When it comes to losing weight, there’s dozens of effective diets to choose from. It’s true that just about every approach geared at weight loss works. But what’s not true is that every way we can lose weight is healthy, plus it’s often very tough to maintain that weight loss. That’s where focusing on healthy weight loss comes in. Healthy weight loss means we are successfully losing weight, mostly fat including visceral fat, while also reducing inflammation, promoting a healthy metabolism, and regulating hormones and neurotransmitters. When we take care to lose weight in this way, our chances of keeping it off are much higher. Unfortunately, there’s a plethora of myths out there about weight loss, even within the Paleo community, and these can steer people down weight loss paths that aren’t doing them any favors over the long haul. And, that’s why I’ve chosen to delve into this topic in such detail in this new series of blog posts (for Parts 1 and 3 of this series, see(for parts 2 and 3 of this series, see Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 1: Modifying Dietary Choices to Support Fat Metabolism and Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 3: Troubleshooting Weight Loss Difficulties).

In Part 1 of this series, Modifying Dietary Choices to Support Fat Metabolism, I detailed many of the nutritional strategies we can employ to promote weight loss within a Paleo framework. But, we all know that Paleo isn’t just a diet – it’s a lifestyle and one that promotes our healthiest selves by looking at human health through an evolutionary biological lens. Likewise, we know that weight loss isn’t an isolated effort, physiologically-speaking, and the “calories in, calories out” model of weight loss is better in theory than in practice.

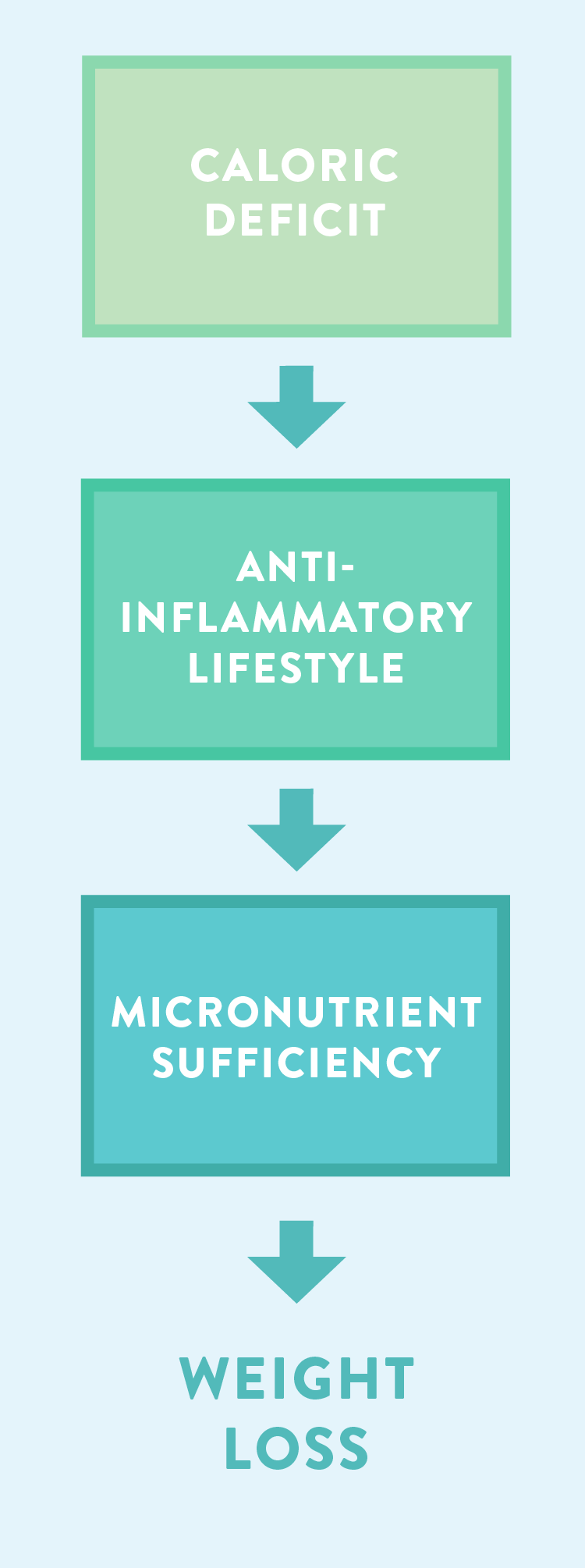

It’s true: for most people, healthy weight loss requires more than just nutritional changes. Changes to lifestyle are equally (if not more!) important. But in fact, the three goals to promote healthy weight loss that we established in our first post still apply here! Let’s review them now:

It’s true: for most people, healthy weight loss requires more than just nutritional changes. Changes to lifestyle are equally (if not more!) important. But in fact, the three goals to promote healthy weight loss that we established in our first post still apply here! Let’s review them now:

- Establish a caloric deficit

- Reduce/eliminate systemic inflammation

- Support biochemical pathways of fat and glucose metabolism

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

For the lifestyle piece of this puzzle, let’s continue to think about our weight loss in terms of these goals. These factors are equally as important as we consider how to tweak our lifestyle to support weight loss; however, you’ll see that reducing systemic inflammation is the biggest player when it comes to lifestyle management. Systemic inflammation, known as low-grade immune system activation throughout the body (rather than targeted immune activation against a microbe), has been consistently associated with increases in weight and with difficulty in weight loss and maintenance. Likewise, inflammation reduction has been implicated in aiding weight loss, and weight loss is associated with lower overall inflammation. We are going to talk about some of the details

Because weight loss is a very metabolically challenging thing, we want to provide our bodies with the tools to accomplish this task (i.e., the micronutrients) AND we want to make sure to send every signal to our bodies that we don’t need to store this fat anymore. Basically, the body wants to keep fat stored in case of emergency (like famine, etc. – things we don’t need to worry about in our modern world!), so we need to tell it (through our thoughts and behaviors) that we are safe and sound, we can use that stored energy as fuel now.

This task is trickier than one might think, so I’ve developed the 4 S’s of weight loss lifestyle: sleep, steps, stress management, and sustainability! Let’s go through each suggestion, including the reasoning behind this recommendation and how to implement it.

Sleep: The Key To Successful Weight Loss

My obsession with sleep is no secret (I did create an epic online program to help you improve yours, after all! See Go to Bed if you want to become a sleep overachiever like me). On top of all of the amazing benefits of getting enough sleep (quantity AND quality), there are specific reasons to ensure that sleep is a top priority while aiming for weight loss – namely, there is tons of scientific evidence suggesting that lack of sleep is a significant contributor to the obesity crisis. Yes, if you aren’t getting enough good sleep, all the other effort you’re making to lose weight becomes moot.

