There are many resources, even within the Paleosphere, that make claims about weight loss (a lot of which are based more on the theoretical rather than substantiated by scientific and/or clinical knowledge! Always check resources being used!); and the huge number of dramatic success stories out there (admittedly, like my own) tend to lend credence to these claims. Certainly, there is growing clinical data to support the Paleo diet as a strategy for healthy weight loss (see Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies). However, there are no guarantees, especially with the growing diversity of implementation approaches to Paleo eating (not all approaches support weight loss), the increasing availability of prepackaged goods (including many hyperpalatable, calorie-dense options), and the encroachment of other dietary strategies that aren’t necessarily supportive of weight loss efforts, not to mention the complexity of weight loss and weight loss maintenance itself! But, if a desire to lose weight has brought you to Paleo, rest assured, you’re in the right place. It’s just a little more complicated than following lists of “eat this” and “don’t eat that” and “eat until you’re full” (for parts 2 and 3 of this series, see Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 2: Lifestyle Choices That Make a Difference and Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 3: Troubleshooting Weight Loss Difficulties).

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

Building on the standard Paleo framework, we can utilize an evidence-based approach for long-term weight loss success by making some simple adjustments to the standard Paleo diet (most of which boils down to simply paying attention to details) and incorporating lifestyle changes to support our bodies through the metabolic release of fat. How do we manipulate the Paleo way of life to meet our weight loss needs? We need to think about weight loss in terms of trying to meet these three goals:

- Establish a caloric deficit

- Reduce/eliminate systemic inflammation

- Support biochemical pathways of fat and glucose metabolism

If we can achieve these goals, we are preparing our bodies for the metabolic and other physiological necessities (like hormonal changes, etc.) that we must go through in order to lose weight in the form of fat (and not just water retention, etc.). Every aspect of the nutrition and lifestyle recommendations here is aimed at modifying physiology to support the above goals – that includes things like sleeping more, opting for omega-3 fatty acids, and starting to think about the details of nutrition!

Paleo Basics

Before we get into the specifics, I wanted to review basics of the Paleo diet for anyone who might be new to this approach. Its foundation is the most nutrient-dense foods available to us, including organ meat, seafood, and both huge variety and copious quantities of vegetables, with other quality meats, fruit, eggs, nuts, seeds, healthy fats, probiotic and fermented foods, herbs and spices to round it out. At the same time, it omits foods known to be inflammatory, disrupt hormones, or negatively impact the health of the gut, including all grains, most legumes, conventional dairy products, and all processed and refined foods. Believe it or not, ALL of these foods are ones that can hinder weight loss, because systemic inflammation is associated with weight problems (we will discuss the mechanism of this later).

At its core, the Paleo diet is a plant-based diet, with two thirds or more of our plate covered with plant foods and only one third with animal foods. Of course, meat consumption is enthusiastically endorsed as well because it provides vital nutrients not obtainable from plant sources (if you’re questioning whether meat is a good choice for you, check out The Link Between Meat and Cancer). Sourcing the highest quality food we can is encouraged, meaning choosing grass-fed or pasture-raised meat, wild-caught seafood, and local in-season organic fruits and vegetables whenever possible.

One of the reasons that the Paleo diet is so successful is that it isn’t a diet at all: it’s a way of life, within which there is a relatively flexibly set of guidelines, all of which are determined by scientific evidence. There are no hard and fast rules about when to eat, how much protein versus fat versus carbohydrates to eat (but see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers), and there’s even some foods (like high quality dairy, white rice and potatoes) that some people choose to include in their diets, whereas others do not. This means that’s there’s room to experiment so you can figure out not just what makes you healthiest but also what makes you happiest and fits into your schedule and budget.

One of the reasons that the Paleo diet is so successful is that it isn’t a diet at all: it’s a way of life, within which there is a relatively flexibly set of guidelines, all of which are determined by scientific evidence. There are no hard and fast rules about when to eat, how much protein versus fat versus carbohydrates to eat (but see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers), and there’s even some foods (like high quality dairy, white rice and potatoes) that some people choose to include in their diets, whereas others do not. This means that’s there’s room to experiment so you can figure out not just what makes you healthiest but also what makes you happiest and fits into your schedule and budget.

While I enthusiastically endorse this lifestyle, there are some caveats to keep in mind when it comes to utilizing or modifying the Paleo diet for weight loss or weight maintenance. The first is simple: we can’t ignore the laws of thermodynamics.

We Can’t Ignore Calories!

One of the long-term trends in the Paleo movement has been to claim that when we eat a Paleo diet, calories no longer matter (we hear similar claims from low-carb dieters too). While I love the faith that people place into this lifestyle, the bottom line is that we cannot ignore the role that calories and caloric density play in the way that ALL eating relates to weight loss: portion control that creates an energy deficit is the only way that we lose weight (see Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet). As I said before, we can’t ignore the thousands of scientific articles and the laws of physics when it comes to weight loss.

One of the long-term trends in the Paleo movement has been to claim that when we eat a Paleo diet, calories no longer matter (we hear similar claims from low-carb dieters too). While I love the faith that people place into this lifestyle, the bottom line is that we cannot ignore the role that calories and caloric density play in the way that ALL eating relates to weight loss: portion control that creates an energy deficit is the only way that we lose weight (see Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet). As I said before, we can’t ignore the thousands of scientific articles and the laws of physics when it comes to weight loss.

Okay, that doesn’t sound very glamorous and you might associate the concept of portion control with some pretty negative things, like deprivation, calorie counting, and feeling hungry. But, portion control doesn’t automatically imply “dieting” (in fact, I’d never suggest “going on a diet” anyways, because it’s well-demonstrated in the scientific literature that diets don’t work for long-term weight loss!). What it means is that, whether conscientious or the natural result of a diet’s structure, the amount of energy in the food we eat is controlled. Typically, that implies that we’re consuming fewer calories than we’re burning, also called an energy deficit, which is permissive for weight loss.

