For those of us with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, it is critical to understand the concept of gluten cross-reactivity. How many of us is that? Well, 98% of all celiac disease sufferers have one of two variants of the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) gene, either DQ2 or DQ8. Celiac disease sufferers also produce exaggerated amounts of a protein called zonulin in response to gluten consumption. Zonulin is a protein that controls the formation of the tight junctions between enterocytes, and when there is increased zonulin, those junctions open up, causing a leaky gut. There’s some evidence that this dysfunctionally high zonulin production is a consequence of having either HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8; for example, high zonulin production in response to gluten consumption is also seen in people without celiac disease but with IBS who have HLA-DQ2. This link has led many experts to suggest that everyone with one of these two HLA variants (about 55 percent of the general population) should adopt a gluten-free diet.

Gluten cross-reactivity is of particular concern for anyone whose body produces antibodies against gluten, technically a gluten allergy or gluten intolerance. Essentially, when your body creates antibodies against gluten, those same antibodies also recognize proteins in other foods. When you eat those foods, even though they don’t contain gluten, your body reacts as though they do. You can do a fantastic job of remaining completely gluten-free but still suffer all of the symptoms of gluten consumption—because your body still thinks you are eating gluten. This is a very important piece of information that I was missing until recently.

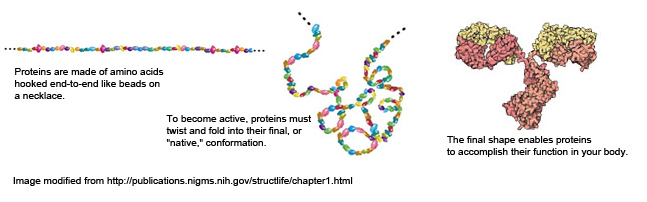

Proteins are made of long chains of amino acids (small proteins may only be 50 amino acids long whereas large proteins may be 2000 amino acids long) and it is the specific sequence of these amino acids that determines what kind of protein is formed. These amino acid chains are folded, kinked and buckled in extremely complex ways, which gives a protein its ‘structure’. This folding/structure is integral to the function of the protein.

An antibody is a Y shaped protein produced by immune cells in your body. Each tip of the Y contains the region of the antibody (called the paratope) that can bind to a specific sequence of amino acids (called the epitope) that are a part of the protein that the antibody recognizes/binds to (called the antigen). The classic analogy is that the antibody is like a lock and a 15-20 amino acid section of a protein/antigen is the key. There are 5 classes (or isotypes) of antibodies, each with distinctive functions in the body. The IgE class of antibodies are responsible for allergic reactions; for example, when someone goes into anaphylaxis after eating shellfish. The two classes IgG and IgA are critical for protecting us from invading pathogens but are also responsible for food sensitivities/intolerances. Both IgA and IgG antibodies are secreted by immune cells into the circulation, lymph, various fluids of the body (like saliva!) and tissues themselves. And both IgG and IgA antibodies are found in high concentrations in the tissues and fluids surrounding the gut (this is part of why the gut is considered our primary defense against infection).

The formation of antibodies against an antigen (whether this is an invading pathogen or a food) is an extremely complex process. When antibodies are being formed against a protein, the antibodies recognize specific (and short) sequences of amino acids in that protein. Depending on how the antigenic protein is folded, certain amino acid sequences in that protein are more likely to be the target of new antibody formation than others, simply because of the location of that sequence in the structure of the protein. Certain sequences of amino acids are more antigenic than others as well (i.e., more likely to stimulate antibody formation). This is also part of why certain foods have a higher potential to cause allergies and sensitivities.

Understanding that antibodies recognize short sequences of amino acids and not an entire protein is key to understanding the concept of cross-reactivity (and molecular mimicry, but that’s a topic for another post). It also is the reason why many different antibodies can be formed against one protein (this redundancy is important for protecting us from pathogens). Many different antibodies can also be formed against one pathogen or, more relevant to this discussion, one specific food.

Understanding that antibodies recognize short sequences of amino acids and not an entire protein is key to understanding the concept of cross-reactivity (and molecular mimicry, but that’s a topic for another post). It also is the reason why many different antibodies can be formed against one protein (this redundancy is important for protecting us from pathogens). Many different antibodies can also be formed against one pathogen or, more relevant to this discussion, one specific food.

So what happens in cross-reactivity? In this case the amino acid sequence that an antibody recognizes is also present in another protein from another food (in the case of molecular mimicry, that sequence is also present is a protein in the human body). There are only 20 different amino acids, so while there are millions of possible ways to link various amount of each amino acid together to form a protein, there are certain amino acid sequences that do tend to repeat in biology.

The take home message: depending on exactly what antibody or antibodies your body forms against gluten, it/they may or may not cross-react with other foods. So, not only are you sensitive to gluten, but your body now recognizes non-gluten containing foods as one and the same. Who needs to worry about this? Any of the estimated 20% of people who are gluten intolerant or have celiac disease, i.e., have formed antibodies against gluten.