My obsession with sleep is no secret (I did create an epic online program to help you improve yours, after all! See Go to Bed if you want to become a sleep overachiever like me). On top of all of the amazing benefits of getting enough sleep (quantity AND quality), there are specific reasons to ensure that sleep is a top priority while aiming for weight loss – namely, there is tons of scientific evidence suggesting that lack of sleep is a significant contributor to the obesity crisis. Yes, if you aren’t getting enough good sleep, all the other effort you’re making to lose weight becomes moot.

Risk Factors

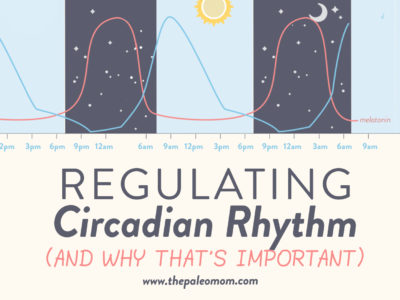

There is some striking evidence about how sleep deprivation contributes to risk for obesity, which is a foundation for the argument that getting enough sleep can aid in establishing a lower weight baseline. Sleep debt, the amount of sleep we’ve missed over time, dramatically impacts risk of obesity and insulin resistance (just one of the metabolic issues that can make it difficult to lose weight). Sleeping less than 6 hours per night increases risk of obesity by 55% in adults (90% in children!). But, when it comes to obesity, researchers have teased out some other fascinating links between how we sleep and obesity risk. Variability in bedtime during the week >2 hours increases risk of obesity by 14%. That means that if you normally go to bed at 10pm on weeknights and stay up until midnight Saturday for a party, your risk of obesity is higher. Sleep duration variability increases risk of obesity by 63% for each hour of standard deviation. That means that if some nights you get 6 hours and other nights you try to make up for it and sleep 9 hours, that inconsistency is dramatically increasing risk of obesity! It’s also important to sync our sleep time with the sun: following the night owl patterns of late-to-bed, late-to-rise doubles risk of obesity compared to early-to-bed, early-to-rise, even in people who get enough sleep!

Research has shown time and again that there is a direct relationship between sleep duration (how long you sleep at night) and weight problems over time. Short sleep duration is specifically implicated in the development of obesity, though getting both too little and too much sleep is related to weight gain.

There are many hypotheses seeking to explain these findings, but there are two main topics that are best described in the literature: hunger hormones and the dopamine-food addiction relationship (see also The Link Between Sleep and Your Weight).

Hormones

Medical research also shows that there’s a stronger connection between obesity and lack of sleep than any diet factor. One mechanism by which inadequate sleep increases your risk of weight gain and obesity is its profound effects on hunger hormones and metabolism.

Hormones are the way that different organ systems communicate with each other; one hormone may be released by a central organ, like the liver, and circulate the blood to act on receptors at the cell surface of the skin and then give more feedback to the brain! So, small changes in the amount of hormones in circulation can have a huge overall effect. Hormones are also hard to monitor, as they fluctuate by the hour, day, month, and season!

Sleep is absolutely critical for keeping our hormones in balance. Through changes in hormone signaling (both our sensitivity and the amounts that we produce) throughout the body, not getting enough sleep alters food preferences (towards more energy-dense, highly palatable foods), increases hunger, decreases fat metabolism, and increases the stress response, which affects basal metabolic rate.