I’m going to say it once more: we cannot lose weight unless we are in a calorie deficit. This isn’t the only factor that contributes to weight loss, but it is an absolute requirement before we can shed excess fat.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

The fact is that portion control works. In fact, portion control is the driving force behind virtually every successful weight-loss diet (whether it be low-carb, Paleo, the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, Weight Watchers or any number of short-lived fads). No matter what a diet’s official rationale is, when it induces weight loss, it does so chiefly by reducing the number of calories consumed. Different diets go about doing this in different ways, but energy intake (which translates to portion size) is what ultimately ends up changing the numbers on the scale!

But, just because weight loss boils down to calorie intake versus expenditure doesn’t mean that all diets are created equal when it comes to portion control! Many modern processed foods (particularly ones rich in refined carbohydrate, vegetable oils, salt, and sugar, and low in protein) are designed specifically to induce over-eating and override our satiety signals, especially when compared to whole foods closer to their natural state. For decades, rodent experiments have shown that energy dense diets (high in fat, refined carbohydrate, and total calories) result in overeating and obesity relative to lower-energy-density diets. In fact, an interesting study from 2014 found that energy-dense food (equivalent to potato chips) strongly activated the reward system of rats’ brains, leading to something called hedonic hyperphagia (eating for pleasure rather than to fulfill energy needs). This effect was not seen when the rats ate fat or carbohydrate separately! A similar phenomenon occurs in humans under the same conditions.

Not surprisingly, food manufacturers have capitalized on the well-known effect of energy density on eating behavior to create products that we want to keep eating, even when we aren’t really hungry (think of the Lay’s potato chip slogan, “Bet you can’t eat just one!”). This is part of why foods like pastries, cookies, chips, pizza, and other dense combinations of fat and carbohydrate are so strongly linked with obesity across the globe: they’re harder to stop eating when we’re full. And, it helps explain why diets that eliminate high-fat, high-carb, energy-dense foods tend to result in a spontaneous reduction of energy intake (and thus weight loss). This applies to the entire spectrum of low-carb diets, Paleo, the Mediterranean diet, low fat plant-based diets… on and on!

Not surprisingly, food manufacturers have capitalized on the well-known effect of energy density on eating behavior to create products that we want to keep eating, even when we aren’t really hungry (think of the Lay’s potato chip slogan, “Bet you can’t eat just one!”). This is part of why foods like pastries, cookies, chips, pizza, and other dense combinations of fat and carbohydrate are so strongly linked with obesity across the globe: they’re harder to stop eating when we’re full. And, it helps explain why diets that eliminate high-fat, high-carb, energy-dense foods tend to result in a spontaneous reduction of energy intake (and thus weight loss). This applies to the entire spectrum of low-carb diets, Paleo, the Mediterranean diet, low fat plant-based diets… on and on!

Here’s where Paleo has a huge leg up over many other diets! Because a well-designed Paleo diet will be loaded with fibrous plant foods (think: dark leafy greens, seaweeds, tubers, fermented vegetables, berries, and a huge spectrum of colorful veggies) alongside highly-satiating quality meats (think: organ meat, grass-fed beef, pasture-raised pork and poultry, fish and shellfish), the energy density will naturally be much lower than the Standard American Diet, and we’ll be getting fewer calories (but more micronutrients!) per bite. Plus, some evidence suggests that certain vitamins and minerals help regulate appetite, so a Paleo diet might also assist with weight loss by increasing our micronutrient intake. (See The Importance of Nutrient Density) This concept is supported by real scientific evidence. There are studies specifically examining a Paleolithic diet for weight loss, pitting it against other diets (see Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies). It’s been demonstrated that transitioning to a Paleolithic-style diet results in a spontaneous reduction of calories by about 400 kilocalories per day – that’s almost a pound of weight loss per week, and without any additional focus or attention paid to weight loss! Furthermore, research has demonstrated that a Paleo diet improves the symptoms of metabolic syndrome, blood lipids, and fasting blood sugar, all of which may hinder weight loss efforts due to the hormonal imbalances underlying these issues.

Generally, someone adopting a Paleo diet with weight to lose can expect to achieve a modest caloric deficit, without feeling deprived, counting calories, or going hungry–just because of replacing addictive empty calories with satiating nutrient-dense whole foods. Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean that every overweight person following a Paleo diet will spontaneously achieve a caloric deficit and watch the pounds melt away. There are plenty of potential pitfalls, like overindulging in nuts, underfocus on veggies, overfocus on fats, or relying on Paleo adaptations of SAD foods like Paleo breads, muffins, and cookies. And, at least anecdotally, it seems as though people with a history of food addiction and/or binge eating disorder (yes, this includes me) struggle more than others to moderate total caloric intake even within the Paleo framework. One strategy to combat this is to combine Paleo principles with some good old fashioned measuring of portions and tracking of calories. This can be a great short-term strategy to help educate ourselves on the best composition of our Paleo plates. Is it fun? No. Effective? You betcha. Sustainable? Generally not. Fortunately for us, there’s other strategies we can use to focus of food choices on options that are more satiating per calorie as well as utilize additional information from scientific studies to get back to eating more intuitively while achieving and sustaining our weight loss goals.

#threequartersveggies: Focus on Vegetables First!

My love of vegetables is no secret (I did start the above hashtag, after all). That’s right, I think every plate should be three quarter vegetables (we’ll talk about what should be on the rest our plates in a just a few!). In fact, I think the approach of ADDING more vegetables has just as much merit as removing other foods from our Paleo plate or making other changes to our diet. In all likelihood, vegetable consumption can make or break a weight loss effort.

New research in the field of obesity is helping us to elucidate the difference between normal weight and overweight people. Successful weight loss is highly related with vegetable intake, which is no surprise for many reasons. One of the differences is the way that we approach vegetable (and fruit) intake. People with obesity/overweight are more likely to consume plants when they have better planning (something we all know is necessary when it comes to Paleo!) and inhibitory control (being able to resist highly palatable foods). Making the choice to incorporate more vegetables into our diet is one way to retrain our executive functioning, allowing us to promote weight loss and make it more sustainable in the long term.

