You may or may not have seen a brief Facebook post I wrote about a week ago regarding an exciting hot-off-the-presses scientific paper that totally blew me away—so much so that I’ve updated my Go to Bed 14-Day Sleep Challenge to reflect this new information! The paper is the very first to draw any kind of link between how much protein, fat and fiber you eat and how well you sleep.

It’s no secret that I have a serious obsession with sleep (yeah, have you seen my epic, 280+ page e-book, Go to Bed? If not, where have you been?). The complicated relationship that we have with our sleep is a very real, very well-studied thing. We know that our sleep quality and duration have a huge impact on every organ system in the body (Seriously. That includes our immune system, blood sugar regulation, cardiovascular system… and even the way our minds operate, too!), and we know that many lifestyle factors of the modern age are majorly disrupting our sleep (trust me, it’s not just the blue light from technology). Yet, we’re still trying to figure out some of the details, including both the mechanisms behind how sufficient sleep protects health (and inadequate sleep destroys it) and what choices to make to support the healthiest sleep – and while we know that there are an incredible number of factors at play for each of us, we now have an additional clue as to one easy step that might improve sleep for many people.

That’s right: a brand-new and very exciting study just published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine gives us even more details about what to eat for better sleep. And it turns about that my endless love for fiber just got some more fuel, because it looks like fiber intake might actually make us sleep better!

The Science on Sleep & Diet

Interestingly, there’s a mutual relationship between sleep and our dietary intake. As I discuss in Go to Bed, there have already been studies that show we can make small changes to our diet in order to promote better sleep. And this relationship is a two-way street: getting better sleep can help us make healthier food choices! Yeah, that’s right. If we’re sleep-deprived, we’re more likely to make poor health choices and succumb to the temptations of highly palatable foods (potato chips, cookies, and the like). While there are fewer of these in a Paleo template, there’s definitely Paleo-friendly treats like dried fruit, nuts, dark chocolate, and grain-free cookies and cakes that can still call our names. When we’re not getting enough sleep, our food choices are less inhibited, meaning we’re more likely to give in to a craving or even eat impulsively. Conversely, getting enough sleep makes it easier to think clearly and make better food choices. For example, people who get more sleep tend to chose more vegetables than people who don’t. But this relationship goes way beyond psychology; there are real, potent relationships between sleep and our physiology as well.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

Since sleep is so dependent on having balanced hormones, it probably doesn’t come as surprising that we would want to eat for hormone balance! Regulating insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol are all fundamental to healthy sleep (read more about hunger hormones in The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin and The Hormones of Hunger). The relationship between sleep and our hunger hormones is pretty clearly delineated in the literature.

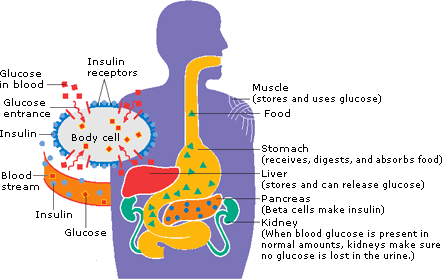

Insulin is the hormone that regulates the amount of sugar in our blood, and leptin is released by our fat cells to send satiety signals (telling our brains that we’re full – something that can pretty easily be offset, as many of us know!). Believe it or not, even short-term changes in sleep patterns can have a huge impact on the balance of these hormones. One study showed that even a single night of partial sleep (4 hours) causes insulin resistance in healthy people. Another study showed that a single night of partial sleep (3 hours, in this case) caused reduced morning cortisol levels (when cortisol should be its highest) and elevated afternoon/evening cortisol levels (when cortisol should be gradually decreasing) as well as elevated morning leptin levels (more on why that’s important below). This means that one night of three or four hours of sleep causes insulin resistance, dysregulated cortisol and increased leptin.

