 22% | 73% | 5% |

| Grapefruit | 26% | 51% | 23% |

| Grapes | 48% | 7% | 45% |

| Apples | 58% | 25% | 17% |

| Apricots | 10% | 64% | 26% |

| Strawberries | 50% | 9% | 41% |

| Blueberries | 50% | 1% | 49% |

| Pineapple | 21% | 61% | 18% |

Can We Eat Too Much Fruit?

Can We Eat Too Much Fruit?

Well, yes, but it takes more than you think. First, high-fructose consumption (in the 75 to 100 grams per day range) is associated obesity, diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease. But, these effects are all exacerbated by co-occurrence of vitamin D deficiency, inactivity, and high fat intake (see also Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm?). Population studies show that fructose consumption (from all sources, including soda) is not associated with obesity below 40 grams daily. It’s unknown how high fructose consumption can be tolerated if we’re only getting it from whole fruit, but there are examples of hunter-gatherers who eat tons of fruit and who are extremely healthy. And, studies show that fruit is definitely not the same as refined sources like high-fructose corn syrup. One recent study that compared the impact on metabolic markers of a high-fructose diet (100 grams daily!), achieved either by eating fruit or high-fructose corn syrup showed that, while both high-fructose diets caused detriments to metabolism compared to the low-fructose diet (<10 grams daily), the high-fructose corn syrup diet was worse than the fruit diet, and the effect was magnified in obese people compared to people who were a healthy weight.

All in all, the scientific evidence supports staying below about 40 grams per day of fructose from all sources. For reference, that translates for 4 to 8 servings of fruit per day, depending on the fruit! (Berries, for example are quite low in fructose, whereas mango is quite high.)

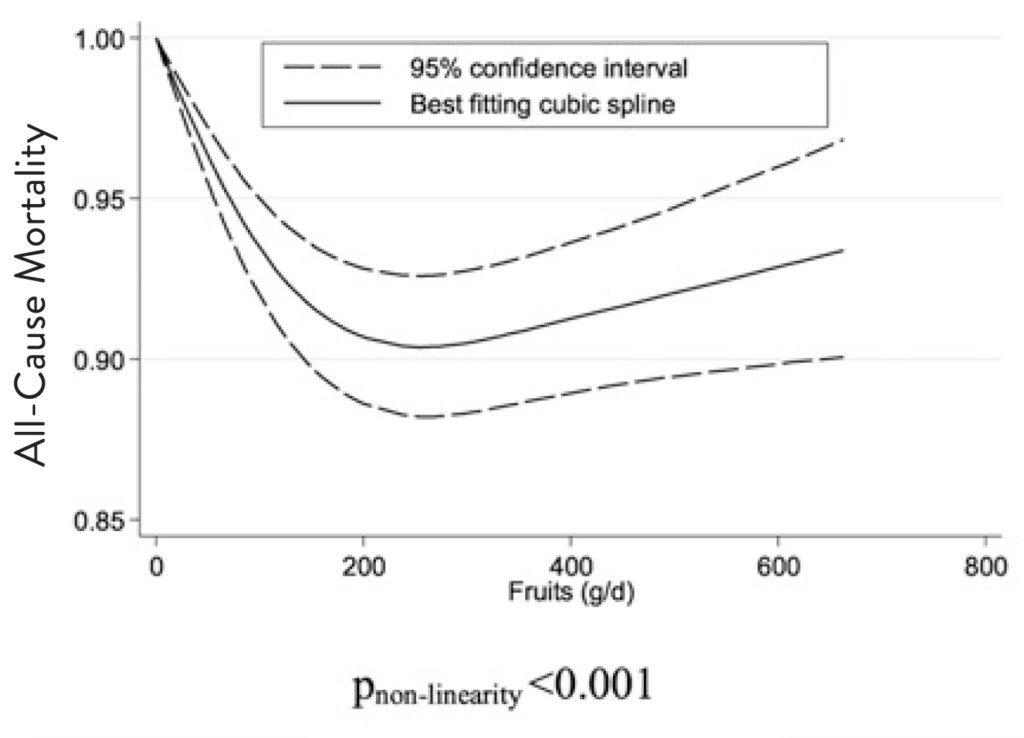

This is confirmed by a 2017 systemic review and meta analysis, which looked at how all-cause morality (a general measure of health and longevity) was impacted by varying intakes of 12 different food groups: whole grains and cereals, refined grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, eggs, dairy products, fish, red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages. This analysis revealed non-linear relationships between how much of a particular food group we eat and how it impacts our health. For example, an egg per day on average had no significant effect on all-cause mortality, but when intake was higher than two eggs per day on average, there was a strong effect and the more eggs eaten, the higher all-cause mortality (an argument for moderate egg consumption and alternate proteins sources for breakfast!). In the case of fruit, increasing fruit consumption daily lowered mortality risk up to about 300 grams of fruit per day (a serving is 80 grams, so this is just under 4 servings) beyond which there was no additional benefit. Intakes over 400 grams per day were not as beneficial as the 300-gram sweet spot, but the good news, even intakes of 600 grams of fruits per day (7.5 servings) was superior to no fruit at all!