Relative caloric & micronutrient density

Relative caloric & micronutrient density

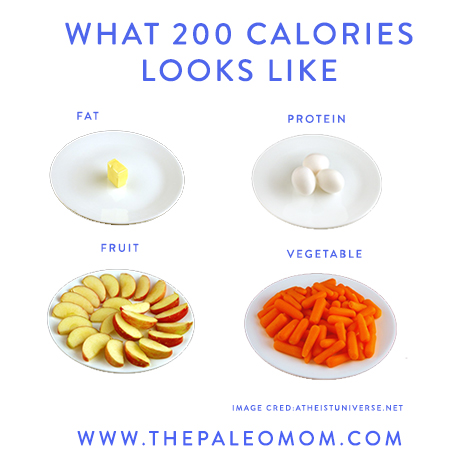

One of the most obvious reasons to eat our vegetables is that they are relatively less calorically dense than other Paleo foods; this means that we get more micronutrients and fewer calories from each bite. For example, 200 calories of a pure fat like ghee is just short of two tablespoons, whereas 200 calories of kale is over 6 cups (basically, I dare you to try to eat that much kale! LOL!).

When we eat lots of veggies, it gives us the opportunity to truly maximize our micronutrient intake (that is the vitamins, minerals, and other non-caloric nutritive molecules that our bodies use to function and stay healthy). Given that cravings can be a physical manifestation of micronutrient deficiencies, eating vegetables is one of the best ways to combat and prevent cravings during periods of weight loss. I’ve already summarized specific micronutrients to support weight loss in 10 Nutrients That Can Help You Burn Fat. Weight loss is actually quite demanding metabolically – we can easily become depleted in nutrients required for fatty acid metabolism, such as the B vitamins and vitamin A.

Importantly, plant matter is more likely to contain precursors of some vitamins rather than the active and/or bioavailable forms. For this reason, I recommend a diet that also includes well-sourced animal protein, including organ meats and skeletal muscle meat. This is the only way to meet our needs for fat-soluble vitamins apart from supplementation (which has its own limitations and does not replace our need for animal sources).

Fiber.

I have written extensively about the importance of fiber in The Fiber Manifesto. But, I still think fiber needs a shout-out for its potential role as a weight loss essential.

I have written extensively about the importance of fiber in The Fiber Manifesto. But, I still think fiber needs a shout-out for its potential role as a weight loss essential.