A recent study evaluated the potential cross-reactivity of 24 food antigens. These included:

- Rye

- Barley

- Spelt

- Polish Wheat

- Oats (2 different cultivars)

- Buckwheat

- Sorghum

- Millet

- Amaranth

- Quinoa

- Corn

- Rice

- Potato

- Hemp

- Teff

- Soy

- Milk (Alpha-Casein, Beta-Casein, Casomorphin, Butyrophilin, Whey Protein and whole milk)

- Chocolate

- Yeast

- Coffee (instant, latte, espresso, imported)

- Sesame

- Tapioca (a.k.a. cassava or yucca)

- Eggs

They did not find cross-reactivity with all of these foods (as is implied by the Cyrex Labs gluten cross-reactivity blood test, a.k.a. Array 4). But, they did find that their anti-gliadin antibodies (antibodies that recognize the protein fraction of gluten, and they used two different types [monoclonal and polyclonal] antibodies for their tests which yielded results consistent with each other) did cross-react with all dairy including whole milk and isolated dairy proteins (casein, casomorphin, butyrophilin, and whey)—this may explain the high frequency of dairy sensitivities in celiac patients—oats (but only one cultivar), brewer/baker’s yeast, instant coffee (but not fresh coffee), milk chocolate (attributable to the dairy proteins in chocolate), millet, soy, corn, rice and potato.

Save 70% Off the AIP Lecture Series!

Learn everything you need to know about the Autoimmune Protocol to regain your health!

I am loving this AIP course and all the information I am receiving. The amount of work you have put into this is amazing and greatly, GREATLY, appreciated. Thank you so much. Taking this course gives me the knowledge I need to understand why my body is doing what it is doing and reinforces my determination to continue along this dietary path to heal it. Invaluable!

Carmen Maier

This is one of the figures from the paper. I’ve added a green line to show you the level of the negative control, meaning below which there is no gluten-cross reactivity. And, I’ve highlighted all the positives in yellow, meaning those foods are potentially cross-reactive with gluten antibodies.

It’s important to emphasize that not all people with gluten sensitivity will also be sensitive to all of these potential gluten cross-reactors. The second bar from the left, α-gliadin, is the positive control, basically showing that the antibodies against gluten that they used for these experiments do indeed bind to gluten. Note that all other positives are less than α-gliadin, meaning the reaction is weaker. Soy and potatoes are notably quite weak reactions, while dairy is notably quite high (especially considering that there’s four different proteins in dairy that react with the gluten antibodies).

While not all people with gluten sensitivities will also be sensitive to all of these foods, they should be highlighted as high risk for stimulating the immune system. Just like trace amounts of gluten can cause a reaction in at least those with celiac disease (the threshold for a reaction has not been tested in non-celiac gluten sensitivity), even a small amount of these foods can perpetuate inflammation and immune responses. This is important when you think of the small amounts of corn used in so many foods and even the trace milk proteins that can be found in ghee.

The foods to be wary of, if you have gluten-sensitivity, are:

- dairy

- oats

- yeast (brewer’s, baker’s, nutritional)

- instant coffee

- milk chocolate

- millet

- soy

- corn

- rice

- potato

Beyond this, gluten contamination is common in the food supply and many grains and flours that are inherently gluten free may still contain gluten once processed. Commonly contaminated grain products include millet, white rice flour, buckwheat flour, sorghum flour, and soy flour. As these are commonly used ingredients in commercial gluten-free baked goods, extreme caution should be exercised.

Cyrex Labs offers a simple blood test that is referred to as their gluten ross-reactivity panel, a.k.a. Array 4. It tests for reactions to the gluten cross-reactors mentioned above as well as the non cross-reactors evaluated in the paper. Cyrex Labs reported to me in personal communication that they see positive sensitivities frequently (many as high as 25%) in many of those foods in people with diagnosed gluten sensitivity. This may reflect that when you have a leaky gut, food intolerances are quite easy to form.

If you have autoimmune disease (which has a very high correlation with gluten-sensitivity), celiac disease, gluten-sensitivity, or are simply not seeing the improvements you were hoping for by following a standard Paleo diet, one or all of these foods may be the culprit. You have the choice of either cutting these foods out of your diet and seeing if you improve or get tested to see if your body produces antibodies against these foods.

Citations

A great overview of proteins and antibodies (and source of protein folding image): http://publications.nigms.nih.gov/structlife/chapter1.html

A fairly technical review of food IgG-mediated food sensitivities: http://www.usbiotek.com/Downloads/information/criticalReview.pdf

Cyrex Labs Array 4: http://www.cyrexlabs.com/CyrexTestsArrays/tabid/136/Default.aspx

Image of antibody binding taken from http://classes.midlandstech.edu/carterp/Courses/bio225/chap17/ss2.htm

A. Vojdani and I. Tarash, “Cross–Reaction between Gliadin and Different Food and Tissue Antigens,” Food and Nutrition Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2013, pp. 20-32. http://www.scirp.org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=26626

Thompson T et al. Gluten contamination of grains, seeds, and flours in the United States: a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Jun;110(6):937-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.014.

Cecilcio LA, et al. The prevalence of HLA DQ2 and HLA DQ8 in patients with celiac disease, in family and in the general population, Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015 Jul-Sep; 28(3): 183–185.