Olive oil is one of the oldest (and most revered!) edible oils out there, with culinary uses dating back to at least 1000 BC, and other uses scrolling back even further (such as anointing priests and kings). Not to mention, it’s versatile and delicious (olive oil ice cream, anyone?). Combined with mounting research suggesting olive oil is cardioprotective, it’s no wonder that this is one of the least controversial fats out there—given the green light by the Paleo community, vegans, vegetarians, low-carbers, the Harvard School of Public Health, and even the USDA. Not many foods can claim such widespread acceptance!

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

But, there is one area of ongoing debate when it comes to olive oil: cooking. Because it’s composed of mostly unsaturated fat (which is less chemically stable than saturated fat), many voices in the health community are claiming olive oil can become damaged when heated and lose its famed health benefits. In fact, some of the more extreme claims are that heated olive oil becomes legitimately toxic and can contribute to heart disease and cancer.

But, there is one area of ongoing debate when it comes to olive oil: cooking. Because it’s composed of mostly unsaturated fat (which is less chemically stable than saturated fat), many voices in the health community are claiming olive oil can become damaged when heated and lose its famed health benefits. In fact, some of the more extreme claims are that heated olive oil becomes legitimately toxic and can contribute to heart disease and cancer.

So, should we reserve olive oil for cold dishes only and nix it for cooking? As always, let’s look past the gossip and go straight to the science to find out!

What’s the Problem?

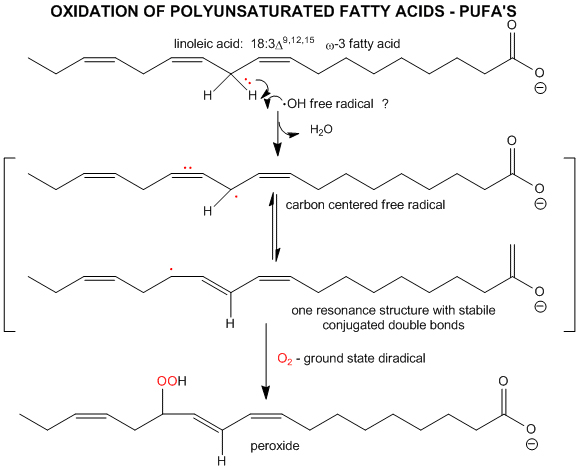

Along with its high monounsaturated fat content, olive oil contains 1.4g of polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) per tablespoon (mostly in the form of linoleic acid), which is about 10% of its total fat content. Like all polyunsaturated fats, linoleic acid has multiple double bonds that are vulnerable to oxidation, especially when exposed to high temperatures (hello, fried foods!). Likewise, monounsaturated fat contains a single double bond, which makes it less heat-stable than saturated fats (though a definite step up from PUFAs) on the oxidation front.

So, in theory, we might expect olive oil to get pretty damaged when we expose it to heat on the stove. And with some reports of an olive oil smoke point as low as 250F, this would seem to provide corroborating evidence that olive oil should never be heated. The molecular damage from heating olive oil would erase many (if not all) of its beneficial properties and even make it somewhat hazardous to consume (since oxidized lipids in your diet can contribute to oxidized lipids in your blood—a big factor in heart disease). Scary, right?

Luckily for olive oil fans, the science shows something quite different!

What the Research Shows

A number of studies have been conducted on olive oil to assess the effects of cooking on its structure and nutritional content, as well as what happens in humans after olive oil is ingested.

Across the board, the research shows that even with a fair amount of heat exposure, extra virgin olive oil resists oxidation better than many other cooking oils. In one study, it took over 24 hours (a day straight!) of frying before olive oil generated enough polar compounds to be considered harmful. In another study, even after 36 hours of cooking, olive oil had retained most of its beneficial vitamin E content.

Across the board, the research shows that even with a fair amount of heat exposure, extra virgin olive oil resists oxidation better than many other cooking oils. In one study, it took over 24 hours (a day straight!) of frying before olive oil generated enough polar compounds to be considered harmful. In another study, even after 36 hours of cooking, olive oil had retained most of its beneficial vitamin E content.

In fact, high quality (low acidity) extra virgin olive oil can have a smoke point as high as 410F. That’s higher than most cooking applications and makes olive oil (at least, the good stuff) more heat stable than many of our other go-to cooking fats!

