I’m sure you’ve heard the buzz about intermittent fasting, or “IFing”. It’s purported to stimulate healing, increase longevity, balance hormones, increase energy and mental clarity, and provide an easy path to weight loss. Wow, sounds great, where do I sign up!

[insert screeching to a halt noise]

Before you give in to the hype, let’s review the current state of scientific evidence on the pros and cons of intermittent fasting, and why shifting your eating window to early in the day is important.

What Exactly IS Intermittent Fasting?

Intermittent fasting is quite simply defined as the practice of alternating periods of eating and not eating (fasting). There are two popular ways to implement this, both of which have been studied in the scientific literature:

- Alternate day fasting (ADF) – eat normally one day, don’t eat the next, rinse and repeat

- Time-restricted feeding (TRF) – eat all of your meals for the day within a shortened feeding window, typically 4 to 8 hours (fasting for 16 to 20 hours)

There’s also something called fasting-mimicking diets, the best-known example of which is the ketogenic diet, which I don’t support for most applications and have already discussed in detail in Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised and How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut.

The usual goal with intermittent fasting is to reduce your average caloric intake, creating an overall caloric deficit that promotes weightloss (see New Scientific Study: Calories Matter and Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet). Less commonly, people who don’t wish to lose weight squeeze more calories into their feeding window, instead viewing intermittent fasting as a strategy to experience the non-weight loss-related purported benefits.

Rodent Studies of Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting has became a popular fad dietary strategy in recent years thanks to alluring influencer anecdotes saturating the interwebs, supported by compelling research performed in rodents. Studies of intermittent fasting in rats or mice consistently show benefits, including: reducing body weight or body fat, improving insulin sensitivity, reducing glucose and/or insulin levels, lowering blood pressure, improving lipid profiles (reducing LDL and triglycerides, increasing HDL), reducing markers of inflammation (notably the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α), and reducing markers of oxidative stress.

Thanks to my training as a medical researcher, I place high value on rodent studies designed to explore the mechanisms behind an effect already confirmed to co-occur in humans. When a rodent study explains why a phenomenon occurs in humans, it’s excellent data to pay attention to. On the flip side, we’re talking about intervention studies, where the magnitude of an effect is measured (like how well a statin drug reduces LDL cholesterol, or in this case, how well a time-restricted feeding period impacts metabolic and cardiovascular disease risk factors), a healthy dose of skepticism is required. It’s rarely possible to draw a direct line between how well an intervention works in animals and what happens in humans. And, in this case, the results from human trials on intermittent fasting have been decidedly underwhelming.

Still, some mechanisms of action have been elucidated in IF rodent studies. Intermittent fasting in rodents stimulates authophagy. Autophagy is the process by which a starving cell can reallocate nutrients from cell machinery that is not working optimally to fuel more essential cell processes. The cell degrades its own components, including damaged organelles, cell membranes and proteins, in a tightly regulated process. Autophagy can destroy viruses and bacteria within the cell that are resistant to other ways a cell might destroy them. It can even help the cell identify a viral infection that may have otherwise gone undetected. Autophagy plays a crucial role in immunity and inflammation, balancing the beneficial and detrimental effects of immunity and inflammation, and thereby may protect against infectious, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. It may even prevent cells from becoming cancerous. Autophagy plays a normal part in cell growth, development, and homeostasis, helping to maintain a balance between the synthesis, degradation, and subsequent recycling of cellular products. In fact, failure of autophagy is thought to be one of the main reasons for the accumulation of cell damage and aging. Turning on autophagy is extremely beneficial; the result is healthier, more efficient cells, which means a healthier, more efficient body. Do note that autophagy can also be stimulated with exercise and getting sufficient quality sleep (no fasting required!).

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

And, rodent studies have revealed the necessity for aligning a time-restricted feeding window with circadian rhythms (see Regulating Circadian Rhythm (and Why That’s Important)). For example, a 2012 mouse study showed that mice fed a high-fat diet but with their access to food restricted to their normal nocturnal eating times were protected from the obesity, hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and inflammation normally experienced by the mice fed the same diet but with 24/7 access to their food, despite the fact that both groups of mice consumed equivalent amounts of food and calories! (Aside: a high-fat Western-style diet triggers round-the-clock eating patterns in rodents, so if you’re struggling with evening snacking, dialing in the macros and avoiding hyperpalatable foods may help! See Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?, AIP FAQ: Carbohydrate Intake on the Autoimmune Protocol, Because Fiber Wasn’t Awesome Enough: New Science Suggests Fiber Improves Sleep Quality!, and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body.) Human studies looking at Ramadan as a model for intermittent fasting also confirm that more weight is lost with caloric restriction (about three times more!) than intermittent fasting, likely due to the circadian rhythm disrupting effects of eating late in the evening.