Insulin is the hormone that regulates the amount of sugar in our blood, and leptin is released by our fat cells to send satiety signals (telling our brains that we’re full – something that can pretty easily be offset, as many of us know!). Believe it or not, even short-term changes in sleep patterns can have a huge impact on the balance of these hormones. One study showed that even a single night of partial sleep (4 hours) causes insulin resistance in healthy people. Another study showed that a single night of partial sleep (3 hours, in this case) caused reduced morning cortisol levels (when cortisol should be its highest) and elevated afternoon/evening cortisol levels (when cortisol should be gradually decreasing) as well as elevated morning leptin levels (more on why that’s important below). This means that one night of three or four hours of sleep causes insulin resistance, dysregulated cortisol and increased leptin.

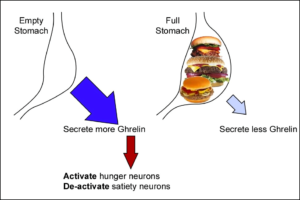

Unlike leptin and insulin, ghrelin is released by the gastrointestinal tract to tell your body that you’re hungry. The mechanism of release is based on the physical status of your stomach. When it’s empty, your stomach releases ghrelin, which talks to the brain in the same way that the other satiety hormones do (in fact, ghrelin even uses the same receptors as leptin!). Once the stomach is full of food, it stops releasing ghrelin, and we realize that we’re satiated. Ghrelin is also related to secretions from the gut (after our food leaves the stomach, it travels through the small intestines and then the large intestines), so certain aspects of our gut health (like our microbiome composition) can make a big difference when it comes to ghrelin secretion. Optimizing ghrelin function (and even using it therapeutically, like an intravenous drug) is actually linked to improving both metabolism and inflammation!

Unlike leptin and insulin, ghrelin is released by the gastrointestinal tract to tell your body that you’re hungry. The mechanism of release is based on the physical status of your stomach. When it’s empty, your stomach releases ghrelin, which talks to the brain in the same way that the other satiety hormones do (in fact, ghrelin even uses the same receptors as leptin!). Once the stomach is full of food, it stops releasing ghrelin, and we realize that we’re satiated. Ghrelin is also related to secretions from the gut (after our food leaves the stomach, it travels through the small intestines and then the large intestines), so certain aspects of our gut health (like our microbiome composition) can make a big difference when it comes to ghrelin secretion. Optimizing ghrelin function (and even using it therapeutically, like an intravenous drug) is actually linked to improving both metabolism and inflammation!

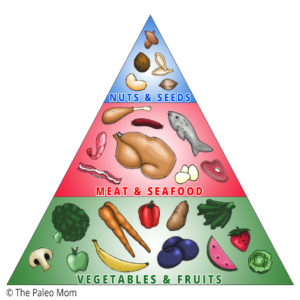

The good news? A strict Paleo protocol that includes three formal meals (instead of “grazing” throughout the day) is one of the best ways to accomplish this without making too many other lifestyle changes. There has also been literature looking more specifically at macronutrient intake. For example, as all of my Go to Bed Challengers know, eating a moderate amount of carbohydrate and making sure to include at least one serving of complex carbohydrates with dinner can help promote melatonin production in the evening.

The good news? A strict Paleo protocol that includes three formal meals (instead of “grazing” throughout the day) is one of the best ways to accomplish this without making too many other lifestyle changes. There has also been literature looking more specifically at macronutrient intake. For example, as all of my Go to Bed Challengers know, eating a moderate amount of carbohydrate and making sure to include at least one serving of complex carbohydrates with dinner can help promote melatonin production in the evening.

Fiber and Sleep — EXCITING NEW SCIENCE!

This new study, published just this past month, is giving us even more information about how our diet directly impacts our sleep. Researchers at Columbia University investigated the eating and sleep behavior of 26 men and women who stayed in the University’s medical center for five days. All of the participants were between the ages of 30 and 45, and they reported sleeping 7-9 hours per night without naps. Participants were excluded if they reported frequent travel (the researchers were trying to avoid people with excessive daytime sleepiness and jetlag), chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, and other concurrent sleep or eating disorders.

