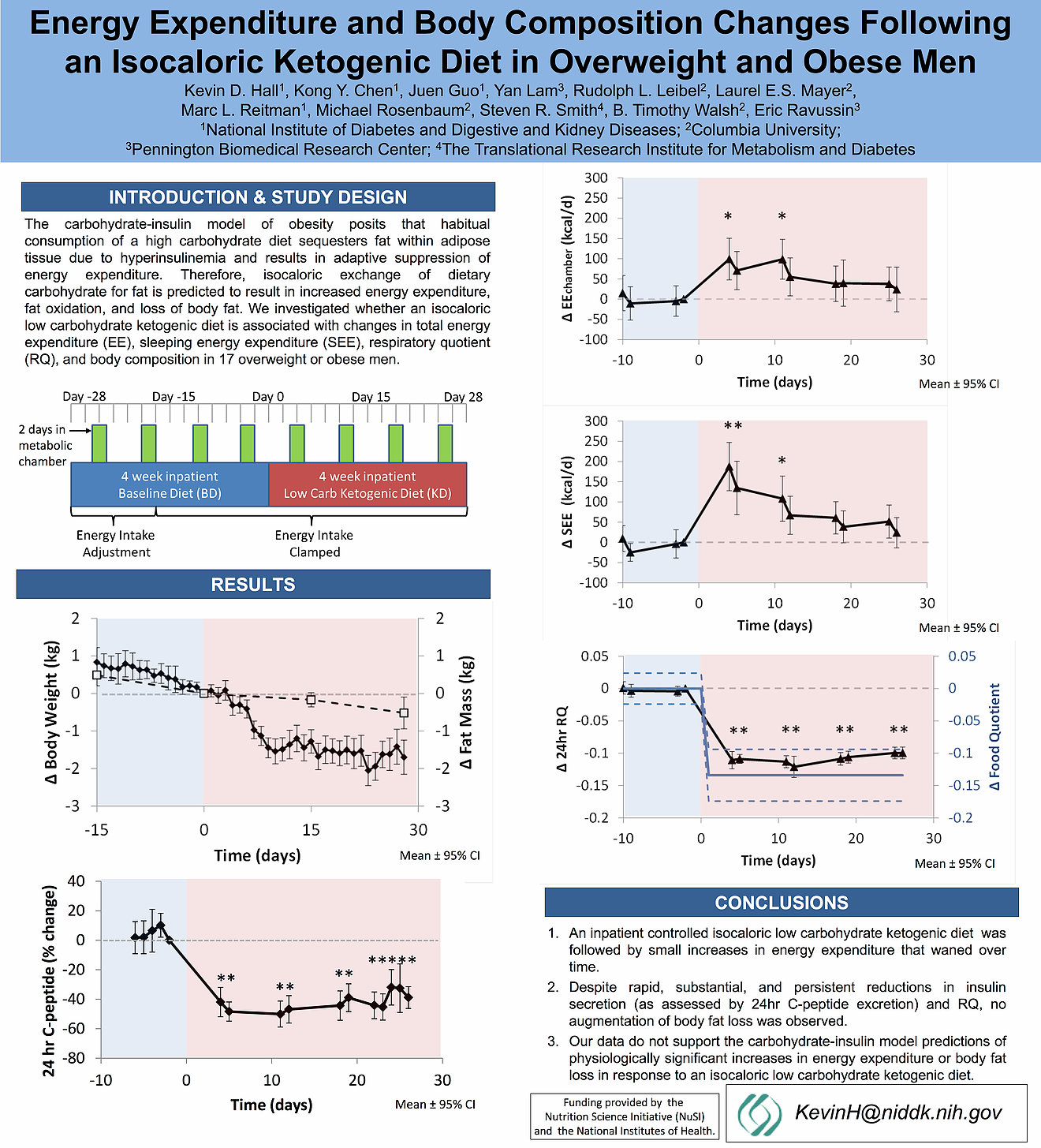

Do low-carb diets have a “metabolic advantage” for weight loss? That’s the million-dollar question! For years, some prominent health figures have proposed that low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets help us burn more body fat even when we eat the same number of calories (or more) as we do on higher-carbohydrate diets. This belief comes partly from the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, which proposes that dietary carbohydrates drive up insulin levels, which in turn leads to greater fat storage. Take away the carbohydrates (and lower the insulin levels), and we’re able to metabolize fat and increase our energy expenditure—so the theory goes!

