As fears over covid-19 mount during the already-underway cold and flu season, I feel that it’s important to highlight the positive actions we can each take to naturally support our immune systems. Let me emphasize right out of the gate: These are diet and lifestyle strategies that support immune health and have been shown in scientific studies to reduce susceptibility to infection. These strategies are not a substitute for medical care and if you suspect that you may have covid-19 (or the flu for that matter), it’s incredibly important to call your doctor, and follow their up-to-date advise on testing, isolation and mitigation.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

Covid-19: What We Know So Far – Updated 3/29/20

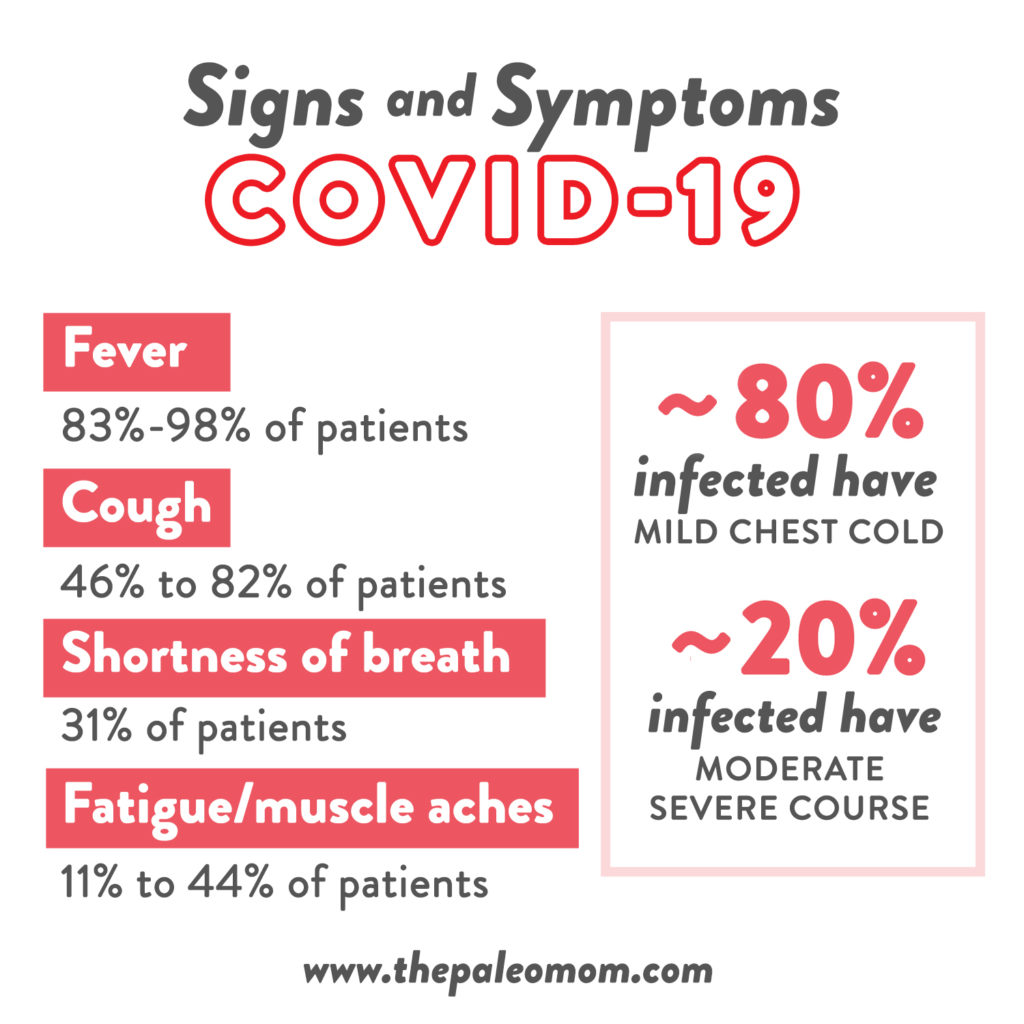

Covid-19 is the name of the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, which has been named SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (its predecessor SARS-CoV was responsible for the 2002 SARS outbreak). The symptoms of covid-19 include fever (present in 83% to 98% of patients), cough (present in 46% to 82% of patients), shortness of breath (present in about 31% of patients), fatigue or muscle aches (present in 11% to 44% of patients), with less common symptoms such as loss of taste or smell, headache, sore throat, abdominal pain and diarrhea also reported. Current estimates are that at least 80% of people infected have a “mild” disease course (which encompasses everything from mild check cold to walking pneumonia), whereas 20% have a moderate to severe disease course, including viral pneumonia requiring hospitalization and respiration support (such as supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation).

Covid-19 is the name of the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, which has been named SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (its predecessor SARS-CoV was responsible for the 2002 SARS outbreak). The symptoms of covid-19 include fever (present in 83% to 98% of patients), cough (present in 46% to 82% of patients), shortness of breath (present in about 31% of patients), fatigue or muscle aches (present in 11% to 44% of patients), with less common symptoms such as loss of taste or smell, headache, sore throat, abdominal pain and diarrhea also reported. Current estimates are that at least 80% of people infected have a “mild” disease course (which encompasses everything from mild check cold to walking pneumonia), whereas 20% have a moderate to severe disease course, including viral pneumonia requiring hospitalization and respiration support (such as supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation).

Analysis of data released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control shows a case fatality rate of 2.3%, but this may be an overestimation due to under-counting of mild cases. As of 3-29-2020, the mortality rate in South Korea, which has done the most wide spread testing of any country so far (they are testing about 10,000 people per day and even have drive-thru test facilities!), is about 1.6%. That’s still nearly 16 times higher than the seasonal flu so far this year. Vulnerable populations include older adults, smokers, and people with pre-existing conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease.

