Regulating blood sugar levels is a key feature of the Paleo diet. In fact, this may be the critical mechanism responsible for the observed benefits of a Paleo diet in managing diabetes that has been proven in clinical trials. Generally, blood sugar levels are well regulated as soon as we focus on eating a variety of meat, seafood, eggs, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds (click here for Paleo Diet basics).

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

But, it’s human nature to find ways around the rules. A huge variety of recipes for Paleo-friendly, grain-free, dairy-free baked goods have found their way onto blogs (mine is no exception) and cookbooks (again, mine too). And a huge variety of pre-made, packaged sweet treat products are now available for sale, making getting a treat even easier. I really do believe that there is a place in our diet and our lives for the occasional treat (read this post for more), but that doesn’t mean that anything goes. And even if a treat is occasional, the ingredients matter.

Some ingredients (like emulsifiers) are uniformly recognized as being unhealthy choices. For others (like almond flour), there’s some pros and cons to consider in determining whether they are a good choice for you as an individual. And yet other ingredients are very unhealthy choices but are erroneously promoted as healthy alternatives to sugar! These ingredients are finding their way into recipes and packaged treats marketed to the Paleo community–and that is the reason for this post. There’s a concept that if a Paleo treat is made with a sugar alternative–like agave, stevia, xylitol, or erythritol–and is thus “low-carb” or “low glycemic index”, that that makes it a good choice for a more frequent indulgence. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Some ingredients (like emulsifiers) are uniformly recognized as being unhealthy choices. For others (like almond flour), there’s some pros and cons to consider in determining whether they are a good choice for you as an individual. And yet other ingredients are very unhealthy choices but are erroneously promoted as healthy alternatives to sugar! These ingredients are finding their way into recipes and packaged treats marketed to the Paleo community–and that is the reason for this post. There’s a concept that if a Paleo treat is made with a sugar alternative–like agave, stevia, xylitol, or erythritol–and is thus “low-carb” or “low glycemic index”, that that makes it a good choice for a more frequent indulgence. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Alternatives to Glucose

Any food that causes elevated blood glucose is not conducive to health. The detrimental health impact of high blood glucose levels and high blood insulin levels are detailed in The Paleo Approach. Because of the direct link to diabetes and obesity, this is also becoming public knowledge.

Because excessive glucose consumption is so problematic, there has been a surge in low glycemic-index sweeteners, heavily marketed to diabetics and those on low-carb diets, which fall into three categories:

- Sugars that do not impact blood-glucose levels as quickly or substantially as glucose or glucose- based starches, which are marketed as low-glycemic-index sugars (fructose, inulin)

- Sugar alcohols (sorbitol, xylitol, erythritol)

- Nonnutritive sweeteners, including acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, and sucralose, as well as the “natural” sugar substitute stevia

Our bodies are not designed to metabolize these sugars in the large quantities found in processed foods. Yes, even foods and tabletop sweeteners that are marketed as “natural sweeteners” (such as agave nectar and stevia) are not actually natural for our bodies. In most cases, consuming these glucose substitutes is more harmful than consuming glucose itself. I discussed fructose in this post and stevia this post. Now let’s focus on the detrimental health effects of sugar alcohols and nonnutritive sweeteners.

Sugar Alcohols

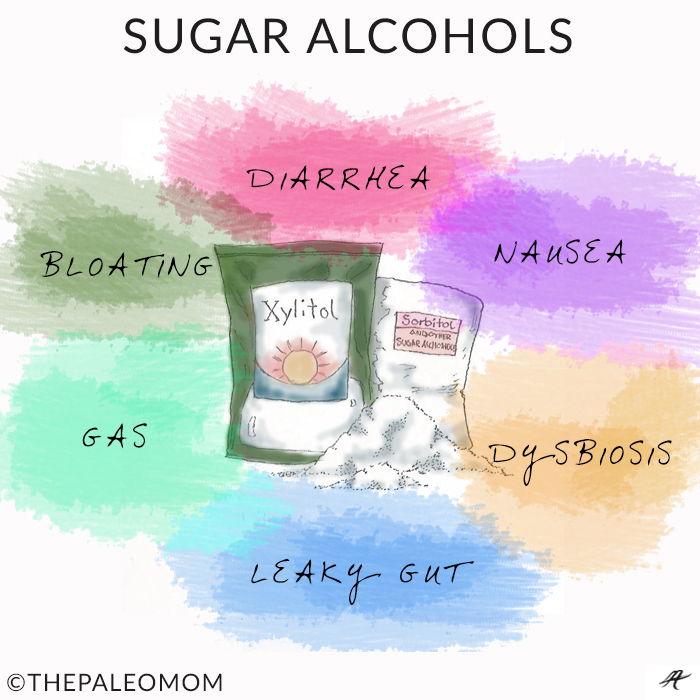

Sugar alcohols (also called polyols, which are discussed again on pages 210-212 in The Paleo Approach) are hydrogenated forms of sugars, meaning that they contain a hydroxyl group, which is what makes them technically alcohols. They are naturally occurring sugars, typically found in small quantities in fruit. However, some sugar alcohols have been refined and purified for use as sweeteners, including sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and erythritol. These sugar alcohols have gained popularity as sugar substitutes because while they are relatively less sweet, they also have less of an impact on blood-glucose levels.