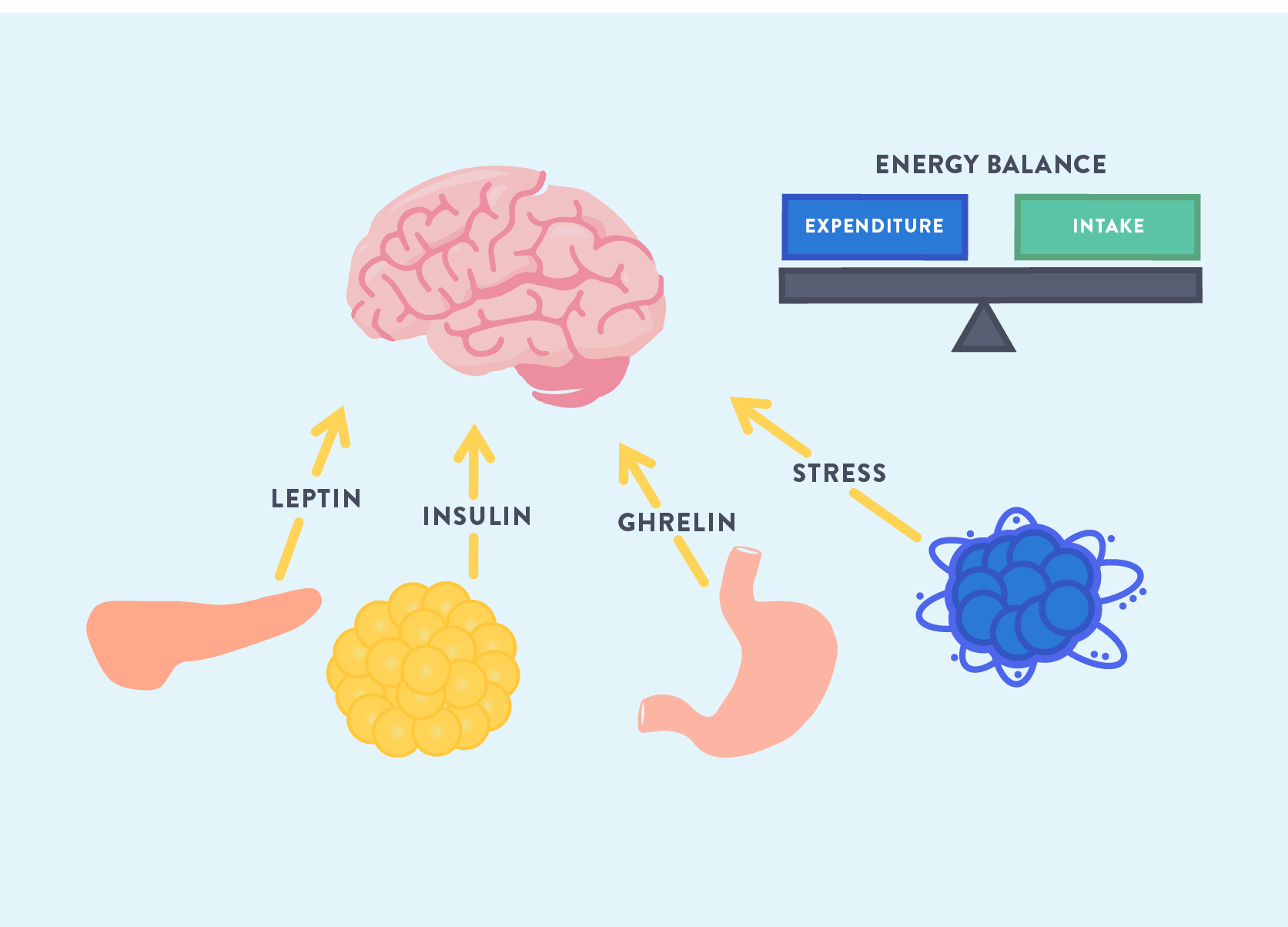

Inadequate sleep has profound effects on hunger hormones and metabolism (and a fun fact: hunger hormones such as insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol are also important modulators of the immune system, so this also links back to our discussion of inflammation! See The Hormones of Hunger and The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin). For example, when food intake is measured following sleep deprivation (5 consecutive days of 4 hours sleep), people tend to eat substantially (20%!) more than normal. However, it doesn’t take five full days of inadequate sleep to see dramatic effects on insulin, cortisol, and leptin. These hormones, plus ghrelin, are said to control hunger and satiety and should, in theory, all work together to balance your energy intake and expenditure (remember our discussions on caloric deficits in Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 1: Modifying Dietary Choices to Support Fat Metabolism and New Scientific Study: Calories Matter? This phenomenon is a key player!). Before we examine how inadequate sleep negatively affects these hormones, let’s explain what their roles are in the body.

Inadequate sleep has profound effects on hunger hormones and metabolism (and a fun fact: hunger hormones such as insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol are also important modulators of the immune system, so this also links back to our discussion of inflammation! See The Hormones of Hunger and The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin). For example, when food intake is measured following sleep deprivation (5 consecutive days of 4 hours sleep), people tend to eat substantially (20%!) more than normal. However, it doesn’t take five full days of inadequate sleep to see dramatic effects on insulin, cortisol, and leptin. These hormones, plus ghrelin, are said to control hunger and satiety and should, in theory, all work together to balance your energy intake and expenditure (remember our discussions on caloric deficits in Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo, Part 1: Modifying Dietary Choices to Support Fat Metabolism and New Scientific Study: Calories Matter? This phenomenon is a key player!). Before we examine how inadequate sleep negatively affects these hormones, let’s explain what their roles are in the body.

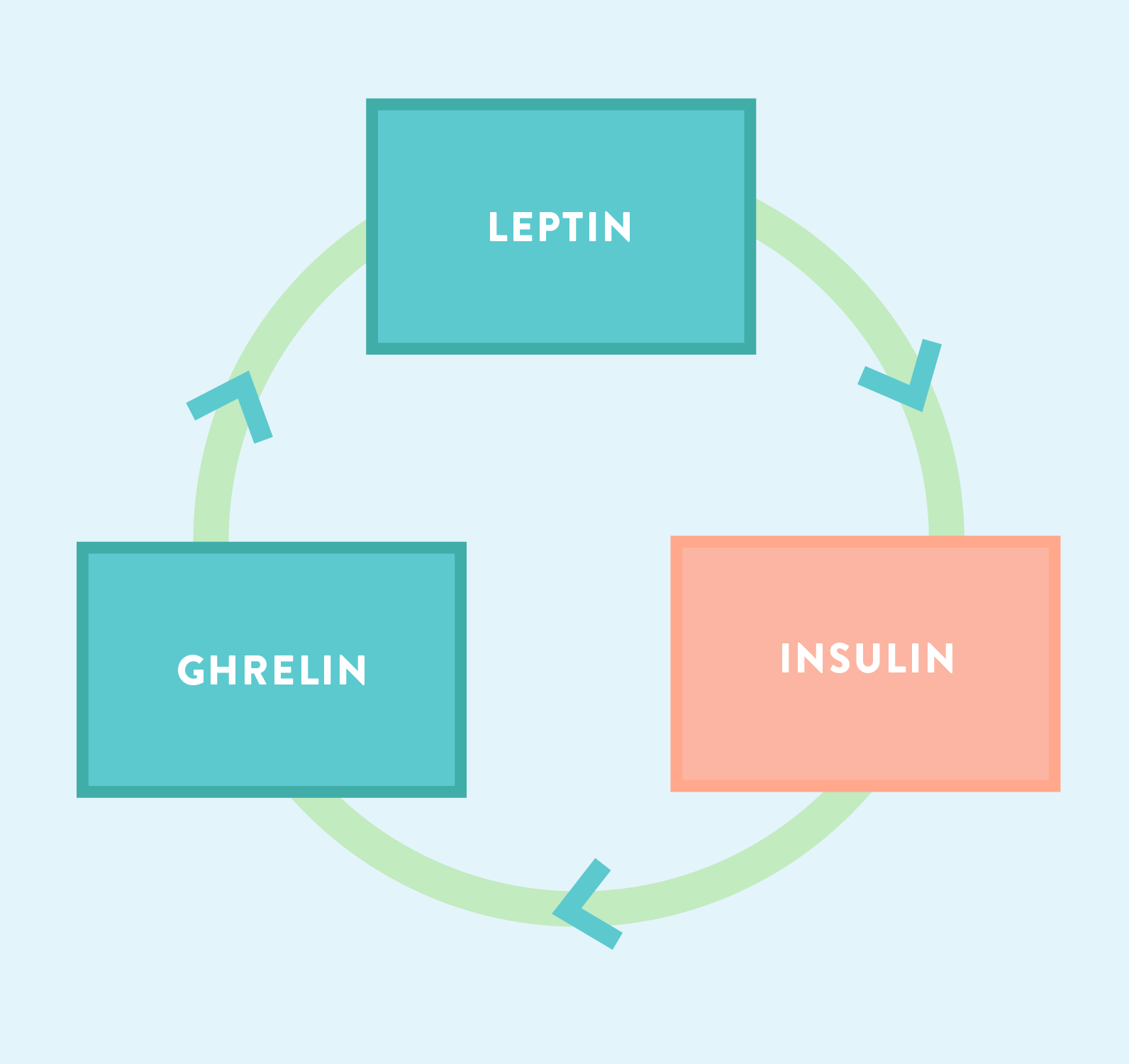

Insulin is released by the pancreas in response to elevated blood sugar, and it facilitates the transport of glucose into the cells of our bodies and signals for the liver to convert excess glucose to glycogen and triglycerides in the liver (the latter and then sent into circulation – we measure them in most routine blood lipid panels). Additionally, insulin is responsible for communicating with the brain about how much body fat/adipose tissue we have; that is, it tells the brain whether or not we should eat more or less, and it informs the brain about the energy status of our bodies (basically, whether we have too much or too little fat on our bodies). This second role is one of the main reasons that we must consider insulin regulation when it comes to healthy weight loss; when this hormone becomes dysregulated, we are more at risk for our brains being confused about how much body fat we actually have (either too much or too little!). We are going to talk more about the barrier of insulin resistance in Part 3 of the Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo series.

