Could there possibly be a more controversial topic than how many carbs we should be eating?! One of the perks of following a Paleo framework is that when we maximize nutrient density (see The Importance of Nutrient Density) and eat high-quality foods from both the plant and animal kingdom, other elements of diet, like macronutrient ratios, tend to fall into place without us needing to obsessively count fat or carb grams. Still, considering how much bad press carbohydrates tend to get (as well as the tendency for the media—and even some leaders within the Paleo movement itself—to mis-portray Paleo as being low carb), a great deal of confusion exists surrounding optimal carb intake. What’s the scoop?

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- What Is a Carbohydrate?

- Carbohydrates Stimulate Insulin Release

- Determining Optimal Carbohydrate Intake

- Hunter-Gatherer Carb Intakes

- Carbohydrate Quantity vs. Quality

- Glycemic Load vs. Glycemic Index

- Eating Carbohydrates to Get Enough Fiber

- Starch and the Microbiome, Another Reason to Up Carbs

- The AMDR and Balanced Macros

- But, What About Low-Carb and Ketogenic Diets?

- 8+ Veggies & 3+ Fruit Daily

- If Sugar is Bad, How About Sugar Substitutes?

- Healthy Paleo Carbs to Choose From

- So, How Many Carbs Should We Eat?

- Citations

What Is a Carbohydrate?

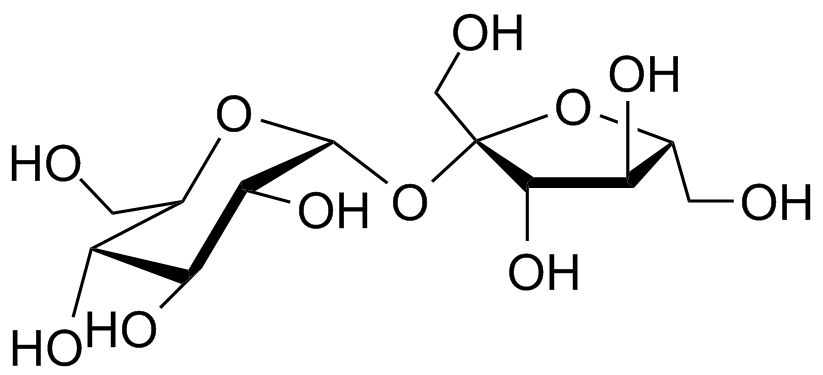

Carbohydrates are a class of organic molecules, made up of sugar molecules, or saccharides, as the basic structural components. Carbohydrates are relatively simple molecules composed of carbon atoms, oxygen atoms and hydrogen atoms (including hydroxyl groups, one oxygen and one hydrogen bound together), and a general formula of Cm(H2O)n , for example sucrose has the molecular formula C12H22O11. The most important and prevalent carbohydrate is glucose, the primary metabolic fuel for the human body and indeed most forms of life on Earth. For more on ATP production and the Krebs cycle, see How Does Sugar Fit into a Healthy Diet?

Chemically, carbohydrates are classified based on the number of saccharides they contain: monosaccharides are made up of a single sugar molecule (examples are glucose and fructose), disaccharides contain two sugar molecules (examples are sucrose and lactose), oligosaccharides are medium-length chains of three to ten sugar molecules, and polysaccharides are long chains of sugar molecules that can be hundreds long (think of polysaccharides of long chains of monosaccharide units therefore they can be broken down in our digestive system into simple sugar molecules). From a dietary perspective however, it’s more relevant to classify carbohydrates based on how they’re digested and absorbed:

- Sugars, also called simple carbohydrates or simple sugars, include monosaccharides like glucose, fructose and galactose, and disaccharides like sucrose (one fructose and one glucose), lactose (one glucose and one galactose) and maltose (two glucoses). Sugars give food a sweet taste and are naturally found in fruit, dairy products and natural sweeteners like honey. They are digested and absorbed quickly and the glucose they contain has a rapid impact on blood sugar levels and insulin secretion. (Note that the presence of fiber in whole fruit helps to slow down the digestion of the sugars in fruit, see Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates).

- Starches are complex carbohydrates, polysaccharides composed predominantly of glucose. Starch is produced by most plants as an energy storage molecule and is commonly found in grains, legumes, and root vegetables such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, and cassava. Starch takes longer to break down during digestion and has a more gradual impact on blood sugar levels. See also What is a Safe Starch? and Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome.

- Fibers are also complex carbohydrates, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides that don’t get fully broken down by our digestive enzymes and instead are fermented by the bacteria and other microorganisms that live in our digestive tracts, see also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?. Fiber is discussed in detail starting in The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?, The Fiber Manifesto-Part 2 of 5: The Many Types of Fiber, The Fiber Manifesto-Part 3 of 5: Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber, and 5 Reasons to Eat More Fiber.

Whole-food carbohydrates, like fruits and vegetables, contain a mix of simple and complex carbohydrates, including fiber which slows own digestion and blunts the blood sugar response. Blood sugar regulation is further improved by ingesting fruits and vegetables as part of a complete meal that also includes protein and fats.

Refined carbohydrates refer to carbohydrates that have been processed. For example, when the bran and germ are milled away from whole grains to make refined grain products, most of the fiber is removed. The resultant starches are digested and absorbed rapidly, sometimes raising blood glucose levels as quickly as simple sugars. Examples are white flour made from whole wheat, white rice made from brown rice, table sugar made from whole sugar cane or sugar beets. Of course, whole grain foods are omitted on a Paleo diet due to being relatively empty calories and containing compounds that negatively impact gut health (both gut barrier and microbiome) and stimulate the immune system (causing inflammation). For more, see What Is The Paleo Diet?, How Gluten (and other Prolamins) Damage the Gut Gluten-Free Diets Can Be Healthy for Kids, Worse than Gluten: The Agglutinin Class of Lectins, Gluten Cross-Reactivity: How your body can still think you’re eating gluten even after giving it up., Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?), Why Grains Are Bad-Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, What Is A Leaky Gut? (And How Can It Cause So Many Health Issues?), How Do Grains, Legumes and Dairy Cause a Leaky Gut? Part 2: Saponins and Protease Inhibitors, and Are Pseudograins Pseudobad?.