One reason to be concerned about covid-19 is its high morbidity rates, even in age groups where the mortality rate is lower. Data from the CDC compiled between February 12th and March 16th, 2020 show that 14.3% of covid-19 patients aged 20-44 require hospitalization and 2% require ICU admission, even though the mortality rate for this younger age group is only 0.1%. For ages 45-65, about 21% of covid-19 patients require hospitalization and 5% require ICU admission, and mortality is about 1%. In contrast, for those over the age of 75, hospitalization or ICU admission is required in about 40% of cases, and the mortality rate is 10-15%.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

Another reason to be concerned about covid-19 is that it appears to be highly contagious. It is spread primarily via respiratory transmission (there is some data showing other modes of transmission such as fecal transmission are also possible) and the incubation period averages 5 or 6 days, but may range anywhere for 1 to 14 (with one study suggesting the incubation period could even be as high as 24 days). The reproductive number (R0 [pronounced “arr not”], the expected number of secondary cases produced by a single infected person in a susceptible population) is between 2 and 3, which means that, while covid-19 is not a super-hot spreading virus (one that is spread by one patient to many others; for example the R0 of measles in unvaccinated populations is about 18), it also doesn’t look like covid-19 will be self-limiting (i.e., it has a higher pandemic potential). And, there’s new evidence that people infected with SARS-CoV-2 may be contagious for up to several days prior to showing symptoms.

The reason why it’s so important to reduce exposure is because the combination of the highly infections nature of covid-19 and its high morbidity rate means that hospital systems around the world will be easily overwhelmed with the huge influx of patients requiring advanced medical care. This is why we must all contribute to “flattening the curve”, meaning we slow the spread of covid-19 so the number of patients requiring hospital bed and respiratory support at any given times remains below maximum capacity. Continue reading below and read How to Prepare for a Coronavirus Shutdown.

It’s tough to extrapolate what percent of the total population could be affected if current attempts to contain the spread of covid-19 are unsuccessful. Harvard epidemiology professor Marc Lipsitch has been quoted as predicting 40-70% of the global population will get it in the absence of adequate action. How successful can containment efforts be? The infection rate on the Diamond Princess cruise ship was about 19%, with quarantine protocols in place. In contrast, in South Korea where they have done extensive testing and targeted quarantines based on test results, the currently reported infection rate is about 2.4% (~94% of the people they’ve tested so far have tested negative, and the remaining ~4% are waiting for their tests to be processed). To compare, between 3 and 15% of Americans get the seasonal flu each year.

While the situation remains incredibly dynamic and there remain many unknowns about covid-19, there are some actions we can all take now to both reduce our potential exposure and support our immune systems.

Reducing Exposure

First and foremost, you can reduce your exposure by washing your hands frequently and lathering up for a full 20 seconds, making sure to get between fingers and under nails.

First and foremost, you can reduce your exposure by washing your hands frequently and lathering up for a full 20 seconds, making sure to get between fingers and under nails.

A 2016 study looking at the effectiveness of hand-washing on influenza infection showed that proper hand-washing with soap and water at prudent times (like before eating, after using toilet, and after returning home from community activities) reduced the chances of getting the flu from 26% to 3%. Remember that the key here is to lather vigorously, which is far more important than what type of soap you use. In the absence of soap and water, you may opt for a alcohol-based hand sanitizer that is at least 60% alcohol, making sure to use enough for it to take at least 15 seconds to evaporate, again rubbing your hands together vigorously. When washing your hands is an option, that is preferable to hand sanitizer as it is more effective.

Also, avoid touching your eyes and mouth, especially while you’re out and about (or anytime you have unwashed hands); and, practice “social distancing”, meaning avoiding shaking hands, fist bumps, hugging etc. In general, try to maintain a 6-foot distance between yourself and anyone else when you’re out of the house. Clean surfaces in your home, especially high-touch areas like door nobs, drawer pulls, light switches, faucets, and countertops. And, clean your mobile phone daily.

It’s also important to avoid crowded areas, especially where airflow may be limited or recycled, which is why so many events have been cancelled and various state governments are enforcing limits on how many people can gather. If you do feel even a little under the weather, or think that you may have been exposed, do everyone a favor by staying home and practicing self care to get better as efficiently as possible (even if you have a mild case because this helps protect more vulnerable people). And, if you have the ability to stay home and self-isolate, even if you’re healthy and haven’t been exposed, that is a tremendous contribution to current efforts to limit the spread of this virus. This is definitely a time to re-evaluate priorities and do everything we can as individuals not just to protect ourselves, but also our communities.

Priorities for Immune Support

This will probably come as no surprise… the most important things that you can do to support your immune system so that it can effectively beat an infectious disease are the same things that support your overall health: get enough sleep, manage stress, and live an active lifestyle while avoiding overtraining (see The Paleo Lifestyle). These are also the healthy lifestyle choices that are the easiest to let slide when life gets busy.

So, a positive way to channel anxieties about covid-19 or influenza (or the next nerve-racking potential pandemic) is as motivation to finally address lifestyle factors that might not be as dialed in as they could be. And, any effort to implement a healthy lifestyle is likely to pay off, as we can see from scientific studies looking at how sleep, stress and activity affect our susceptibility to colds, the flu, and pneumonia.

#1 – Get Enough Sleep

#1 – Get Enough Sleep

In my popular online program, Go to Bed, I discuss all the many ways that sleep impacts our health (also see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!) – and the immune system is a major mechanism behind all of them! Just plain old “not getting enough sleep” (see Sleep Requirements and Debt: How do you know how much sleep you need?) causes inflammation. Even just three consecutive nights of inadequate sleep can cause measurable increases in markers of inflammation in the blood, straining our immune system so it’s less able to respond to a pathogen.

Our immune system cycles with our circadian rhythm, along with antibody formation (the way our bodies know to respond to super-specific invaders, like influenza or SARS-CoV-2), which predominantly takes place during sleep. So, someone who is not getting enough sleep is also not adequately forming antibodies. As a result, simply getting adequate sleep can protect you from infection. Studies examining differences or changes in sleep quality have found similar differences in immune function; basically, sleep quality and quantity is essential if we’re trying to protect ourselves from the flu season!

