Finding health via diet and lifestyle changes can make us feel superhuman—but, we’re not (sadly). While we may lose weight, get fit, and mitigate chronic illnesses, calamities can and do still happen.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

A slip of the kitchen knife, a tumble on the bike, or an emergency surgery could be all it takes to land you on the long and winding road towards wound healing. As anyone who’s suffered serious tissue trauma knows, the recovery process can be frustratingly slow and utterly inconvenient—not to mention really, really painful. Yet while there’s no way to totally fast-forward through the aftermath of injury, there are ways to expedite the healing process and reduce your recovery time as much as possible.

How? When you get wounded, your body goes into a resource-guzzling state of emergency—rapidly calling upon your supply of vitamins, minerals, and amino acids in an effort to repair the damage. That means your ability to heal depends largely on the quality of your diet, both before and after your injury occurs. As a result, it’s important to not only maintain a nutrient-dense diet that supports immunity and repair (like a Paleo diet that includes organ meat, seafood, and lots of veggies), but also boost your intake of some key nutrients in the days, weeks, months, and even years following your injury.

What Happens When You Get Wounded?

When you get hurt, your only conscious thought might be “OW!” (or perhaps a less family-friendly exclamation)—but by the time the pain even registers, your body is already hard at work launching an intricate four-phase repair process.

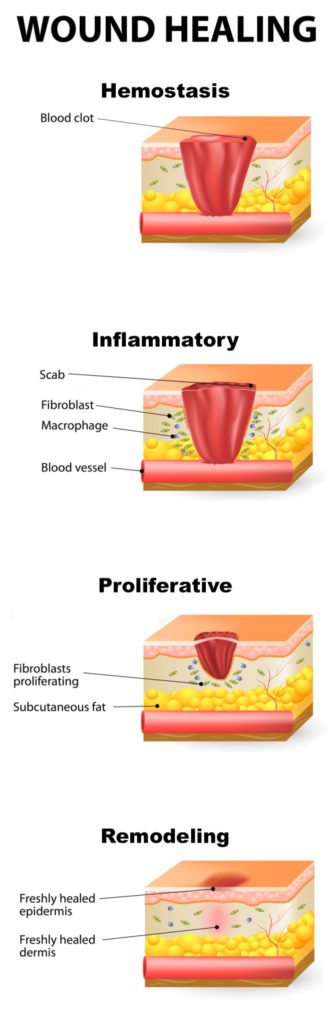

When an injury penetrates deep enough to damage your dermis, the inner layer of your skin, your body’s first priority is to stop any bleeding—as well as clamp shut the newly made doorway between the pathogen-filled outer world and your ultra-vulnerable innards. Within a few minutes, platelets in your blood start sticking to the site of injury and binding together, which is called the hemostasis phase of wound healing (better known as blood clotting).

When an injury penetrates deep enough to damage your dermis, the inner layer of your skin, your body’s first priority is to stop any bleeding—as well as clamp shut the newly made doorway between the pathogen-filled outer world and your ultra-vulnerable innards. Within a few minutes, platelets in your blood start sticking to the site of injury and binding together, which is called the hemostasis phase of wound healing (better known as blood clotting).