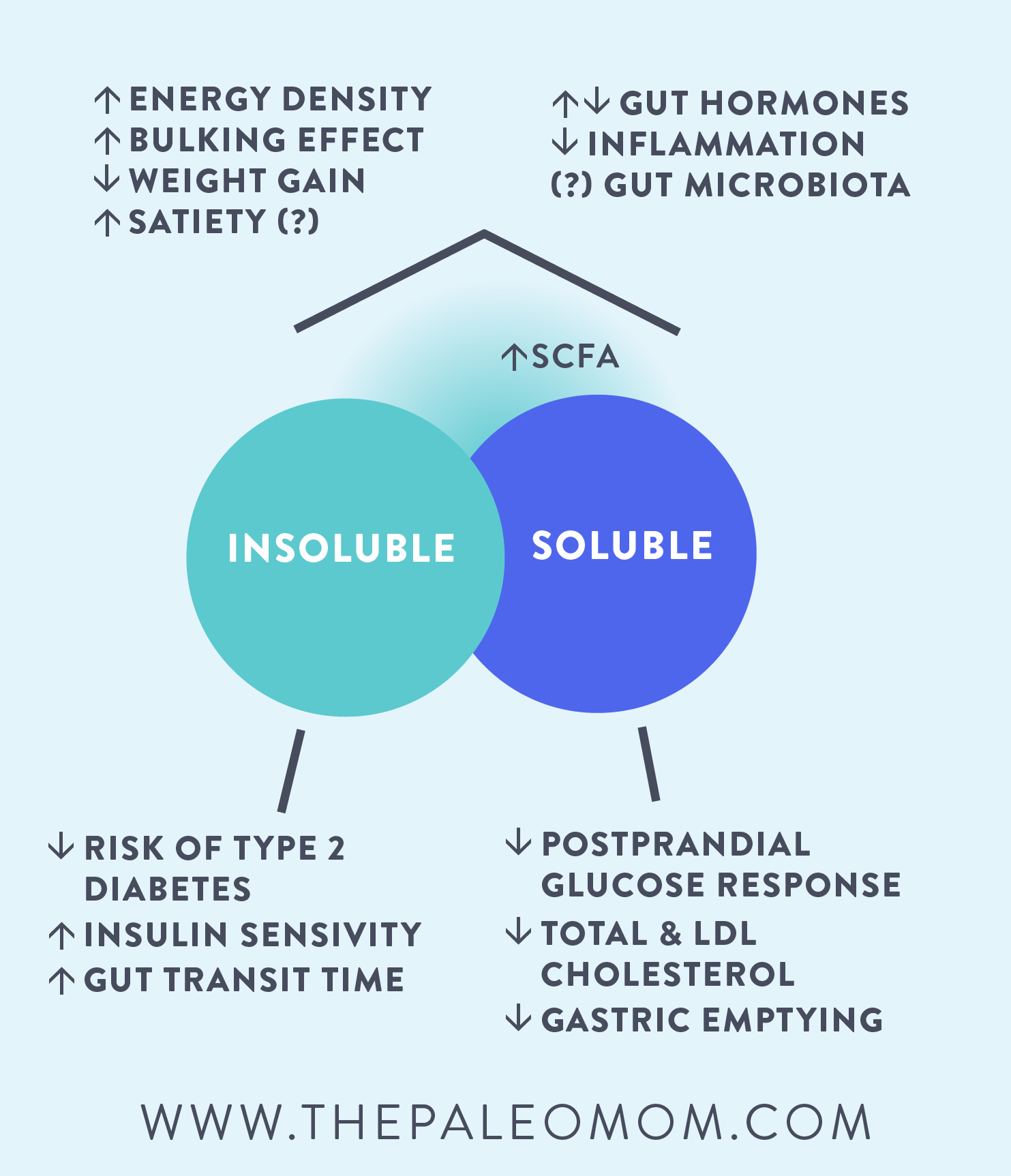

Though fiber isn’t an essential nutrient according to the FDA, I believe we all should be eating more of it. There are some very obvious and amazing ways that fiber (both insoluble and soluble – I talk about the different types in The Fiber Manifesto, Part 2) affect our health. Firstly, high fiber intake increases satiety, meaning that we feel more satisfied with our food more quickly. This significantly reduces our chance of overeating. Plus, fiber is essential for a healthy gut microbiome, which we know is critical for optimal health (including weight loss and weight maintenance). Indeed, the gut microbiome has been found to be different when we compare those of normal weight people with overweight/obesity. Fiber (or lack thereof) might be just one reason why the microbiomes are different. Finally, we know that fiber intake results in the creation of short chain fatty acids in the gut when fiber is fermented in the gut by the bacteria of the microbiome. Why does this matter? Short chain fatty acids are associated with many health markers, including better blood lipids, higher metabolism, and proper hormonal regulation.

For these reasons, I recommend that people trying to lose weight aim to eat at least 30 grams of fiber per day (though in general, the more, the better! Hunter-gatherers consume between 48 and 200 grams daily!). This is going to be most easily accomplished by eating a variety of vegetables, including leafy plant matter, cruciferous veggies (like broccoli and cabbage), and some roots and tubers. Start by determining how much fiber you’re currently eating and then slowly increase your intake until there’s 30 grams or more spread out between meals per day (and, bonus tip! Fiber helps with sleep too – an important lifestyle factor that we will discuss later). Increasing your fiber intake too quickly can lead to frequent and uncomfortable trips to the bathroom, so proceed with caution! Think of adding half a serving of veggies per day, or go even more slowly if you’re experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms.

Phytonutrients.

Phytochemicals are compounds in plants that, while not technically considered essential (meaning you must consume them to stay alive), are absolutely vital for optimal health and disease prevention. Phytochemicals are responsible for giving many fruits and vegetables their rich colors and unique scents, like the deep red of tomatoes or the aroma of garlic. They’re also a big reason why unprocessed plant foods (fruits and veggies in whole food form) are found to be disease-protective in study after study. Certain phytochemicals have the ability to slow the growth of cancer cells, help regulate hormones, prevent DNA damage, protect against oxidative stress, reduce inflammation, and induce apoptosis (death) in damaged cells (like a spring clean-up)—just to name a few of their beneficial activities. See The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important! and Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?.