Insulin is released by the pancreas in response to elevated blood sugar, and it facilitates the transport of glucose into the cells of our bodies and signals for the liver to convert excess glucose to glycogen and triglycerides in the liver (the latter and then sent into circulation – we measure them in most routine blood lipid panels). Additionally, insulin is responsible for communicating with the brain about how much body fat/adipose tissue we have; that is, it tells the brain whether or not we should eat more or less, and it informs the brain about the energy status of our bodies (basically, whether we have too much or too little fat on our bodies). This second role is one of the main reasons that we must consider insulin regulation when it comes to healthy weight loss; when this hormone becomes dysregulated, we are more at risk for our brains being confused about how much body fat we actually have (either too much or too little!). We are going to talk more about the barrier of insulin resistance in Part 3 of the Healthy Weight Loss with Paleo series.

Leptin is another hormone related to the complicated way that our brains calculate how much we need to eat or move more (and these pathways regulate our behavior, whether we’re aware of it or not!). Fat storage cells, called adipocytes, produce the hormone leptin, which acts as a negative feedback control for adiposity (fatness). “Negative feedback” just means that increases in the amount of leptin lead to an inhibitory action somewhere else. Leptin is secreted by adipocytes in direct proportion to the amount of stored body fat, particularly with the amount of subcutaneous fat. When we have a good amount of fat stores (and yes, this is somewhat subjective and depends upon our own genetics and other factors! Weight maintenance and hormone homeostasis is complicated!), leptin is released and tells your brain that you have enough energy so you don’t need to eat anymore and “hey, let’s get moving!” These changes are very subtle relative to our cognitions. When we have high leptin levels, e aren’t just going to have the sudden thought that we need to head to the gym (though, wouldn’t that be wonderful?). Instead, these hormones work very delicately on our drive to exercise to either expend or conserve more energy slowly over time. As such, leptin is responsible for changes over a long period of time that accumulate to have a big impact on your body fat.

Leptin is another hormone related to the complicated way that our brains calculate how much we need to eat or move more (and these pathways regulate our behavior, whether we’re aware of it or not!). Fat storage cells, called adipocytes, produce the hormone leptin, which acts as a negative feedback control for adiposity (fatness). “Negative feedback” just means that increases in the amount of leptin lead to an inhibitory action somewhere else. Leptin is secreted by adipocytes in direct proportion to the amount of stored body fat, particularly with the amount of subcutaneous fat. When we have a good amount of fat stores (and yes, this is somewhat subjective and depends upon our own genetics and other factors! Weight maintenance and hormone homeostasis is complicated!), leptin is released and tells your brain that you have enough energy so you don’t need to eat anymore and “hey, let’s get moving!” These changes are very subtle relative to our cognitions. When we have high leptin levels, e aren’t just going to have the sudden thought that we need to head to the gym (though, wouldn’t that be wonderful?). Instead, these hormones work very delicately on our drive to exercise to either expend or conserve more energy slowly over time. As such, leptin is responsible for changes over a long period of time that accumulate to have a big impact on your body fat.

Ghrelin is the final satiety hormone, and it is kind of the “opposite” of the other two: it regulates our hunger sensations. Have you ever heard the statement “it takes 20 minutes for your stomach to even know that it’s full” before? That would be the layperson’s understanding of ghrelin–and, like almost all examples of colloquialisms, this generalization isn’t quite right. Unlike leptin and insulin, ghrelin is released by the gastrointestinal tract to tell our body that it’s hungry. The mechanism of release is based on the physical status of the stomach. When it’s empty, cells lining the stomach release ghrelin, which talks to the brain in the same way that the other satiety hormones do (in fact, ghrelin even uses the same receptors as leptin). Once the stomach is full of food, it stops releasing ghrelin, and we realize that we’re satiated. Optimizing ghrelin function (and even using it therapeutically, like an intravenous drug) is linked to improving both metabolism and inflammation! How cool is that? So, even though you may not hear about this hormone as much in the media, its importance is supercritical too.

Ghrelin is the final satiety hormone, and it is kind of the “opposite” of the other two: it regulates our hunger sensations. Have you ever heard the statement “it takes 20 minutes for your stomach to even know that it’s full” before? That would be the layperson’s understanding of ghrelin–and, like almost all examples of colloquialisms, this generalization isn’t quite right. Unlike leptin and insulin, ghrelin is released by the gastrointestinal tract to tell our body that it’s hungry. The mechanism of release is based on the physical status of the stomach. When it’s empty, cells lining the stomach release ghrelin, which talks to the brain in the same way that the other satiety hormones do (in fact, ghrelin even uses the same receptors as leptin). Once the stomach is full of food, it stops releasing ghrelin, and we realize that we’re satiated. Optimizing ghrelin function (and even using it therapeutically, like an intravenous drug) is linked to improving both metabolism and inflammation! How cool is that? So, even though you may not hear about this hormone as much in the media, its importance is supercritical too.

I know what you must be thinking: what do these hormones have to do with sleep?! Well, there is a huge body of literature suggesting that sleep quality and quantity is critical for the regulation of each of these hormones. And, while there are many mechanisms to suggest that sleep is critical for our overall health and weight loss, the one that I believe most directly contributes to weight problems is that lack of sleep directly impacts the satiety of hunger hormones. To put it simply, not getting enough sleep up-regulates ghrelin (making us more hungry), and down-regulates insulin and leptin (while also making us insulin resistant), making us more prone to hormonal resistance models that can easily complicate, delay, or even prevent weight loss efforts.

I know what you must be thinking: what do these hormones have to do with sleep?! Well, there is a huge body of literature suggesting that sleep quality and quantity is critical for the regulation of each of these hormones. And, while there are many mechanisms to suggest that sleep is critical for our overall health and weight loss, the one that I believe most directly contributes to weight problems is that lack of sleep directly impacts the satiety of hunger hormones. To put it simply, not getting enough sleep up-regulates ghrelin (making us more hungry), and down-regulates insulin and leptin (while also making us insulin resistant), making us more prone to hormonal resistance models that can easily complicate, delay, or even prevent weight loss efforts.

