“Everything causes cancer is not the conclusion you want to draw from science”

— John Oliver

Last week on social media, I shared an article that I had written on The Link Between Meat and Cancer, which details the mechanisms understood so far in the scientific literature and what that means in the context of a diet devoid of grains and rich in vegetables. The post garnered a good degree enthusiasm, but also one fascinating comment pointing me to an older mini-review paper that listed phytochemicals found in common foods like cabbage and coffee that have carcinogenic properties. The commenter summarized “If chewing tobacco causes cancer, it’s likely that chewing other vegetables also causes cancer.”

The vast body of scientific research into how a fruit and vegetable-rich diet affects cancer risk indicates that the more of them you eat, the lower your risk of developing cancer (see for example this review published just last month). But, that’s different than saying that every compound in every vegetable is health promoting. Just like my original article highlighted the fact that meat consumption may increase risk of cancer depending on the contents of a person’s entire diet. Context matters.

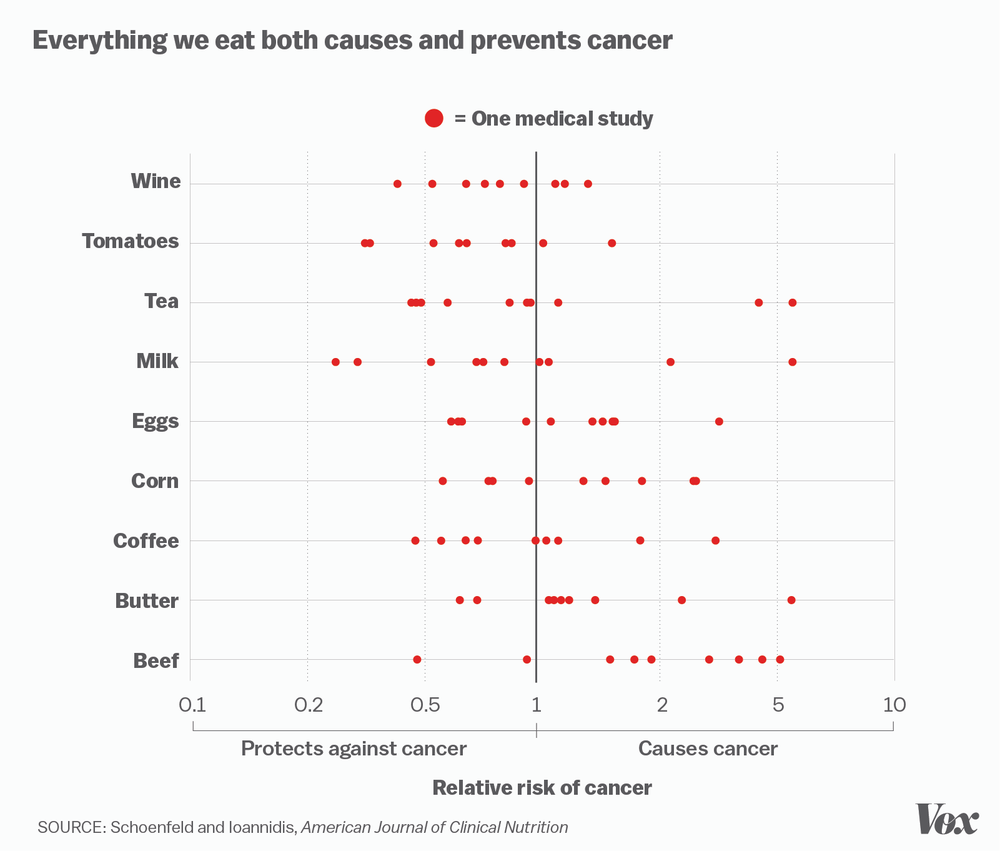

In fact, when viewed in isolation, there aren’t many clear-cut lines in terms of what foods cause and what foods prevent cancer:

Scientific exploration is about understanding our world, how things work, and how things interrelate. Sometimes technological advances cause a surge in scientific discovery, but generally, our understanding unfolds slowly with incremental iterations until scientific consensus is reached.

[ Aside: When scientific consensus is reached, an idea moves from hypothesis to theory. Those two words are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. You might say “I have a theory about that!” when you really mean that you have a hypothetical explanation. However, in science, the word theory means accepted scientific fact, the explanation for why something happens, the cumulative understanding gleaned from the body of scientific literature on a topic, as in The Theory of Gravity. Notably, there is currently no Theory of Optimal Human Nutrition. Scientists are still investigating the many facets of this topic, incrementally adding to our knowledge. In the meantime, we can make some nutrition statements with a great deal of confidence (like being deficient in even one vital nutrient is bad) and others are still open for debate (like The Great Dairy Debate). ]

Until all the data is in, results can seem confusing or conflicting, like how murky the waters are in terms of diet links to cancer. But, this isn’t a failure of science. This is just how science works. It’s slow. It’s iterative. Big questions have to be divided into teeny tiny pieces that are each investigated with a study or a series of studies. The human body is fantastically complex, and the only way to understand it is to design studies to answer one very specific and detailed question at a time. The insight gleaned from tens of thousand of studies can then be combined to form a bigger picture, a complete understanding. Each little detail will eventually fit into place (or a flaw in a study will be identified).