Simple sugars can also be refined. A prominent example of a processed sugar is high fructose corn syrup. In this case, corn syrup is treated with enzymes to turn a proportion of the syrup’s glucose into fructose. High fructose corn syrup is discussed further in Why is High Fructose Corn Syrup Bad For Us? , Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems? and Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm?.

When we consume carbohydrates, they are broken down into simple sugars (mostly glucose) by our digestive enzymes and absorbed into our blood stream. This causes a rise in blood glucose levels, which stimulates the release of insulin and it’s this system (and what happens when things go wrong) that is what all the hubbub is about.

Carbohydrates Stimulate Insulin Release

When we consume carbohydrates, our digestive system first breaks complex carbohydrates down into monosaccharides (mainly glucose molecules), which are absorbed into our blood stream, causing a resulting rise in our blood sugar levels, (aka blood glucose levels). In response to that rise in blood sugar, the pancreas releases the hormone insulin, which facilitates the transport of glucose into the cells of the body and signals to the liver to convert glucose into glycogen for short-term energy storage in liver and muscle tissues and into triglycerides for long-term energy storage in adipose tissues. Once inside our cells, glucose in an energy source, being rapidly converted into ATP, the energy currency for all cells, via the Kreb’s cycle (a process that also uses oxygen and produces carbon dioxide, also called the Citric Acid Cycle or Cellular Respiration, explained in How Does Sugar Fit into a Healthy Diet?).

It’s a beautifully efficient system… until things go wrong. Chronically elevated blood sugar levels stimulate adaptations within cells, rendering them less sensitive to insulin. These adaptations may include decreasing the number of insulin receptors embedded within cell membranes and suppressing the signaling within cells that occurs after insulin binds to its receptor. This causes the pancreas to secrete even more insulin to lower the elevated blood glucose levels. This is called insulin resistance or loss of insulin sensitivity, when more insulin than normal is required to deal with blood glucose. When normal blood sugar levels can no longer be maintained, you get type 2 diabetes. See The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin , The Hormones of Hunger, How Does Sugar Fit into a Healthy Diet? and The Paleo Diet for Diabetes

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Insulin resistance is bad. It promotes weight gain and increases risk not only of obesity and diabetes, but also cardiovascular disease, many forms of cancer, asthma, allergies, PCOS, chronic kidney disease, many autoimmune diseases…. the list goes on.

So, if chronically elevated blood sugar levels makes you insulin resistant leading to health problems, then the key must be to not eat all those carbs, right? This thinking is what led to the now-debunked carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity and a surge in popularity of low-carb diets since the early 1990s. See New Scientific Study: Calories Matter

Low-carb diets do promote weight loss (and achieving a healthy weight reduces risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.). This fact has led to their increased popularity and the push towards ever lower carbohydrate intake, including the current ketogenic diet fad. However, rigorous and well-controlled metabolic ward studies have confirmed that low-carb and ketogenic diets don’t turn us into “fat-burning machines” with increased energy expenditure and preferential fat mass loss (see New Scientific Study: Calories Matter, Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised and How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut). These diets help us lose weight simply by creating a dietary structure that focuses on more satiating foods so that most individuals naturally achieve a caloric deficit (the Paleo diet which embraces whole foods sources of carbohydrates also results in weight loss by focusing on more filling foods, while also supporting high veggie intake and nutrient sufficiency, see The Importance of Vegetables, The Importance of Nutrient Density, and Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies). While weight loss is certainly more complicated than calories in versus calories out, a caloric deficit is still a necessary prerequisite for weight loss. See Paleo for Weight Loss and Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet

Low-carb diets do promote weight loss (and achieving a healthy weight reduces risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.). This fact has led to their increased popularity and the push towards ever lower carbohydrate intake, including the current ketogenic diet fad. However, rigorous and well-controlled metabolic ward studies have confirmed that low-carb and ketogenic diets don’t turn us into “fat-burning machines” with increased energy expenditure and preferential fat mass loss (see New Scientific Study: Calories Matter, Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised and How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut). These diets help us lose weight simply by creating a dietary structure that focuses on more satiating foods so that most individuals naturally achieve a caloric deficit (the Paleo diet which embraces whole foods sources of carbohydrates also results in weight loss by focusing on more filling foods, while also supporting high veggie intake and nutrient sufficiency, see The Importance of Vegetables, The Importance of Nutrient Density, and Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies). While weight loss is certainly more complicated than calories in versus calories out, a caloric deficit is still a necessary prerequisite for weight loss. See Paleo for Weight Loss and Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet

The fact is that insulin plays a lot of important roles in human health independent of its role in energy balance. So, while insulin resistance is clearly damaging, not eating enough carbs to secrete much insulin can also cause health challenges. This is very important to understand because it means that eating too-low-carb can cause the same kind of health problems as having insulin resistance, and indeed this is borne out in the research and discussed in detail in this very important post: The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body. Tldr; a moderate-carb approach is optimal to support the vast array of biological systems relying on insulin as a signaling molecule.

It’s also true that insulin sensitivity (meaning that the body is sensitive to insulin signaling and blood sugar levels are well managed) is not simply determined by the amount and types of carbs we consume. Insulin resistance is caused by lack of physical activity (prolonged sedentary periods), inadequate sleep and high stress, and in fact, insulin sensitivity may be more reflective of lifestyle than diet, see 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food.

