SCIENCE SIMPLIFIED:

- The therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets comes at a cost — it’s important to know that ketogenic diets can harm your health before you decide whether or not to “go keto”

- New studies show that ketogenic diets reduce diversity of the gut microbiome — this is very bad because diversity is a measure of how healthy a gut microbiome is, and our gut bacteria are really, really important for our health

- Ketogenic diets also reduce the growth of key probiotic bacteria (Bifidobacterium and Roseburia species, and Eubacterium rectale)

- The effects of keto on the gut microbiome might be one way that ketogenic diets work in epilepsy and multiple sclerosis, but also why ketogenic diets can cause so many problems in people using it for other reasons, like losing weight

RELATED READING:

- Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised

- What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

Just because a diet is popular does not mean that it lives up to its claims nor does it mean that it’s safe! Case in point: ketogenic diets. I have been a loud voice of dissent within the Paleo and alternative health communities for about the last five years, expressing my deep concern about the documented inherent risks of following a ketogenic diet, while proponents issue statements that amount to little more than propaganda, expounding on the potential benefits yet dismissing the vast amount of scientific evidence that draws those results into question and that explains the mechanisms behind how ketogenic diets can cause harm. In reality, ketogenic diets absolutely do show therapeutic potential for some medical conditions (such as refractory epilepsy and multiple sclerosis), but the choice to follow a ketogenic diet requires an informed and careful cost-benefit analysis and close medical supervision.

Today’s post is not designed to relitigate this debate, but I do encourage you to read Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised. Instead, I want to dive deep into one of the risks that ketogenic diets pose that I have not yet discussed in detail: the impact of keto on the gut microbiome!

Up until recently, research on how ketogenic diets impact the human gut microbiota has been extremely limited, leading to lots of speculation without much hard data. Luckily, in the last few years alone, that’s changed! Several studies have come out examining the gut microbiota effects of ketogenic diets, helping us paint a picture of what really happens in our gut when we go keto. And, the findings raise some major red flags.

What Does the Science Show?

First, it’s worth emphasizing that the composition of our gut microbiome affects every system, and indeed every cell, in our bodies. We benefit greatly when we have a diverse gut microbiome, abundant in key protiotic species. See What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?. I am currently writing an entire book on the best foods to eat to support a healthy, diverse gut microbiome, but the quick summary is: plenty of high-fiber and phytonutrient-rich fruits and vegetables (aiming for at 8+ servings of veggies daily and ideally 45-50 grams of fiber) that hit as many fruit and vegetable groups daily as possible—cruciferous vegetables, mushrooms, roots, tubers, alliums, leafy greens, berries, apple family, citrus—as well as nuts and seeds, herbs and spices, peas, extra virgin olive oil, fish, shellfish, honey and bee products, fermented foods, edible insects, tea, coffee, cocoa and bone broth. See also Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome, Why Fish is Great for the Gut Microbiome, Honey: The Sweet Truth About a Functional Food! and watch my recent Paleo f(x) 2019 talk on the microbiome here.

Given how incongruous the tenets of a ketogenic diet are with the above ideal for microbiome health, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that ketogenic diets can dramatically impact the gut. We know from existing research that significant increases in fat and reductions in fermentable substrate (like fiber and resistant starch) shift the intestinal environment and change the food supply reaching our resident microbes (see also Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?, Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses, and The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?). Interestingly, for some of the conditions keto has been shown to benefit (such as epilepsy and autism), the effects are at least partially mediated through gut bacteria. For example, in a mouse model of autism, a ketogenic diet had a distinct antimicrobial effect (causing a significant drop in bacterial abundance) and helped reduce elevated levels of Akkermansia muciniphila, which were abnormally high among the BTBR mice relative to the control animals. Although lower bacterial levels and a reduction in beneficial Akkermansia muciniphila aren’t typically considered desirable for gut health, these changes are associated with improvements in autism symptoms. We also know that in humans, certain antibiotics (such as vancomycin) have led to reduced autism symptoms in children with the disorder, suggesting that the antimicrobial effect of ketogenic diets could mimic that of antibiotics and improve symptoms of autism through similar mechanisms.