The magic words here, though, are “extra virgin”: refined olive oils start to degrade in heat faster than their unrefined counterparts, and are overall more susceptible to oxidation (those are the ones with the low smoke point). The reason is due to extra virgin olive oil’s high content of antioxidants that protect the oil from damage in the face of heat or other oxidants. High-quality olive oils are very rich in at least 30 phenolic compounds with antioxidant activity—particularly oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol—as well as alpha-tocopherol, an important form of vitamin E. And, it turns out that olive oil’s phenolic acid content helps stabilize vitamin E in the presence of heat, explaining why even sustained cooking times don’t obliterate the oil’s nutritional value. (For more info on important phytochemicals like phenols, you can read my recent post here).

In fact, those same beneficial compounds that protect olive oil from oxidation also help protect human LDL particles from damage. A number of trials have shown that after consuming olive oil, LDL from people’s serum takes longer to oxidize and is more resistant to oxidation, suggesting a major benefit for heart disease risk. So, whatever potential harm could come from olive oil’s relatively less-stable structure (compared to saturated fats like ghee and coconut oil), it appears to be more than compensated by its awesome phytonutrient content!

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Getting the Most Out of Your Olive Oil

In order to get olive oil’s powerful antioxidant properties (and therefore avoid some of the hazards of its more delicate chemical structure), quality is key! And unfortunately, obtaining high-quality olive oil isn’t always straightforward. Even brands labeled “extra virgin” can vary wildly in freshness, phenol content, and linoleic acid level, and the olive oil industry is notorious for deceptive labeling (the book Extra Virginity by Tom Mueller chronicles the whole saga).

So, how do you choose the best oil? A few simple tips can help:

- Look for brands that list a harvest date on the bottle, which will tell you when the olives themselves were picked. The more recent the date, the better (no more than 12 – 18 months)!

- Always choose oils in dark glass bottles—never plastic or clear ones.

- Oils that were imported from other countries are more likely to be deceptively labeled (and even cut with non-olive vegetable oils—yikes!), so look for more local oils, especially ones from California, or domestic companies that are transparent with their Mediterranean sources and production practices.

- When tasting the oil, it should be pungent and peppery, even stinging the back of your throat a bit—that’s a sign of a high polyphenol content. Yes, I regularly sample olive oils to test for that peppery bite!

- Make sure the label says “extra virgin” and not “refined.”

- Fresher is better. Unlike vinegars or wines, olive oil does not get better with age.

Equally important is taking care of your olive oil so that it doesn’t oxidize before you even get to use it! For best results, store your olive oil in a cool, dark place away from light and heat (e.g., in the pantry instead of on the counter next to the stove). Even high-quality, properly stored olive oils can start to degrade after four to six months, so purchase your oils in smaller bottles to make sure you finish each one up while it’s still fresh. And, even though olive oil may be relatively stable when heated, keep in mind that any fat will eventually get damaged from high temperatures (and that high-temperature cooking can destroy some nutrients in the other ingredients you’re using)—so limit frying in favor of gentler cooking methods, like sautéing.

So there you have it! As long as your olive oil is fresh and rich in phenols, you can enjoy it as a cooking oil without worry!

Citations

Allouche Y. “How heating affects extra virgin olive oil quality indexes and chemical composition.” J Agric Food Chem. 2007 Nov 14;55(23):9646-54.

Casal S, et al. “Olive oil stability under deep-frying conditions.” Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 Oct;48(10):2972-9.

Covas MI, et al. “The effect of polyphenols in olive oil on heart disease risk factors: a randomized trial.” Ann Intern Med. 2006 Sep 5;145(5):333-41.

Marrugat J. “Effects of differing phenolic content in dietary olive oils on lipids and LDL oxidation–a randomized controlled trial.” Eur J Nutr. 2004 Jun;43(3):140-7.

Pellegrini N. “Direct analysis of total antioxidant activity of olive oil and studies on the influence of heating.” J Agric Food Chem. 2001 May;49(5):2532-8.

Prabhu HR. “Lipid peroxidation in culinary oils subjected to thermal stress.” Indian J Clin Biochem. 2000 Aug;15(1):1-5.

Ramirez-Tortosa CM. “Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Increases the Resistance of LDL to Oxidation More than Refined Olive Oil in Free-Living Men with Peripheral Vascular Disease.” J. Nutr. December 1, 1999 vol. 129 no. 12, 2177-2183.

Staprãns I, et al. “Oxidized lipids in the diet are a source of oxidized lipid in chylomicrons of human serum.” Arterioscler Thromb. 1994 Dec;14(12):1900-5.

Tuck KL & Hayball PJ. “Major phenolic compounds in olive oil: metabolism and health effects.” J Nutr Biochem. 2002 Nov;13(11):636-644.

Visioli F. “Rusting the pipes: ingestion of oxidized lipids and vascular disease.” Vascul Pharmacol. 2014 Jul;62(1):47-8.