There’s also a gut microbiome connection (see What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?). In a 2014 mouse study, normal-chow feeding naturally occurring during the active dark phase resulted in microbiome diversity fluctuations throughout the day (rising with feeding but falling during fasting). Firmicutes species peaked during nocturnal feeding and decreased substantially during daytime fasting (a peak-to-trough ratio of 3:1), while Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia bottomed out during nocturnal feeding but peaked during daytime fasting. In fact, between 20 and 83% of the bacterial species cycled, synced with circadian rhythm and feeding-fasting cycles. Consistent with other studies, mice placed on an unlimited high-fat diet lost their nocturnal feeding habits and experienced significantly blunted cyclical fluctuations in gut bacteria. Yet, mice placed on a high-fat diet but with time-restricted feeding exhibited restored cycles (although some important probiotic strains like Bacillus species didn’t cycle on the high-fat diet even with time-restricted feeding) and decreased the relative abundance of microbes associated with obesity and increased relative amounts of microbes believed to protect against obesity.

Overall, there’s some interesting mechanisms at work here. The question is: To what degree are these mechanisms occurring in humans, and is the effect sufficient in magnitude for humans to benefit from intermittent fasting?

Human Trial Results are Underwhelming

Most studies in humans have shown that intermittent fasting (whether via alternate-day fasting or a time-restricted feeding period) doesn’t provide any additional benefit compared to other diets, with metabolic and cardiovascular benefits attributable solely to the weight lost during the study. So, yes, clinical trials confirm that intermittent fasting can help you lose weight, thanks to the overall reduction in caloric intake (see New Scientific Study: Calories Matter, Portion Control: The Weight Loss Magic Bullet and Paleo for Weight Loss). And, when you’re overweight or obese, losing weight typically also results in improved insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease risk factors (like lower blood pressure and improved serum lipid profiles). (I’ll discuss the handful of human studies showing benefit of intermittent fasting above and beyond weight loss in the next section since they’re limited to those studies that have feeding windows that begin early in the day.)

Viewed through this lens, the real question becomes: is intermittent fasting the easiest or best way to achieve a caloric deficit?

Studies reveal compliance challenges over the long-term for just about any weight loss intervention—losing weight successfully and keeping it off requires a lifestyle overhaul, the formation of lifelong healthy eating habits, behavioral modification, and addressing more than just dietary factors (sleep, stress, and activity are all important for healthy and sustainable weight loss too). When it comes to achieving a caloric deficit, I recommend looking at nutrient-dense and balanced diets that focus primarily on satiating whole foods, so that eating an appropriate amount of calories requires a little less will power. (This is how the Paleo diet can help with weight loss, see Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies.) I discuss the science behind healthy weight loss in detail in my Healthy Weight Loss online course.

NEW! Healthy Weight Loss Online Course!

- Learn how to lose weight in a healthy way, so you can keep it off!

- 2 1/2 hours of video lecture + downloadable slide PDF

- Smart goal setting and measuring weight loss success

- Busting diet myths (the problems with keto, low-carb, low-fat, and low-calorie)

- Get healthy to lose weight (instead of losing weight to get healthy)

Learn More or Get Instant Access

But the human trials on intermittent fasting reveal something worse than lackluster effects: If your time-restricted feeding window starts later in the day, meaning you skip breakfast to prolong your fast, you could be doing more harm than good.

As discussed in Is Breakfast The Most Important Meal of the Day? New Science Has Answers!, a 2017 study used a randomized crossover design to evaluate skipping breakfast versus skipping dinner compared to the standard three meals per day. Time-restricted feeding (either skipping breakfast or skipping dinner) resulted in slightly higher energy expenditure for the day. And while skipping breakfast (but not skipping dinner) increased fat oxidation, it came at the expense of higher inflammatory responses, a whopping a 54% increase in the postprandial HOMA index (meaning increased insulin resistance), and higher blood sugar and insulin levels after lunch. Routinely skipping breakfast increases risk of type 2 diabetes by a whopping 55%, increases risk of cardiovascular disease by 21% and increases all-cause mortality (a general measure of health and longevity) by 32%.