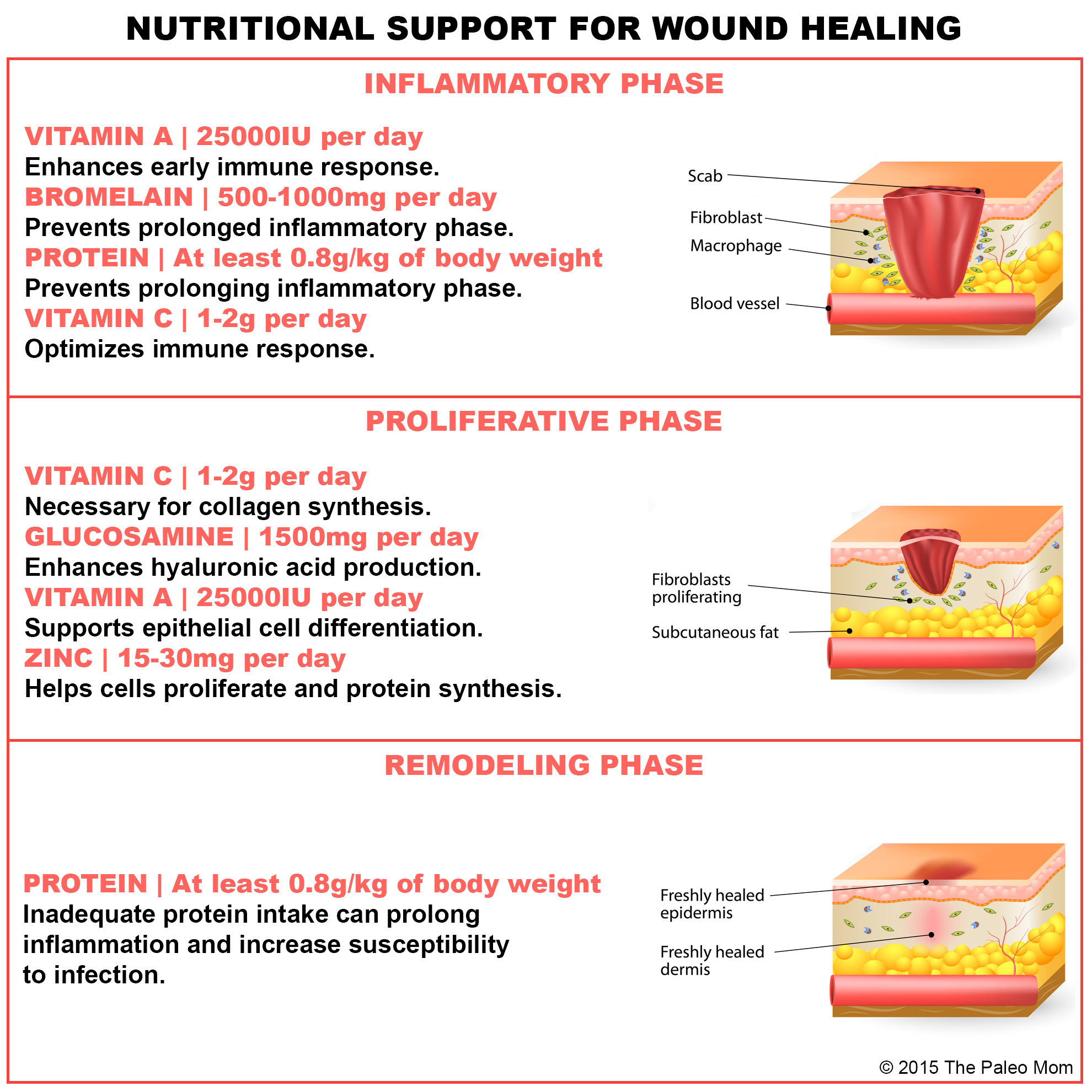

With the wound’s broken blood vessels now plugged up, your body unleashes its molecular cleanup crew, clearing out dead tissue, bacteria, and any foreign material that found its way into the injury site. White blood cells start gobbling up debris in a process called phagocytosis, and blood vessels dilate in order to let important antibodies, growth factors, nutrients, and enzymes reach the wound. This is called the inflammatory phase of wound healing—and as you might guess by that name, it’s accompanied by some less-than-delightful pain, swelling, redness, and difficulty using the injured body part.

Next, it’s time to start rebuilding the wound’s lost or damaged tissue. New capillaries form and fibroblasts rush to the scene, secreting collagen and other substances to help form new connective tissue. Myofibroblasts help shrink the wound by gripping the edges of the injured area and contracting—leading to the tight, itchy feeling you’ve probably experienced as a wound starts to heal. This is the proliferative phase of wound healing.

Last comes the remodeling or maturation phase—where collagen fibers get reorganized, any cells that are no longer needed die off, and healing is complete. This phase can happen weeks, months, or even years after the injury occurred. Think of how a scar may be red and bumpy early on after healing, but slowly smooth out, fade to white, and maybe even disappear altogether over time.

Basically, while you’re cursing and ransacking the drawers for band-aids and Neosporin (or if things are really serious, high-tailing it to the ER), your body is dutifully carrying out a cascade of highly-regulated processes to regenerate and heal you. Pretty great, huh?

Here’s where having a nice, full reservoir of micronutrients and amino acids comes in handy. Even if your diet is already dialed in and you’re regularly feeding your body nutrient-dense foods, the increased cellular activity and metabolic demands that happens during these wound healing phases means you’ll be burning up resources even faster than usual. And that means now is the time to boost your diet with wound-supportive nutrition.