Some studies have specifically looked at how our regular sleep patterns impact our susceptibility to infection. A 2015 study in 164 healthy people, looked at how sleep impacted their risk of infection and clinical symptoms after being exposed to the common cold-causing rhinovirus (the researchers literally administered active rhinovirus up the participants noses!). After correcting for all other potential contributors, sleep duration was the biggest predictor of whether or not the people would get a cold (not sleep fragmentation or sleep efficiency). Sleeping less than 5 hours per night increased chances of developing a cold by 4.5X compared to 7 or more hours of sleep! Yikes! And getting 5 to 6 hours per night wasn’t much better; the risk was still 4.24X higher than people who got 7 or more hours sleep. And getting 6 to 7 hours of sleep per night still increased risk of getting the cold by 66% compared to 7 or more hours. Similarly, a 2012 prospective study in female nurses aged 37-57 with no pre-existing conditions showed those who routinely slept less than 5 hours per night had a 70% higher risk of getting pneumonia over the 4-year study period than those who routinely slept 8 hours per night.

The single best thing most of us can do to make sure we’re getting enough sleep (8 hours really is a good rule of thumb) is have a grown-up bedtime and stick to it. I suggest a bedtime that is 8.5 to 9 hours before your alarm goes off in the morning, which allows for the normal 30ish minutes to fall asleep and normal arousals during the night. If the notion of prioritizing sleep is totally overwhelming, my e-book Go to Bed is loaded with tips and tricks (that include everything from tiny tweaks to lifestyle overhauls!). Also see 4 Biohacks for Better Sleep and 5 Ways to Improve Your Bedroom Environment for Sleep.

#2 – Manage Stress

The best understood mechanism of the negative health impact of chronic stress is how it impacts immune function (see How Stress Undermines Health and Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What Is Adrenal Fatigue?).

Cortisol, the main stress hormone produced by our adrenal glands, alters the chemical messengers of inflammation (called cytokines) secreted by cells in the immune system. This changes how the immune system communicates with itself, turning on some aspects of the immune system, while turning off other aspects of the immune system. There are a wealth of studies to show that high cortisol causes inflammation. Chronic stress has been unequivocally shown to increase susceptibility to a variety of conditions, including autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, depression, cancer and infection.

In a 1991 study, participants’ stress levels were assessed based on a questionnaire before nasal administration of one of 5 different viruses that cause the common cold (1 strain coronavirus [not SARS-CoV-2], 3 strains of rhinovirus, and 1 strain of respiratory syncytial virus[RSV]). Rate of infection was 5.81X higher in highest stress participants compared to lowest stress (independent of which virus they were exposed to), and rate of developing clinical cold (meaning a symptomatic infection) was 2.16X higher. Another yikes! An 1966 prospective study of employees who worked at a military research instillation evaluated their stress levels six months before flu season and categorized them as either high stress or low stress. The high stress employees were about 3X more likely to get the flu the next season compared to the low stress employees. A more recent 2019 study looked at susceptibility to life-threatening infections in people with stress-related disorders (including post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], acute stress reaction, and adjustment disorder) compared to their full siblings without stress-related disorders and compared to matched controls from the general population. A stress-related disorder diagnosis increased risk of life-threatening infections by 47% compared to siblings and 58% compared to the general population. PTSD specifically, increased risk of life-threatening infection by 92% compared to siblings and 95% compared to the general population.

Mindfulness practice is a well-studied and effective strategy for managing stress (apps like Calm and Headspace make mindfulness practice very accessible, and I recommend the book Mindsight by Dan Siegel) and can even be helpful for stress-related disorders (as can therapies such as EMT and EMDR). Its also helpful to reduce your stressor load if possible, including reducing commitments if possible but also exposure to chemical stressors (like alcohol and tobacco), environmental stressors (like extreme temperatures) and sensory stressors (like crowded places). Other strategies to improve resilience to stress include: time in nature, exercise, laughing, cuddling with a pet, hugging and cuddling with a loved one, and making time for hobbies. There’s also a link between sleep and stress: getting enough sleep helps regulate the stress response and managing stress helps improve sleep quality. So, it’s always helpful to work on improving sleep and stress levels at the same time.

#3 – Get Moderate-Intensity Exercise

Exercise is one of those moderate stressors that can be really good for our bodies (see The Benefits of Gentle Movement and The Importance of Exercise). All in all, it’s important to establish an exercise routine that incorporates a variety of movements that are both aerobic (generally, “cardio”-type exercises) and anaerobic (resistance training like weightlifting) in nature. There are many other reasons to have movement variability, including increased metabolic benefits and reduced risk of injury. Apart from this, studies have demonstrated that regular exercise promotes improved immune system function by reducing inappropriate cytokine activity, improving white blood cell function, and regulating cortisol release (both of which are also related to systematic inflammation – another reason why we need to tackle our health from all of these angles!). Plus, there is added benefit to light exercise when we’re already feeling a little sniffly: the activity may flush microbes out of the lungs and increase body temperature to help fight the infection!

Exercise is one of those moderate stressors that can be really good for our bodies (see The Benefits of Gentle Movement and The Importance of Exercise). All in all, it’s important to establish an exercise routine that incorporates a variety of movements that are both aerobic (generally, “cardio”-type exercises) and anaerobic (resistance training like weightlifting) in nature. There are many other reasons to have movement variability, including increased metabolic benefits and reduced risk of injury. Apart from this, studies have demonstrated that regular exercise promotes improved immune system function by reducing inappropriate cytokine activity, improving white blood cell function, and regulating cortisol release (both of which are also related to systematic inflammation – another reason why we need to tackle our health from all of these angles!). Plus, there is added benefit to light exercise when we’re already feeling a little sniffly: the activity may flush microbes out of the lungs and increase body temperature to help fight the infection!