Scientists explored whether an ad libitum diet (wherein the participants choose what they eat throughout the day) or a controlled eating diet (wherein the researchers determined exactly what the participants would eat) would affect sleep quality. The ad libitum diet involved the participants eating under a $25 budget per day; participants were instructed to purchase foods “for which the nutrient content was readily available.” For the controlled eating diet, participants were fed prepared food (at Columbia’s Bionutrition Unit) that fit standard macronutrient compositions: 31% of calories from fat, 53% from carbohydrates, and 17% from protein. So, it’s important to keep in mind that neither of these conditions fits a Paleo template; I would say that we generally avoid foods with a label, and we are rarely eating more than half of our calories from carbohydrates. Thus, the main results from the study might have limited validity when it comes to the typical Paleo person. What were they? Overall, they found that participants choosing all their own food made for worse sleep quality when looking at slow wave sleep (deep sleep) and sleep latency (the time it takes to fall asleep). Not that surprising, right?

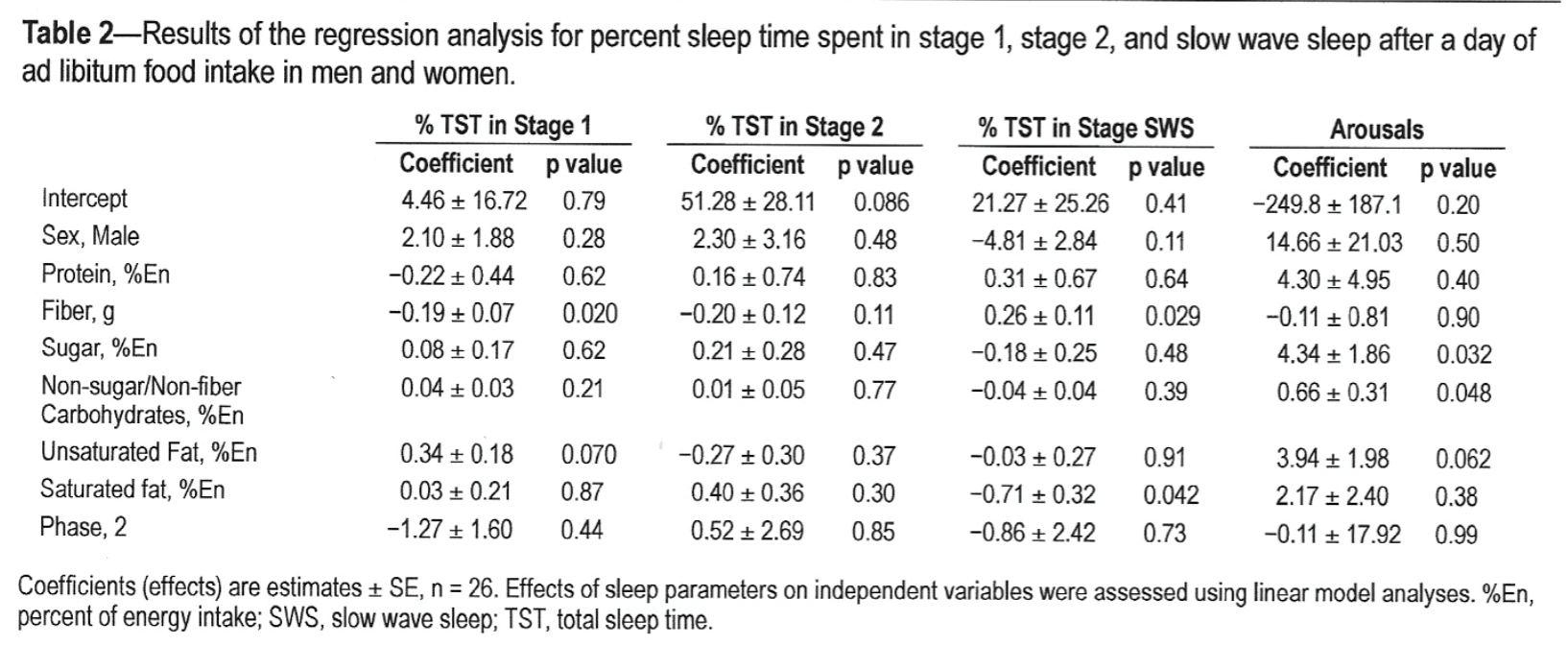

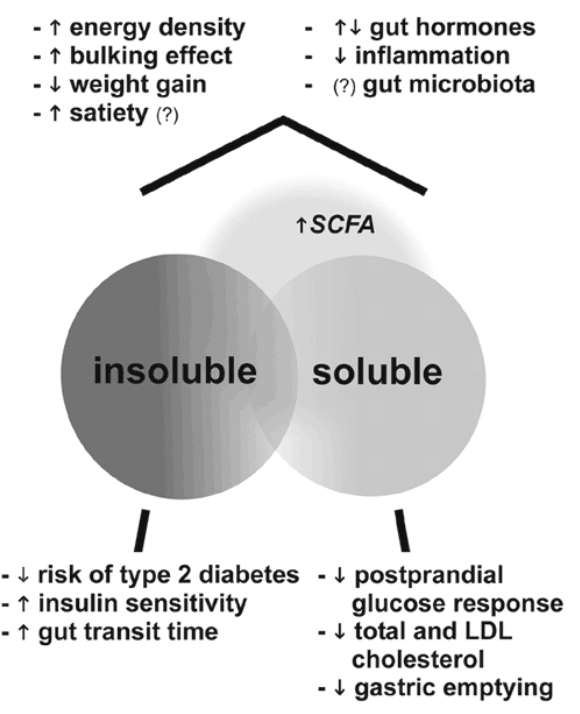

Turning to more specific dietary predictors, the researchers found that increased fiber intake lead to better deep sleep, whereas higher saturated fat intake predicted less deep sleep, and simple carbohydrate (sugars) intake was associated with higher chances of arousals (waking up during sleep). More fiber, less saturated fat and higher protein combined made for a shorter period of time to fall asleep. This is the first paper ever to evaluate how fiber, fat, and protein impact sleep, so this is new insight into the relationship between diet and sleep. Table 2 (from the paper) shows these relationships.

In a lot of ways, these results make sense. I am never shocked when sugar intake is associated with worsened outcomes; across the board, it seems that sugar intake (especially when it’s in the context of processed sugar, like what we likely have here) is hardly ever the “right” choice when it comes to our diet. As far as the “whys” in this case, my guess is that sugar is offsetting the participants’ insulin responses, which in turn can influence cortisol regulation. Considering sugar increased chances of arousals, I wonder if participants were experiencing inappropriate cortisol spikes during the night.

