How much sleep do you need to wake up feeling refreshed in the morning, up and at’em without the need for coffee to shake the drowsies off. While modern biological research provides us with a likely average requirement (see Sleep Requirements and Debt: How do you know how much sleep you need?), what insight can we glean from hunter-gatherers and evolutionary biology?

In the past year, several studies have looked at the sleep patterns of hunter-gatherer societies (with the implication that their habits offer clues for what’s best for us in the modern world!). The most highly publicized one (published in Current Biology) examined the sleep patterns of pre-industrialized societies in Tanzania, Namibia, and Bolivia. And, if we trust the huge number of media headlines that followed, the research seemed to show that healthy hunter-gatherers only get about 5.7-7.1 hours of sleep per night. That’s much less than what’s commonly advised for optimal health (The National Sleep Foundation recommends 7-9 hours per night for adults, see Sleep Requirements and Debt: How do you know how much sleep you need?), and closer to what someone might get while staying up too late checking Facebook and waking up early in the morning with the help of an alarm clock and coffee! Even Science Daily, usually more balanced than mainstream media, came out with the headline, “Sorry, pre-modern people don’t get more Zzzzs than we do.” What’s going on here?!

Actually, this study is a great example of the media (and even reputable science outlets!) misinterpreting some important research (see Everything Causes Cancer: How much can science really tell us?). Sleep is such a critical component of health, it’s dangerous to validate our society’s late bedtimes and caffeine obsession with something that sounds scientific. So, let’s look past the misleading way this study was reported and see what it really found.

The Study: Natural Sleep and Its Seasonal Variations in Three Pre-industrial Societies

Inadequate sleep is associated with marked increase in disease risk (see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!). The authors sought to examine sleep duration, timing, and relation to natural light, ambient temperature, and seasons in three preindustrial human societies: the Hadza in northern Tanzania (hunter-gatherers), the Ju/’hoansi San in Namibia (hunter-gatherers), and the Tsimane in Bolivia (hunter-horticulturalists).

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

In order to measure sleep patterns, members of these three societies wore devices similar to a Fitbit watch (called an Actiwatch-2) for 6-28 days. Sleep was quantified by movement patterns (similar to how a Fitbit measures sleep) in combination with light levels (which a Fitbit does not measure), and the determination of sleep versus awake was determined by a computer program. The participants also wore iButton temperature recorders and temperature recorders were placed near the participants’ sleeping sites in order to accurately measure environmental temperature and humidity.

The authors report that these three societies sleep between 5.7 and 7.1 hours per night, with a sleep period duration of from 6.9 to 8.5 hours per night. Wait, what does that mean?

Sleep Efficiency Vs. Total Sleep

Part of the confusion is that the media quoted the study’s sleep efficiency numbers (5.7-7.1 hours per night) as total sleep, making it seem like these pre-industrial societies spend the same amount of time in bed as we do. This is not what the study actually found! Those low numbers don’t include the time spent in bed with short phases of restlessness and movement, something that happens in both traditional and Westernized societies. If you track sleep with a Fitbit, then you’re well familiar with this phenomenon. For example, if I turn out my light at 10pm and sleep until my alarm goes off at 6:30am, my Fitbit will typically log a little less than 8 hours of sleep. It’s not counting brief arousals during the night or the time it takes me to fall into a nice deep sleep.

The actual sleep periods (the time between first drifting off and officially getting up) ranged from about 7 hours to 8.5 hours. That’s right in line with modern recommendations, and is a much healthier goal for us to aim for.

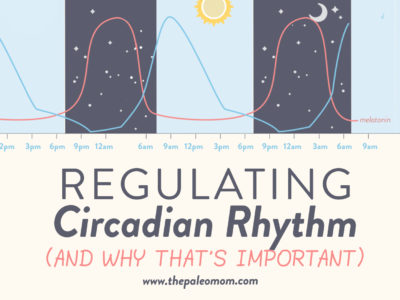

Perhaps even more interesting, when you examine the study’s supplemental material, you see that the participants’ are going “to bed” within a couple of hours of sunset and waking up just before sunrise. Once the sun goes down, movement drops noticeably. The participants are likely participating in quiet interaction and then spending more like 8-10 hours per night in bed, depending on the season.