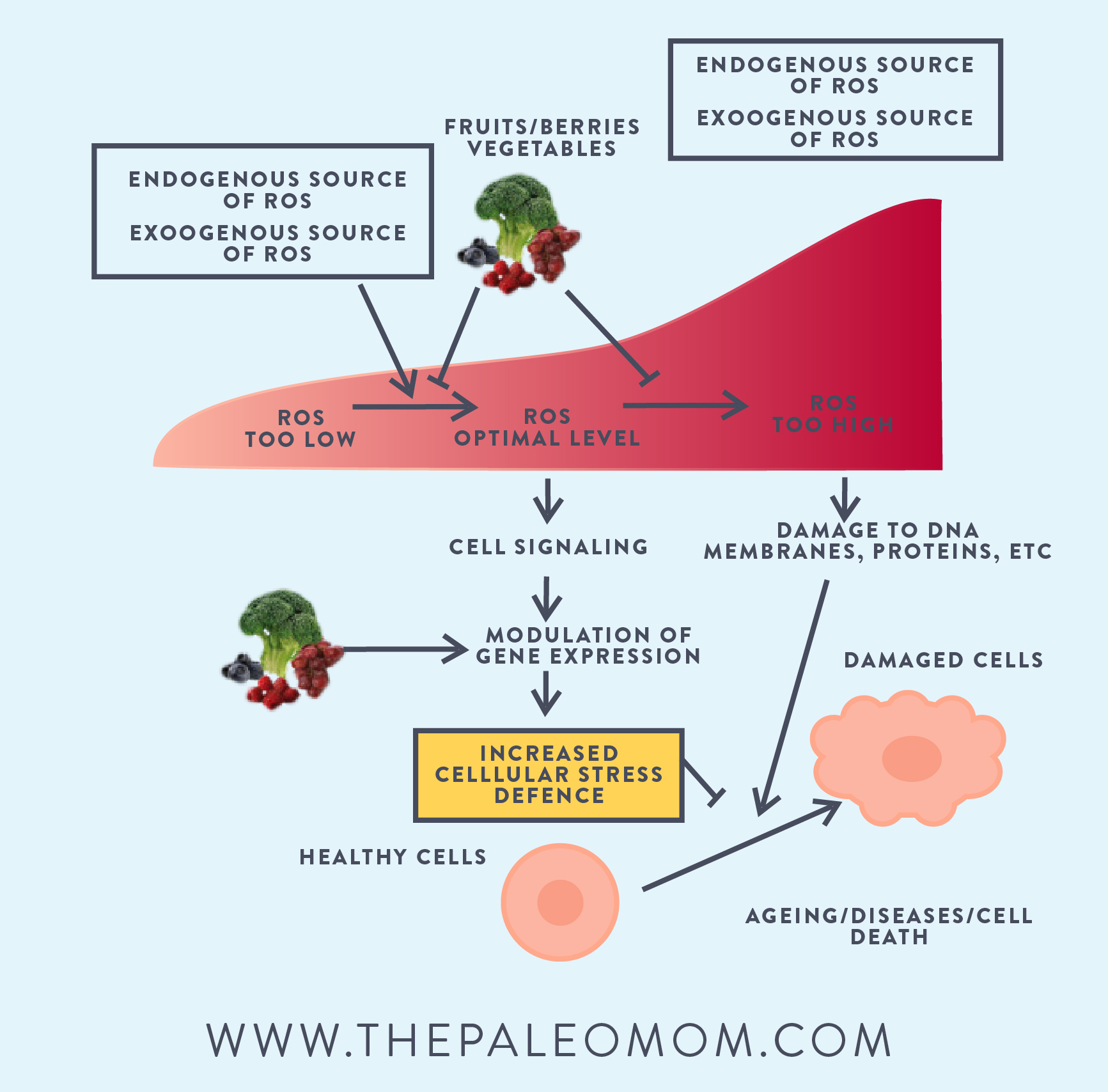

Phytonutrients are important for overall health, but they are absolutely essential while someone focuses on their weight loss. The reason is really simple and something I mentioned above: weight loss (aka fatty acid metabolism) is actually pretty hard on our bodies. The process of liberating fat from adipocytes (fat storage cells) and then converting the stored fat into glucose (the molecule that cells ultimately use for cellular respiration, to convert into cellular energy) creates free radicals. Our bodies actually want a certain number of free radicals that are used as reactive oxygen species (ROS). The ROS act in some other metabolic pathways as electron acceptors or receivers (with CoQ10 or one of the B vitamins), are utilized by antioxidants (like vitamins C or E), or act in the immune system as a defense mechanism. However, if we are losing weight and metabolizing a relatively large amount of stored fat, we can create too many ROSs, creating an imbalance that may lead to cellular damage. This is actually one of the arguments against losing weight too quickly – it can increase our chances of some diseases like cardiovascular disease and may speed up cellular aging. However, when we eat phytonutrients, we are helping to balance the equation.

How many servings a day do we need? Science hasn’t established an RDA for phytochemicals, but studies show that 5 servings a day is the cusp for seeing decreased risk of disease and 8 or more servings a day confers the lowest risks, and the more the merrier (are you seeing a trend here?).

The take-home message from all this science is that we must eat many servings of vegetables each day and with each meal. From a fiber, vitamin, mineral, and phytochemical perspective, 8-10 servings a day of a variety of vegetables is a really good target. And, variety is definitely a key word there! To ensure you’re tapping into the phytochemical wealth of plant foods (not to mention fiber and other micronutrients), load up on a wide spectrum spanning the whole rainbow: deep blue and purple berries and vegetables; bright red and orange citrus, tomatoes, and peppers; vibrant green leafy vegetables and crucifers (broccoli, Brussels sprouts, etc.); garlic and onions and leeks—the list goes on and on. Because different plant foods contain different types of phytochemicals, your best bet is to aim for diversity as well as quantity.

Macronutrient Manipulation: Worth It or All Hype?

We can’t talk about weight loss without reviewing some thoughts on the different macronutrients and how they contribute to the calories in-calories out equation as well as overall health. As we discuss the different macronutrients, never forget that all three contribute to cellular metabolism, and the process is pretty complicated. Assuming that we have excess fat, our bodies will utilize that fat for energy as long as we are within a caloric deficit and have the micronutrient sufficiency to utilize the necessary biochemical pathways.

Many people have purported that there are benefits to manipulating macronutrients (including low fat, low carb, and even ketogenic diets), claiming that this will bolster weight loss efforts. But, this effort isn’t supported by scientific research – in fact, studies attempting to confirm the weight loss improvements have actually debunked the concept altogether. Indeed, when calorie intake is held constant, different macronutrient ratios (such as low carb/high fat or high carb/low fat) don’t have a significantly different effect on the amount of body fat we lose (or on our overall energy needs). There’s no substantial evidence that specific macronutrient ratios have a “metabolic advantage” when it comes to burning more fat or changing our energy needs; the only thing that ends up influencing body mass is the calorie content of our diet. For example, a metabolic ward study from 1992 (where subjects were fed tightly controlled diets with equal calorie contents) found no detectable difference in the amount of energy people burned when eating extremely high fat, low carb diets (70% fat and 15% carbohydrate) versus extremely low fat, high carb diets (0% fat and 85% carbohydrate). And, another metabolic ward study found that when hypercaloric diets (meaning eating more calories that what is burned) with different macronutrient compositions were compared, calories alone accounted for people’s body fat gain. (See also New Scientific Study: Calories Matter).

Many people have purported that there are benefits to manipulating macronutrients (including low fat, low carb, and even ketogenic diets), claiming that this will bolster weight loss efforts. But, this effort isn’t supported by scientific research – in fact, studies attempting to confirm the weight loss improvements have actually debunked the concept altogether. Indeed, when calorie intake is held constant, different macronutrient ratios (such as low carb/high fat or high carb/low fat) don’t have a significantly different effect on the amount of body fat we lose (or on our overall energy needs). There’s no substantial evidence that specific macronutrient ratios have a “metabolic advantage” when it comes to burning more fat or changing our energy needs; the only thing that ends up influencing body mass is the calorie content of our diet. For example, a metabolic ward study from 1992 (where subjects were fed tightly controlled diets with equal calorie contents) found no detectable difference in the amount of energy people burned when eating extremely high fat, low carb diets (70% fat and 15% carbohydrate) versus extremely low fat, high carb diets (0% fat and 85% carbohydrate). And, another metabolic ward study found that when hypercaloric diets (meaning eating more calories that what is burned) with different macronutrient compositions were compared, calories alone accounted for people’s body fat gain. (See also New Scientific Study: Calories Matter).

That being said, some studies have found an advantage to eating higher levels of protein when it comes to preserving lean mass (muscle) or burning a higher proportion of body fat relative to other tissue. But, those findings aren’t consistent across all studies, and in some cases are gender-specific (with women having a greater advantage when it comes to lean mass preservation from high-protein diets). We can conclude that it’s best to have a complete protein with each meal and snack, which increases satiety and helps meet our daily protein needs (see also Plant-Based Protein: What is its Role in the Paleo Diet?). All in all, my general recommendation when it comes to macronutrients is that balance is key, within our individual needs and preferences, and the overarching goal should be to achieve a caloric deficit. Despite the simplicity of this recommendation, I still believe the other two macronutrients (carbs and fats), need more careful attention.

Carbohydrates Confusion: Proceed Intelligently, Not Cautiously!

Many people come to Paleo thinking that this is a low-carb lifestyle. However, that’s not the case (see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised). Considering the way that carbohydrates are both demonized and glorified for weight loss, I’m going to go ahead and take an unpopular stance here: they’re neither. While we’re talking about carb confusion, let’s spend some time dissecting the history of this issue and detail the downfalls of both extremes (high AND low).