This is confirmed by a 2017 systemic review and meta analysis, which looked at how all-cause morality (a general measure of health and longevity) was impacted by varying intakes of 12 different food groups: whole grains and cereals, refined grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, eggs, dairy products, fish, red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages. This analysis revealed non-linear relationships between how much of a particular food group we eat and how it impacts our health. For example, an egg per day on average had no significant effect on all-cause mortality, but when intake was higher than two eggs per day on average, there was a strong effect and the more eggs eaten, the higher all-cause mortality (an argument for moderate egg consumption and alternate proteins sources for breakfast!). In the case of fruit, increasing fruit consumption daily lowered mortality risk up to about 300 grams of fruit per day (a serving is 80 grams, so this is just under 4 servings) beyond which there was no additional benefit. Intakes over 400 grams per day were not as beneficial as the 300-gram sweet spot, but the good news, even intakes of 600 grams of fruits per day (7.5 servings) was superior to no fruit at all!

There’s no reason to avoid fruit on account of it being unhealthy, nutrient-poor, “nature’s candy”, or worthless on the disease protection front. And while we probably don’t want to be eating more than 7 or 8 servings of fruit per day, it’s a fantastic carbohydrate source that deserves more love than it’s been getting lately!

Citations

Aron PM & Kennedy JA. “Flavan-3-ols: nature, occurrence and biological activity.” Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008 Jan;52(1):79-104.

Bavaresco L, et al. “Stilbene compounds: from the grapevine to wine.” Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1999;25(2-3):57-63.

Bertelli A, et al. “Plasma and tissue resveratrol concentrations and pharmacological activity.” Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1998;24:133–8.

Bertram JS. “Carotenoids and gene regulation.” Nutr Rev. 1999;57(6):182-191.

Bishayee A. “Cancer prevention and treatment with resveratrol: from rodent studies to clinical trials.” Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009 May;2(5):409-18.

Burger KN, et al. “Dietary fiber, carbohydrate quality and quantity, and mortality risk of individuals with diabetes mellitus.” PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43127.

Chanet A, et al. “Citrus flavanones: what is their role in cardiovascular protection?” J Agric Food Chem. 2012 Sep 12;60(36):8809-22.

Chang J, et al. “Low-dose pterostilbene, but not resveratrol, is a potent neuromodulator in aging and Alzheimer’s disease.” Neurobiologu of Aging. 2012;33(9):2062-2071.

Chung KT. “Tannins and human health: a review.” Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1998 Aug;38(6):421-64.

Chun OK, et al. “Estimated dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of U.S. adults.” J Nutr. 2007 May;137(5):1244-52.

Dreher ML. Whole Fruits and Fruit Fiber Emerging Health Effects. Nutrients. 2018 Nov 28;10(12):1833. doi: 10.3390/nu10121833.

Gonzalez-Granda A, et al. Changes in Plasma Acylcarnitine and Lysophosphatidylcholine Levels Following a High-Fructose Diet: A Targeted Metabolomics Study in Healthy Women. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1254. Published 2018 Sep 6. doi:10.3390/nu10091254

Grooms KN, et al. “Dietary Fiber Intake and Cardiometabolic Risks among US Adults, NHANES 1999-2010.” Am J Med. 2013 Oct 9. pii: S0002-9343(13)00631-1.

Korte G, et al. “An examination of anthocyanins’ and anthocyanidins’ affinity for cannabinoid receptors.” J Med Food. 2009 Dec;12(6):1407-10.

Krinsky NI, et al. “Biologic mechanisms of the protective role of lutein and zeaxanthin in the eye.” Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:171-201.

Ma L & Lin XM. “Effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on aspects of eye health.” J Sci Food Agric. 2010 Jan 15;90(1):2-12.

Norat T, et al. “Fruits and Vegetables: Updating the Epidemiologic Evidence for the WCRF/AICR Lifestyle Recommendations for Cancer Prevention.” Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159:35-50.

Pari L & Satheesh A. “Effect of pterostilbene on hepatic key enzymes of glucose metabolism in streptozotocin-and nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats.” Life Sciences. 2006;79(7):641-645.

Schwingshackl L, et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jun;105(6):1462-1473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153148.

Sommerburg O, et al. “Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes.” Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Aug;82(8):907-10.

Ververidis F, et al. “Biotechnology of flavonoids and other phenylpropanoid-derived natural products. Part I: Chemical diversity, impacts on plant biology and human health.” Biotechnol J. 2007 Oct;2(10):1214-34.

Williamson G & Manach C. “Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. II. Review of 93 intervention studies.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:243S-255S.

Yamaguti-Sasaki E, et al. “Antioxidant capacity and in vitro prevention of dental plaque formation by extracts and condensed tannins of Paullinia cupana.” Molecules. 2007 Aug 20;12(8):1950-63.