Subsequent studies confirm that, in order to benefit from intermittent fasting, an early feeding window is required.

Early Time-Restricted Feeding

Part of the problem is that influencers and authors who have popularized intermittent fasting have long recommended skipping breakfast (or enjoying a cup of buttered coffee to get you through the morning until your first meal). The research unequivocally shows that the benefits of intermittent fasting are better achieved by skipping dinner rather than by skipping breakfast, a type of intermittent fasting called early time-restricted feeding (or eTRF), meaning your feeding window occurs early in the day. In addition to the 2017 clinical trial mentioned above, two other well-designed clinical trials shed some light on the benefits of this eating pattern.

A well-designed 2018 supervised feeding trial in twelve overweight or obese men with prediabetes, used a cross-over design and matched food intake (with a diet consisting of 50% carbohydrate, 35% fat, and 15% protein) between the eTRF arm and the control arm of the trial, controlling caloric intake so that no weight loss occurred. That’s an important aspect of this study because it allowed the researchers to measure benefits of intermittent fasting with an early feeding window independent of any benefits of losing weight. The study showed that after 5 weeks of eTRF, participants had improved insulin levels, insulin sensitivity, β cell responsiveness, blood pressure, and reduced oxidative stress levels—all good things!

A 2019 clinial trial (reported in two journal articles), also with a randomized cross-over design, compared 4 days of eTRF to control in 11 generally healthy adults (7 men and 4 women) for 4 days. In the first paper, the study authors report no benefit to energy expenditure of eTRF (in contrast to the 2017 study described above), but improved metabolic flexibility, and reduced morning ghrelin and leptin levels, leading to more even-keeled hunger and decreased desire to eat experienced by the participants. The authors conclude that the weight-loss benefits of eTRF are attributable to reduced appetite (making it easier to achieve a caloric deficit and stick to the plan over time). In the second paper, relative to control, eTRF had reduced 24-hour glucose levels (indicating improved insulin sensitivity), increased morning expressing of an aging gene (SIRT1) and an autophagy gene (LC3A), increased evening expression of brain-derived neurotropic factor (BNDF; important for central nervous system health) and MTOR (a major nutrient-sensing protein that regulates cell growth). eTRF also altered the diurnal patterns in cortisol (morning cortisol was elevated, and evening cortisol lowered, which may or may not be desirable depending on stress levels; see Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What Is Adrenal Fatigue?) and the expression of several circadian clock genes. Note that this last effect of intermittent fasting, even with a feeding window early in the day, implies that this is not an appropriate dietary strategy for anyone with unmanaged chronic stress (see also How Stress Undermines Health).

Overall, an argument can be made for early time-restricted feeding as a strategy to improve cardiometabolic parameters above and beyond healthy food choices. But it’s worth also looking at the magnitude of effect compared to other interventions. For example, in the 5-week long 2018 study described above, fasting insulin decreased by 14.5% with a statistical trend towards a reduced HOMA index (but not statistically different, meaning more data is required to validate whether or not there’s an effect). To put this into perspective, most studies show insulin sensitivity decreasing by 15-30% after four or five nights of partial sleep (like not getting enough sleep on weeknights), with one study showing that a single night of partial sleep causes a 25% decrease in insulin sensitivity in healthy people (see 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food). And what about that increase in energy expenditure from intermittent fasting? The 2017 paper described above calculates an extra 91 calories burned daily with intermittent fasting compared to 3 meals per day, equivalent to about 14 minutes of walking. I would argue that we get a lot more bang for our buck by getting enough sleep, living an active lifestyle, and managing stress than we do by adopting an early time-restricted feeding pattern. See The Paleo Lifestyle

But Eating ALL THE TIME Isn’t Good Either

The most popular diets these days seem to be diets of extremes, with the word moderation being viewed as an excuse to not do the hard work of eating healthily. I want to make sure that I’m clear: Just because intermittent fasting isn’t likely to provide much health benefit above and beyond making good food choices, reigning in caloric intake, and dialing in lifestyle factors, that doesn’t mean I support eating at any time or all the time during the day!