The research is so strong that irregular findings of these hormones has even been proposed as an indicator for sleep disorders! Clearly, the amount and quality of sleep you get is highly related to your satiety hormone regulation. While this is important for all of us, I think especially about those people who have struggled with long-term maintenance of weight loss and other metabolic problems. Could the missing link be committing to permanent changes in your sleep pattern?

Inflammation

Inflammation

While hormonal regulation is key for weight loss and maintenance, we must also consider the effect that sleep has on inflammation (especially since that’s one of our three main goals for healthy weight loss!). This one is going to be no surprise: disrupted sleep is absolutely associated with increased systemic inflammation. “Inflammation” is a general term used by the medical community to describe a response from the immune system. The immune system is an incredibly complex, fine-tuned machine that allows our body to respond to an overwhelming diversity of microbes to fight off infections. When we talk about systemic inflammation, we’re referring to a non-specific immune reaction that has the immune system “on alert” all the time.

This reaction includes the release of pro-inflammatory chemical messengers called cytokines from the “angry” tissue (this is often our gut, which can become inflamed relatively easily, especially when we are eating outside of the Paleo template); production of the acute-phase reactants in the liver (including C-reactive protein, the blood clotting factor fibrinogen, and others); and elevation of certain blood markers such as glucose and lipids, which are intended by the body to be used to fight the faux infection (but then end up staying in our blood, causing all kinds of unpleasant dysregulation). ALL of these factors can make it more difficult for us to lose weight (recall how the body wants to be in a chilled-out, “safe” place, metabolically-speaking. Inflammation is not that time.). Basically, we really want to dampen inflammation as much as possible to promote healthy weight loss.

Believe it or not, just plain old “not getting enough sleep” (a common practice for so many of us!) causes inflammation. Scientists have measured this in a few ways. A variety of studies evaluating the effects of acute sleep deprivation (typically by restricting sleep to 4 hours per night) for several consecutive nights (on average, 3 to 5 days) have shown increases in markers of inflammation and the numbers of white blood cells in the blood. Specifically, even just three consecutive nights of inadequate sleep can cause an uncontrolled inflammation response (as in the figure above). We can see similar effects of this even from a common practice amongst young people: “pulling an all-nighter.” Even just one night of lost sleep (measured as going at least 40 hours without sleep) causes inflammation in young, healthy people. Pulling a single all-nighter dramatically increases markers of inflammation in the blood, including C-reactive protein and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Studies that evaluated not just sleep deprivation but also recovery after sleep restriction (with the idea of simulating a typical workweek, where someone might get less sleep for 4 or 5 nights straight and then try to make up for it on the weekend) have also shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokine known to stimulate Th17 cell development persists for at least two days after increasing sleep to 8 hours per night, even though other markers of inflammation have recovered. This means that even if you try and “catch up” on your sleep during the weekend, the stimulation to the immune system keeps going–unfortunately, sleep debt recovery just isn’t a 1:1 ratio: we have to sleep more to make up for it. If we follow this stereotypical pattern of not getting enough sleep during the week and sleeping in on the weekend, the consequences are pretty clear: we still run the risk of cumulatively causing detrimental changes in the immune system (overactive Th17 cells are strongly implicated in many autoimmune diseases). Certainly, we can recover from lack of sleep, but it takes persistence, consistency, and commitment (even, or perhaps especially, during the week!).

The relationship between sleep and inflammation isn’t just applicable to short sleep duration or sleep deprivation; it’s also highly linked to interrupted sleep (also called sleep fragmentation and applies to low sleep quality, etc.). Studies in mice have shown that just one day of fragmented sleep led to a significant increase in stress hormones and several inflammatory markers’ (like cytokines) genetic expression in critical areas of the body for health: fat tissue, the heart, and the hypothalamus. These are all especially related to hormones (including the satiety ones and others that we’ll discuss in Parts 3 & 4), which we know are critical for sleep AND for overall health! Indeed, the results seems to be very clear when it comes to this topic; even when looking at general sleep quality, participants have been seen to have elevated c-reactive protein (the most widely-used marker of systemic inflammation).

There are two consequences of the inflammatory response seen in worsened sleep patterns: when our immune system is overactive, we are more likely to develop inflammatory diseases or flares of autoimmune diseases; and on the flip side of that, our immune system may not be able to respond to disease properly (and yes, that’s as much of a problem as it sounds like!). Interestingly, it looks like our specific reaction is age-dependent: younger adults (18-39 years old) are more likely to have an inflammatory condition like irritable bowel disease develop, whereas older adults (60+ years old), whose immune systems tend to be less responsive in general, have weakened capacity to respond to infection. Not to mention, elevated inflammatory markers are associated with a host of health concerns, including cardiovascular disease and cancer. In fact, this elevated inflammation has been described in the literature as a major explanation for the link between short sleep patterns and mortality (see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!)!

So, what do we do with all this information? Sleep more! If sleep is one of your trouble areas, I happen to have the resource for you! My epic online program Go to Bed is chock-full of additional scientific details plus dozens of tips and tricks to improve sleep quality and quantity.

Compared to sleep, the next lifestyle factor is more straightforward, but I wanted to mention sleep first, because it’s so often overlooked and sacrificed before anything else! Next, let’s examine the ways that movement can accelerate weight loss (and how it can actually hinder it).

Steps (Physical Activity)

Alright, you caught me – I totally called this section “steps” just to make it an ‘S’ word. But, we can’t overlook the fact that getting a variety of physical activity (and really, a variety of physical activities, including getting enough steps) is essential for weight loss. There are a few mechanisms at play here. Most importantly (and probably the most obviously), regular exercise is one way to make sure that we create a natural caloric deficit, because moving our bodies burns calories. An important aspect of this is to not overconsume calories as a result of training, which can sometimes be difficult to do! Exercise upregulates hunger hormones, so resisting the post-gym pig-out can be tough. I suggest having a snack that includes carbohydrates and protein to consume after a workout; this will satisfy the craving and provide the fuel to build new muscles (yay!).

Alright, you caught me – I totally called this section “steps” just to make it an ‘S’ word. But, we can’t overlook the fact that getting a variety of physical activity (and really, a variety of physical activities, including getting enough steps) is essential for weight loss. There are a few mechanisms at play here. Most importantly (and probably the most obviously), regular exercise is one way to make sure that we create a natural caloric deficit, because moving our bodies burns calories. An important aspect of this is to not overconsume calories as a result of training, which can sometimes be difficult to do! Exercise upregulates hunger hormones, so resisting the post-gym pig-out can be tough. I suggest having a snack that includes carbohydrates and protein to consume after a workout; this will satisfy the craving and provide the fuel to build new muscles (yay!).