Determining Optimal Carbohydrate Intake

Macronutrients are the nutrients we need in big (“macro”) quantities: fat, protein, and carbohydrate (in contrast to micronutrients like vitamins and minerals that are even more vital for health, but which we need in smaller quantities). Defining an optimal dietary macronutrient ratio—what percentage of our calories should come from carbs versus fat versus protein—is a contentious issue in the nutrition world, and the debate often bleeds over into the Paleo community as well. In fact, there’s a tendency for the media to misportray Paleo as being a low- or zero-carbohydrate diet, a high-fat diet, and/or a high-protein diet. In reality, the Paleo diet is a micronutrients first approach to nutrition with overall relatively balanced macronutrient ratios and lots of wiggle room to self-experiment. But, where do we start?

There’s a few different ways to come as this question:

- looking at the carbohydrate intake of hunter-gatherers,

- calculating the minimum carbohydrate requirement for sufficiency of nutrients that we primary obtain from vegetables and fruit,

- looking at how carbohydrate intake impacts the gut microbiome, and

- looking at intake levels that are correlated with higher disease risk.

No matter how you slice it, the conclusion is the same: moderate carbohydrate consumption (of whole food sources of carbohydrates like root vegetables and fruit) is superior to either low-carb or high-carb approaches.

What constitutes moderate carbohydrate consumption? I’m so glad you asked…

Hunter-Gatherer Carb Intakes

As we dive into understanding how many carbohydrates we should be eating as part of an optimal human diet, let’s start with hunter-gatherers. While the Paleo diet is far from historical re-enactment, we can still glean clues for an optimal human diet based on these societies virtually free from the chronic diseases that plague Western countries.

As we dive into understanding how many carbohydrates we should be eating as part of an optimal human diet, let’s start with hunter-gatherers. While the Paleo diet is far from historical re-enactment, we can still glean clues for an optimal human diet based on these societies virtually free from the chronic diseases that plague Western countries.

According to Loren Cordain’s 2000 publication, “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets” (which analyzed ethnographic data for 229 hunter-gatherer societies), the majority of hunter-gatherer populations ate between 22 and 40% of their diets as carbohydrates. That translates to 110 to 200 grams of carbohydrates per day on a 2000-calorie diet. There were a handful of societies falling outside that range, such as the lower-carb Inuit (3% calories as carbs, although they do have some potential additional sources not counted in this estimate like glycogen stores in whale blubber) and some groups eating as high as 50% carbohydrates, but those were by far the exception rather than the rule. In general, hunter-gatherers living close to the equator had higher carbohydrate (and total plant food) intakes than populations living closer to polar regions, and virtually every group residing between 11 and 40 degrees north or south of the equator (equivalent to the range between the northern part of Colombia and New York City) ate between 30 to 35% carbohydrates as a percent of total calories. On a 2000-calorie diet, that comes out to 150 to 175 grams per day. (See “Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers” for more on macronutrient ratios in hunter-gatherer societies. See also The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 2: Physiological & Biological Evidence, and The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?)

Some critics of the data (such as Katharine Milton) have pointed out that these carb levels could also be underestimated, due to a tendency for ethnographers to interact more with male hunters than female gatherers and consequently under-document the contribution of gathered plant foods. But, we can say with confidence that most hunter-gatherer groups eat about a third of their diet as carbohydrates, give or take!

Carbohydrate Quantity vs. Quality

Our modern diets differ from hunter-gatherer diets in more than just macronutrient composition. One of the biggest changes to Western diets (including the Standard American Diet) over the last 50 years is the replacement of whole foods sources of carbohydrates with refined carbohydrates.

When you compare average carbohydrate consumption in the United States now to 100 years ago (when chronic disease rates were only a fraction of what they are now), it’s not that different, averaging about 500 grams per day. What is different is the percentage of those carbohydrates that come from fiber, an indicator of how refined these carbohydrate sources are: the more refined a food is, the more carbohydrate grams per fiber grams it typically has. A century ago, Americans averaged about 30 grams of fiber daily (around USDA guidelines for fiber intake, and probably sufficient to support a healthy gut microbiome) whereas current dietary fiber intake averages about 15 grams (far below our recommended daily allowance). And, right when the percentage of carbohydrate coming from fiber starts to dip is right when we start seeing exponential increases in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity. See How Does Sugar Fit into a Healthy Diet? and 5 Nutrients You’re Deficient In…If You Eat Too Much Sugar

When foods are refined, it’s not just the fiber that’s stripped out. Vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals are also lost in the refinement process, and nutrient deficiencies themselves increase risk of disease. Combined with a large body of scientific evidence showing that low-carb high-fat diets do not provide a metabolic advantage, and in fact, low-fat high-carb diets perform equally as well from a weight loss standpoint (see Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet and New Scientific Study: Calories Matter), we’re seeing a picture where quality of carbohydrate, meaning that we’re getting them from whole-food sources like root vegetables and fruit, if far more important than total intake.

This more recent historical perspective indicates that carbohydrate consumption even at levels as high as 500 grams daily may be healthy when those carbohydrates come from high-quality sources, i.e., nutrient-dense fiber-rich whole foods.

Glycemic Load vs. Glycemic Index

One measure of a food’s carbohydrate quality is its glycemic load. It’s important to differentiate between a food’s glycemic index and its glycemic load. Glycemic index is a measure of how quickly the carbohydrates from a specific food impact blood sugar levels (the higher the glycemic index, the higher and faster blood sugar will rise after that food is eaten), but this concept doesn’t take into account that food’s carbohydrate density. Glycemic load measures how quickly the carbohydrates from a specific food impact blood sugar levels, adjusting for how many carbohydrates are likely to be consumed in a serving. Some foods have a high glycemic index but a low glycemic load: while the sugars in those foods are easily absorbed and cause a rapid impact on blood sugar, there aren’t that many of them, so these foods are often still healthy choices (watermelon is a good example; see the table below). Generally, a low glycemic load carb-containing food means that it’s a healthy slow-burning carbohydrate choice.