Sugar alcohols are passively and, with the exception of erythritol, incompletely absorbed in the intestine. They are also fermentable sugars, which means that they feed gut bacteria. In fact, the most common side effects of sugar-alcohol consumption are severe gastrointestinal symptoms, such as watery stool, diarrhea, nausea, bloating, flatulence, and borborygmus (the rumbling noise produced by the movement of gas through the intestines). The dose required to produce the side effects varies depending on the specific sugar alcohol and the sensitivity of the individual.

There is evidence that sugar alcohols disproportionately feed Gram-negative bacteria and may contribute to gut dysbiosis. The health of the gut microbiome is increasingly recognized as critical for human health. Overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli has been shown to cause inflammation, stimulate the immune system, and is linked to a variety of chronic diseases. This is also the most common form of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO). Gut dysbiosis, such as SIBO, can also directly cause a leaky gut

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Furthermore, one study showed that the sugar alcohols xylitol and mannitol increase permeability of epithelial cells (in a cell culture system) by directly opening up tight junctions. Tight junctions are the structures that hold epithelial cells together to create a solid barrier (read more about the intestinal barrier here). When a substance causes the tight junctions to open, this causes a leaky gut.

Furthermore, one study showed that the sugar alcohols xylitol and mannitol increase permeability of epithelial cells (in a cell culture system) by directly opening up tight junctions. Tight junctions are the structures that hold epithelial cells together to create a solid barrier (read more about the intestinal barrier here). When a substance causes the tight junctions to open, this causes a leaky gut.

Another study showed that erythritol has a similar effect on tight junctions and does cause increased permeability of the epithelial barrier. Again, this means that erythritol, generally regarded as the safest sugar alcohol, can directly cause a leaky gut. To make matters worse, erythritol has also been shown to increase the virulence of bacteria from the Brucella genus, which includes pathogenic bacteria found in contaminated, unpasteurized milk.

While the effect of sugar alcohols on intestinal permeability in humans has yet to be studied, this should be enough evidence for avoiding their refined forms.

Nonnutritive Sweeteners

Nonnutritive sweeteners are substances that taste sweet but don’t provide substantial calories. They include acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, and sucralose, as well as the “natural” sugar substitute stevia (see this post) and have been linked to increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome. For example, studies have shown that the more diet soda you consume, the more likely you are to be overweight or obese and to develop metabolic syndrome; sugar-free soda, it turns out, has a greater impact on these conditions than any other dietary factor. In fact, in animal studies, the consumption of nonnutritive sweeteners causes a significant increase in body weight even with no change in food intake, which implies that these sweeteners affect metabolism or hormones.

In some people, the consumption of nonnutritive sweeteners causes the release of insulin in what is called cephalic phase insulin release. This means that the body releases insulin upon tasting something sweet in anticipation of a blood-sugar increase (because the sweet-taste receptors on the tongue generate nerve impulses that are relayed to the brain). In the case of sugar consumption, this prerelease of insulin helps control blood-sugar levels. However, in the case of nonnutritive sweeteners, this causes hyperinsulinemia (because of the absence of elevated blood sugar), the effects of which were discussed starting on page 120 in The Paleo Approach. Cephalic phase insulin release seems to happen in some people and not others, and why is not clearly understood.

Recent studies show that nonnutritive sweeteners have physiological effects that alter appetite and glucose metabolism. There is evidence that these sweeteners bind to receptors on enteroendocrine cells (specialized cells in the gastrointestinal tract that interact with the endocrine system and secrete hormones) and pancreatic islet cells (cells in the pancreas that secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon). By interacting with these endocrine cells, nonnutritive sweeteners can either stimulate or inhibit hormone secretion. In particular, there is evidence that nonnutritive sweeteners cause an increase in the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1; see this post on the Hormones of Hunger or see page 132 in The Paleo Approach) by enteroendocrine cells, which signals to the pancreas to increase the secretion of insulin and decrease the secretion of glucagon. Again, this results in hyperinsulinemia in the absence of elevated blood sugar.