What is a problem though, is that the way that science is being reported on. I too often see headlines and articles or television segments completely misrepresenting the results of a study (like last Fall’s media frenzy about hunter-gatherer sleep or the reporting that spurred me to write Rebuttal to “Paleo Diet Could Lead To Rapid Weight Gain, New Study Shows”), or failing to provide the study context, or failing to interpret the study results in an actionable and meaningful way. Newly published scientific studies become sensationalist headlines and manage to lose their substance along the way. And, all of this hype is feeding skepticism, apathy, and anti-science sentiments in the public.

“Too often, a small study with nuanced tentative findings gets blown out of all proportion when it’s presented to us, the lay public.” — John Oliver

That’s why I enjoyed John Oliver’s segment on Scientific Studies on last week’s Last Week Tonight so much. He touched on some serious issues relating not just to science funding, but also to science reporting that I believe are essential to address in our society. I’d like to add my voice to this conversation.

Here is the clip from the show. The profane language is bleeped, but there still may be some inappropriate phrases for little ears to hear. I would give this a PG rating for sure:

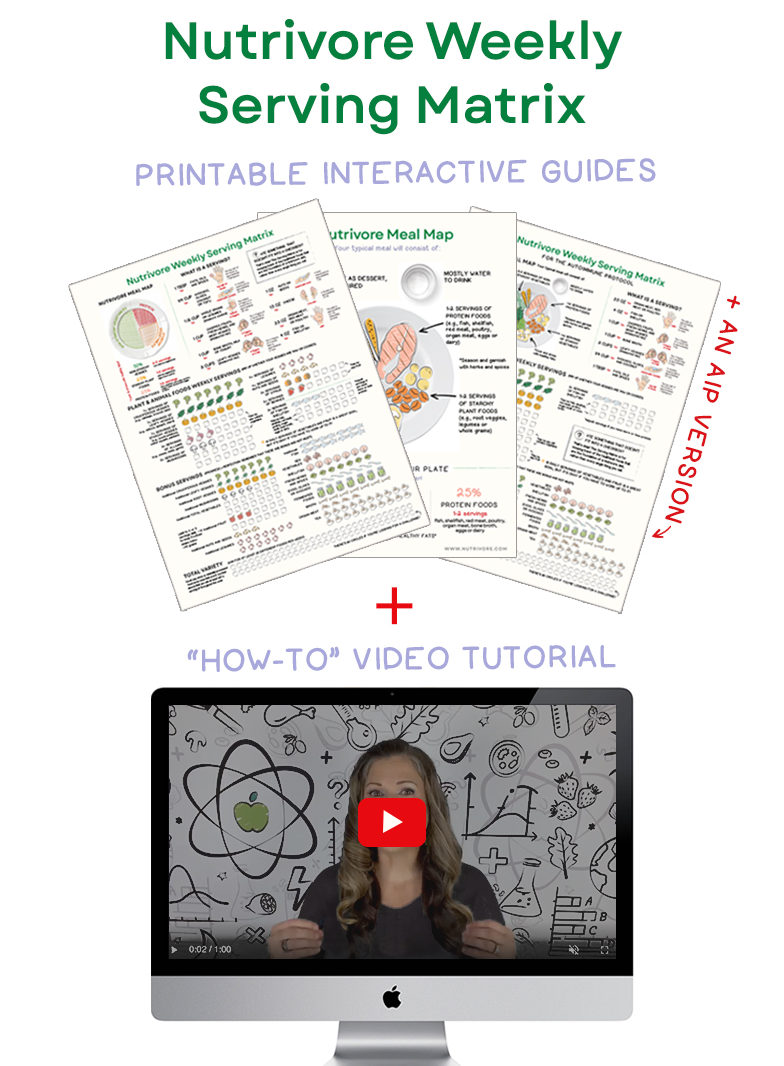

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

“Science is, by its nature, imperfect. But, it is hugely important and it deserves better than to be be twisted out of proportion and turned into morning show gossip.” –John Oliver

Thank you, Mr. Oliver. I agree! The soundbite-ification of scientific studies to fit within a ratings-geared talk show, magazine, or website narrative does us all a disservice. But, that doesn’t meant that sharing scientific advances with the public should be avoided! Actually, it means that science reporting needs to be a bigger focus with much more time dedicated to it (written and air time) in order to get into details, provide background and context, and explain how this study fits into the larger body of scientific knowledge in the field thus far. Those reporting on science need to read the paper and not just the press release; they need to understand what they are reading to be able to report on it accurately. And, we need to change the reward system for researchers, journals and educational institutions: a detailed conversation needs to be more important than a headline.