Eating Carbohydrates to Get Enough Fiber

Another way to frame the carbohydrate issue is to look at the bare minimum intake we’d need to get adequate daily fiber. (For a way more detailed rundown on why fiber is awesome, and why we need plenty of it in our diet, check out The Fiber Manifesto Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5, as well as Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses.) In short, fiber (especially antioxidant rich vegetable and fruit fiber) is critical for supporting gut health, promoting normal bowel movements, creating a healthy and diverse gut microbiome, protecting against many gut pathologies, regulating blood sugar, reducing inflammation, reducing the risk of certain cancers, and potentially even reducing the risk of heart disease and diabetes. It’s definitely not a nutrient we want to skimp on!

Another way to frame the carbohydrate issue is to look at the bare minimum intake we’d need to get adequate daily fiber. (For a way more detailed rundown on why fiber is awesome, and why we need plenty of it in our diet, check out The Fiber Manifesto Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5, as well as Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses.) In short, fiber (especially antioxidant rich vegetable and fruit fiber) is critical for supporting gut health, promoting normal bowel movements, creating a healthy and diverse gut microbiome, protecting against many gut pathologies, regulating blood sugar, reducing inflammation, reducing the risk of certain cancers, and potentially even reducing the risk of heart disease and diabetes. It’s definitely not a nutrient we want to skimp on!

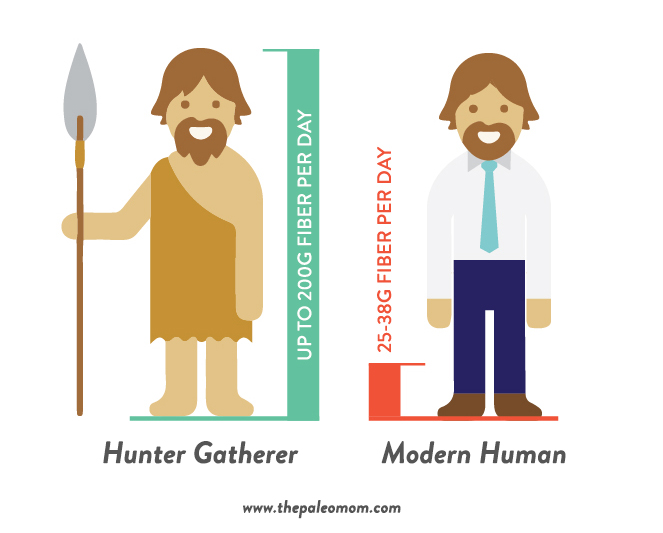

Current mainstream fiber recommendations are 25 grams per day for women and 30 to 38 grams per day for men. This is definitely less than what most Paleolithic and modern hunter-gatherers consumed. Boyd Eaton and Melvin Konner estimate 45.7 grams per day for a typical hunter-gatherer diet of 65% plant foods, comparable to the 35% carbohydrates mentioned earlier. Dr. Jeff Leach estimates that some hunter-gatherers eat as much as 200 grams of fiber per day! But, we’ll use the USDA guidelines for the sake of illustration.

Simple math shows that in order to meet current USDA fiber recommendations (25 to 38 grams per day), we need to eat a bare minimum of 50 to 76 grams of total carbohydrate. If we look at non-starchy vegetables with the highest ratio of fiber to non-fiber carbohydrates, we see that spinach comes out near the top, with roughly half of its carbohydrates coming from fiber. In order to get 25 grams of fiber per day from spinach, our minimum carbohydrate intake would be 50 grams. And for the record, using spinach, we’d need to eat about 45 cups of it (almost 3 pounds) to reach that level. That’s pretty ambitious, even for those of us who love veggies!

Using this logic, carbohydrate intakes of less than 50 grams per day are almost guaranteed to shortchange us on fiber. And that’s assuming we eat nothing but the highest-fiber carbohydrate sources out there! But hold that thought, because studies also show that the gut microbiome suffers when the only sources of dietary fiber are low-carb veggies like leafy greens.

Starch and the Microbiome, Another Reason to Up Carbs

Root vegetables, tubers, and fruit are higher carbohydrate whole food choices, but also contain unique types of fiber (like pectin in fruit and resistant starch in roots and tubers) that are incredibly important for the gut microbiome. For example, abundance of the incredibly important Methanobrevibacter is positively associated with higher carbohydrate consumption (both recent and long-term). Bifidobacterium thrive on RS2 and RS4 resistant starch. Roseburia love pectin. A closer look at how the gut microbiome responds to lack of these foods reveals that even a fiber-sufficient low-carb diet is likely inadequate to support health.

Root vegetables, tubers, and fruit are higher carbohydrate whole food choices, but also contain unique types of fiber (like pectin in fruit and resistant starch in roots and tubers) that are incredibly important for the gut microbiome. For example, abundance of the incredibly important Methanobrevibacter is positively associated with higher carbohydrate consumption (both recent and long-term). Bifidobacterium thrive on RS2 and RS4 resistant starch. Roseburia love pectin. A closer look at how the gut microbiome responds to lack of these foods reveals that even a fiber-sufficient low-carb diet is likely inadequate to support health.

A 2019 study of people following the Paleo diet showed alarming levels of TMAO (which is linked to increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease), attributable to a shift in the gut microbiome (this study is discussed in detail in Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, but also see Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses and The Link Between Meat and Cancer). Importantly, the study participants were consuming adequate dietary fiber, 27.4 grams daily from an average of 6.7 servings of vegetables per day! However, they also averaged only 99 grams of carbohydrate daily (compared to 202 grams daily in the controls), which tells us that most of the vegetables they consumed were lower-carb, non-starchy options. In fact, while the control group averaged 4.5 – 14.2 grams of resistant starch per day, the Paleo group averaged only 2.6 – 6.1 grams per day. The consequence of this low-starch intake was serum TMAO measured at a whopping 9.53 µM, compared to the control group’s 3.93 µM. This increase in TMAO was likely due to changes in the gut microbiome, most notably a decrease in probiotic Bifidobacterium and Roseburia species (which love the fiber in root veggies and fruit), and concurrent increase in undesirable Hungatella species.