A 2006 study of overweight and obese sedentary postmenopausal women, researchers compared 45 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 5 days per week to 45 minutes of stretching only (also 5 days per week) over the course of a year. In the final three months of the study, the stretching only group had a 3X higher likelihood of getting a cold compared to the exercise group. But, you don’t have to work out for 9 straight months before your immune system benefits. In a 2005 study of healthy women aged 45-65 year, the researchers looked at how exercising for 30 minutes at a moderate intensity (60% max heart rate) 5 times per week affected rates of upper respiratory infections over 12 weeks. Exercising resulted in a 25% fewer episodes of upper respiratory infections compared to the control group. Even getting out for a walk is beneficial. In a 1993 study evaluating risk of common cold in older subjects over a 12-week period, the researchers found that the incidence of the common cold was 8% in elderly women who already exercised at moderate intensity regularly, 21% in previously sedentary elderly women who walked for 40 minutes 5 times a week during the study, and 50% in the sedentary control subjects.

Avoiding high-intensity and strenuous workouts is important though (see Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut). It’s well established that athletes have a higher risk of upper respiratory infections, especially during periods of heavy training and competition. Studies have shown that this may be due to an increased window of susceptibility to infection in the hours following strenuous exercise, due to a temporary suppression of immune function.

Walking is a great place to start if you’re not very active right now, aiming for at least 150 minutes per week (that’s a 30-minute walk 5 times per week). If you’re already a gym buff, adding in a daily walk can still be very beneficial for immune health and stress management (and it’s important to re-evaluate whether or not those tough workouts are the best idea right now). For more activity guidelines, see The Importance of Exercise.

Nutrients for Immune Support

I discuss the role of micronutrients (vitamins, minerals and phytochemicals) in immune function in the context of chronic illness in great detail in The Paleo Approach and The Autoimmune Protocol Lecture Series. But, let’s look at how some important micronutrients can specifically make us more resilient to infection by supporting healthy immune function.

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a vital component of both the innate and adaptive immune response. This vitamin maintains the structural integrity of mucosal cells (think the lining of your respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract!), so it is essential for keeping our first line of defense physically intact. Plus, it is needed for proper function of a host of immune cells (i.e., natural killer cells, macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and more!). In fact, vitamin A was identified as an immune modulating nutrient as early as 1928! Vitamin A insufficiency is well-known to increase infection rate and mortality, especially in school-age children. And, vitamin A supplementation has been shown to improve antibody production in response to various vaccines. Also, many types of infection have been shown to deplete serum vitamin A, so our nutritional need for vitamin A may be higher during an infection (more data is needed to quantify this).

Vitamin A is a vital component of both the innate and adaptive immune response. This vitamin maintains the structural integrity of mucosal cells (think the lining of your respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract!), so it is essential for keeping our first line of defense physically intact. Plus, it is needed for proper function of a host of immune cells (i.e., natural killer cells, macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and more!). In fact, vitamin A was identified as an immune modulating nutrient as early as 1928! Vitamin A insufficiency is well-known to increase infection rate and mortality, especially in school-age children. And, vitamin A supplementation has been shown to improve antibody production in response to various vaccines. Also, many types of infection have been shown to deplete serum vitamin A, so our nutritional need for vitamin A may be higher during an infection (more data is needed to quantify this).

Foods rich in vitamin A include liver, other organ meats, fish and shellfish. See also Genes to Know About: Vitamin A Conversion Genes and check out the , available from Smidge™ (formally Corganic), a whole food-based supplement option for vitamin A.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C might be the most well-known immune support vitamin of them all. The main function that vitamin C holds is to act as an antioxidant within certain immune cells; this process actually creates reactive oxygen species to kill pathogens. Since we cannot synthesize our own vitamin C, it is crucial that we get enough of it in our food or through supplementation. However, a large meta-analysis have revealed that up to 2 grams daily vitamin C supplementation doesn’t reduce the incidence of the common cold, the exception being people under high physical stress including marathon runners, skiers and soldiers who do see about a 50% decrease in cold incidence. For the general population though, vitamin C supplementation shortens cold duration by an average of 8% in adults and 14% in children, and decreases the severity of the cold by about 5%.

Vitamin C might be the most well-known immune support vitamin of them all. The main function that vitamin C holds is to act as an antioxidant within certain immune cells; this process actually creates reactive oxygen species to kill pathogens. Since we cannot synthesize our own vitamin C, it is crucial that we get enough of it in our food or through supplementation. However, a large meta-analysis have revealed that up to 2 grams daily vitamin C supplementation doesn’t reduce the incidence of the common cold, the exception being people under high physical stress including marathon runners, skiers and soldiers who do see about a 50% decrease in cold incidence. For the general population though, vitamin C supplementation shortens cold duration by an average of 8% in adults and 14% in children, and decreases the severity of the cold by about 5%.

The foods richest in vitamin C are citrus fruits, bell peppers, acerola cherries, and wild rose hips.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is another well-known immune modulator that is worth paying attention to. Normal levels of vitamin D promote genetic expression of several immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes (this means that without vitamin D present, the amount of these cells that are generated is much less! That leads to a sub-optimal immune system, to say the least). There is now considerable evidence that suboptimal vitamin D status is associated with compromised immunity and increased infection risk. A meta-analysis showed that daily vitamin D supplementation (400IU to 4000IU daily, average 1600IU) decreased risk of upper respiratory infection by 49% (bolus supplementation was not as effective and only decreased upper respiratory infection incidence by 14%).