Many people come to Paleo thinking that this is a low-carb lifestyle. However, that’s not the case (see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised). Considering the way that carbohydrates are both demonized and glorified for weight loss, I’m going to go ahead and take an unpopular stance here: they’re neither. While we’re talking about carb confusion, let’s spend some time dissecting the history of this issue and detail the downfalls of both extremes (high AND low).

The media and people outside of the community have been claiming that Paleo is a low-carb or zero-carb diet essentially since the movement began. Yes, eliminating processed carbohydrates is an essential part of the lifestyle, but there are a vast number of sources of carbohydrate in the Paleo template! In fact, if we want to think about it from the evolutionary biology perspective, there is some evidence that being able to harness more carbohydrates was one of the great contributors to the development of the human prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain that controls executive function, essentially what determines our thoughts and actions. It’s kind of a big deal.). See The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers.

However, there are known setbacks to eating too many carbohydrates while trying to lose weight. Monitoring our blood sugar regulation is absolutely essential here – knowing our fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin, and HbA1C (a 3-month measure of how much glucose is stored in our red blood cells). Even with pristine blood work, eating too many carbohydrates can undermine weight loss attempts. Here are the main reasons why I would hesitate before adopting a high-carb approach:

- Excess carbohydrates become stored fat. When we do not maintain a caloric deficit, the macronutrient that is stored as fat is actually carbohydrate, not fat. From a biochemical perspective, carbohydrates are easily converted to fats (triglycerides, specifically), so excess dietary carbs are converted and stored as fat in our cells. Eating too many carbs is like asking your body to store more energy for later – and it is happy to comply!

- Systemic inflammation. Consuming too many carbohydrates, notably sugars, is one of the triggers for elevated systemic inflammation. Sugar has been shown to increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines, an immune system messenger that ramps up inflammation.

Conversely, low carb is often touted as a tool for weight loss, because it theoretically keeps insulin levels low, allowing for more stored fat to be released as fuel for the body (the insulin hypothesis of weight loss). But, there is little to no scientific evidence supporting this theory, with the most recent data indicating that low-carb diets are actually simply a sneaky way to reduce calorie intake without actually counting them (yes, that means portion control! See New Scientific Study: Calories Matter). There are several reasons to avoid going too low carb:

- Hypothyroidism. You may have heard the recommendation that we all need to eat enough carbs to support our thyroid gland and hormone production. It’s true – you can induce hypothyroidism (in which someone doesn’t have enough thyroid hormone). Eating enough carbohydrate, specifically having enough available glucose, is essential for the production of functional thyroid hormone. This is the reason that adding carbohydrate into a chronically low-carb diet might actually jumpstart weight loss: the additional thyroid hormone stimulates metabolism!

- Mood problems. Serotonin, the “happy neurotransmitter,” is actually produced largely in the gut. And, you guessed it – this process depends on the presence of glucose! (That stereotypical low carb crankiness is due in part to this phenomenon) If you have a propensity towards depression or anxiety, cutting off your own serotonin supply might not be the best idea! Science also says that long-term low carb might be problematic for cognitive function, so things like work performance might be sacrificed on a low carb diet (I know I’ve experienced this personally!).

- Insulin & hunger dysregulation. Contrary to the popular belief, there are some people who actually experience insulin dysregulation once they go too low carb. A recent study on the participants of the popular show The Biggest Loser demonstrated that there are long-term metabolic consequences that affect hunger as well as one’s ability to lose weight.

- Gut health. The carbohydrates in our diets feed, in part, our microbiome. When we don’t eat enough, we lose diversity in our microbiome. As we already discussed, this can have huge consequences for our health, including not just digestive upset but also issues with hormone regulation (like appetite, weight management, and hormone balance).

- Sleep. Because of the great role that carbohydrates play in our hormone balance, they are essential for healthy sleep. In fact, research has specifically demonstrated that less sugar and more fiber is the best formula for deep sleep (in combination with so many other factors! This topic is discussed in greater detail in my epic online sleep program, Go to Bed, and see The Link Between Sleep and Your Weight).

This is not to mention the importance of getting enough carbohydrates in certain states of being, like if you’re an athlete (our bodies NEED those carbs to make glycogen and maximize our athletic performance! The biochemical pathways are clear on this issue) or a pregnant woman (your growing fetus needs those carbohydrates for essential brain growth and other aspects of development). The notion that we need carbohydrates during pregnancy was corroborated by a recent journal article that demonstrated a higher-carb diet being better for the metabolism of women (compared to a low carb high fat diet).

When it comes to weight loss, we need to eat enough carbohydrate to maintain health and support our metabolism (that means supporting the thyroid, too!). Planning to stay between 100 and 200 grams of carbohydrate per day is a good “middle of the road” plan. See How many carbs should you eat?

Paleo Fats: Moderation Still Matters

Fat is a notorious entity in the health and fitness industry. But, the historical recommendations to avoid fat at all costs are wildly misguided. Not only is dietary fat not bad for you, it’s critical for your health. You need to eat fat in order to absorb vitamins A, D, E, and K (which between them affect every system in your body). Fat is essential for cell construction, nerve function, digestion, and for the formation of the hormones that regulate everything from metabolism to circulation. The membranes of every cell in your body are composed of fat molecules. Your brain is composed of more than 60% fat and cholesterol. But, that doesn’t mean we should eat all fats with abandon – especially considering fatty acids (the molecules that compose fats) contain more calories per gram (9 kcal) compared to either protein and carbohydrate (4 kcal per gram). Let’s review some of the key fatty acid players to keep in mind as we focus on the details of our nutritional approach to weight loss.