This makes a strong case for 100 grams of carbohydrate still not being adequate to support the gut microbiome because, even with adequate total fiber intake, it doesn’t allow enough room for root vegetables and fruit in the diet. An exact minimum is hard to pinpoint with this study, but something closer to the hunter-gatherer 150 grams daily is a good starting point.

Root vegetables and fruit have a lower ratio of fiber to non-fiber carbs, but are also denser fiber sources (see Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome and Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates). So, you’d only need about 3.5 cups of baked sweet potato to get your 25 grams of fiber (compared to that 40 cups of spinach!), which also puts you closer to hunter-gatherer carb intakes of about 150 grams of total carbs. Of course, if we’re keen to emulate hunter-gatherer fiber intake with the modern food supply, it would be incredibly challenging to do so without total carbohydrate intake creeping up towards 300 grams or more. But, even looking beyond the gut microbiome, 300 grams of carbs daily doesn’t necessarily look like a bad thing (provided those carbs are coming from nutrient-dense whole vegetables and fruit!). Let’s look at the other evidence.

The AMDR and Balanced Macros

Another consideration with optimizing carbohydrate intake is ensuring we avoid the effects of eating too much or too little of each macronutrient (not just carbohydrates, but also fat and protein). On one hand, an extremely high carbohydrate intake (more than 70% of calories) leaves less room for fat and protein in our diet, which creates its own set of problems. Inadequate fat can decrease our absorption of vitamins A, D, E, and K (which ultimately affect every system in our bodies), as well as deprive us of essential fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6). Inadequate protein can reduce the preservation of lean muscle tissue, reduce our immune function, negatively affect our bone mineral density, and cause a host of other problems related to insufficient intakes of essential amino acids. See The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?

On the other hand, too little carbohydrate (with lots of protein and fat) could mean an insufficiency of not only fiber, but also of certain nutrients and phytochemicals found most abundantly in carbohydrate-rich foods, even when choosing quality options (including vitamin C, polyphenols, chlorophyll, carotenoids, isothiocyanates, and organosulfur compounds, all of which play various roles in disease prevention). (See The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals, Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?, and Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?) The solution? We can balance our macronutrients by eating moderate amounts of carbohydrate, fat, and protein, rather than excessive or extremely limited levels of any single one. Returning to hunter-gatherers for a minute, Cordain’s analysis found that most populations consumed between 19 and 35% protein and 28 and 58% fat. Eating about a third of our diet as carbohydrates (about a third as protein and about a third as fat) fits in nicely with the patterns we’ve observed among healthy hunter-gatherers, and seems to be the sweet spot for optimizing vitamin, mineral, phytonutrient, fiber, essential amino acid, and essential fatty acid intake!

Additional science supports the idea that balanced macronutrients are more sustainable and health-supportive than macronutrient extremes (such as very low fat or very low carbohydrate). Another way to frame the issue is to determine how much of each macronutrient we need to avoid problems associated with either micronutrient deficiency or excess.

Additional science supports the idea that balanced macronutrients are more sustainable and health-supportive than macronutrient extremes (such as very low fat or very low carbohydrate). Another way to frame the issue is to determine how much of each macronutrient we need to avoid problems associated with either micronutrient deficiency or excess.

The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine has set Accepted Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR) for protein, fat, and carbohydrates based on evidence from interventional trials with support of epidemiological evidence that suggests a role in the prevention or increased risk of chronic diseases and based on ensuring sufficient intake of essential nutrients. While these dietary guidelines don’t match up perfectly with hunter-gatherers, we see some alignment with AMDR for fat estimated to be 20 to 35 percent of total energy and protein estimated to be 10 to 35 percent of total energy for adults. And while the AMDR for carbohydrates as an estimated 45 to 65 percent of total energy (and below 25 percent from sugars) doesn’t quite align with hunter-gatherer intakes, it does support the tenet that consuming too little carbohydrate can shortchange us terms of fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals.