The result I’m most surprised and excited by is the notion that fiber specifically was associated with better sleep. But, when I consider the potential mechanism, it does make sense. There is already a clear relationship between fiber intake and the specific hunger-related hormones I mentioned already. For instance, we know that fiber promotes the suppression of ghrelin, our appetite-stimulating hormone, and reduces absorption of sugar into the bloodstream (thus reducing the general release of insulin as well, which can help with insulin resistance and blood sugar regulation). It’s no secret that I’m a huge proponent of large vegetable consumption and generally recommend that we aim for 10-14 servings of veggies per day (including a variety that hits several different colors, leafy greens, cruciferous veggies, and a few servings of starchy veggies in there too). I genuinely believe that the only way to meet our micronutrient needs is to prioritize vegetable consumption (of course, eating quality meat and seafood is important too!). My Instagram followers are well in tune with my use of #morevegetablesthanavegetarian and #threequartersveggies to describe my meals. This paper does nothing but confirm my love for veggies!

The result I’m most surprised and excited by is the notion that fiber specifically was associated with better sleep. But, when I consider the potential mechanism, it does make sense. There is already a clear relationship between fiber intake and the specific hunger-related hormones I mentioned already. For instance, we know that fiber promotes the suppression of ghrelin, our appetite-stimulating hormone, and reduces absorption of sugar into the bloodstream (thus reducing the general release of insulin as well, which can help with insulin resistance and blood sugar regulation). It’s no secret that I’m a huge proponent of large vegetable consumption and generally recommend that we aim for 10-14 servings of veggies per day (including a variety that hits several different colors, leafy greens, cruciferous veggies, and a few servings of starchy veggies in there too). I genuinely believe that the only way to meet our micronutrient needs is to prioritize vegetable consumption (of course, eating quality meat and seafood is important too!). My Instagram followers are well in tune with my use of #morevegetablesthanavegetarian and #threequartersveggies to describe my meals. This paper does nothing but confirm my love for veggies!