Before we get started on this topic, I wanted to make sure to note: research has demonstrated that exercise alone is not enough to induce spontaneous weight loss (meaning that no other factors were changed). So, while exercise contributes to our three goals to promote weight loss, we can’t spend endless hoursat the CrossFit box without also altering other behaviors (which I’ve outlined in detail in this post and the others in this series).

However, it’s almost impossible to discuss exercise without pulling apart the different types to discuss them individually. We know that the different types of exercise have differential effects on the body, and they have been studied separately in the scientific literature. Let’s go through the different types of exercise so that we can discuss how they independently contribute to weight loss.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise is essentially the scientific way of saying “cardio.” From a scientific perspective, aerobic exercise involves cellular metabolism that utilizes oxygen. Really, this is “normal” human metabolism: aerobic exercise is just higher intensity activity, so it involves the utilization of the stored glucose (as glycogen) in our muscles, and that is the enhanced caloric burn that we experience with this type of exercise (in fact, we don’t burn calories during anaerobic exercise… but we’ll get to that later). What this translates to in a workout scenario is low to moderate activity that involves elevated heart rate, respiration rate, and (almost always) sweating. Notably, extended periods of aerobic exercise utilize our available glycogen stores and promote the release of stored fatty acids; this is the basis for arguing that fasting exercise promotes weight loss (though I’m not sure of the effects on hormones, including insulin, so I would recommend proceeding with caution). But, overexertion in the aerobic exercise realm can lead to muscular atrophy, so aiming to keep this type of exercise to less than an hour per day is ideal.

What does aerobic exercise look like? Again, this is going to be our “cardio” type activities, including:

- Fast walking

- Jogging/running

- Swimming

- Rowing

- Cycling

- Kickboxing

- …and anything that gets your heart rate up!

Most team sports that involve any of the above are going to involve aerobic exercise (and joining adult sports leagues is a great way to get more activity and socialization!).

Apart from the obvious caloric-deficit aspect of aerobic training, there are other benefits to engaging in this type of exercise. Countless research studies have demonstrated the metabolic benefit of aerobic activity, specifically during weight loss efforts; these benefits include increased insulin sensitivity and improved liver function. Why does this matter for weight loss? Since insulin acts at fat cells, it’s critical that someone attempting to lose weight aim to be as insulin sensitive as possible. Aerobic exercise improves the functionality of our fat cells and liver, so we know that the fat being released from storage is going to be properly processed and used as energy (rather than being excreted, or, well, not used up at all!). Another benefit: regularly engaging in aerobic exercise reduces inflammation and is generally immune-modulating, meaning that it improves our body’s ability to respond to the appropriate invaders (this is also important for someone with autoimmune disease, of course). Finally, regular aerobic exercise makes us more resilient to stress (meaning cortisol release is more regulated) and improves cognitive function, making it easier for us to make the right choices in regards to food and lifestyle.

So, what do we do with this information? Evidence overwhelmingly suggests that activity that includes elevated heart rate is critical for metabolic and immune system support during weight loss. However, as I note in Balancing Physical Activity and Rest: How Do We Get It Right? and Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut, overdoing exercise can have critical consequences. I recommend making sure to get regular aerobic activity, at least three days per week but not more than 5 days. How much? I would say to exercise “to tolerance,” meaning that you should leave your workout feeling drained but not exhausted, sweating but not staggering, and able to continue with your daily activities as normal (and this varies from person to person). If you need to nap because you had a hard workout (or hop yourself up on lots of caffeine or sugar to keep yourself going), chances are you both need to dial back the intensity and work on sleep!

Now, I know my heavy lifters are probably huffing and puffing at this information. There are some myths in the weightlifting community regarding the supposed ability of weight training (also known as anaerobic exercise, as we’ll discuss below) to burn tons of calories. While heavy lifting certainly increases heart rate, it doesn’t do so for extended periods of time, and thus we can’t consider it to be a classical aerobic activity. There are benefits of BOTH kinds of exercise (and, spoiler alert: we totally combine both types in certain activities, like CrossFit), but ignoring aerobic activity in favor of solely lifting weights is not an evidence-supported approach to weight loss.

But, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ignore the weights! Let’s discuss anaerobic exercise, shall we?

Anaerobic Exercise

Anaerobic Exercise

Anaerobic exercise is the other main type of exercise. An-aerobic means that cellular metabolism is taking place without oxygen. Like aerobic metabolism, this type of cellular metabolism is totally normal; it is just used by different tissues and under specific conditions. Specifically, fast-twitch muscle, which is used for sprinting and resistance training (weight lifting), utilizes this type of metabolism. Why? It allows for faster movements and provides energy more quickly. The down side is that the byproduct, lactic acid, is created by the pathway and can build up in tissues (this is actually what causes the classic “burn” that we experience during exercise). Because anaerobic metabolism is a limited system, the limit of true anaerobic activity is only about 4 minutes. And, because anaerobic metabolism does not utilize glucose the same way that aerobic metabolism does, we don’t understand how this type of activity specifically contributes to calories burned.

The classic example of anaerobic training is weight lifting (and this means more than body weight exercises. Think squats, bench press, barbell curls, etc.). But, as I mentioned before, anaerobic exercise is also typical in sprinting activities (like running a 100 meter dash or racing a bicycle as fast as possible) and in intensive body-weight exercise like jumping and climbing. At minimum, some kind of anaerobic activity should be incorporated into our fitness routine. I recommend programs like CrossFit that incorporate a varieties of implements and movements, but all of the tools are available at a regular gym if CrossFit feels intimidating or is cost-prohibitive.

So, all of this to say that engaging in anaerobic activity is vastly different. And, while some of the benefits of this activity overlap with that of aerobic (including the metabolic benefits, which are ultra important!), there are independent reasons to engage in high-intensity, anaerobic activities. Specific to weight loss, we see an increase in the release of stored fat immediately after anaerobic exercise (and yes this is totally a big deal). Plus, resistance training increases our lean muscle mass. Why does this matter? Relative to fat cells, muscle cells burn much more energy (in part because muscles make us, well, move, but also because fat cells’ job is to use as little energy as possible – they’re supposed to be storage, after all!). So, when someone gains muscle mass, their metabolic rate goes up, even if they haven’t lost any fat mass. For that reason alone, adding weight training focused on building muscles is essential for long-term weight loss success and especially maintenance.

