Is Paleo safe for kids? Absolutely! In fact, children might benefit from Paleo even more than adults because their food habits and associations are just starting to form, and the nutrient density of the Paleo diet readily supports the demands of growth and development. A diet rich in colorful fruits and vegetables provides a wide spectrum of vitamins and minerals for a healthy body and immune system, and a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids is crucial for brain development. Plus, gluten and the other lectins in grains and legumes can be even more damaging to a child’s immature digestive tract than to an adult’s mature one, so minimizing their presence in a child’s diet can go a long way toward supporting gut health from an early age.

That being said, making sure children get all the nutrients they need is important with any dietary framework, and Paleo is no exception (see also The Importance of Nutrient Density).

Micronutrient Requirements for Young Children

Micronutrient Requirements for Young Children

Due to their faster rate of growth and higher metabolism, children have greater micronutrient needs relative to their total body weight than adults do. This makes it very important to emphasize the most nutrient-dense foods, like organ meats, seafood, healthy fat sources, and vegetables, and limit “empty calories,” which take up volume in a child’s stomach without contributing to daily nutritional needs. A few micronutrients are particularly critical due to the specific developmental processes that children are going through, including the following:

- Vitamin A is important for healthy vision, immunity, and gene expression (vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of childhood blindness in developing nations and puts children at significantly increased risk of infection). The best sources of vitamin A in the form of retinol are liver, eggs, and full-fat dairy, and the best sources of vitamin A precursors are sweet potatoes, leafy green vegetables, squash, carrots, and many other orange and green fruits and vegetables.

- Vitamin B12 is used in many metabolic processes and is important for neurological health, including playing a role in myelination from early fetal development all the way through early adulthood. The best sources of B12 are animal products like red meat, fish, shellfish, poultry, and eggs.

- Vitamin C plays a role in synthesizing collagen and neurotransmitters during childhood and beyond. It’s also critical for proper immune function, helping children fight off infections as they’re exposed to new pathogens. The best sources of vitamin C are citrus fruits, melons, berries, kiwis, papayas, mangoes, and pineapple.

- Vitamin D supports growing bones and teeth through its role in facilitating calcium metabolism (vitamin D deficiency is a major cause of rickets, which occurs when bones fail to mineralize and results in bowed legs and arms). The best sources of naturally occurring vitamin D (apart from what the body produces during sun exposure) are fatty fish, liver, eggs, and full-fat dairy.

- Calcium is used to build bones and teeth. An adequate intake during childhood and adolescence is necessary to attain strong peak bone mass and reduce the risk of osteoporosis later in life. Make sure to include plenty of calcium-rich foods, see The Paleo Diet for Skeletal Health and Why Don’t I Need to Worry About Calcium?

- Iodine is needed for brain development in infancy, is used to synthesize thyroid hormones, and helps control a number of bodily processes, such as growth, metabolism, and development. Because some Paleo diets omit iodized salt and processed foods made with iodized salt—the most common sources of iodine in the modern diet—dietary sources of iodine are extremely important for young children: sea vegetables, fish, eggs, and dairy.

- Zinc plays a role in growth, development, neurological function, immune function, and cell metabolism. Zinc deficiency can impair a child’s physical growth and increase the susceptibility to infection, so adequate intake is important for preventing “failure to thrive.” The best sources of zinc are organ meat, shellfish, nuts, and seeds.

- Omega-3 fats are critical for healthy brain development, vision, gene expression, nervous system function, and building cell membranes. The best sources are fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, and sardines, as well as walnuts.

Essential Vitamin and Mineral Requirements for Young Children

Essential Vitamin and Mineral Requirements for Young Children

Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) are established for a variety of demographic groups by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine. Remember that an RDA is the dietary intake level of a specific nutrient considered sufficient to meet the needs of 97.5 percent of healthy individuals, implying that this intake would be harmfully inadequate for just 2.5 percent of the healthy population. RDAs are calculated based on the estimated average requirement for each nutrient, something that some specialists believe is an underestimation of our true biological need, as these levels are generally determined based on symptoms of deficiency rather than amounts needed for optimal health.