Fat is a notorious entity in the health and fitness industry. But, the historical recommendations to avoid fat at all costs are wildly misguided. Not only is dietary fat not bad for you, it’s critical for your health. You need to eat fat in order to absorb vitamins A, D, E, and K (which between them affect every system in your body). Fat is essential for cell construction, nerve function, digestion, and for the formation of the hormones that regulate everything from metabolism to circulation. The membranes of every cell in your body are composed of fat molecules. Your brain is composed of more than 60% fat and cholesterol. But, that doesn’t mean we should eat all fats with abandon – especially considering fatty acids (the molecules that compose fats) contain more calories per gram (9 kcal) compared to either protein and carbohydrate (4 kcal per gram). Let’s review some of the key fatty acid players to keep in mind as we focus on the details of our nutritional approach to weight loss.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids.

You’ve probably heard the most about omega-3 fatty acids compared to the other types of fats we’ll discuss in this post. That’s because dietary deficiency in omega-3s has been linked to dyslexia, violence, depression, anxiety, memory problems, Alzheimer’s disease, weight gain, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, eczema, allergies, asthma, inflammatory diseases, arthritis, diabetes, auto-immune diseases and many others. But not all omega-3 fatty acids are created equal. There are three forms. ALA is found in flax seeds, pumpkin seeds, and many other plant sources of polyunsaturated fats. Your body mainly needs the other two forms (the difference is actually the length of the molecule, ALA is the shortest and DHA is the longest), DHA and EPA, which are found in fish, pasture-raised (and omega-3 enriched) eggs, free-range poultry, pasture-raised/grass-fed meat, dairy from pasture-fed animals, and wild game. ALA needs to be converted to DHA and EPA, so the bioavailability of ALA is much less than the other omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-6 Fatty Acids.

These are also polyunsaturated fats. Many diet gurus are now labeling linoleic acid (the dominant form of omega-6 found in grains, modern vegetable oils and meat from grain-fed animals) as the True Bad Fat. But, there are no bad fats in nature. The problem is the quantity of omega-6 fats that has insinuated itself into the modern human diet. Ancestral diets consisted of a 1:1 to 1:2 ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids (in some areas, it may have been as high as 1:4). When grain was introduced into the human diet (and to the diets of grazing animals that we raise for food) approximately 10,000 years ago, we started increased the proportion of our dietary fat that is omega-6s. And this has increased even more over the last 100 years, increasing exponentially with the introduction of canola oil into our diets in the mid 1980s). Modern Western diets contain anywhere from a 1:10 to a 1:40 ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids. This is NOT what nature intended for our optimal health.

There is a complex interplay between omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in your body, and both are essential for life. Generally, omega-3 fatty acids contribute to anti-inflammatory processes, whereas omega-6 fatty acids are pro-inflammatory. “Pro-inflammatory” sounds bad, but, in the balanced quantities that our ancestors consumed, it is critical for wound healing and fighting infections. But, when you combine excessive omega-6 fatty acid consumption with the irritation to the gut lining caused by gluten and other lectins and excessive carbohydrate consumption (which is also pro-inflammatory), our bodies have constant low-level inflammation. This sets the stage for many diseases, decreased ability to fight infection, and exaggerated allergies. Thus, focusing on eating a balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids is one of the best ways to support our bodies as we lose weight.

Saturated Fatty Acids.

We are huge fans of saturated fat in this community, and with reason! The love of saturated fat is in large part a response to the fat-phobic culture that most of us were raised in. And it’s true – we need saturated fat to live. However, I must caution against excess consumption of saturated fats, especially for people trying to lose weight.

We are huge fans of saturated fat in this community, and with reason! The love of saturated fat is in large part a response to the fat-phobic culture that most of us were raised in. And it’s true – we need saturated fat to live. However, I must caution against excess consumption of saturated fats, especially for people trying to lose weight.

Like sugar, saturated fat has been demonstrated to increase the release of cytokines, which can lead to systemic inflammation (something we are desperately trying to reduce and avoid as we prepare our bodies for weight loss!). There are other reasons to stay cautious when it comes to saturated fats: it can impact our LDL (the “bad cholesterol”), lead to impaired endothelial cell function, damage our gut microbiome, and reduce the quality of our sleep! Yikes. See Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere in Between?

So, how do we interpret this information? Overall, the research points towards a moderate fat intake (30-40% of calories, perhaps as high as 50% for some people) and moderate saturated fat intake (10-20% of calories) being ideal for maintaining all aspects of our health. See Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers. I believe this ratio stays true for people trying to lose weight as well, which means we pay special attention to the amount of cooking oils and other fats we are using (I know I’ve personally found that accidentally adding too much fat can undermine my goals).

Putting It All Together

Anyone who has attempted a significant weight loss (or any, for that matter) knows that this can be a monumental task that requires a lot of effort and commitment (notice, I didn’t say willpower). As someone who has maintained over a 100-pound weight loss for five years, I know how daunting the prospect can be. But, healthy and sustainable weight loss is absolutely achievable!

Here’s what you need to know:

- A caloric deficit is essential. That means you eat fewer calories than you burn. Increasing activity is clearly helpful here, but the biggest factor is how many calories you take in.

- Slow and steady wins the race. Thanks to leptin’s duel response to overeating and undereating (see The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin), aiming for a modest (say 10 to 20%) caloric deficit typically leads to more easily-maintainable weight loss. That’s a typical spontaneous caloric deficit achieved simply by following a standard Paleo diet.

- Note that nutrient deficiencies can cause increased appetite and cravings, as well as inhibit our body’s ability to access and burn stored fat. Thus, nutrient-density is key. (See 3 Ways to Up Your Nutrient Game and 10 Nutrients that Can Help You Burn Fat)

- The best strategy to spontaneously achieve a caloric deficit is to eat tons of veggies. Aim for 8-10 servings and at least 30g of fiber from veggies and some fruit daily.

- Low carb and low fat won’t help you lose weight. Instead, aim for balanced macronutrients (say 30-30-40 and it doesn’t really matter which one is 40%) and make sure to get enough protein to support muscle mass and metabolism.

- Eating a protein-packed breakfast sets you up for better food choices during the day. (See Is Breakfast Really the Most Important Meal of The Day?)

- Avoid highly palatable foods (yes, there are some in within the Paleo framework) like natural sugars (like honey), Paleo treats, and nut-based baked goods.