There may also be some direct effects of nonnutritive sweeteners on inflammation. For example, aspartame increases oxidative stress and inflammation in the brain, although how remains unknown.

Take-Home Message

Consuming sugar alcohols or nonnutritive sweeteners in lieu of “regular” sugar is like going from the frying pan to the fire. As much as excessive glucose is harmful, these alternatives are even more so. Fructose-based sweeteners like agave nectar (discussed in this post) and stevia (discussed in this post) aren’t good choices either.

There is no way to cheat desserts. I don’t recommend any sugar substitutes. As much as high glucose levels are detrimental, the body can actually handle real sugar better than it can any of the manufactured or isolated substitutes.

It’s important to emphasize that the Paleo diet is not a low-carb or no-sugar diet: treats are OK on occasion and there’s nothing wrong with consumption of starchy vegetables and fruit in moderation. But blood-sugar levels must be regulated, which means that portion size is important. Also, regulating blood sugar is much more difficult in those with a history of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, or metabolic syndrome or those who are under chronic stress or have adrenal insufficiency because of insulin resistance. It will be important for these people to keep a very close eye on their carbohydrate intake (both quality and quantity), especially initially.

I know I’m about to get inundated with questions about other sweetener options. Lucuma is pretty much the same as date sugar (it contains glucose and fructose, but is a whole fruit so it also contains some fiber, vitamins and minerals), still not a good choice in large or frequent quantities. Monk fruit stimulates Th2 cells so it’s an immune stimulator. I’m sure I’ve missed some options between all the posts on this blog about sugars and sweeteners, but that doesn’t change the conclusion. There are no good options. Seriously, blackstrap molasses is your best bet simply because of the mineral content, but it’s still sugar. I love treats, so believe me, if there was a way to enjoy a sweet food without negative health consequences, I would have found it by now.

Here’s the trick: keep your intake low. Gradually reduce how much sugar you add to your coffee, how much honey and maple syrup is in your baked goods, and how often you consume it. Yes, it takes commitment, but your taste buds will quickly adapt to a diet rich in nutrient-dense whole foods, and you will soon find that fruits and vegetables and the occasional minimally sweetened dessert will satisfy your sweet cravings. See also Natural Sugars and their Place in Paleo and Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates

Citations

Abdel-Salam, O. M., et al., Effect of aspartame on oxidative stress and monoamine neurotransmitter levels in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice, Neurotox Res. 2012;21(3):245-55

Al-Saleh, A. M., et al., Effect of artificial sweeteners on insulin secretion, ROS, and oxygen consumption in pancreatic beta cells, The FASEB Journal. 2011;25:530.1

Brown, R. J. and Rother, K. I., Non-nutritive sweeteners and their role in the gastrointestinal tract, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2597-605

Dills, W. L. Jr., Sugar alcohols as bulk sweeteners, Annu Rev Nutr. 1989;9:161-86

Mäkinen, K. K., Effect of long-term, peroral administration of sugar alcohols on man, Swed Dent J. 1984;8(3):113-24

Malaisse, W. J., et al., Effects of artificial sweeteners on insulin release and cationic fluxes in rat pancreatic islets, Cell Signal. 1998;10(10):727-33

Payne, A. N., et al., Gut microbial adaptation to dietary consumption of fructose, artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols: implications for host-microbe interactions contributing to obesity, Obes Rev. 2012;13(9):799-809

Pepino, M. Y. and Bourne, C., Non-nutritive sweeteners, energy balance, and glucose homeostasis, Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(4):391-5

Petersen, E., et al., Erythritol triggers expression of virulence traits in Brucella melitensis, Microbes Infect. 2013;15(6-7):440-9

Polyák, E., et al., Effects of artificial sweeteners on body weight, food and drink intake, Acta Physiol Hung. 2010;97(4):401-7

Rolls, B. J., Effects of intense sweeteners on hunger, food intake, and body weight: a review, Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(4):872-8

Looking for more?

Love reading my science posts? Then you’ll love reading The Paleo Approach! My New York Times bestselling book, The Paleo Approach is a complete guide to using diet and lifestyle to manage autoimmune disease and other chronic health conditions. It answers all of the whats, the whys, and the hows!

Love reading my science posts? Then you’ll love reading The Paleo Approach! My New York Times bestselling book, The Paleo Approach is a complete guide to using diet and lifestyle to manage autoimmune disease and other chronic health conditions. It answers all of the whats, the whys, and the hows!

Find The Paleo Approach at:

- All major online retailers, including Barnes&Noble, Target, Walmart, and Amazon.com.

- Costco

- Indiebound

- Book Depository