As a side note, the study also found that these populations slept almost an hour longer on average in the winter than in the summer, suggesting seasonal variation may be totally natural with our sleep patterns! Yes, there’s a scientific reason why it’s super hard to get out of bed on a cold, dark winter day.

Do These Findings Apply to Everyone?

A few other details of this study are important to consider as well. For one, even though three populations were examined, only 94 participants actually had their data collected and used. And, the average age of those participants was fairly young (36.5), with very few people over the age of 55 and virtually no teenagers or children. So, we don’t know for sure how much sleep very young people or the elderly were getting within these societies.

Another issue with this study is that the populations it included were all at similar latitudes, living in areas close to the equator. Could natural sleep patterns be different for those of us living at more extreme latitudes, where winter nights are longer and annual light exposure is different? It turns out, the answer might be yes!

Historical analyses have shown that up until the Industrial Revolution (and scrolling way back through recorded history), something called “bimodal” or “segmented” sleep was dominant in Western civilization. This is where two distinct sleep periods occurred during the night: in general, four hours of sleep followed by one hour or more of wakefulness, followed by another four hours of sleep. Numerous ancient and Medieval references talk about the “first sleep” and “second sleep,” with the period between being used for writing, philosophizing, praying, reflecting, socializing, and other activities. (That period of wakefulness coincided with high levels of the pituitary hormone prolactin, possibly contributing to the sense of peace and creativity people felt during their sleep intermission!)

So, while populations near the equator may naturally sleep uninterrupted, it could be normal for some people at extreme latitudes to rouse during the night (especially in the winter, with longer periods of nighttime darkness)—something we typically diagnose as maintenance insomnia. This is especially true for people with low or no exposure to artificial light and electronics after sundown (as was the case when bimodal sleep was the norm!).

What Does it Mean For Us?

Keep in mind, we shouldn’t be copying the lifestyles (or diets) of our ancestors without evidence that their specific habits are truly health-promoting. But, it’s valuable to see what sleep patterns humans adhere to in the absence of caffeine, electronics, climate-controlled interiors, pharmaceuticals, artificial light, late-night TV, and other features of modern society that help us override our body’s natural signals! And, the results of this particular study confirm what a large body of research also suggests: aiming for 7-8.5 hours of quality sleep every night puts us at levels comparable with hunter-gatherers, and presumably our Paleolithic ancestors.

But, note that sleeping for 7 hours is different than having our head on a pillow for 7 hours. The populations in this study had sleep latency pretty similar to that of Western societies, averaging a half hour to an hour for transitioning from fully awake to deeply asleep. Plus, just like we like to read a book or enjoy some time with our partners before we turn out our bedside lights, pre-industrialized peoples seems to have some wind down times in their sleeping spots as well, meaning that total time in bed is substantially more than total sleep time.

Recall also that we have a bad habit of overestimating how much we’re sleeping, just based on what time we turn our lights off at night and what time our alarms start blaring in the morning. As discussed in Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!, studies show that on average, we report that we got 48 minutes more sleep than we actually did. And, the less sleep we get, the more likely we are to way overreport our sleep, with people who get 5 hours of sleep per night on average overreporting by a whopping 1 hour and 20 minutes.

All told, this study puts the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendations of 7-9 hours of sleep per night right on par with what we see in peoples living in sync with the sun (and free from electronics and artificial light)! Combined with the tremendous body of scientific literature linking inadequate sleep with disease and linking increased sleep with improved cognitive and athletic performance, taking these goals to heart may be the single greatest thing you can do for your health. And, the safest bet is to add an hour or even two to our goal sleep amount to account for the processes of winding down and falling asleep.

Citations

Ekirch AR. “At Day’s Close: Night In Times Past,” New York: Norton, 2006.

Ekirch AR. “Sleep we have lost: pre-industrial slumber in the British Isles.” Am Hist Rev. 2001;106(2):343-86.

Lauderdale, DS, et al. “Sleep duration: how well do self-reports reflect objective measures? The CARDIA Sleep Study” Epidemiology. 2008 November; 19(6): 838–845.

Yetish, et al. “Natural Sleep and Its Seasonal Variations in Three Pre-industrial Societies.” Curr Biol. 2015 Nov 2;25(21):2862-8.