But, is this really true? Lucky for us, a few recent studies have looked specifically at whether low-carbing causes endocrine adaptations that improve fat loss. The latest one, not yet published but discussed in a poster presentation by lead researcher Kevin Hall (video below and video transcript here), has stirred up quite a bit of controversy.

Hall is quoted as saying that the study falsifies the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis—causing some people to focus on the study’s weaknesses and dismiss its results. So far, criticisms by Dr. Michael Eades, Jason Fung, and David Ludwig have surfaced!

In reality, this is a very important study that does shed light on the “metabolic advantage” issue with low-carbohydrate diets. So, while we wait for the complete study to be published, it’s worth looking at the information we have so far and seeing what we can learn from it!

What Did the Researchers Set Out to Study?

Before we get to the study’s results, this is a really important question to ask, since it helps us understand what the study is really about. Along with the poster presentation provided by Dr. Hall, we can read the trial’s record on ClinicalTrials.gov to see what the researchers were aiming to accomplish. In a nutshell, the study was designed to test whether reducing carbohydrate intake would impact the body’s metabolic regulation, leading to greater energy expenditure and fat loss. The researchers wanted to know if low-carbing (especially on a ketogenic diet) would change the way the body handles calories. The study did not attempt to look at how low-carb diets affect appetite and hunger, or whether or not they are effect long-term strategies for weight loss in general!

How Was the Study Set Up?

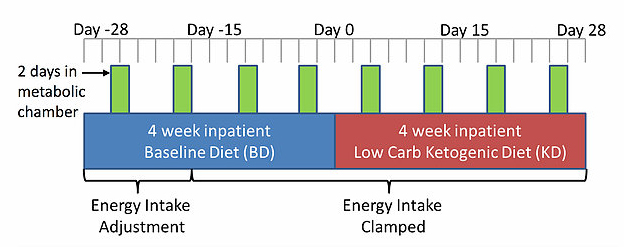

As Dr. Hall explained in his poster presentation, the study involved 17 overweight or obese men undergoing two different diet periods: four weeks on a Standard American Diet (50% carbohydrate with half of that coming from sugar, 15% protein, 35% fat) and four weeks on a ketogenic diet (5% carbohydrate, 15% protein, 80% fat). The participants stayed the entire eight weeks at a clinic, where they received all of their food, had their physical activity monitored, and spend time in a metabolic chamber (two days per week) to measure exact changes in energy expenditure.

During the Standard American Diet phase, participants were supposed to have their calorie intakes measured and adjusted to match what they were burning inside the metabolic chamber (to make the high-carb diet eucaloric, giving people exactly the number of calories they needed for weight maintenance). But, the researchers underestimated how much additional energy people were burning outside the metabolic chambers, leading to a calorie deficit of about 300 calories a day—turning the trial into an unintentional weight-loss study! Although this wasn’t the original plan, it didn’t invalidate the study’s intention, because the participants still consumed an equal number of calories on the higher-carbohydrate diet and on the ketogenic diet (allowing the “metabolic advantage” effect to be tested).

What Did the Study Find?

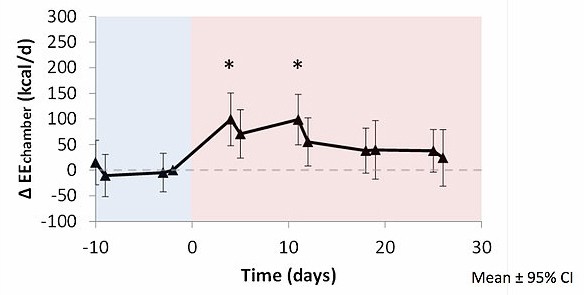

Here’s where it gets interesting! Although the low-carb group initially had a small increase in energy expenditure (EE, about 100 calories a day extra), it disappeared during the next four weeks.