It’s also worth noting that I’ve been reading up about saturated fat lately and have formed some deep concerns about the Paleo movement’s love affair with high-fat diets. Not that I believe low-fat is the way to go either, but there’s a whole range of moderate in between (say 30-40% of caloric intake from fat) that is well supported by the scientific literature to be optimal for a variety of health measures. And we can now add sleep quality to the litany of aspects of health impacted by fat intake (I am working on an upcoming blog post series on this topic, but the takehome message is that even low-carb versions of high-fat diets, meaning over 60% of your calories or more come from fat, are not supported by the scientific literature for safe long-term use).

So, the take-home from this study is really simple and REALLY powerful – so much so that I’m going to be adding more details to my #gotobedchallenge, as I mentioned before. If we want to optimize our sleep, we need to eat more fiber (this might be a catch-all statement for 99.99% of us anyways. Studies show that 25-50g daily is a good goal to optimize the full range of health benefits of this underrated nutrient, and that is well below the average amount consumed in the Standard American Diet), eat less sugar (again, not a shocker, and something that is already incorporated into the 14-Day Go To Bed Challenge), and moderate saturated fat intake.

I am so excited to see where the research goes with this new information, and I’m so excited to include more details in an expanded edition of Go to Bed that released today! And yes, if you’ve already purchased Go To Bed, you will always get access to updates for free. And if you don’t have my epic 280+ page e-book Go to Bed: 14 Easy Steps to Healthier Sleep already, you can head on over here for more details!

Citations

St-onge MP, Roberts A, Shechter A, Choudhury AR. Fiber and Saturated Fat Are Associated with Sleep Arousals and Slow Wave Sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016.

Additional Reading on Fiber

- Fiber Manifesto Part 1

- Fiber Manifesto Part 2

- Fiber Manifesto Part 3

- Fiber Manifesto Part 4

- Fiber Manifesto Part 5

- Resistant Starch

Go To Bed Update NEWS

The reason why I chose to launch Go To Bed as an online program rather than a print book was because sleep research is spiking right now. Every week, there’s two or three new papers, many of which are dramatically altering or adding to our understanding of the relationship between our choices and sleep as well as the relationship between sleep and our health. An online program allows me to update as this new research is published, something I just can’t do with a print book! And, this is an excellent example!

The reason why I chose to launch Go To Bed as an online program rather than a print book was because sleep research is spiking right now. Every week, there’s two or three new papers, many of which are dramatically altering or adding to our understanding of the relationship between our choices and sleep as well as the relationship between sleep and our health. An online program allows me to update as this new research is published, something I just can’t do with a print book! And, this is an excellent example!

Today, a revised version of Go To Bed was released (just in time for the new Group Challenge starting tomorrow night!). If you’ve already bought Go To Bed, you were automatically be e-mailed a link with the new version (to the e-mail address your PayPal account is connected to, please check your SPAM folders!). Remember that you will always get FREE access to any updates or additions to the program! The biggest part of this new update is an expansion of the discussion on diet factors that affect sleep and the addition of a focus on more dietary fiber wrapped up in the 14-Day Go To Bed Challenge, all to reflect the information from this brand-new scientific study. There’s a few other new things too though, including a new section on What To Expect During Your Challenge (which even includes Sleep Score Data Analysis from the first two groups to complete the challenge!) and a new set of tips for getting kids to join in on the challenge!

If you don’t own Go To Bed: 14 Steps to Healthier Sleep yet, it’s an epic 288-page e-book unlike any you’ve ever seen before. You can read more about it to see if you could benefit from its information here.