The following are the established RDAs for essential vitamins and minerals for babies and toddlers.

| RDA for Ages 0–6 Months | RDA for Ages 7–12 Months | RDA for Ages 1–3 Years | |

| Vitamin A | 375 mcg RE | 375 mcg RE | 300 mcg RE |

| Vitamin B1 (thiamin) | 0.3 mg | 0.4 mg | 0.5 mg |

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) | 0.4 mg | 0.5 mg | 0.5 mg |

| Vitamin B3 (niacin) | 5 mg | 6 mg | 6 mg |

| Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) | 2 mg | 3 mg | 2 mg |

| Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) | 0.3 mg | 0.6 mg | 0.5 mg |

| Vitamin B9 (folate) | 25 mcg | 35 mcg | 150 mcg |

| Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) | 0.3 mcg | 0.5 mcg | 0.9 mcg |

| Vitamin C | 30 mg | 35 mg | 15 mg |

| Vitamin D | 7.5 mcg | 10 mcg | 15 mcg |

| Vitamin E | 3 mg TE | 4 mg TE | 6 mg TE |

| Vitamin K | 5 mcg | 10 mcg | 30 mcg |

| Calcium | 400 mg | 600 mg | 700 mg |

| Copper | 600 mcg | 700 mcg | 340 mcg |

| Iodine | 40 mcg | 50 mcg | 90 mcg |

| Iron | 6 mg | 10 mg | 7 mg |

| Magnesium | 40 mg | 60 mg | 80 mg |

| Manganese | 0.6 mg | 1 mg | 1.2 mg |

| Phosphorus | 300 mg | 500 mg | 460 mg |

| Selenium | 10 mcg | 15 mcg | 20 mcg |

| Zinc | 5 mg | 5 mg | 3 mg |

g = milligrams, mcg = micrograms, RE = Retinol Equivalents, TE = Tocopherol Equivalents

Macronutrient Requirements for Children

When it comes to macronutrient ratios for kids, we can get a clear idea of how they should eat by looking at the composition of human breast milk. In prehistoric cultures, children likely received at least some breast milk until age 4 or 5, so it’s a pretty safe bet that the macronutrient ratio of breast milk is a good guide for kids up to that age. Mother’s milk is considered the perfect food for a growing young child, and we can continue to use the macronutrient ratio of breast milk as a general guide for children’s diets for as long as they are growing; after all, the macronutrient ratio of breast milk is often used as a guide for carbohydrate consumption for adults! (See also The Best Dairy Choice for Growing Children).

When it comes to macronutrient ratios for kids, we can get a clear idea of how they should eat by looking at the composition of human breast milk. In prehistoric cultures, children likely received at least some breast milk until age 4 or 5, so it’s a pretty safe bet that the macronutrient ratio of breast milk is a good guide for kids up to that age. Mother’s milk is considered the perfect food for a growing young child, and we can continue to use the macronutrient ratio of breast milk as a general guide for children’s diets for as long as they are growing; after all, the macronutrient ratio of breast milk is often used as a guide for carbohydrate consumption for adults! (See also The Best Dairy Choice for Growing Children).

The macronutrient ratio of human breast milk is quite variable, depending on the diet of the mother, the frequency with which the baby nurses, and the age of the baby. It is likely that much of this variability reflects the baby’s specific dietary needs at the time. The carbohydrate content of breast milk varies from 57 to 70 percent of total milk solids. Fat makes up 28 to 39 percent of total milk solids, and protein makes up 7 to 10 percent of total milk solids. Translating each of these numbers to a percentage of caloric intake—a far more familiar number to most of us—the carbohydrate content of breast milk is 40 to 55 percent, the fat content is 40 to 55 percent, and the protein content is about 10 percent.

Human breast milk is high in fat, with approximately 40 to 55 percent of its calories coming from fat. On average, 43 percent of that fat is saturated, 37 percent is monounsaturated (including up to 7 percent of total fat being natural trans fatty acids like conjugated linoleic acid, see Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): A Rockstar Nutrient), and 20 percent is polyunsaturated. Fat is necessary for brain development, hormone regulation, and immune system development. Fat is also needed for the baby’s digestive system to absorb fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K.