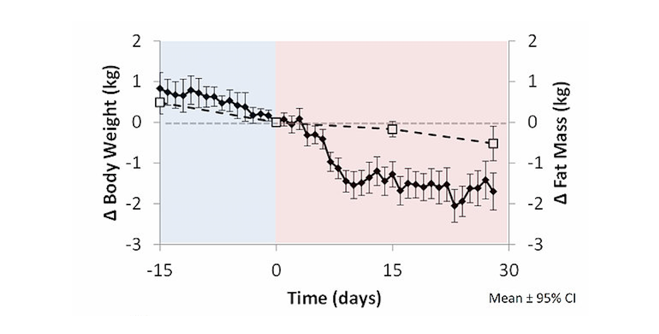

In fact, over the course of the ketogenic diet phase, the rate of fat loss actually slowed down significantly. It ended up taking the ketogenic dieters 28 days to lose as much body fat as they did during 15 days of eating the high-carb diet!

Looking at the poster presentation graphs, we can see that there was indeed a plunge in body weight right after the participants switched to the ketogenic diet. But, as Dr. Hall explains, this weight loss was not from fat, but from water and lean body mass (measured by 24-hour urinary nitrogen excretion). Essentially, people were losing fluid and muscle. That might result in lower numbers on the scale, but it’s not what we want to see if the goal is a healthier body composition!

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

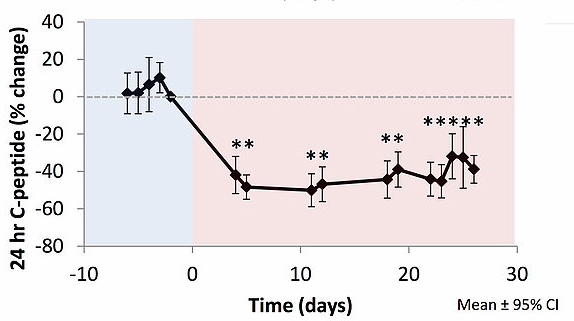

Here’s the other important part: the ketogenic diet was very successful at dropping people’s insulin levels (by 50%!)…

… but that didn’t augment the amount of body fat they were losing, as the “metabolic advantage” theory would predict. There was no correlation between people’s insulin levels and their measured energy expenditure throughout the study. Hall’s poster notes: “Our data do not support the carbohydrate-insulin model predictions of physiologically significant increases in energy expenditure or body fat loss in response to an isocaloric low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet.”

What About the Criticisms?

Despite being impressively designed (and hard to pull off—how many people are willing to spend eight weeks in a clinic and many days locked inside a tiny metabolic chamber?!), the study has received plenty of criticism from different members of the low-carb community. Here are the main points of contention (and the reasons they don’t at all invalidate the study!):

- The study didn’t use a crossover design.

A number of people have pointed out that because the higher-carb diet preceded the ketogenic diet for all of the participants, the keto diet was at a disadvantage (since the greatest weight loss typically happens at the very beginning of a diet and slows down over time). Would the results have been different if the ketogenic diet had come first?

This isn’t a major issue when it comes to testing the hypothesis at hand (the metabolic effects of reducing carbs, independent of calorie intake). We can see that when the participants switched to the ketogenic diet, there was an initial benefit during the adaptation period (the temporary increase in energy expenditure), but that benefit quickly went away. And remember that their total weight loss was higher during the ketogenic diet phase; even though their fat loss was lower (the additional weight lost was lean body mass and water). Actually, this is unintentionally a perfect analogue of many people’s weight loss experiences on keto: you can see how people would believe that keto is better for fat loss when they see a big jump in the number on the scale so soon after switching. After all, most of us don’t track body composition on a day-to-day basis (even though that’s a better metric of health than total weight).