“Scientists themselves know not to attach too much significance to individual studies until they are placed in the much larger context of all the work taking place in that field.” –John Oliver

It absolutely is possible to explain detailed scientific concepts efficiently, in a way that is engaging and entertaining, and that respects the general public’s ability to engage in and understand science. This website and my New York Times bestselling first book The Paleo Approach are proof positive of that!

You probably already know that I have a medical research background. I earned my PhD in medical biophysics at the age of 26 and did four years of research at the postdoctoral level before the birth of my first daughter combined with my health struggles compelled me to take time off. The break in my career, originally intended to be temporary, enabled and propelled my health journey (which included losing 120 pounds and mitigating a dozen diagnosed health conditions) and led to the launch of ThePaleoMom (read more about my background in About Sarah Ballantyne, PhD).

Because of my education and longstanding passion for improving scientific literacy, I take a science-based approach to everything that I do. I feel that it’s essential to explain the scientific foundation for every recommendation. This means taking the time to explain scientific concepts (why most of my articles are 5 or 6 times longer than blog industry standard) without oversimplification or “dumbing it down”. And, it means identifying where research is and is not conclusive, admitting where there is no consensus, including conflicting reports and how they impact interpretation, and outlining the limits of current scientific knowledge on the topic. In short, context.

This approach makes me unusual even in Paleo and alternative health circles, and I often feel that I’m waging battle against misinformation, dogma and hype (yes, even within these more informed communities). And, alarmingly, I’m seeing more and more anti-science sentiments.

And, no wonder people are losing their faith in science! But, it’s not just how science is being reported on, although Mr. Oliver’s segment made a strong case for this being a major contributor:

“And if you think I’m exaggerating about impact that this misreporting can have on our faith in science, look at an example from some of the people most guilty of it…. [clip] …In science, you don’t just get to cherrypick the parts that justify the parts you were going to do anyway, that’s religion!” –John Oliver

Another major contributor to anti-science sentiments is pseudoscience articles/resources/websites that use just enough real science to make the reader believe that the author has a valid point, sometimes even including links to scientific papers with complex titles that may or may not have anything to do with the article itself. Whether a simple misunderstanding of the science innocently made by an author who lacks sufficient background to accurately interpret or relay the information, or the more insidious deliberate preying on the reader’s fears veiled by technical sounding mumbo jumbo to sell a product or a brand, these articles can be tough for the layperson to identify. And, they erode the credibility of good science reporting either by the fact that once someone feels like they’ve been duped, they’re not eager to go there again, or because the individual has become so invested in the pseudoscience message that they aren’t in a frame of mind to reevaluate. Wherever on this spectrum, the result is skepticism and a tendency to dismiss scientific evidence.

“Is science bull$h!t? To which the answer is clearly no, but there is a lot of bull$h!t currently masquerading as science.”–John Oliver

Dismissing scientific studies (or cherrypicking) is a major problem, even among the Paleo and alternative health communities that pride themselves on their basis in science!

It’s a favorite phrase in the alternative health and Paleo communities: “correlation does not equal causation”. It’s certainly true! However this phrase is now being used to dismiss any scientific evidence that does not support an individual’s personal beliefs about diet, lifestyle, medication, treatments, biohacks, or whatever other hot topic du jour. And this means that really important information is erroneously ignored.

Many are just as quick to dismiss studies performed in animals as they are to dismiss epidemiological studies. Or dismiss a study linking meat consumption to cancer because it wasn’t performed using grass-fed beef (addressed in The Link Between Meat and Cancer). I’d like to urge everyone to tread carefully here. Yes, when it comes to all of these topics, the bigger picture is much more complex than an individual study can tell us. The human body is extremely complex, and it is true that we understand only a fraction of how all the systems in the body interact with each other, diet, lifestyle and the environment. But these studies still help increase our understanding of health and are our best tools to inform our choices.