Children’s carbohydrate needs vary with growth spurts, developmental spurts, and age. On average, their carbohydrate needs tend to go down as they get older (protein, in particular, begins to take the place of carbs). Caloric intake also varies dramatically with growth spurts, developmental spurts, and age, so it’s tough to convert this to a number of grams of carbohydrates a child should be eating. Instead, think of it this way: to achieve 40 percent of calories from carbohydrates, something like half to three-quarters of a child’s plate should be fruit and vegetables (including plenty of starchy vegetables; see What is a “Safe Starch”? , How Many Carbs Should We Eat? and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body). The reason 40 percent of calories from carbohydrates doesn’t translate to 40 percent of the plate being fruits and vegetables is that non-starchy vegetables are not very carbohydrate/calorie dense (especially compared to whatever fat might be on the plate).

Children’s carbohydrate needs vary with growth spurts, developmental spurts, and age. On average, their carbohydrate needs tend to go down as they get older (protein, in particular, begins to take the place of carbs). Caloric intake also varies dramatically with growth spurts, developmental spurts, and age, so it’s tough to convert this to a number of grams of carbohydrates a child should be eating. Instead, think of it this way: to achieve 40 percent of calories from carbohydrates, something like half to three-quarters of a child’s plate should be fruit and vegetables (including plenty of starchy vegetables; see What is a “Safe Starch”? , How Many Carbs Should We Eat? and The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body). The reason 40 percent of calories from carbohydrates doesn’t translate to 40 percent of the plate being fruits and vegetables is that non-starchy vegetables are not very carbohydrate/calorie dense (especially compared to whatever fat might be on the plate).

The point isn’t to suggest that we count the grams of each macronutrient that a child is eating, but rather to point out that eating a lot of fruit and vegetables is just fine for a growing child. As long as they are eating some meat and healthy fats as well and are presented with a variety of healthy options—think meat, fish, organ meat, healthy fats (such as avocados, olives, and coconut oil), green veggies, other colorful veggies, cruciferous veggies, starchy veggies, all kinds of fruit, and probiotic foods like sauerkraut—it’s generally not worth worrying about.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

First Foods FAQ

When it comes time to start feeding their babies solid foods, parents tend to have a lot of questions. Here are answers to some of the most common ones.

When should solid foods be introduced? The general rule is that you can introduce solids once your baby is at least 5 months old (6 months old is better since the gastrointestinal tract is more mature by then), is sitting up well, and is interested in your food; and you have the go-ahead from your pediatrician. Watch closely for signs of choking, and never leave a baby or toddler unattended while eating. You can help prepare your baby’s digestive tract for solids by breastfeeding exclusively (which helps provide probiotics and hormones and enzymes that help mature the digestive tract). You can also give your baby a small amount of Acidophilus Bifidus (buy a capsule that you can break open and rub a small pinch in the baby’s mouth before nursing or offering a bottle) once or twice a day, starting at about 3 months old (again, with the approval of your pediatrician). Many people prefer a baby-led weaning strategy, whereby you wait until the baby is able to self-feed soft finger foods; some babies are able to do this as early as 5 or 6 months, but 8 to 10 months is more typical. The food lists below are applicable to a baby-led weaning strategy; just cut up the food into small pieces instead of pureeing it.

What consistency should baby food be? First foods for younger babies should be thinned with breast milk, bone broth, or formula and be very runny; it should pour off a spoon and be only slightly thicker than breast milk. Over the first few months, gradually increase the thickness of the baby food. By 8 months of age, most babies can start to handle a little texture in their food (think oatmeal consistency). By 10 months, most babies can handle soft food mashed with a fork. Sometime between 8 and 10 months, your baby will probably show interest in finger foods, such as small pieces of soft fruit or cooked veggies. Watch your baby’s cues and don’t rush it.

What consistency should baby food be? First foods for younger babies should be thinned with breast milk, bone broth, or formula and be very runny; it should pour off a spoon and be only slightly thicker than breast milk. Over the first few months, gradually increase the thickness of the baby food. By 8 months of age, most babies can start to handle a little texture in their food (think oatmeal consistency). By 10 months, most babies can handle soft food mashed with a fork. Sometime between 8 and 10 months, your baby will probably show interest in finger foods, such as small pieces of soft fruit or cooked veggies. Watch your baby’s cues and don’t rush it.