There’s no reason to believe that the higher-carb diet that came first would influence how long the keto benefit lasted, impact the composition of weight loss on keto (water, muscle, or fat), or change the energy expenditure patterns seen with this leg of the study (an initial spike and then movement back towards baseline). In other words, even if the higher-carbohydrate diet benefitted from coming first in terms of an initial weight-loss boost, it shouldn’t affect the more important metabolic measurements during the ketogenic phase.

- The study forced people to eat a fixed amount of calories.

The reason this is supposedly a bad thing is because it prevents us from knowing whether the participants would have spontaneously eaten less on the low-carb diet (due to reduced appetite). But, this is actually a huge plus for this study! By carefully controlling calorie intake, the researchers were able to look solely at metabolic regulation—the subject they set out to examine, since it’s at the crux of the “metabolic advantage” argument for low-carb diets. If the study had allowed an ad libitum food intake, any spontaneous reduction in calories would have made it impossible to tell whether fat loss was due to metabolic changes or just reduced energy intake.

Let’s be clear: saying that a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet does not provide any kind of metabolic advantage is different than saying you can’t lose weight with this approach. What it does say is that any weight lost is credited to reduced appetite and therefore reduced caloric intake. This is also likely why tens of thousands of people have had weight loss success with Paleo: by focusing on the most satiating foods and nutrient-density (nutrient deficiencies can cause cravings), overweight individuals tend to achieve a mild caloric deficit without additional effort.

- The study didn’t last long enough.

A month eating a ketogenic diet should definitely be long enough to experience “fat adaptation,” and this is confirmed by the study results! As Dr. Hall explains, all of the adaptation occurred within the first week of switching to the ketogenic diet, with no additional changes occurring after that. There’s no reason to believe the results would change significantly if the participants were studied over a longer period of time. Plus, getting people to voluntarily confine themselves to a clinic and metabolic ward chambers for eight weeks is challenging enough; a longer study of this type might not be realistic.

As a matter of fact, this study actually is a longer version of a previous trial by Dr. Hall, et al., called “Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity.” That study looked 19 obese adults who spent two separate periods in a metabolic ward, eating reduced calorie diets that were either low in fat (7.7% of calories) or relatively low in carbohydrate (29% of calories) for six days each. The results showed that cutting fat resulted in more body fat loss than cutting carbohydrates, even though the low-fat diet didn’t reduce people’s insulin levels. But, this study was criticized for being too short to get people “fat adapted.” So, this newer study already aimed to address the length concern!

What Does it Mean For Us?

This study casts major doubt on the idea that low-carbing helps magically melt away more body fat (without needing us to eat fewer calories) through specific effects on fat regulation. Despite the number of times this claim is made in the health world (this article by examine.com is a great quick summary), there just isn’t any scientific evidence to support it! And, given what we know about how certain higher carbohydrate, fiber-rich plant foods can support our gut microbiome (by feeding our beneficial bacteria some resistant starch, fermentable fibers, and other prebiotics), the idea of totally cutting carbs out of our diet seems both unnecessary for weight loss and a genuinely bad idea for overall health. Having more balanced macronutrient ratios is the best way to go to keep our bodies nourished, our hormonal systems regulated, and our gut flora happy!

Certainly food quality matters for health beyond the issue of weight loss: micronutrient sufficiency is a requirement of every healthy diet. But, when it comes to wanting to lose weight, calories do matter. And, while calories in versus calories out should not be the only criteria for food choices, this study supports the idea that energy balance is the most important dietary determinant for weight loss.

Of course, there’s still a possibility that low-carbohydrate diets have an advantage in terms of satiation (making people feel full on fewer calories). That’s another topic entirely—one this study didn’t aim to address. But when it comes to a “metabolic advantage,” the evidence just isn’t there. For now, we should await the full results of this study before dismissing its findings, criticizing its researchers, or becoming defensive. After all, science is about the search for truth—not the search for things that support what we want to be true!

Citations

Hall KD, et al. “Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity.” Cell Metab. 2015:22;427-436.

Dr. Hall’s Poster: