The idea that a high intake of refined sugar could be contributing to our obesity and chronic disease epidemics is nothing new. But, one sweetener has gotten a particularly bad rap: high fructose corn syrup (HFCS)! Many of us go out of our way to avoid foods that list it as an ingredient (along with sodas and sweets, it’s often found in pasta sauces, salad dressing, condiments, and other sources we might not expect). So, what exactly makes this sweetener a hazard to our health?

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

The Problem with Fructose

The Problem with Fructose

The biggest concern with high fructose corn syrup is its huge contribution of fructose to our diets. In the food industry, two main forms of high fructose corn syrup are used: HFCS-55 (which contains 55% fructose) and HFCS-42 (which contains 42% fructose). HFCS-55 provides slightly more fructose than regular table sugar, which gets cleaved into 50% glucose and 50% fructose by our enzymes during digestion.

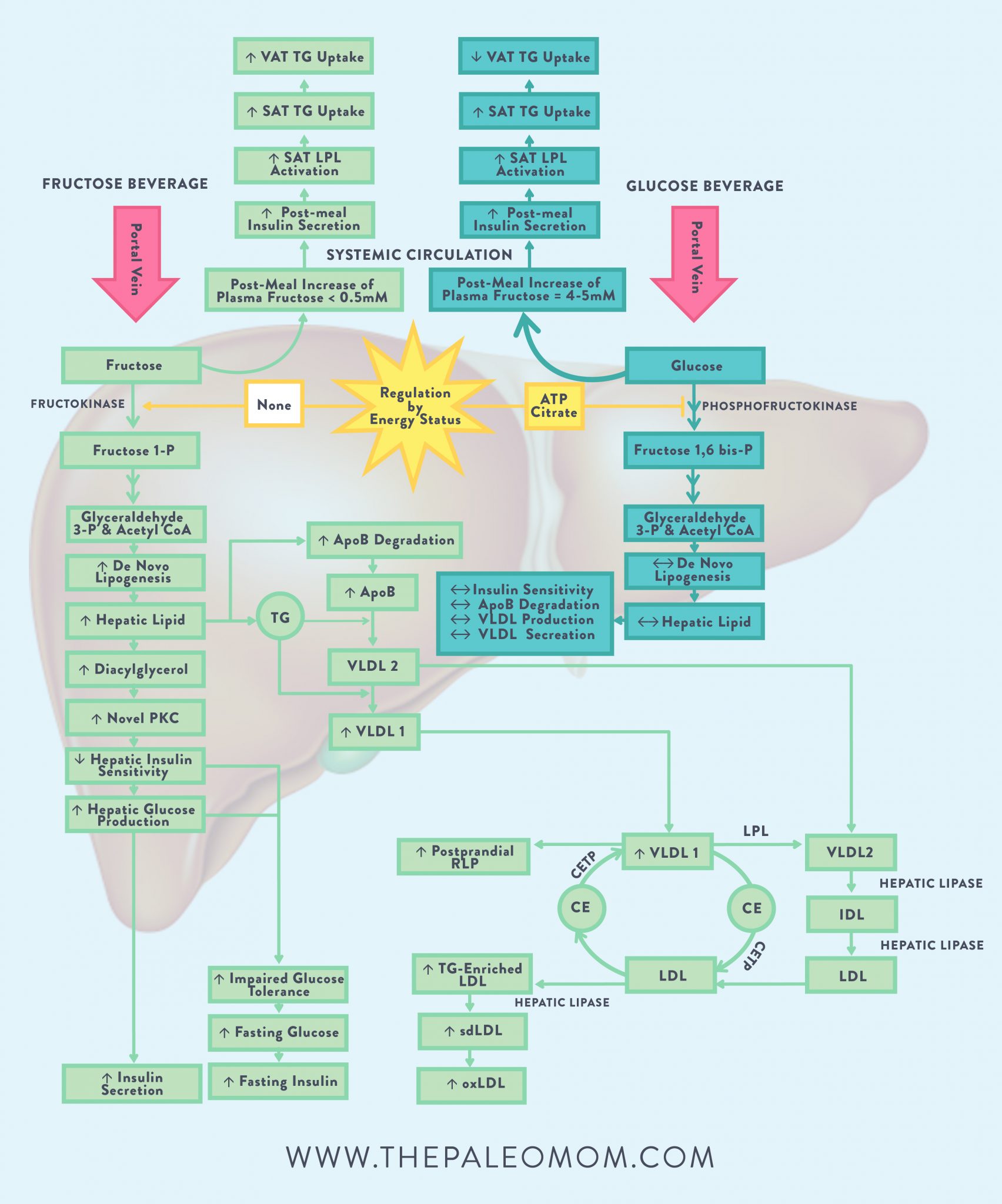

Here’s where the problems begin! Unlike glucose (which is absorbed high up in the digestive tract, and can be used as energy by virtually every cell in our bodies), fructose is poorly absorbed in our intestines and can only be broken down in the liver. Whereas glucose can enter cells through insulin-dependent GLUT4 transporters, fructose uses a different transporter (GLUT5) that’s absent in most cells. So, the fructose we ingest from high fructose corn syrup is unable to provide cellular fuel throughout our bodies in the same way glucose does.