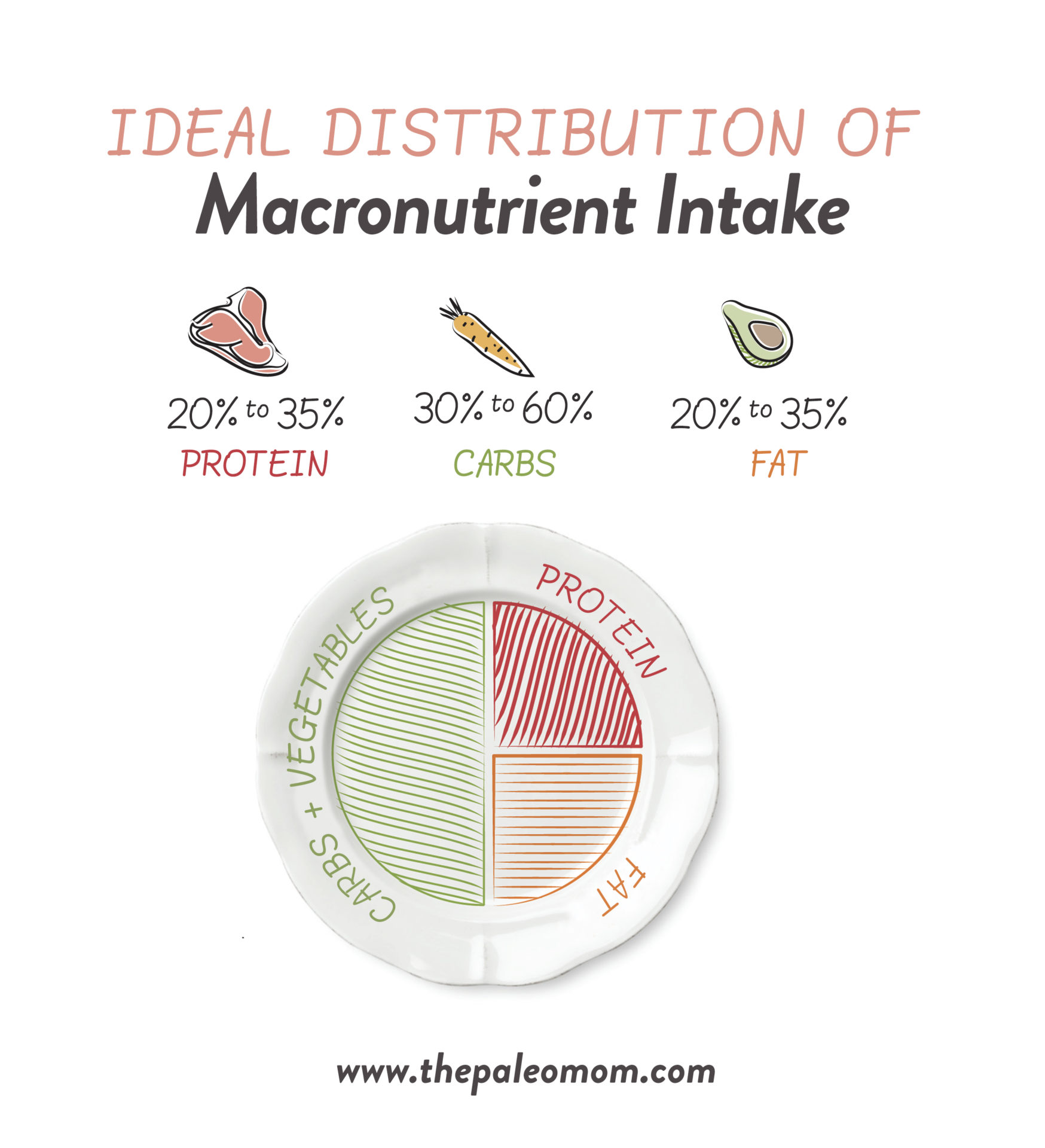

When taken together with hunter-gatherer intake, you end up with the following ideal distribution of macronutrient intake:

- ~20 to 35% calories from fat

- ~20 to 35% calories from protein

- ~30 to 60% calories from carbohydrate

But, What About Low-Carb and Ketogenic Diets?

Extremely low-carb ketogenic diets have gained quite a bit of popularity lately. This type of diet has long been used to manage epilepsy (and to a lesser extent, other neurological pathologies, though the research is more limited), and there’s some evidence that ketogenic diets could improve the outcome of certain cancers (although, importantly, not as a treatment for cancer categorically: some tumors become more aggressive when starved of glucose!). It’s definitely true that restricting carbohydrate intake to very low levels could have therapeutic benefits in some situations.

For most of us, though, extremely low-carb diets are neither necessary nor beneficial. Previously, I’ve written about the documented adverse effects of ketosis (see “Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised”). Along with reported gastrointestinal disturbances, impaired mood, hypoglycemia, kidney stones, increased susceptibility to infection, long QT intervals, hair loss, muscle cramps or weakness, impaired concentration, disordered mineral metabolism, increased fracture risk, and a shift towards atherogenic lipid profiles in some people, some potential issues require much more research than we currently have available before we fully understand the long-term effects of ketogenic diets. Also, as you would expect, ketogenic diets have been shown to have a very negative impact on the gut microbiome, discussed in detail in How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut.

In addition, when we consider the essential roles of insulin in the human body that are not related to the metabolism of glucose, it quickly becomes apparent that, while insulin resistance is clearly bad, avoiding dietary carbohydrate intake’s can result in similar health detriment. Again, this is discussed in detail in The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body

8+ Veggies & 3+ Fruit Daily

Studies unequivocally show that eating a diet rich in fresh vegetables and fruit is the single most important dietary factor for reducing disease risk, see The Importance of Vegetables, Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates and The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!.

Studies unequivocally show that eating a diet rich in fresh vegetables and fruit is the single most important dietary factor for reducing disease risk, see The Importance of Vegetables, Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates and The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!.

The most current research shows that eating 8 or more servings of whole vegetables and fruits daily in the minimum amount to maximize the benefits of these fiber-rich, vitamin-rich, mineral-rich and antioxidant phytochemical-rich foods. However, fruit have also been shown to be independently beneficial, with research showing 3 or more servings of fruit daily maximizes benefits (see Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates). With fruit, it’s important to be cognozant of total fructose intake and stay below 40 grams daily. Depending on the fruit, that sets a limit to 5 to 8 servings of fruit daily.

Also, there’s research showing a serving of mushrooms per day is great for the gut microbiome (see Elevating Mushrooms to Food Group Status) and research showing that a serving of nuts and seeds per day is associated with diverse health benefits (see Nuts and the Paleo Diet: Moderation is Key).

Taken together, a strong argument can be made for DAILY consumption of:

- 8+ servings of vegetables, including from each of cruciferous veggies, the parsley family, leafy greens, roots and tubers, the onion family, and other veggies

- 3+ servings of fruit, including from each of the apple family, berries and citrus most days, rounding out with melons, tropical and subtropical fruits (and limiting to <40 grams fructose daily)

- 1+ servings of mushrooms, choosing as much variety as possible

- 1 serving of nuts and seeds

I know that sounds like A LOT of plant foods. But, I want to emphasize that it’s quite reasonable (and easy to achieve with a #threequartersveggies approach to each meal), and a good way of making sure to get adequate amounts of a variety of fiber from nutrient-dense sources. A serving of vegetables, fruit or mushrooms is standardized at 80 grams raw. A serving of nuts and seeds is 28 grams.