But what exactly does that entail? In order to orchestrate its complex healing process, your body needs a vast array of nutrients, but also relies on the key nutritional players of vitamin A, vitamin C, zinc, dietary protein, arginine, glutamine, and bromelain. It’s an extra focus on these key players that supports and can even help speed healing.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Key Players for Healing

Vitamin A. You might already know that vitamin A is a micronutrient superstar, but when it comes to wound healing, its role is particularly vital. Vitamin A, or more specifically the animal form of vitamin A called retinoic acid, is necessary for immune function, cell differentiation, and epithelial formation—all of which kick into high gear after tissue injury. During the inflammation phase of healing, vitamin A helps boost immunity to fight off pathogens that can infiltrate a fresh wound. During the proliferative phase, your body also uses vitamin A to help epithelial cells differentiate (in other words, turn from generic cells into specialized cells) and increases the amount of collagen that gets deposited in the wound site.

So where can you point your fork in order to load up on vitamin A? The richest sources of true vitamin A—in the form of retinol—are animal foods: liver, egg yolks, cod liver oil, and full-fat dairy products. Good sources of beta-carotene, a vitamin A precursor, include carrots, dark leafy greens, squashes, and melons, but absorption and conversion to vitamin A tends to be very low (and almost nonexistent for some people). Existing studies of vitamin A supplementation suggest that levels of 10,0000 to 50,000 IU per day may be beneficial (for example, see Douglas Labs Vitamin A, a modest dose which is derived from fish oil). Note however that vitamin A toxicity can be a concern (especially over 50,000IU daily), especially if you’re vitamin D deficient or pregnant (another reason why whole food sources rock: they contain vitamin D too).

Vitamin C. Along with acting as an important antioxidant, vitamin C plays a role in every stage of the healing process—and inadequate intake can thwart your body’s efforts to recover. Vitamin C helps synthesize collagen, optimize immune response, and usher monocytes to injured tissue, where they transform into macrophages and gobble up foreign (and potentially harmful) debris. Great sources of this vitamin include citrus fruits, tomatoes, broccoli, cauliflower, sweet peppers, dark leafy greens, cantaloupe, and papaya. To supercharge your vitamin C intake while healing, Douglas Labs offers a high-quality corn-free, yeast-free, wheat-free, dairy-free, soy-free powdered supplement (so you can dial in a dose that doesn’t give you gastrointestinal symptoms). Doses of up to 200 mg per day appear helpful for wound healing if your previous intake was too low, and in the case of severe or complex wounds, amounts of 1,000 to 2,000 mg per day may be beneficial. (Be aware, though, that extremely high doses of vitamin C might be a problem if you’re inclined to form kidney stones).

Zinc. Because of its role as a cofactor in a number of enzyme reactions, including ones involved in synthesizing protein, zinc plays a major part in helping cells proliferate—as well as closing wounds and facilitating the inflammatory process. Despite this, when it comes to healing, the best approach to zinc isn’t always “the more, the merrier”: most studies show that an extra-high zinc intake only expedites the healing process if you were deficient to begin with. Of course, only 27% of Americans meet the daily recommended intake of zinc, making it one of the most common mineral deficiencies (you can easily test whether or not you’re deficient using the Designs For Health Zinc Challenge Liquid, although note, this test isn’t particularly accurate if you’re only a little deficient). The best plan of attack? Fill your diet with a steady supply of zinc-rich foods—including oysters, clams, pumpkin seeds, red meat, liver, crab, and lobster. If your pre-injury diet was low in these items, consider taking a supplement (such as Douglas Labs Zinc Picolinate, one of the most absorbable forms of zinc) or treating yourself to extra oysters, which boast the highest zinc concentration of any food. To enhance wound healing, aim for a zinc intake of up to 40 mg (or 176 mg in the form of zinc sulfate) for ten days (careful with long-term supplementation since zinc toxicity is not fun).

Dietary protein. During wound healing, getting plenty of protein is crucial for keeping your body’s repair processes running smoothly, since protein is involved in virtually every stage of the healing process. Under normal circumstances, the average adult uses up about 60 to 70 grams of protein each day as a minimum—but after severe injury, that number can jump as high as 150 to 250 grams. Your body’s immune cells—including monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, leukocytes, and phagocytes—are made up mostly of protein, so a steady supply is especially important for the early stages of wound healing, when your inner army is fighting off foreign invaders and attempting to clean up the scene of the crime (err, injury). As a result, not eating enough protein can prolong the inflammation phase and increase your susceptibility to infection. Excellent sources of protein while you’re in recovery mode include seafood (most digestible protein!), meats of all kinds, poultry, and eggs. It seems a bit silly to recommend any particular supplement for dietary protein, but this seems like a good time to mention the desiccated organ meat supplements from Dr. Ron’s. It’s a very painless way to increase organ meat consumption and dietary protein!