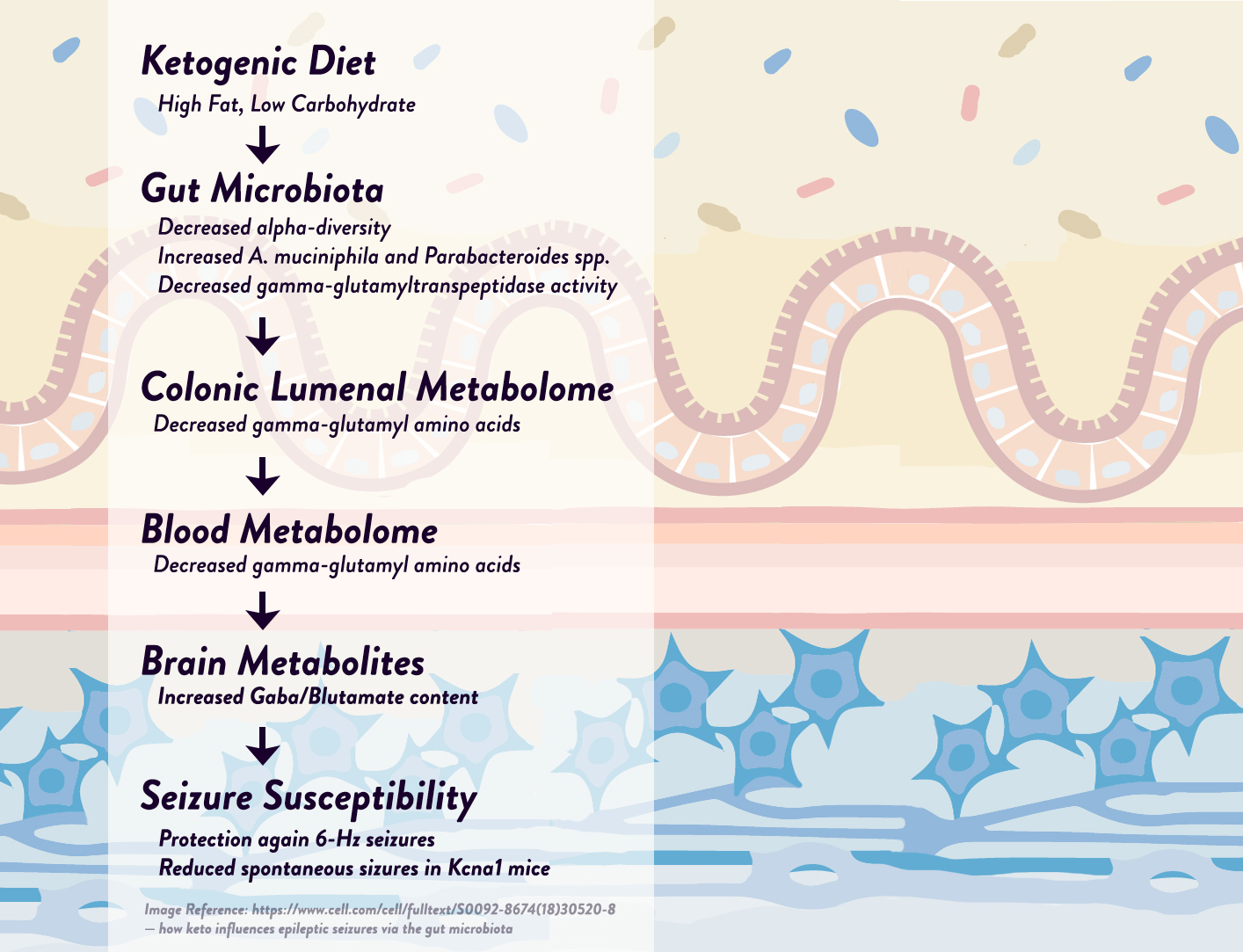

Likewise, using a mouse model of epilepsy, researchers discovered that two specific bacteria—Akkermansia muciniphila and Parabacteroides—were elevated by the ketogenic diet and appeared to be responsible for the diet’s anti-epileptic effects, working synergistically to affect neurotransmitter activity in the hippocampus (the part of the brain that generates many epileptic seizures). More specifically, these two bacteria together—but not individually—were able to reduce levels of gamma-glutamylated amino acids in the gut and blood, in turn raising hippocampal GABA/glutamate levels and reducing the frequency of seizures in the mice. As evidence that the microbiota changes were responsible for the seizure reduction, the researchers tested the ketogenic diet on mice with sterilized microbiomes (either from antibiotic treatment or from being reared in a germ-free environment) and found that the diet was no longer protective against seizures! Although more studies are needed in humans, we do know from earlier research that epileptic infants respond to ketogenic diets with a reduction in seizure frequency and an increase in Prevotella and Bifidobacterium populations, supporting the idea that specific bacteria could have anti-seizure effects in humans as well as mice.