What time of day should a baby be fed? Start with just one feeding a day, usually in the middle of the day, when your baby is not tired. Stop feeding as soon as your baby loses interest. Your baby may eat only a few mouthfuls for the first few meals (or even few weeks of meals). You can also introduce sips of water as you are introducing foods, from either a cup (regular, sippy, or straw) or a spoon. Over the first few months, you can gradually increase the number of times a day that your baby eats. By 9 or 10 months of age, most babies will happily eat three solid meals a day and maybe even a snack or two.

How do I watch for allergies? It can take several days for an allergic reaction to a food to present itself. Introduce only one new food every 4 to 7 days (on the longer end of this range if food allergies run in your family). You do not need to give that new food every day for those 4 to 7 days; one or two exposures is sufficient. Watch for symptoms such as:

- hives or welts

- flushed skin or rash

- swelling of face, tongue, or lips

- vomiting and/or diarrhea

- inconsolable crying

- coughing or wheezing

- difficulty breathing

- loss of consciousness

When it comes to introducing high-allergy foods like berries, tomatoes, nuts, shellfish, citrus, and egg whites, it’s best to wait until your baby is at least 1 year old.

Is it easy to make your own baby food? Not only is it quite easy, but it yields much more nutritious and tastier food. To save time, make a fairly big batch of individual ingredient purees and freeze (before thinning so that you can control the thickness as you baby gets older) in ice cube trays; once the food is frozen, you can pop the cubes into a bag and label the bag for easy defrosting later.

Can foods be mixed together? Absolutely! Play with different combinations. Something that might seem odd to you might taste delicious to your baby. And most babies prefer one taste at one meal, so mixing foods together is a great way to increase variety and balance nutrition—for example, most babies would rather their meal of sweet potato, avocado, broccoli and chicken be all mixed together into a single puree. Just make sure to use only ingredients that you’ve introduced before (or add only one new food at a time).

Can foods be mixed together? Absolutely! Play with different combinations. Something that might seem odd to you might taste delicious to your baby. And most babies prefer one taste at one meal, so mixing foods together is a great way to increase variety and balance nutrition—for example, most babies would rather their meal of sweet potato, avocado, broccoli and chicken be all mixed together into a single puree. Just make sure to use only ingredients that you’ve introduced before (or add only one new food at a time).

What are the best first foods? The best first foods for most babies are mashed ripe avocado, mashed ripe banana, mashed cooked sweet potato, mashed cooked winter squash, pureed liver (preferably pastured or grass-fed), and mashed or crumbled pastured egg yolk. For babies who are at least 6 months old, well-cooked meats very well pureed with broth or breast milk and grass-fed whole milk yogurt are excellent early foods. Babies can usually start digesting well-cooked pureed green veggies at around 6 months, too.