Amino acids. Along with overall protein intake, certain amino acids—the building blocks of protein—play specific, important roles in wound recovery:

- Arginine. Arginine’s time to shine is during the first two phases of healing, where it assists in immune function and collagen growth. Studies in humans have shown that arginine supplementation significantly enhances the amount of collagen deposited into a wound site, along with boosting immune cell production. Foods high in arginine include seafood (particularly crustaceans like crab, shrimp, and lobster), nuts (particularly almonds, walnuts, hazelnuts, and Brazil nuts), spinach, watercress, poultry, and pork. If you want to go the supplement route, NOW Foods L-Arginine Powder is a good choice; studies showing a benefit of arginine supplements for healing have used between 17 and 30 grams per day.

- Glutamine. As with arginine, tissue levels of glutamine appear to influence wound repair and immune function. This amino acid is the most abundant one in your bloodstream, and the many “hats” it wears include acting as the primary nutrient and energy source for immune cells, assisting in cell growth, and serving as a protective antioxidant. To boost your glutamine intake naturally, focus on bone broth (or simply add Bone Broth Protein to your coffee, tea, smoothie, etc.), poultry, seafood, and high-protein cuts of meat. Although there are no concrete guidelines for optimal glutamine supplementation during wound healing, the suggested dose for adults is 0.57 grams per kilogram of bodyweight (studies using L-glutamine for gut barrier health use doses around 30-50g per day, which is in the same range). NOW Foods L-Glutamine Powder is what’s in my cupboard.

Bromelain. Along with the all-star lineup of nutrients and amino acids listed above, a particular family of enzymes—called bromelain—has a long track record for supporting wound healing. Derived from pineapple and other related plants, bromelain has been shown to reduce bruising, swelling, pain, and healing time after trauma and surgery. It’s even been shown to have analgesic properties, lower risk of cancer, and mitigate osteoarthritis! The best source—apart from gnawing on pineapple stems—is from supplements such as Douglas Labs Bromelain-5000 Capsules, in amounts of at least 500 to 1,000 mg daily following injury or surgery. Note that the scientific research has yet to reach a firm guideline for ideal dose of bromelain. Also, supplement companies use a variety of units in their labeling, which can make choosing the right supplement confusing. The Douglas Labs brand above is definitely on the high end of dose supported by research, but also contains no allergenic ingredients.

Takehome Message:

While there’s no magic bullet to spare you the swollen, achey, bloody aftermath of an injury, loading your diet with wound-supportive nutrients can do wonders for the healing process and return you to a state of health as rapidly as possible.

You’ll notice a common theme in the above-mentioned nutrients: they tend to be richly found in organ meat, seafood, and dark green veggies. Certainly, additional supplementation, or choosing specific nutrient-dense foods for their wound-healing nutrients, can help the healing process—but, the best thing you can do to help yourself heal is be nutrient-sufficient in all of the essential nutrients (and the non-essential ones too) before you get injured. So, go grab some oysters, some kale, some liver and some pineapple! Er, well, maybe not necessarily all at once.

Citations:

Barbul A, et al, Arginine enhances wound healing and lymphocyte immune responses in humans. Surgery. 1990 Aug;108(2):331-6; discussion 336-7.

Casey G. Nutritional support in wound healing. Nurs Stand. 2003 Feb 19-25;17(23):55-8.

Casaer MP and Ziegler TR. Nutritional support in critical illness and recovery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Jun 10. pii: S2213-8587(15)00222-3. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00222-3. [Epub ahead of print]

Collins N. Glutamine and wound healing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002 Sep-Oct;15(5):233-4.

Cordain L et al, Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):341-54

Gruner T and Arthur R. The accuracy of the Zinc Taste Test method. J Altern Complement Med. 2012 Jun;18(6):541-50. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0298.

Lin Y, et al. Variability of the conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A in women measured by using a double-tracer study design. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jun;71(6):1545-54.

MacKay D and Miller AL. Nutritional support for wound healing. Altern Med Rev. 2003 Nov;8(4):359-77.

Majid OW and Al-Mashhadani BA. Perioperative bromelain reduces pain and swelling and improves quality of life measures after mandibular third molar surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement Med. 2012 Jun;18(6):541-50. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0298.

Stechmiller JK. Understanding the role of nutrition and wound healing. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010 Feb;25(1):61-8. doi: 10.1177/0884533609358997.

Wild T, et al. Basics in nutrition and wound healing. Nutrition. 2010 Sep;26(9):862-6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.05.008.