But, while ketogenic-diet-induced changes in the gut microbiota can benefit very specific medical conditions, the overall effect on gut health isn’t so rosy. As we just touched upon, the effects of ketogenic diets on epilepsy—consistent throughout multiple studies—includes a drop in bacterial diversity, a near-universal hallmark for a less-healthy, less-resilient microbiome. Here’s what the other available literature has to say!

In a study of 12 children with therapy-resistant epilepsy, three months of consuming a ketogenic diet resulted in a significant drop in some important bacteria groups, including Bifidobacterium (a genus of probiotics that produce vitamins, regulate the gut’s microbial homeostasis, help prevent pathogens from infecting the gut, boost immune function, and much more!). Bifidobacteria levels plummeted from an average relative abundance of 15.8% before the ketogenic diet to only 3.9% after three months. And, two species in particular took a big hit: Bifidobacterium longum (which helps mediate immune function and promotes good digestion) dropped 3.3-fold, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis (which synthesizes vitamin B12, thiamin, vitamin B6, and folic acid) dropped 16-fold. Likewise, the ketogenic diet resulted in lower levels of Eubacterium rectale (a major producer of short-chain fatty acids) and an increased abundance of Escherichia coli (which includes several pathogenic strains famous for causing food poisoning, and whose overgrowth has been linked to Crohn’s disease).

In this study, the researchers noted that the significant drop in Bifidobacterium and Eubacterium rectale could result in lower levels of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and lactate (which are products of the bifid shunt—the unique fermentative pathway used by bifidobacteria), in turn reducing the acidity of the intestine. Maintaining a low pH in the gut is one of the ways our body helps prevent intestinal infection with pathogens (many of which are acid-sensitive), and this could explain why the compositional changes induced by a ketogenic diet included a rise in E. coli abundance.

In another study, researchers looked at the effects of a ketogenic diet on patients with Glucose Transporter 1 Deficiency Syndrome (GLUT1-DS), a rare metabolic disorder that prevents glucose from crossing the blood-brain barrier. Along with consuming a classical ketogenic diet (a 4:1 ratio of fat grams to carbohydrate plus protein grams), the participants were given vitamin and mineral supplements to prevent micronutrient deficiencies, which can independently alter the gut microbiota composition. After three months eating keto, the biggest change in the participants’ microbiota was a significant rise in Desulfovibrio, a genus of sulfate-reducing bacteria that’s been found in relatively high concentrations in people with inflammatory bowel disease. (Desulfovibrio can cause inflammation in the gut mucosa by activating immune responses and producing hydrogen sulfide, which acts as a pro-oxidant and can be toxic to cells!)

Intriguingly, the rise in Desulfovibrio may be specifically linked to increased intake of dairy fat, which went up substantially for most participants in this study (average saturated fat intake increased from 8.4% of calories at baseline to 23.5% on the diet, largely from butter, cream, cheese, and other high-fat dairy foods). In mice, researchers have shown that saturated fat from dairy (but not polyunsaturated fat from safflower oil) promotes the taurine conjugation of bile acids, which in turn increases the availability of organic sulfur that bacteria like Desulfovibrio use. These altered gut conditions lead to an expansion of sulfate-reducing microbes, and a potentially higher risk of inflammatory gut disorders. So, when it comes to ketogenic diets, milk-derived fats may induce a shift in bile acid composition that then promotes the growth of Desulfovibrio! We’ll need more studies to determine whether other sources of saturated fat have a similar effect.

Interestingly, a longer-term study in patients with MS showed something unique among the available literature: an initial drop in microbiota response to ketogenic eating, followed by a recovery to normal levels. In this study, MS patients were put on diets designed to achieve modest ketosis (at least 500 μmol/L ß-hydroxybutyrate in the blood and ≥500 μmol/L acetoacetate in the urine) for a total of six months. (This diet was only 69% calories from fat (21% from protein and 10% from carbohydrates) which is on the cusp for achieving sustained ketosis, compared to “classic” ketogenic diets having 75-80% calories from fat).

Up until the 12th week of the study, all groups of bacteria other than Akkermansia decreased, leading to significant drop in total bacterial concentration and a reduction in bacterial diversity from 48% to 35% (with some groups of formerly present bacteria falling below the detection level). The magnitude of these changes were similar to the effects of antibiotics! Around week 12 of the study, though, bacterial concentrations started to rise again, and near the six-month mark, they were significantly higher than the concentrations the MS patients had at baseline (and were similar to the average bacterial concentrations seen in healthy controls).

So, does this mean ketogenic diets will restore a healthy microbiome as long as we stick to them long enough? Not so fast! MS patient started out with unique microbiomes (low in biofermentative bacteria, relative to healthy controls), making it hard to extrapolate the findings to other groups of people, and the study was relatively small (only 10 participants had their microbiota analyzed). Likewise, this study was relatively higher in protein and carbohydrate (150 grams per day combined) than classical ketogenic diets with a higher proportion of fat, which could potentially play a role in the results. What’s more, studies of similar length with epileptic patients didn’t see a recovery in concentration or diversity after adhering to ketogenic diets for longer periods of time. At best, this study suggests that ketogenic diets may be specifically helpful to MS patients, but we can’t assume everyone else will be so lucky!

What about for people who don’t have specific medical conditions that keto is known to benefit? We can get some clues about this by looking at weight-loss studies. One trial placed participants on two different weight-loss diets lasting four weeks each (a moderate carbohydrate diet with 164 grams of carbohydrate per day, and a ketogenic diet with 24 grams of carbohydrate per day), and found that the ketogenic diet phase brought the greatest reduction in the Roseburia and Eubacterium rectale group, which plays a key role in producing butyrate and protecting colonic health. Likewise, bifidobacteria levels decreased more dramatically when participants were eating the ketogenic diet versus the moderate carbohydrate diet. The preponderance of evidence suggests these changes are a net negative.

What Do We Make of it All?

Although more research is definitely needed to clarify (and expand on!) the findings we currently have, there are a few observations we can make so far.

First, the good news. For certain medical conditions, especially autism and epilepsy and potentially MS, the effects of a ketogenic diet on the microbiota composition seem to be beneficial—at least for the condition in question. Even when changes occur that are typically considered detrimental, such as a drop in diversity, other changes seem to specifically mediate pathways that contribute to disease, making the pros arguably outweigh the cons.

But, for people who aren’t treating a specific medical condition that ketogenic diets have already been shown to benefit, there’s virtually no evidence that going keto will do your microbiota any favors. The promotion of a less acidic colonic environment (due to reduced fermentation of plant-derived substrates, and subsequently a lower production of short-chain fatty acids) has the potential to be an issue in long-term ketogenic diets. According to Jeff Leach, microbiome researcher and founder of the Human Food Project, a shift in pH and available substrate creates an environment where acid-sensitive pathogens can flourish (including members of Escherichia, Salmonella, Helicobacter, and Vibrio), while also starving important butyrate producers like Eubacterium and Roseburia. Combined with the effects of a higher saturated fat intake on gut barrier integrity, the microbial community shaped by ketogenic diets is likely to increase gut permeability and ultimately shift the microbiome to a state of dysbiosis. The promotion of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the gut is a serious concern, especially with ketogenic diets that rely heavily on dairy fats, since hydrogen sulfide (the final product of sulfate-reducing bacteria like Desulfovibrio) is known to harm the gut mucosa and promote inflammation through multiple mechanisms. We also know that when gut bacteria have a short supply of carbohydrate, they turn to alternative energy sources like amino acids, causing them to produce metabolites that may be harmful to human health.

The evidence we have so far suggests that drastically decreasing carbohydrate intake (particularly fiber and resistant starch) will reduce populations of some very important bacteria, and a concurrent increase in fat (especially saturated fat) can alter systemic endotoxin levels, intestinal permeability, inflammation, and microbiota composition. Collectively, the elements that define ketogenic diets seem to be a lethal combination for our gut health.