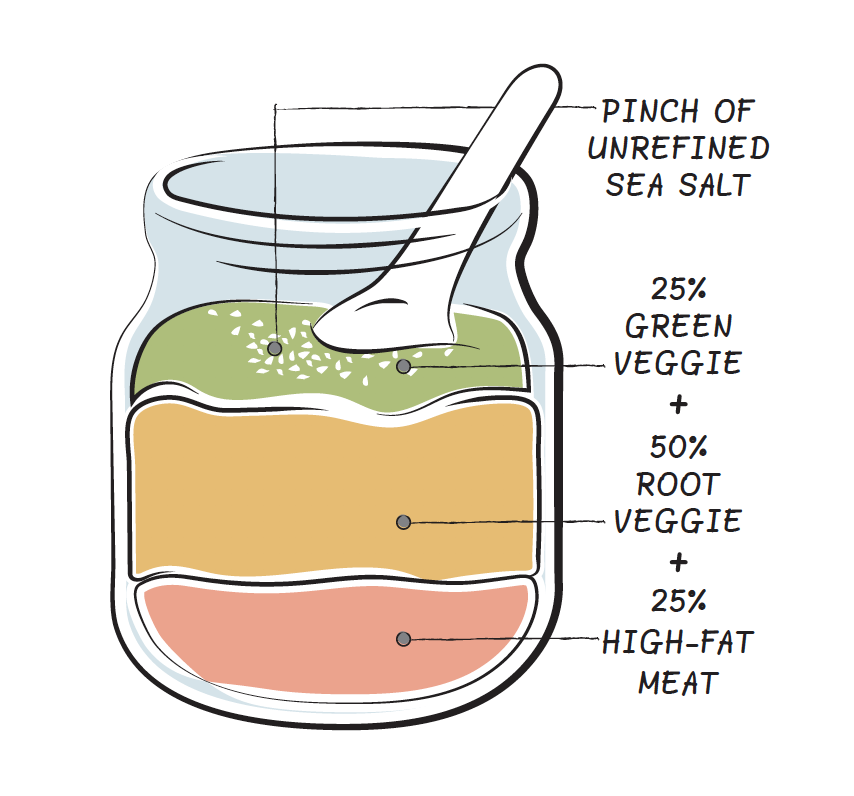

What goes into a balanced baby meal? Once you have introduced single foods to rule out allergies, your little one will be ready for balanced meals. A meal should consist of mostly fat and carbohydrates (something like 40 to 50 percent of calories each) with a moderate amount of protein (ballpark 10 percent of calories). Choose whole, preferably organic vegetables, fatty fruits like avocados, and quality meats. Making a puree with a mixture of cooked vegetables (including a sweeter starchy veggie like sweet potato and a green veggie like kale or broccoli) and meat is an easy way to achieve this balance as well as cater to a baby’s typical preference to eat only one flavor at any given meal. There’s no need to count carb and fat grams, though; this simple rubric will get you into the right ballpark for a balanced baby meal:

Balanced meal puree = 25% high-fat meat + 50% root veggie + 25% green veggie + pinch of unrefined sea salt

Puree the ingredients in a food processor or blender until smooth and thin with breast milk, broth, cooking liquid, or formula. Store extra baby food in small freezer-safe containers in the freezer for up to 3 months.

Simplify with Serenity Kids Paleo Baby Food!

Simplify with Serenity Kids Paleo Baby Food!

If you’re looking for a Paleo baby food option that’s as simple as grab-and-go, check out Serenity Kids! These baby food pouches have the same perfect ratio of fat to protein to carbohydrates as breast milk, and are made with grass-fed and pasture-raised meats, organic vegetables and healthy fats. They come in simple squeeze packs to make it easy for you and baby to handle, plus, they’re delicious (yes, I’ve tasted them, and no, that’s not weird! LOL).

I love that Serenity Kids baby foods:

- are high in healthy fats, low in sugar and are ideal early foods for babies over six months

- include only premium, humanely-raised meats and organic veggies

- are totally free of hormones, antibiotics, GMOs, gluten, fillers, grain, dairy, corn, allergens, eggs and nuts

- are completely shelf stable for a year after manufacture

- are sourced from small, American family farms practicing regenerative agriculture

- taste great, so older babies and toddlers will love them too!

I also adore the good folks behind Serenity Kids and am so impressed with their passion and attention to detail! In fact, I agreed to be a member of their advisory board, so I can completely attest to how awesome their baby foods are! You can also download an awesome guide on baby nutrition that I co-created with Serenity Kids here.

If you’ve got a little one at home and are looking for a convenient nutritionally-balanced healthy and Paleo baby food, I can’t recommend Serenity Kids enough! You can check them out here.

Citations

Nutrition in Pediatrics: Basic Science, Clinical Applications By Duggan, Christopher, John B. Watkins, and W. Allan Walker. Published by BC Decker Inc. 2008

Hascoët JM et al. Effect of formula composition on the development of infant gut microbiota. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Jun;52(6):756-62. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182105850.

Hewlett BS & Lamb ME, eds. Hunter-gatherer Childhoods: Evolutionary, Developmental, and Cultural Perspectives. Transaction Publishers. 2005.

Hirsch J, et al. “Diet composition and energy balance in humans.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Mar;67(3 Suppl):551S-555S.

Kunisawa J, et al. “Dietary ω3 fatty acid exerts anti-allergic effect through the conversion to 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid in the gut.” Sci Rep. 2015 Jun 11;5:9750.

Rindi G. Thiamin. In: Ziegler EE, Filer LJ, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 7th ed. Washington D.C.: ILSI Press; 1996:160-166.

Stuebe A. “The Risks of Not Breastfeeding for Mothers and Infants.” Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Fall; 2(4): 222–231.