Vitamin D is another well-known immune modulator that is worth paying attention to. Normal levels of vitamin D promote genetic expression of several immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes (this means that without vitamin D present, the amount of these cells that are generated is much less! That leads to a sub-optimal immune system, to say the least). There is now considerable evidence that suboptimal vitamin D status is associated with compromised immunity and increased infection risk. A meta-analysis showed that daily vitamin D supplementation (400IU to 4000IU daily, average 1600IU) decreased risk of upper respiratory infection by 49% (bolus supplementation was not as effective and only decreased upper respiratory infection incidence by 14%).

Optimal serum vitamin D levels are between 50 and 70 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). If you’re insufficient or deficient, it can be tough to get enough vitamin D3 from sun exposure and foods (fish, shellfish and pastured meats do contain some vitamin D), so consider supplementing with vitamin D3 (5,000 IU daily is a standard dose to address deficiency but ask your healthcare provider for a recommendation based on your personal health history) and recheck every three months to make sure you don’t overshoot the mark. Vitamin D levels in excess of 100 ng/mL can also cause health problems. I recommend EverlyWell for at-home vitamin D testing.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin (meaning that we can store it in our fat and that it is absorbed with dietary fat) that is also responsible for maintaining proper immune function. Specifically, alpha-tocopherol (one of the forms of vitamin E) is known to prevent oxidation or damage to cell membranes and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which protects against systemic inflammation. A clinical trial of independently-living elderly people showed that supplementation with 200IU of vitamin E daily decreased the rate of infections by about 30%, including a 22% reduction in incidence of the common cold.

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin (meaning that we can store it in our fat and that it is absorbed with dietary fat) that is also responsible for maintaining proper immune function. Specifically, alpha-tocopherol (one of the forms of vitamin E) is known to prevent oxidation or damage to cell membranes and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which protects against systemic inflammation. A clinical trial of independently-living elderly people showed that supplementation with 200IU of vitamin E daily decreased the rate of infections by about 30%, including a 22% reduction in incidence of the common cold.

Foods rich in vitamin E include avocados, olives, nuts and seeds.

Zinc

Zinc, one of the dietary minerals, is also important in maintaining immune system function, because it is needed for both development and function of immune cells. Like vitamin C, zinc is not stored in the body, so regular consumption of foods that contain zinc is essential for an optimal immune system. Similar to vitamin A, zinc deficiency is associated with increased infection rate and zinc supplementation is known to improve antibody titers after vaccination. In a 2006 clinical trial, children were given zinc (as zinc sulfate, 15mg daily increased to 30mg at the onset of a cold) and followed for 7 months. The number of colds in the zinc group was 30% lower than in the control group, and zinc supplementation shortened the duration of the cold and the severity of symptoms. And, the proportion of children with no colds during the study period was 33% in the zinc group versus 14% in the control group. In a 2007 study of elderly nursing home residents, having normal serum zinc levels reduced the rate of pneumonia by 50% compared to low zinc levels (normal zinc was 70 microg/dL or higher).

Zinc, one of the dietary minerals, is also important in maintaining immune system function, because it is needed for both development and function of immune cells. Like vitamin C, zinc is not stored in the body, so regular consumption of foods that contain zinc is essential for an optimal immune system. Similar to vitamin A, zinc deficiency is associated with increased infection rate and zinc supplementation is known to improve antibody titers after vaccination. In a 2006 clinical trial, children were given zinc (as zinc sulfate, 15mg daily increased to 30mg at the onset of a cold) and followed for 7 months. The number of colds in the zinc group was 30% lower than in the control group, and zinc supplementation shortened the duration of the cold and the severity of symptoms. And, the proportion of children with no colds during the study period was 33% in the zinc group versus 14% in the control group. In a 2007 study of elderly nursing home residents, having normal serum zinc levels reduced the rate of pneumonia by 50% compared to low zinc levels (normal zinc was 70 microg/dL or higher).

The foods highest in zinc are oysters and liver. Check out Oysterzinc™, available from Smidge™ (formally Corganic), a whole food-based supplement option for zinc.

—

Other immune health nutrients include selenium, copper, manganese, iron, and B vitamins (especially B6, B9 and B12). While deficiency is any of these can increase susceptibility to infection, supplementation has either yielded mixed and context-dependent results (worsening outcomes for some and improving outcomes for others) or null effects in clinical trials. So, it’s important to get sufficient levels of these micronutrients from whole food sources, and in general, supplementation is not advised. There’s also preliminary evidence that high intake of polyphenols can help reduce infection risk, although more data is needed (see Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?, Elevating Mushrooms to Food Group Status and Coffee as a Mediator of Health & Longevity).

You’ll note that nutrient supplementation (except possibly vitamin D) has a far smaller impact on infection susceptibility than the lifestyle factors discussed above. When it comes to nutritional strategies to support immune function, the most important action item is to avoid nutrient deficiencies. This is already a key principle of the Paleo Template and can be achieved by focusing on the most nutrient dense foods available to us, eating 8+ servings per day of fresh vegetables and fruit; plus organ meat, fish, shellfish, healthy fats, herbs, spices, and rounding out with other high-quality meats. Read more in The Importance of Nutrient Density, 7 Nutrients You’re Probably Deficient In, 8 Nutrients for Leaky Gut, and 10 Nutrients that Can Help You Burn Fat.

It’s also worth noting that studies show high consumption of vegetables and fruit are independently beneficial for reducing upper respiratory infections, which means it’s good to eat both. My regular readers know that I don’t support low-carb or ketogenic diets for most applications (see Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised, How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut, The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body, and Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding). And, we can add infection susceptibility to the list of concerns with low-carb dietary implementation. In athletes, increasing carbohydrate consumption (30-60 grams per hour) prior to and during strenuous activity has been shown to decrease the infection susceptibility window post-exercise. Also in athletes, rates of infection are lower among those who consume 3 or more servings of fruit per day compared to those who consume less than 2.

What About Supplements?

What About Supplements?

I firmly believe that the above lifestyle factors and nutrient focus (from whole foods!) are by far the most important priorities, and I hesitate to even include a section on supplements within this post.