All of this information might be overwhelming. Thinking about this from a Paleolithic, evolutionary biology perspective, we can posit that hunter-gatherers were engaging in a blend of both types of energy. Running, climbing, jumping, carrying… all of these activities were essential to our survival at one point. And, research confirms that the movement patterns of modern-day hunter-gatherers are wildly different (get it? Ha ha) from ours in developed countries. I believe that engaging in exercise that accesses both types of cellular metabolism is the key to gaining the most benefit from movement, including advances in weight loss. But, spending time in the gym, CrossFit box, or yoga studio isn’t the only way that we should incorporate movement into our days. We need to take breaks from our sedentarism.

Sedentary Breaks

Sedentary Breaks

Many of us think we can cancel out an otherwise sedentary lifestyle (sitting at our desk job, commuting in the car, watching TV, and spending way too much time on Facebook) by going to the gym a few times per week and breaking a sweat. In fact, it’s common to think of exercise as a sort of “payment” to put in so we can veg out on the couch afterward (eating whatever food we’ve “earned”) and not feel guilty about it.

It’s true that regular exercise comes with a number of benefits and is indispensible for staying healthy (we just went through a huge list!). But, a growing body of research is showing that it’s not just the absence of exercise that makes sitting an issue. Sitting itself, especially for long periods, could thwart our weight loss efforts (or at least present as another road block to optimizing our success). The theory behind this harkens back to the logic I mentioned above – we just aren’t meant to spend our days sitting, let alone in chairs. Historically, humans have been active throughout the day, but many of our modern lives just aren’t permissive of that level of activity.

And unfortunately, you can’t make up for sitting all day by giving 110% at CrossFit for an hour in the evening (but wouldn’t that be nice?!).

In fact, the scientific literature has been churning up data that should have all of us rethinking our sitting habits. Previously, a meta-analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine pooled the results of 47 studies on sedentary behavior, the largest study of its kind to date. Across the board, prolonged periods of sitting were linked to higher risk of heart disease (both incidence and death), cancer (both incidence and death), type 2 diabetes, and death from all causes. So, this goes way beyond weight loss.

Even more alarming, the meta-analysis showed that regular exercise did not wipe out the harmful effects of extended sitting. Although people who didn’t exercise and also had sedentary lifestyles fared the worst overall, people who exercised on top of spending long periods sitting down still faced higher risk of death and disease, relative to those who were more active throughout the day. That means that no matter how many buckets of sweat you lose at CrossFit each week, if you spend the rest of your time sitting down and not moving, you’re still putting yourself in danger (and yes, CrossFit is a good example here, because it combines the aerobic and anaerobic activity that we discussed above!).

Researchers are still trying to understand the exact mechanisms that make sitting such a hazard for our health. But, we have enough evidence from animal models and human experiments to start piecing the puzzle together.

The biggest issue is the effect of inactivity on certain metabolic processes in your body, especially in your muscles. Prolonged sitting can suppress the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme involved in lipid metabolism, and in turn contribute to high triglycerides and low HDL. Likewise, the lack of muscle contraction that happens when you sit for a long time can reduce glucose uptake and contribute to elevated blood sugar. The cellular changes from sitting happen very quickly (and are improved as soon as you stand up), so even one day of extreme inactivity can be a detriment. All of these problems start setting the stage for a variety of chronic diseases.

A growing body of scientific literature shows that moving around for just 2 minutes out of every 20 minutes that you would be otherwise completely sedentary has tremendous health benefits. This means that repeatedly setting a 20 minute timer and then getting up and walking around for 2 minute throughout your work day can completely negate the health detriment of prolonged sitting. There are also devices like the FitBit and Apple Watch that can be set to remind us to get up and move around at least once an hour.

Avoiding sedentarism however we can could be a huge step in our weight loss attempts. The bottom line is that moving around at least once per hour has been show to improve our metabolism, including utilization of fatty acids! That means fat loss! There is even clinical trial evidence that utilizing hourly prompts leads to lower BMI in desk workers.

So, while movement is no weight loss magic bullet, there is so much evidence to suggest that prioritizing a lifestyle full of a diversity of movements is huge when it comes to weight loss! Pun intended.

Stress Management

Stress Management

We’ve now seen how much sleep and physical activity can impact our ability to lose weight. Yet, there’s another dealbreaker in the equation, and it’s probably not a surprise: we have to manage our stress if we want to lose weight. And no, this isn’t an optional variable in the equation. We MUST manage our stress, or we WILL NOT lose weight. This is explained by cortisol’s function in the body.

I have discussed the way that cortisol dysfunction occurs in the body in my Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue series, but it is worth a review of how this molecule acts in the body before we move on.

Cortisol is the most significant, commonly-released glucocorticoid in the body. Almost every cell in our bodies have glucocorticoid receptors – so this little molecule can act throughout our entire body! Cortisol has an amazing range of effects in the body, including controlling metabolism, affecting insulin sensitivity, affecting the immune system, and even controlling blood flow. If you’re running away from a lion, all these effects (plus the combined effects of catecholamines and some direct effects of CRH) combine to prioritize the most essential functions for survival (perception, decision making, energy for your muscles so you can run away or fight for your life, and preparation for wound healing) and inhibit non-essential functions (like some aspects of the immune system especially not in the skin, digestion, kidney function, reproductive functions, growth, collagen formation, amino acid uptake by muscle, protein synthesis and bone formation).

Cortisol also provides negative feedback to the pituitary and the hypothalamus. It’s the body’s way of saying, “hey, we got the signal that we’re supposed to be stressed now, thanks, we’re on it!” If the stressful event has ceased (the lion gave up and left), this is what deactivates the HPA axis. Of course, if a stressor is still being perceived (that lion is still there), the HPA axis remains activated. And this is why chronic stress (deadlines, traffic, sleep deprivation, teenagers, divorce, being sick, being inflamed, alarm clocks, bills, and internet trolls) is such a problem: the net effect of cortisol is catabolic, meaning that it prepares the body for action without giving it any opportunity to rebuild! And, as we know, chronic stress can be incredibly long term… like decades. So, the amount of pressure that puts on the adrenal glands to produce cortisol to combat our perceived stressors is magnanimous, and that pressure is what causes adrenal fatigue and can undermine weight loss efforts. Since cortisol increases blood glucose levels, chronically high cortisol can lead to increased storage of fat (plus, that makes it very difficult for us to use the fat already have!). There are other consequences that I discuss in the adrenal fatigue series, including the way that overproduction of cortisol leads to widespread hormonal imbalance and nutrient depletion. That, in turn, can lead to systemic inflammation. Basically, we really want to make sure that we keep our adrenal glands happy and manage our stress!