Because of its unique metabolic pathway, high intakes of fructose lead to a rise in triglycerides in our blood (fructose can enter the pathways for glycerol, which combines with three fatty acids to form the backbone for triglycerides). Fructose metabolism also leads to the formation of uric acid and free radicals, which can deactivate nitric oxide production and damage cell structures and DNA, respectively. And, when the liver receives a big package of fructose, glucose uptake pathways get disturbed, and the rate of de novo lipogenesis (the enzymatic pathway that converts carbohydrates into fat) increases. In case all of that isn’t bad enough, fructose can also help transport endotoxins (harmful components in the outer membrane of certain bacteria) across the gut barrier, though we aren’t sure yet whether it’s a result of a direct affect on intestinal permeability or from changes in the composition of our gut microbiome. (By now, it should be abundantly clear that we really want to treat our guts well if we want to stay healthy, happy, and alive!) See also Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems? and Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm?.

Another difference between glucose metabolism and fructose metabolism is that fructose doesn’t stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. This might sound like a good thing on the surface, but the result is a smaller rise in the hormone leptin and less suppression of ghrelin—creating a situation where our brain doesn’t get the memo that we’ve eaten enough and can put the fork down. So, HFCS (and other sweeteners that yield a hefty fructose bomb) may actually cause us to feel hungrier and less satisfied, leading us to eat more than we need! (See The Hormones of Hunger)

As a result of these unique features of fructose, excessive intakes have been linked to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver, obesity, diabetes, and other chronic conditions (all of which increased hand-in-hand with our consumption of high fructose corn syrup: in the two decades between 1970 and 1990, consumption of high fructose corn syrup increased by over 1000%). Although controversy still exists about correlation versus causation, we have enough understanding of the mechanisms tying fructose to metabolic problems—and a huge stack of scientific research studying those mechanisms—to make the “causation” argument pretty convincing! See also Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?, Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm? and Is It Paleo? Fructose and Fructose-Based Sweeteners (I’m looking at you, Agave!).

Is High Fructose Corn Syrup Worse Than Regular Sugar?

Is High Fructose Corn Syrup Worse Than Regular Sugar?

Another hotly debated topic is whether high fructose corn syrup is more harmful than table sugar. Some experts have argued that because table sugar (sucrose) gets metabolized into 50% fructose and 50% glucose in our bodies, there’s not much difference between sugar and high fructose corn syrup containing 55% fructose. Other people point out that high fructose corn syrup contains free (unbound) fructose and free glucose, whereas sucrose is composed of a glucose and fructose molecule chemically bonded together. Could that difference (the presence of free, rather than bound, fructose) cause HFCS to be more metabolically harmful?

There aren’t many studies that look at how free fructose differs from bound fructose after consumption, but the existing research doesn’t give much weight to the “HFCS is worse!” theory. One study of type 2 diabetics found that 35 g of either sucrose or the equivalent amounts of free fructose and glucose produced similar blood sugar and insulin responses. Another study found that HFCS versus sucrose resulted in the same satiety response (as well as the same energy intake at the next meal), refuting the idea that HFCS uniquely encourages excess calorie intake. While we definitely need more research to confirm whether the metabolism of HFCS differs in important ways compared to sucrose (especially when it comes to lipogenesis, fat accumulation in the liver, and inflammation), there currently isn’t enough evidence to make the case that HFCS has different health effects than table sugar. Our best bet is to limit both! Speaking of which…

How Much is Too Much?

The giant fructose load we get from HFCS is definitely concerning, but this is a classic case of “the dose makes the poison.” Fructose occurs naturally in fruit and honey, and our bodies are perfectly equipped to handle it in small amounts. (In fact, small amounts of fructose might even be beneficial, because low doses can reduce blood sugar levels in response to glucose consumption and even improve insulin sensitivity. Plus, unlike HFCS, fruit and honey contain other beneficial nutrients and compounds that can offset some of the negative effects of fructose!) Only recently in history (thanks to the introduction of HFCS in the 1970s, on top of an already-high intake of other refined carbohydrates) has the human diet been able to supply as much fructose as it currently does. For example, we’d have to eat over 11 medium-sized bananas to get the same amount of fructose that’s in a liter of Coca-Cola! By USDA estimates, the average American now consumes almost 25 lbs. of high fructose corn syrup each year, and when it comes to all sources of fructose, the average person gets around 55 grams per day (over 200 calories).

Once we eliminate concentrated sources of fructose like HFCS and switch to Paleo (where our fructose sources come packaged with fiber, micronutrients, and phytochemicals instead of empty calories!), our fructose intake generally drops to much healthier levels (for reference, healthy intake is considered to be anywhere between 10 grams and 40 grams daily). But, just because we avoid HFCS doesn’t mean we’re automatically immune to excessive fructose consumption. Even Paleo-friendly foods like dried fruit, agave syrup (which can be even higher in fructose than HFCS), and honey can drive our fructose intake upwards if we’re not careful. Consuming moderate amounts of fresh fruit (say 2 to 5 servings daily) and small amounts of honey (if desired) is our best bet for getting the perks of fructose-containing whole foods without overdoing it!

Citations

Akgun S & Ertel NH. “The effects of sucrose, fructose, and high-fructose corn syrup meals on plasma glucose and insulin in non-insulin-dependent diabetic subjects.” Diabetes Care. 1985 May-Jun;8(3):279-283.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Basciano H, et al. “Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia.” Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005 Feb 21;2(1):5.

Bray GA, et al. “Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Apr;79(4):537-43.

Bray GA. “How bad is fructose?” Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Oct;86(4):895-896.

Tappy L & Lê KA. “Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity.” Physiol Rev. 2010 Jan;90(1):23-46.

“US Consumption of Caloric Sweeteners: Table 52.” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Accessed August 6, 2016.

Walker RW, et al. “Fructose content in popular beverages made with and without high-fructose corn syrup.” Nutrition. 2014 Jul-Aug;30(7-8):928-35.

White JS, et al. “High-Fructose corn Syrup: Controversies and Common Sense.” Am J Lifestyle Med. 2010;4:515–520.