In fact, there’s very few supplements with antiviral properties tested in humans in relevant infections that are even worth discussing. And, please note that none of them have been tested against SARS-CoV-2! For example, I personally take medicinal mushroom extracts (see The Power of Medicinal Mushrooms: An Overview) and bee propolis (see Why Bee Products Are Great for the Gut Microbiome) for general immune support; but even though they have antiviral properties proven in vitro (isolated cells) or in animal models, their efficacy against relevant infections has not been tested in humans. Again, dialing in sleep, stress management and activity along with avoiding nutrient deficiencies and prudent measurements to prevent exposure like hand washing and social distancing are the most important action items.

Probiotics

Whether you get your probiotics from fermented foods or take a supplement, there’s evidence to support reduced rates of upper respiratory infections. For example, Koreans who consume 108-180 grams daily of kimchi had a 19% decreased risk of rhinitis (runny nose, usually caused by the common cold) compared to those who consumed less than 24 grams daily. And a 2011 meta-analysis of prophylactic probiotic supplementation showed a 42% reduction in people suffering at least one upper respiratory infection (and a 47% reduction for 3+ upper respiratory infections). Most of this research has been performed with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species (I recommend the probiotics, available from Smidge™, formally Corganic), but there’s also research showing Bacillus coagulans can reduce upper respiratory infection rates and Bacillus subtilis can reduce influenza (I recommend Just Thrive probiotic which contains both Bacillus coagulans and Bacillus subtilis).

Overall, the strongest case is for supporting a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. Gut microbiome superfoods include: vegetables of all kinds (roots and tubers, cruciferous veggies, leafy greens, parsley family, onion family, etc.), fruit, mushrooms, nuts and seeds, extra virgin olive oil, fish, shellfish, organ meat, grass-fed meat, and fermented foods. Also, see What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?, The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, The Benefits of Probiotics, Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome, Why Fish is Great for the Gut Microbiome, Why Crickets Are Great for the Gut Microbiome, Water Quality and the Gut Microbiome, The Importance of Vegetables, The Fiber Manifesto-Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?, and The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!

Elderberry

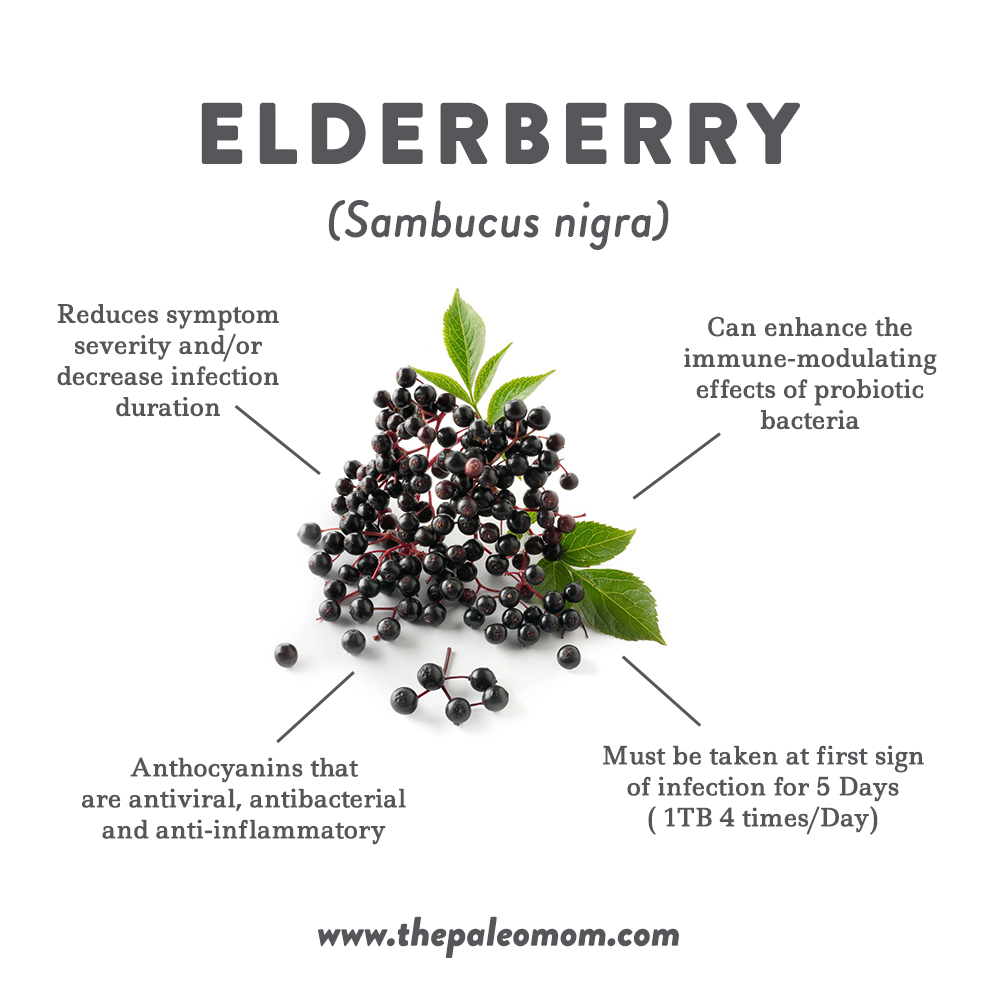

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) extracts have been studied as a short-term intervention for colds, the flu, and upper respiratory infections. Elderberry has not been established as safe for long-term use, nor has it been shown to prevent infections. Instead, taking elderberry for 5 days at the first sign of symptoms has been shown to reduce symptom severity and/or decrease infection duration. A 2004 study showed that elderberry syrup (1 tablespoon 4 times daily for 5 days, taken at first sign of infection) could shorten the duration of influenza symptoms by 4 days. A 2016 study showed that elderberry extract could shorten the duration of the common cold and reduce severity of symptoms. And a 2019 meta-analysis showed that elderberry extract is effective at reducing upper respiratory infection symptoms, with additional studies showing that the mechanism may be direct viral inhibition.