Let’s look at how this translates to total carbohydrate and calorie intake, using common options.

| Fiber (g) | Carbs (g) | Calories | |

| Sweet potato | 2.4 | 16.1 | 69 |

| Acorn squash | 1.2 | 8.3 | 32 |

| Parsnip | 3.9 | 14.4 | 60 |

| Brussels sprouts | 3.0 | 7.2 | 34 |

| Kale | 1.4 | 6.6 | 34 |

| Romaine lettuce | 1.7 | 2.6 | 14 |

| Carrot | 2.2 | 7.7 | 33 |

| Leek | 1.4 | 11.4 | 49 |

| Mushrooms, white | 0.8 | 2.6 | 18 |

| Walnuts | 1.9 | 3.8 | 183 |

| Apple | 1.9 | 11.0 | 42 |

| Blueberries | 1.9 | 11.6 | 46 |

| Banana | 2.1 | 18.2 | 71 |

| TOTAL: | 25.8 | 121.5 | 685 |

You can see how slowly the carbohydrate grams and calories accumulate, so there really is no reason to be afraid of root vegetables and fruit!

This is also why so many athletes following a Paleo diet add white rice into their diet to increase carbohydrate intake. There really isn’t a good argument for limiting vegetable and fruit intake (even starchy veggies). These nutrient-dense low- to moderate- glycemic load foods are awesome options for everyone!

If Sugar is Bad, How About Sugar Substitutes?

We can certainly agree that refined carbohydrates are best avoided or at least strictly limited. But, let’s briefly talk about ingredients designed to cheat sweet. Low-carb products are filled with sugar substitutes, like high-fructose based sweeteners like agave, artificial sweeteners, sugar alcohols like sorbitol and even “natural” sweeteners like stevia and monk fruit extract. These are all covered in detail in:

- Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners,

- Is It Paleo? Fructose and Fructose-Based Sweeteners (I’m looking at you, Agave!),

- The Trouble with Stevia, and

- What’s the Next Superfood Sweetener?

Natural sugars, and how occasional consumption can fit into a healthy diet, are discussed in:

- How Does Sugar Fit into a Healthy Diet?

- Blackstrap Molasses: The Sugar You Can Love!

- Honey: The Sweet Truth About a Functional Food!

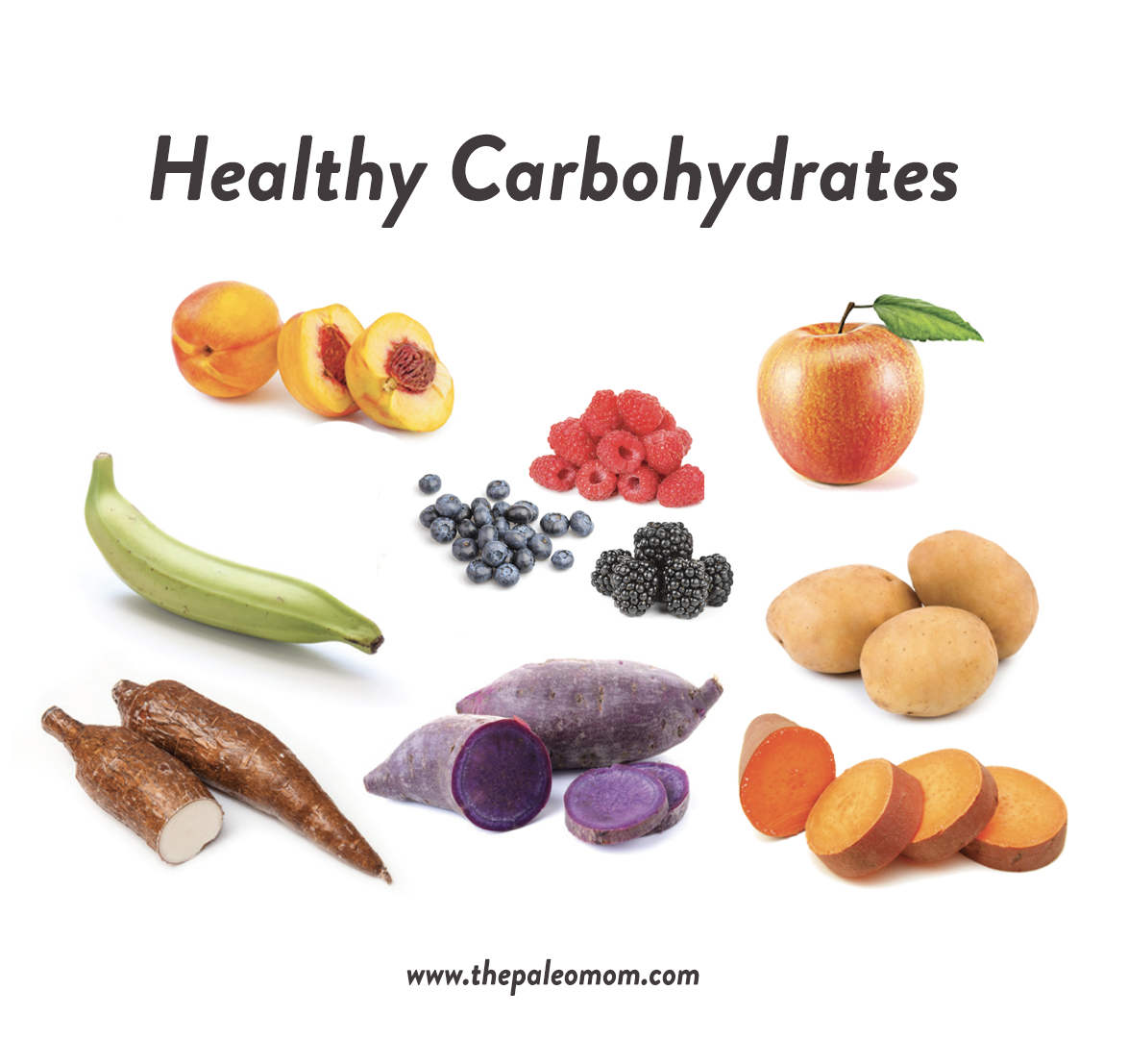

Healthy Paleo Carbs to Choose From

When whole fruits and vegetables are the major source of dietary carbohydrates, even the “carbiest” options tend to be packed with nutrients and fiber and have a low or moderate impact on blood sugar levels. The following are healthy carbohydrate-rich foods, packed with fiber, vitamins and minerals!