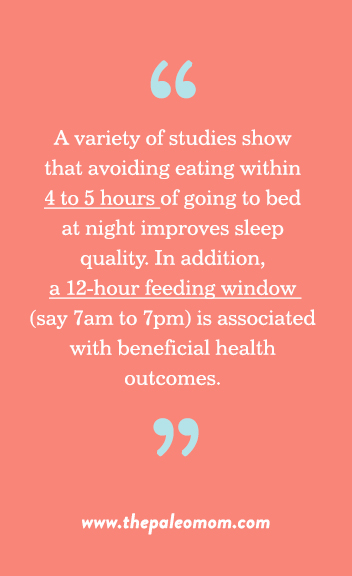

A variety of studies show that avoiding eating within 4 to 5 hours of going to bed at night improves sleep quality. In addition, a 12-hour feeding window (say 7am to 7pm) is associated with beneficial health outcomes (likely due to synchronizing eating with our circadian rhythms). Combined with the research showing metabolic benefits to eating breakfast (see Is Breakfast The Most Important Meal of the Day? New Science Has Answers!), this makes a good case for eating a balanced and complete breakfast soon after waking (say, within the first hour), three nutrient-dense meals per day (spacing meals 4-5 hours apart is great for leptin and ghrelin regulation, see The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin, and The Hormones of Hunger), and making sure dinner is regularly eaten on the early side and avoiding evening snacking.

Turns out that old adage “eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper” is a pretty good way to go!

Citations

Aksungar FB, et al. “Comparison of Intermittent Fasting Versus Caloric Restriction in Obese Subjects: A Two Year Follow-Up.” J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(6):681-685. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0786-y.

Ballon A, et al. “Breakfast Skipping Is Associated with Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes among Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies.” J Nutr. 2019 Jan 1;149(1):106-113. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy194.

Farshchi HR, et al. “Deleterious effects of omitting breakfast on insulin sensitivity and fasting lipid profiles in healthy lean women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):388-96.

Hatori M, et al. “Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet.” Cell Metab. 2012 Jun 6;15(6):848-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019. Epub 2012 May 17.

Horne BD, et al. “Health effects of intermittent fasting: hormesis or harm? A systematic review.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Aug;102(2):464-70. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.109553.

Jakubowicz D, et al. “Effects of caloric intake timing on insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome.” Clin Sci (Lond). 2013 Nov;125(9):423-32. doi: 10.1042/CS20130071.

Jakubowicz D, et al. “Fasting until noon triggers increased postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired insulin response after lunch and dinner in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial.” Diabetes Care. 2015 Oct;38(10):1820-6. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0761. Epub 2015 Jul 28.

Jakubowicz D, et al. “High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women.” Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Dec;21(12):2504-12. doi: 10.1002/oby.20460. Epub 2013 Jul 2.

Jamshed H, et al. “Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans.” Nutrients. 2019 May 30;11(6). pii: E1234. doi: 10.3390/nu11061234.

Ofori-Asenso R, et al. “Skipping Breakfast and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Death: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies in Primary Prevention Settings.” J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2019 Aug 22;6(3). pii: E30. doi: 10.3390/jcdd6030030.

Melkani GC and Panda S. “Time-restricted feeding for prevention and treatment of cardiometabolic disorders.” J Physiol. 2017 Jun 15;595(12):3691-3700. doi: 10.1113/JP273094. Epub 2017 Apr 25.

Moro T, et al.”Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males.” J Transl Med. 2016 Oct 13;14(1):290.

Nas A, et al. “Impact of breakfast skipping compared with dinner skipping on regulation of energy balance and metabolic risk.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jun;105(6):1351-1361. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.151332. Epub 2017 May 10.

Patterson, RE, et al. “Intermittent Fasting and Human Metabolic Health“. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Aug; 115(8): 1203–1212. Published online 2015 Apr 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.018

Ravussin E, et al. “Early Time-Restricted Feeding Reduces Appetite and Increases Fat Oxidation But Does Not Affect Energy Expenditure in Humans.” Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019 Aug;27(8):1244-1254. doi: 10.1002/oby.22518.

Sutton EF, et al. “Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes.” Cell Metab. 2018 Jun 5;27(6):1212-1221.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010. Epub 2018 May 10.

Zarrinpar A, et al. “Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome.” Cell Metab. 2014 Dec 2;20(6):1006-17. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.008.