- Getting enough sleep and managing stress help regulate appetite and reduce cravings (see Go To Bed).

- Get back to Paleo basics. Generally, your plate will contain a 5-8oz serving of not-too-fatty not-too-lean meat or seafood and 3 or more servings of veggies. Think of nuts and seeds as condiments. Limit fruit to 3-5 servings per day (see Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?)

- When in doubt, count calories. No, this isn’t a great long-term solution. Instead, use it as a tool to educate yourself on what your plates should look like and use this information to improve your food choices.

I just hinted at a few lifestyle inputs. Yes, we all know that eating right isn’t the only factor that goes into weight loss; so, stay on the lookout for Part 2 of this series, in which I’ll discuss the Paleo-centric lifestyle modifications necessary to support our weight loss efforts.

Citations

Bray GA, et al. “Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial.” JAMA. 2012 Jan 4;307(1):47-55.

Dahl WJ, Agro NC, Eliasson ÅM, et al. Health Benefits of Fiber Fermentation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;:1-10.

Farnsworth E, et al. “Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jul;78(1):31-9.

Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016.

Francesca De Filippis, Nicoletta Pellegrini, Lucia Vannini, Ian B Jeffery, Antonietta La Storia, Luca Laghi, Diana I Serrazanetti, Raffaella Di Cagno, Ilario Ferrocino, Camilla Lazzi, Silvia Turroni, Luca Cocolin, Patrizia Brigidi, Erasmo Neviani, Marco Gobbetti, Paul W O’Toole, Danilo Ercolini. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut, 2015; gutjnl-2015-309957 DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309957

Hernandez TL, Van pelt RE, Anderson MA, et al. Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Randomized to a Higher-Complex Carbohydrate/Low-Fat Diet Manifest Lower Adipose Tissue Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, Glucose, and Free Fatty Acids: A Pilot Study. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):39-42.

Hirsch J, et al. “Diet composition and energy balance in humans.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Mar;67(3 Suppl):551S-555S.

Hoch T, et al. “Snack food intake in ad libitum fed rats is triggered by the combination of fat and carbohydrates.” Front Psychol. 2014 Mar 31;5:250.

Jonasson L, Guldbrand H, Lundberg AK, Nystrom FH. Advice to follow a low-carbohydrate diet has a favourable impact on low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes compared with advice to follow a low-fat diet. Ann Med. 2014;46(3):182-7.

Jönsson T, et al. “Subjective satiety and other experiences of a Paleolithic diet compared to a diabetes diet in patients with type 2 diabetes.” Nutr J. 2013 Jul 29;12:105. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-105.

Kaplan HS, Hill KR, Lancaster JB, Hurtado AM. A Theory of Human Life History Evolution: Diet, Intelligence, and Longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology 9:156-185, 2000.

Leibel RL, et al. “Energy intake required to maintain body weight is not affected by wide variation in diet composition.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Feb;55(2):350-5.

Luscombe-Marsh ND, et al. “Carbohydrate-restricted diets high in either monounsaturated fat or protein are equally effective at promoting fat loss and improving blood lipids.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Apr;81(4):762-72.

Manheimer EW, et al. “Paleolithic nutrition for metabolic syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Oct;102(4):922-32. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.113613. Epub 2015 Aug 12. Review.

Miller B, O’connor H, Orr R, Ruell P, Cheng HL, Chow CM. Combined caffeine and carbohydrate ingestion: effects on nocturnal sleep and exercise performance in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(12):2529-37.

Nehme P, Marqueze EC, Ulhôa M, Moulatlet E, Codarin MA, Moreno CR. Effects of a carbohydrate-enriched night meal on sleepiness and sleep duration in night workers: a double-blind intervention. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31(4):453-60.

Oliveira MC, Menezes-garcia Z, Henriques MC, et al. Acute and sustained inflammation and metabolic dysfunction induced by high refined carbohydrate-containing diet in mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(9):E396-406.

Otten J, et al. “Benefits of a Paleolithic diet with and without supervised exercise on fat mass, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016 May 27. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2828. [Epub ahead of print]

Poppitt SD & Prentice AM. “Energy density and its role in the control of food intake: evidence from metabolic and community studies.” Appetite. 1996 Apr;26(2):153-74.

Rajaie S, Azadbakht L, Saneei P, Khazaei M, Esmaillzadeh A. Comparative effects of carbohydrate versus fat restriction on serum levels of adipocytokines, markers of inflammation, and endothelial function among women with the metabolic syndrome: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63(1-2):159-67.

Ramirez I & Friedman MI. “Dietary hyperphagia in rats: role of fat, carbohydrate, and energy content.” Physiol Behav. 1990 Jun;47(6):1157-63.

Raychaudhuri N, Thamotharan S, Srinivasan M, Mahmood S, Patel MS, Devaskar SU. Postnatal exposure to a high-carbohydrate diet interferes epigenetically with thyroid hormone receptor induction of the adult male rat skeletal muscle glucose transporter isoform 4 expression. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25(10):1066-76.

Santos I, Vieira PN, Silva MN, Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ. Weight control behaviors of highly successful weight loss maintainers: the Portuguese Weight Control Registry. J Behav Med. 2016.

Sho H. History and characteristics of Okinawan longevity food. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001;10(2):159-64.

Sofer S, Eliraz A, Madar Z, Froy O. Concentrating carbohydrates before sleep improves feeding regulation and metabolic and inflammatory parameters in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;414:29-41.

Sofer S, Eliraz A, Madar Z, Froy O. Concentrating carbohydrates before sleep improves feeding regulation and metabolic and inflammatory parameters in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;414:29-41.

Swinburn B, et al. “Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Dec;90(6):1453-6.

Turner-McGrievy GM, et al. “Comparative effectiveness of plant-based diets for weight loss: a randomized controlled trial of five different diets.” Nutrition. 2015 Feb;31(2):350-8.

Wyckoff EP, Evans BC, Manasse SM, Butryn ML, Forman EM. Executive functioning and dietary intake: Neurocognitive correlates of fruit, vegetable, and saturated fat intake in adults with obesity. Appetite. 2016;111:79-85.