| Glycemic Index (glucose = 100) | Serving Size | Glycemic Load | Fiber | Nutrients (more than 10% of RDA in one serving) | |

| FRUITS | |||||

| Apple | 36 | 120 g (1 medium = 182 g) |

5 | 2.9 g | Vitamin C, polyphenols |

| Banana | 48 | 120 g (1 medium = 118 g) |

11 | 3.1 g | Vitamins B6 and C, potassium, manganese |

| Grapefruit | 25 | 120 g (½ fruit = 123 g) |

3 | 1.9 g | Vitamin C, carotenoids, betaine |

| Grapes | 59 | 120 g (1 cup = 151 g) |

11 | 1.1 g | Vitamins C and K |

| Kiwi | 53 | 120 g (1 medium = 76 g) |

6 | 3.6 g | Vitamins C, E, and K, potassium, copper |

| Orange | 45 | 120 g (1 medium = 130 g) |

5 | 2.8 g | Vitamins B9 and C, betaine |

| Mango | 51 | 120 g (1 cup cubes = 165 g) |

8 | 2.2 g | Vitamins B6 and C |

| Peach | 42 | 120 g (1 medium = 150 g) |

5 | 1.8 g | Vitamin C |

| Pear | 38 | 120 g (1 medium = 178 g) |

4 | 3.7 g | Vitamin C, chromium |

| Pineapple | 59 | 120 g (1 cup chunks = 165 g) |

4 | 1.7 g | Vitamin C, magnesium, bromelain |

| Watermelon | 72 | 120 g (1 cup cubes = 152 g) |

4 | 0.5 g | Vitamin C, carotenoids |

| STARCHY VEGETABLES | |||||

| Acorn squash* | 75 | 150 g (1 cup cubes = 205 g) |

6 | 5.3 g | Vitamins B1, B6, and C, magnesium, potassium, manganese, carotenoids |

| Beet | 64 | 80 g (1/2 cup sliced = 85 g) |

5 | 3.4 g | Vitamin B6, manganese, betaine |

| Butternut squash* | 72 | 150 g (1 cup cubes = 205 g) |

6 | 3.0 g | Vitamins B1, B3, B6, B9, C, and E, magnesium, potassium, manganese, carotenoids |

| Carrots | 39 | 80 g (1/2 cup sliced = 78 g) |

2 | 2.3 g | Vitamin K, carotenoids |

| Cassava, boiled | 46 | 100 g (1 cup cubed = 206 g) |

12 | 1.8 g | Vitamin C, manganese |

| Green plantain* | 40 | 120 g (1 cup sliced = 154 g) |

13 | 2.8 g | Vitamins B6 and C, magnesium, potassium, carotenoids |

| Parsnip | 52 | 80 g (1/2 cup sliced = 78 g) |

4 | 2.8 g | Vitamins B9 and C, manganese |

| Potato, baked | 85 | 150 g (1 small = 138 g) |

26 | 3.3 g | Vitamins B1, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, and E, magnesium, potassium, phosphorous, copper, manganese |

| Potato, boiled | 54 | 150 g (1/2 cup chopped = 78 g) |

15 | 3.0 g | Vitamins B1, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, and E, magnesium, potassium, phosphorous, copper, manganese |

| Sweet potato | 61 | 150 g (1 cup cubed = 200 g) |

17 | 3.8 g | Vitamins B6 and C, potassium, manganese, carotenoids |

| Taro | 55 | 150 g (1 cup sliced = 132 g) |

4 | 7.7 g | Vitamins B1, B6, C, and E, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, copper, manganese |

| Turnip | 62 | 150 g (1 cup chopped = 144 g) |

2 | 3.1 g | Vitamin C |

| Rutabaga (swede) | 72 | 150 g (1 cup cubed = 170 g) |

7 | 2.7 g | Vitamin C, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, manganese |

| Yam | 54 | 150 g (a cup cubed = 136 g) |

20 | 5.8 g | Vitamins B1, B6, and C, potassium, copper, manganese |

*plantain and winter squash are technically fruits, but they cook like vegetables which is why they are grouped with other veggies in this table

So, How Many Carbs Should We Eat?

So, what’s the take-home message as far as carbohydrate recommendations go? For most people, going below 100 grams of carbohydrate per day for extended periods isn’t a good idea (unless a ketogenic diet is being used therapeutically for a specific condition and while under close medical supervision). Assuming a 2000-calorie per day diet, a range of 150 to 300 grams (total carbohydrate from whole food sources) is where the preponderance of the evidence points to, no matter how we approach the derivation!

Citations

Cordain L, et al. “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92.

Eaton SB & Konner M. “Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications.” N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 31;312(5):283-9.

Gross LS, et al, Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: an ecologic assessment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 May;79(5):774-9.

Hylla S, et al. “Effects of resistant starch on the colon in healthy volunteers: possible implications for cancer prevention.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Jan;67(1):136-42.

Johnston KL, et al. “Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome.” Diabet Med. 2010;27:391-397.

Nilsson AC, et al. “Including indigestible carbohydrates in the evening meal of healthy subjects improves glucose tolerance, lowers inflammatory markers, and increases satiety after a subsequent standardized breakfast.” J Nutr. 2008;138:732-739.

Ströhle A & Hahn A. “Diets of modern hunter-gatherers vary substantially in their carbohydrate content depending on ecoenvironments: results from an ethnographic analysis.” Nutr Res. 2011 Jun;31(6):429-35.