“The truth is, while studies performed on rats and mice are undeniably useful, their applicability to humans can be limited. The overwhelming majority of treatments that work on lab mice do not wind up succeeding in humans.” –John Oliver

Ultimately, this is true. But, let me take a step backward. Scientific investigation starts with exploration studies (like epidemiological studies looking for correlations between A, perhaps some diet factor, and B, perhaps risk of a specific disease). This is what Mr. Oliver referred to as P-hacking. As one of my husband’s mentors told him nearly 20 years ago: “don’t plot something against something else and call it science”. That being said, measuring statistical significance is our best tool for identifying causality. A correlation is an indication that something interesting is happening, but it’s not proof. Instead, it’s the hypothesis, a vital first step to scientific investigation.

Once a potential link has been identified, mechanistic studies are performed to determine exactly how A and B relate to each other. Does A cause B? What are the molecular details of exactly how A does that? Is there an intermediary? What other factors affect how A causes B. What can interfere with that system? These questions are answered typically with mechanistic studies done in rats and mice (and cell culture systems, and yeast, and other animals like fish and frogs and even fruit flies), and because of the huge similarity in the biological processes of all animals, these studies have tremendous merit and advance our understanding of how A and B are linked.

From there, intervention studies evaluate whether a system can be manipulated to achieve a desired result. If B is a bad thing, and A causes it, can we add a drug or a supplement or an antibody to the system to block A from causing B? Drug development studies (pre-clinical through clinical trials) fall under this category. Finally, comes the Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial (RCCTs), the gold-standard to test an intervention, whether that be a new diet, a new drug, a vitamin supplement, or a lifestyle intervention. This is where translation from animals to humans can be limited, in interfering with a system by administering a compound (like a new drug), which is due to the small molecular differences in the biological systems between animals and humans.

Not all science has to end in intervention studies and RCCTs. In fact, the majority of scientific advancement (at least in biology) comes from mechanistic studies. Yes, some of those studies still need be interpreted with a grain of salt; but generally, the concern over limits to human application comes from intervention studies. Mechanistic studies on the other hand are powerful tools for advancing scientific knowledge.

The power of the Paleo diet and lifestyle is that its underpinnings are based in science. As such, the tenets of the Paleo diet are continuing to shift as more science is performed (like accepting that white potatoes and green beans are probably fine for most people). And while the number of mechanistic studies and randomized controlled clinical trials that inform Paleo guidelines continues to increase, the original science supporting our way of life was correlative and epidemiological studies. It’s important to recognize that the current incarnation of Paleo may not be perfect; and, I plan on adjusting my recommendations if compelling science is performed to suggest that the Paleo template could be better. When we dismiss scientific evidence, even when the studies are preliminary and especially when we selectively dismiss science that indicates something contrary to our tenets, we undermine our own validity.

“Just because a study is industry-funded or its sample size was small or it was done in mice, doesn’t mean it’s automatically flawed. But, it is something the media reporting on it should probably tell you about.” –John Oliver

A small rigorous study can have more statistical power than a huge less well-controlled study. Non-institutional funding does not doom a study to bias. Just because the results of a study don’t seem to make sense, or don’t fit perfectly with previous notions, does not mean it’s bad science. Instead of dismissing science, let’s have a conversation.

Our biggest issue is that scientific research is grossly underfunded. Not only are replication studies rarely funded, underappreciated, and hard to publish, but even funding for basic biological research (topics that aren’t directly applicable to biotech advancement or drug discovery) has been slashed dramatically over the last few decades. And, when a study is underfunded, rigor can be sacrificed. Career advancement for scientists is dependent on discovery and publication; and across all sciences, the less monetizable a line of research is (the more theoretical or purely basic understanding of systems, and the less patentable), the less likely it is to get funded and the harder it is for the researcher succeed in their career path.

And of course, all science needs to be reported faithfully by the media, with context, and with respect for the reader/viewer.

Cancer is certainly not caused by everything. And our day-to-day food and lifestyle choices do matter. That being said, the scientific research on the topic is far from complete enough to give us definitive guidelines. But, when looking at the body of scientific literature as a whole, we do see that nutrient-dense vegetable-rich anti-inflammatory diets combined with adequate sleep, stress management, low exposure to toxins, and an active lifestyle are all good choices to make to lower our risk as much as possible, given that other factors like genetics are beyond our control.

Thank you Mr. Oliver for highlighting this in such an entertaining and eye-opening way!

Science is a pretty amazing process; and, if you’ve read even a handful of my articles, you know that it’s something I am extremely passionate about. I’m not sure what the call-to-action is, except to encourage you to educate yourself, become a science nerd, go and read the original paper when you see a news story that peaks your interest, read everything with a healthy dose of skepticism but also be open to new information, think critically about information that contradicts what you think you know, demand respect from your news sources, ignore the hype, and engage in the more detailed conversation that proves that you care about the context.

TPV Podcast, Episode 195, The Latest in Weight Loss Research

TPV Podcast, Episode 195, The Latest in Weight Loss Research