So, we know that we need to do what we can to improve our cortisol response and manage our stress. I write a lot about this in part 3 of the series, entitled Nutrition & Lifestyle Support for the Adrenal Glands, but there are some honorable mentions that are worth covering here.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a meditation strategy that is by far the best-supported in the scientific literature. Importantly, implementation of MBSR has been shown to improve emotional eating and other factors, making it easier for us to make the right choices about diet and exercise. This strategy implements the technique of noticing thoughts and feelings during a period of stillness; this period might be 5 minutes or as much as an hour (I recommend starting small!). There are many websites and phone apps dedicated to MBSR that could help with stress management on the daily.

Yoga is a marvelous way to incorporate stress management with exercise! I have been a longtime fan of yoga for weight loss and still wholeheartedly recommend it for these reasons. Plus, there are even studies demonstrating its effectiveness in improving BMI, body weight, body fat, and waist circumference!

Self-care exercises like taking a bath, reading a lighthearted or otherwise enjoyable book, getting a professional massage or trading massages with a partner or friend, and even breaking out the adult coloring books (or steal your kids’ coloring books!) have all been shown to reduce perceived stress and dampen our cortisol levels. While losing weight is certainly a task the requires much of our attention, there is considerable value in stepping back and building in some “me time.”

It is really easy to get caught up in our lives, and adding in the steps necessary to lose weight can be really daunting,

Sustainability

Sustainability

I incorporate a lot of recommendations here that are scattered throughout this website. Why? Whether we like it or not, we often have to fine-tune our choices in order to support weight loss. This is a time when, unfortunately, we have to focus on “doing everything right” in a way that’s sustainable (does that sound like an oxymoron? I know.). We can put in ALL this effort and do a HUGE overall of EVERYTHING about our lives… and then have the changes last for just a week, or even just a couple days. For this reason, sustainability is my final ‘S’ suggestion when it comes to lifestyle overhaul: because it is the foundation that keeps every other aspect intact.

When it comes to weight loss, use SMART goals. This approach to goal-setting is the #1 most recognized and supported by psychological and medical communities, and this is the approach recommended by most weight loss counselors. SMART stands for specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based. We can use SMART goals for each of the steps I’ve outlined AND for our overall weight goals! For example, we could have a goal to start eating fatty fish (rich in anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids) at least three times per week, starting next week. This goal is relevant to our weight loss plans, and is specific, measurable, and time-based (and totally attainable!). Setting and reaching goals is a fantastic tool for making weight loss efforts (and then, weight loss maintenance!) sustainable in the long term.

I recommend breaking down the various aspects of healthy weight loss (diet and lifestyle) into a collection of small SMART goals. One goal targeting sleep might be to have a regular bedtime eight hours before your alarm goes off in the morning. Another goal targeting both steps and stress reduction might be to go for a 30-minute walk every day. Another goal targeting creating a caloric deficit might be to have a big salad with dinner every night. And, if those are too big, then start even smaller. Maybe it’s a 20-minute walk Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays, and maybe it’s just making sure there’s at least one vegetable on your plate at every meals. Don’t be afraid to take on these changes iteratively, if that’s a better tactic for long-term sustainability for you.

Before we wrap things up, I want to make sure to note a few more details about making weight loss sustainable. When I talk about weight loss being sustainable, there are a few things I mean:

- It’s based on habit formation, not extreme changes. I’ve written about the science of habit formation before (see Habit Formation and New Years Resolutions, The Power of Journaling for Self-Change), and I think implementing these strategies is absolutely critical when it comes to healthy weight loss. After all, what’s the point if we can’t even keep up these behaviors once our goals have been met?

- The behaviors are enjoyable enough that you’d want to keep doing them. Many people don’t think about this one, but I think it’s just as important as the other aspects of making changes. If you’re miserable with your diet and workout plan, you won’t want to stick to it! Spend some time thinking of a variety of foods and activities that will be (relatively) enjoyable. Plus, engaging in activities that are enjoyable will reinforce habit formation and promote the stress management-oriented benefits of things like exercise!

- All aspects are affordable in the long-term. Before starting a weight loss effort, it might be tempting to join the fanciest gym in town or buy that Vitamix you’ve always wanted or go for 100% local, organic produce and meat (which is awesome, of course, but undeniably more expensive). Well, I challenge you to think about whether these choices are going to support your long-term goal of weight loss, and whether you’ll be able to continue affording them after a month, or a few months, or a year. Don’t let financial decisions be a barrier to making these choices! Everything can be modified to whatever your individual resources are.

Taken together, these approaches will make weight loss behaviors much more sustainable than jumping the gun without a plan or realistic goals. Of course, we want to be able to see our weight loss through, and then we need to be able to maintain the weight change after we’ve lost those pounds! Yes, weight maintenance is a real and daunting challenge, and it includes keeping up with all the behaviors I’ve described in this article.

Putting It All Together

Clearly, we can see that lifestyle is a huge factor when it comes to weight loss, and there are many facets that we can focus on when it comes to lifestyle changes.

So, what happens if we implement all of these concepts and are still struggling to lose weight? Stay tuned for Part 3!

Citations

Belcher BR, Berrigan D, Papachristopoulou A, et al. Effects of Interrupting Children’s Sedentary Behaviors With Activity on Metabolic Function: A Randomized Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):3735-43.

Duvivier BM, Schaper NC, Hesselink MK, et al. Breaking sitting with light activities vs structured exercise: a randomised crossover study demonstrating benefits for glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2016.

Engeroff T, Füzéki E, Vogt L, Banzer W. Breaking up sedentary time, physical activity and lipoprotein metabolism. J Sci Med Sport. 2017.

Koster A, et al. “Association of sedentary time with mortality independent of moderate to vigorous physical activity.”PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037696. Epub 2012 Jun 13.

Levoy E, Lazaridou A, Brewer J, Fulwiler C. An exploratory study of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction for emotional eating. Appetite. 2017;109:124-130.

Mcdonnell MN, Buckley JD, Opie GM, Ridding MC, Semmler JG. A single bout of aerobic exercise promotes motor cortical neuroplasticity. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114(9):1174-82.

Ryan AS, Ge S, Blumenthal JB, Serra MC, Prior SJ, Goldberg AP. Aerobic exercise and weight loss reduce vascular markers of inflammation and improve insulin sensitivity in obese women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):607-14.

Salvadori A, Fanari P, Marzullo P, et al. Short bouts of anaerobic exercise increase non-esterified fatty acids release in obesity. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53(1):243-9.

Thorogood A, Mottillo S, Shimony A, et al. Isolated aerobic exercise and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):747-55.