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) extracts have been studied as a short-term intervention for colds, the flu, and upper respiratory infections. Elderberry has not been established as safe for long-term use, nor has it been shown to prevent infections. Instead, taking elderberry for 5 days at the first sign of symptoms has been shown to reduce symptom severity and/or decrease infection duration. A 2004 study showed that elderberry syrup (1 tablespoon 4 times daily for 5 days, taken at first sign of infection) could shorten the duration of influenza symptoms by 4 days. A 2016 study showed that elderberry extract could shorten the duration of the common cold and reduce severity of symptoms. And a 2019 meta-analysis showed that elderberry extract is effective at reducing upper respiratory infection symptoms, with additional studies showing that the mechanism may be direct viral inhibition.

Several studies have confirmed that the anthocyanins from elderberry have antiviral, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Plus, elderberry can enhance the immune-modulating effects of probiotic bacteria like Lactobacillus acidophilus. There’s mixed data on how elderberry extract may impact immune function, specifically the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Two in vitro studies (one from 2001 and one from 2019) in naive (not stimulated) human white blood cells have shown increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, including one study showing a 200-fold increase in interleukin-6 (IL-6), and a 60-fold increase in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). A contrasting 2019 in vitro study in endotoxin (LPS)-stimulated human macrophages showed a dose-dependent decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including a 60% decrease in IL-6 and a 52% decrease in TNF-α.

There has only been one human study looking at proinflammatory cytokines in humans taking elderberry extract. In this 2019 study, healthy postmenopausal women too 500 mg per day of elderberry extract for 12 weeks, or a placebo. There was no statistically significant change to their serum IL-6 nor TNF-α (if anything there was a trend downwards) nor C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation). There was also no significant change in biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk, kidney function or liver function.

There has been some concern expressed in our community that elderberry extract may contribute to a cytokine storm, thereby increasing risk of a severe course of covid-19. Cytokines are chemical messengers of inflammation, some with proinflammatory properties (like the aforementioned IL-6 and TNF-α) and some with anti-inflammatory properties. A cytokine storm is an excessive or uncontrolled release of proinflammatory cytokines, that may contribute to the over-activation of the immune system that occurs in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (the complications causing death from covid-19, which I just happened to research during my Ph.D. and first postdoctoral research fellowship). Cytokine storms are believed to occur in a subset of critically ill covid-19 patients, with serum IL-6 being a strong predictor of survival. (These studies are laying the groundwork to test critically ill patients and treat with corticosteroids if their IL-6 and ferritin are elevated, even though corticosteroids are otherwise contraindicated for viral infections including covid-19. To my knowledge, there has yet to be a clinical trial evaluating whether or not corticosteroids may benefit a subset of critically ill covid-19 patients). Cytokine storms also contribute to mortality from the seasonal flu, in which elderberry does not seem to increase the risk; however, it’s important to note that high-risk populations are never included in these sorts of clinical trials. Over all, I think the fear that elderberry extract may cause a cytokine storm is not supported by the literature, but its prophylactic use isn’t either.

Looking for More Info?

I’m receiving a ton of thoughtful questions about covid-19 preparedness via Facebook, Instagram and my weekly newsletter. So to answer them, I’m created a free online public lecture, titled “Immune Health on a Budget in the Face of Covid-19” that goes into even more detail on how we can support our immune systems and decrease our susceptibility to infection. You can sign up to watch the replay for free below. If you have specific questions that you would also like answered, the best way to get them to me is via my social media accounts or by replying to my weekly newsletter.

Citations

Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014 Feb 18;186(3):190-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121442. Epub 2014 Jan 27.

Anaya-Loyola MA, Enciso-Moreno JA, López-Ramos JE, García-Marín G, Orozco Álvarez MY, Vega-García AM, Mosqueda J, García-Gutiérrez DG, Keller D, Pérez-Ramírez IF. Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6068 decreases upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract symptoms in healthy Mexican scholar-aged children by modulating immune-related proteins. Food Res Int. 2019 Nov;125:108567. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108567

Aukrust P, Muller F, Ueland T, Svardal AM, Berge RK, Froland SS. Decreased vitamin A levels in common variable immunodeficiency: vitamin A supplementation in vivo enhances immunoglobulin production and downregulates inflammatory responses. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30(3):252-259.

Baeke F, Etten EV, Overbergh L, Mathieu C. Vitamin D3 and the immune system: maintaining the balance in health and disease. Nutr Res Rev. 2007;20(1):106-118.

Bergman P, Lindh AU, Björkhem-Bergman L, Lindh JD. Vitamin D and Respiratory Tract Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2013 Jun 19;8(6):e65835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065835.

Bhaskaram P. Micronutrient malnutrition, infection, and immunity: an overview. Nutr Rev. 2002 May;60(5 Pt 2):S40-5.

Brennan A, Katz DR, Nunn JD, et al. Dendritic cells from human tissues express receptors for the immunoregulatory vitamin D3 metabolite, dihydroxycholecalciferol. Immunology. 1987;61(4):457-461.

Chubak J, McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Wener MH, Yasui Y, Velasquez M, Wood B, Rajan KB, Wetmore CM, Potter JD, Ulrich CM. Moderate-intensity exercise reduces the incidence of colds among postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2006 Nov;119(11):937-42.

Ciloğlu F. The effect of exercise on salivary IgA levels and the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections in postmenopausal women. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2005;15(5-6):112-6.

Cohen S, Tyrrell DA, Smith AP. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 29;325(9):606-12.

Cohen S. Psychological stress and susceptibility to upper respiratory infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Oct;152(4 Pt 2):S53-8.

Davison G, Kehaya C, Wyn Jones A. Nutritional and Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Immunity. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014 Nov 25;10(3):152-169. doi: 10.1177/1559827614557773.

Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19-New Insights on a Rapidly Changing Epidemic. JAMA. 2020 Feb 28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3072.

Dhur A, Galan P, Hercberg S. Folate status and the immune system. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1991;15(1-2):43-60.

Frøkiær H, et al. Astragalus Root and Elderberry Fruit Extracts Enhance the IFN-β Stimulatory Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Murine-Derived Dendritic Cells. PLoS One. 2012; 7(10): e47878.

Hao Q, Lu Z, Dong BR, Huang CQ, Wu T. Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;(9):CD006895. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub2.

Hawkins J, Baker C, Cherry L, Dunne E. Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra) supplementation effectively treats upper respiratory symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2019 Feb;42:361-365. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.12.004. Epub 2018 Dec 18.

Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD000980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4.

Hemilä H, Virtamo J, Albanes D, Kaprio J. The effect of vitamin E on common cold incidence is modified by age, smoking and residential neighborhood. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006 Aug;25(4):332-9.

Kakanis MW, Peake J, Brenu EW, Simmonds M, Gray B, Hooper SL, Marshall-Gradisnik SM. The open window of susceptibility to infection after acute exercise in healthy young male elite athletes. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2010;16:119-37.

Kearns MD, Alvarez JA, Seidel N, Tangpricha V. Impact of vitamin D on infectious disease. Am J Med Sci. 2015 Mar;349(3):245-62. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000360.

Kurugöl Z, Akilli M, Bayram N, Koturoglu G. The prophylactic and therapeutic effectiveness of zinc sulphate on common cold in children. Acta Paediatr. 2006 Oct;95(10):1175-81.

Kwon YS, Park YK, Chang HJ, Ju SY. Relationship Between Plant Food (Fruits, Vegetables, and Kimchi) Consumption and the Prevalence of Rhinitis Among Korean Adults: Based on the 2011 and 2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. J Med Food. 2016 Dec;19(12):1130-1140.

Lanfranco F, Ghigo E, Strasburger CJ. Hormones and Athletic Performance. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier;2016:chap 26.

Liu M, Ou J, Zhang L, Shen X, Hong R, Ma H, Zhu BP, Fontaine RE. Protective Effect of Hand-Washing and Good Hygienic Habits Against Seasonal Influenza: A Case-Control Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Mar;95(11):e3046. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003046.

McGill JL, Kelly SM, Guerra-Maupome M, Winkley E, Henningson J, Narasimhan B, Sacco RE. Vitamin A deficiency impairs the immune response to intranasal vaccination and RSV infection in neonatal calves. Sci Rep. 2019 Oct 22;9(1):15157. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51684-x.

Meydani SN, Barnett JB, Dallal GE, Fine BC, Jacques PF, Leka LS, Hamer DH. Serum zinc and pneumonia in nursing home elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Oct;86(4):1167-73.

Meydani SN, Han SN, Hamer DH. Vitamin E and respiratory infection in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Dec;1031:214-22.

Moriguchi S, Muraga M. Vitamin E and immunity. Vitam Horm. 2000;59:305-336.

Patel SR, Malhotra A, Gao X, Hu FB, Neuman MI, Fawzi WW. A prospective study of sleep duration and pneumonia risk in women. Sleep. 2012 Jan 1;35(1):97-101. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1594.

Prather AA, Janicki-Deverts D, Hall MH, Cohen S. Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. Sleep. 2015 Sep 1;38(9):1353-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4968.

Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020 Feb 26:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433.

Song H, Fall K, Fang F, Erlendsdóttir H, Lu D, Mataix-Cols D, Fernández de la Cruz L, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Gottfreðsson M, Almqvist C, Valdimarsdóttir UA. Stress related disorders and subsequent risk of life threatening infections: population based sibling controlled cohort study. BMJ. 2019 Oct 23;367:l5784. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5784.

Starosila D, Rybalko S, Varbanetz L, Ivanskaya N, Sorokulova I. Anti-influenza Activity of a Bacillus subtilis Probiotic Strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 Jun 27;61(7). pii: e00539-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00539-17. Print 2017 Jul.

Thornton KA1, Mora-Plazas M, Marín C, Villamor E. Vitamin A deficiency is associated with gastrointestinal and respiratory morbidity in school-age children. J Nutr. 2014 Apr;144(4):496-503. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.185876. Epub 2014 Feb 5.

Tiralongo E, Wee SS, Lea RA. Elderberry Supplementation Reduces Cold Duration and Symptoms in Air-Travellers: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2016 Mar 24;8(4):182. doi: 10.3390/nu8040182.

Ulbricht C, Basch E, Cheung L, et al. An evidence-based systematic review of elderberry and elderflower (Sambucus nigra) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. J Diet Suppl. 2014;11(1):80-120.

Vallance S. Relationships between ascorbic acid and serum proteins of the immune system. Br Med J. 1977;2(6084):437-438.

Waknine-Grinberg JH, et al. The immunomodulatory effect of Sambucol on leishmanial and malarial infections. Planta Med. 2009 May;75(6):581-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185357. Epub 2009 Feb 12.

Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, et al. Position statement. Part one: immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:6-63. PMID: 21446342

Weiss G, Carver PL. Role of divalent metals in infectious disease susceptibility and outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018 Jan;24(1):16-23. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.01.018. Epub 2017 Jan 29.

Zakay-rones Z, Thom E, Wollan T, Wadstein J. Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J Int Med Res. 2004;32(2):132-40.

Zakay-Rones Z, Thom E, Wollan T, Wadstein J. Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J Int Med Res. 2004 Mar-Apr;32(2):132-40.

Zasloff M. Fighting infections with vitamin D. Nat Med. 2006;12(4):388-390.

Zittermann A, Pilz S, Hoffmann H, März W. Vitamin D and airway infections: a European perspective. Eur J Med Res. 2016 Mar 24;21:14. doi: 10.1186/s40001-016-0208-y.