This isn’t to say that ketogenic diets don’t have very real, significant benefits for many people, or that everyone who goes keto will automatically face severe gut health issues. However, being realistic about the potential harm that ketogenic diets can bring is important in order to safeguard against future problems (again I encourage you to read Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised). Supplementing with prebiotic foods and potentially certain probiotic bacteria, consuming a diverse array of fibrous plant foods, keeping saturated fat intake (especially dairy fat) at reasonable levels (see Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?), and taking other measures to optimize gut health (including lifestyle factors like adequate sleep, stress management, and healthy activity levels, see The Paleo Lifestyle) may help take the edge off some of the gut microbiota risks involved with ketogenic eating. But, the best solution for many people may simply be eating a nutrient-dense diet that retains a higher level of fiber- and phytochemical-rich carbohydrate foods to support a healthy microbial community in our gut (see The Importance of Vegetables and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body).

This isn’t to say that ketogenic diets don’t have very real, significant benefits for many people, or that everyone who goes keto will automatically face severe gut health issues. However, being realistic about the potential harm that ketogenic diets can bring is important in order to safeguard against future problems (again I encourage you to read Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised). Supplementing with prebiotic foods and potentially certain probiotic bacteria, consuming a diverse array of fibrous plant foods, keeping saturated fat intake (especially dairy fat) at reasonable levels (see Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?), and taking other measures to optimize gut health (including lifestyle factors like adequate sleep, stress management, and healthy activity levels, see The Paleo Lifestyle) may help take the edge off some of the gut microbiota risks involved with ketogenic eating. But, the best solution for many people may simply be eating a nutrient-dense diet that retains a higher level of fiber- and phytochemical-rich carbohydrate foods to support a healthy microbial community in our gut (see The Importance of Vegetables and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body).

Citations

Brinkworth GD, et al. “Comparative effects of a very low carbohydrate, high fat and high-carbohydrate, low-fat weight loss diets on bowel habits and feacal short chain fatty acids and bacterial populations.” British J Nutri. 2009;201(10):1493-1502.

Devkota S, et al. “Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in Il10-/- mice.” Nature. 2012 Jul 5;487(7405):104-8. doi: 10.1038/nature11225.

Earley H, et al. “A Preliminary Study Examining the Binding Capacity of Akkermansia muciniphila and Desulfovibrio spp., to Colonic Mucin in Health and Ulcerative Colitis.” PLoS One. 2015 Oct 22;10(10):e0135280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135280. eCollection 2015.

Ellerbroek, A. “The effect of ketogenic diets on the gut microbiota.” Journal of Exercise and Nutrition. 2018;1(5).

Leach, J. “Sorry Low Carbers, Your Microbiome is Just Not That Into You.” Human Food Project. 26 June 2013. http://humanfoodproject.com/sorry-low-carbers-your-microbiome-is-just-not-that-into-you/

Lindefelt M, et al. “The ketogenic diet influences taxonomic and functional composition of the gut microbiota in children with severe epilepsy.” NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019 Jan 23;5:5. doi: 10.1038/s41522-018-0073-2. eCollection 2019.

Newell C, et al. “Ketogenic diet modifies the gut microbiota in a murine model of autism spectrum disorder.” Mol Autism. 2016 Sep 1;7(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0099-3. eCollection 2016.

Olson CA, et al. “The Gut Microbiota Mediates the Anti-Seizure Effects of the Ketogenic Diet.” Cell. 2018 Jun 14;173(7):1728-1741.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.027. Epub 2018 May 24.

Swidsinski A, et al. “Reduced Mass and Diversity of the Colonic Microbiome in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Their Improvement with Ketogenic Diet.” Front Microbiol. 2017 Jun 28;8:1141. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01141. eCollection 2017.

Tagliabue A, et al. “Short-term impact of a classical ketogenic diet on gut microbiota in GLUT1 Deficiency Syndrome: A 3-month prospective observational study.” Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2017 Feb;17:33-37. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.11.003. Epub 2016 Dec 18.

Xie G, et al. “Ketogenic diet poses a significant effect on imbalanced gut microbiota in infants with refractory epilepsy.” World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Sep 7;23(33):6164-6171. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6164.

Zhang Y, et al. “Altered gut microbiome composition in children with refractory epilepsy after ketogenic diet.” Epilepsy Res. 2018 Sep;145:163-168. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.015. Epub 2018 Jun 28.