Fat and carbohydrates get plenty of press (and controversy! see Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers), but protein really deserves some time in the spotlight too! Along with being necessary for numerous functions that keep us alive (I’d say that’s pretty important!), a higher protein intake has been associated with greater thermogenesis, better preservation of lean muscle tissue (especially during weight loss), greater satiation after eating, better appetite regulation, a lower rate of weight regain after loss, better body composition, easier fat loss on reduced-calorie diets, improved blood glucose control, and greater bone density!

But, debate remains about which forms of protein are best. While animal protein has traditionally been regarded as higher quality and superior to plant-based protein, plant protein has been getting a major reputation boost recently, both as isolated products (hemp protein, pea protein, brown rice protein, and so on) and in whole-food form (ever see the “broccoli has more protein than beef” meme that occasionally pops up on Facebook?). This has led some people to believe that plants are just as good as animals (if not better!) when it comes to supplying protein.

When we look at the evidence, though, it becomes clear that plants are great sources of plenty of important things… but protein isn’t one of them! Plant protein takes a back seat to animal protein in terms of quality, digestibility, and density. Here’s why!

Understanding Protein

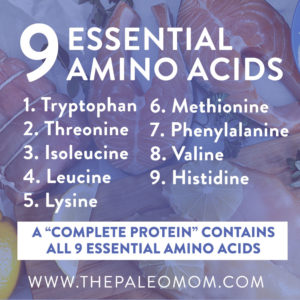

Protein is made of long chains of amino acids (organic compounds that contain a carboxyl and amino group). Even though we’ve identified about 500 different amino acids, only 20 are used to build the proteins in our bodies, and only nine of those are considered essential (meaning we can’t synthesize them from other amino acids and have to get them from food).  The essential amino acids are:

The essential amino acids are:

- Tryptophan

- Threonine

- Isoleucine

- Leucine

- Lysine

- Methionine

- Phenylalanine

- Valine

- Histidine

When we talk about a food being a “complete protein,” it means that the food contains an adequate proportion of all nine of the essential amino acids. In general, animal foods supply complete protein, whereas plant foods tend to be low in at least one essential amino acid. That’s why we see advice for vegetarian foods to be paired together (or at least eaten within the same day) to fill in each other’s gaps (such as the classic combination of rice and beans: beans are low in methionine but high in lysine, whereas rice is low in lysine but high in methionine!). The small number of plant foods that do have complete protein include quinoa, soybeans, chia, hempseeds, buckwheat, potatoes, pumpkin seeds, cashews, and a handful of others!

But, even the idea of complete protein can be misleading. Some amino acids become essential during times of illness or stress (arginine, cysteine, glutamine, tyrosine, glycine, ornithine, proline, and serine). And, even non-essential amino acids are important to consume in our diet, both because the process of synthesizing them can be inefficient and because many of them play roles in the body that go beyond protein synthesis (for example, check out “Why Broth is Awesome” to see why glycine and proline totally rock!).

On top of that, protein “completeness” doesn’t reflect bioavailability (how well our bodies actually digest and absorb the amino acids). That’s where protein quality becomes important!

Protein Quality

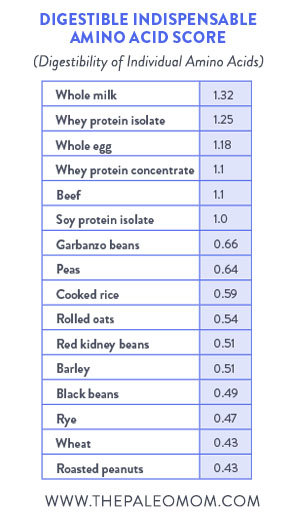

A number of methods have been used to assess protein quality, but the newest and most comprehensive one (promoted by the Food and Agriculture Organization) is the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). This method measures the digestibility of individual amino acids by analyzing fecal matter at the end of the small intestine (in contrast to the previous protein ranking standard, the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS), which measures absorption throughout the digestive system and doesn’t take into account protein absorption by gut bacteria!). The DIAAS score is calculated based on individual amino acid digestibility, the original amino acid content of food, and human amino acid requirements. The higher the score, the higher the protein quality. Here are some measurements of common foods:

- Whole milk: 1.32

- Whey protein isolate: 1.25

- Whole egg: 1.18

- Whey protein concentrate: 1.1

- Beef: 1.1

- Soy protein isolate: 1.0

- Garbanzo beans: 0.66

- Peas: 0.64

- Cooked rice: 0.59

- Rolled oats: 0.54

- Red kidney beans: 0.51

- Barley: 0.51

- Black beans: 0.49

- Rye: 0.47

- Wheat: 0.43

- Roasted peanuts: 0.43

As we can see, animal foods dominate the top of the chart when it comes to protein quality, whereas plant sources—especially whole food plant sources—trail significantly behind!

Protein Density

Another issue with plant protein involves density. Along with antinutrients that inhibit absorption (which lower protein quality scores), even the highest sources of plant protein come packaged with carbohydrates (including fiber) that dilute the protein per bite we can get from those foods (unless the food is processed and refined into smithereens and sold as a protein powder—but in that case, we’re talking about supplements, not nutrient-dense whole foods!). Conversely, animal products tend to be extremely protein dense, and lean meats and seafood can contain the vast majority of calories in the form of protein (for example, chicken breast is 80% protein and light tuna is 94% protein!). Meanwhile, plant foods we consider “high protein” contain only a fraction of that (garbanzo beans are 19% protein, almonds are 13% protein, and quinoa is 15% protein; soybeans top the list at 30% protein). There’s nothing wrong with the fiber and nutritive carbohydrates in whole plant foods (in fact, those things are pretty great), but when it comes to serving as dense sources of protein, plant foods aren’t taking home any trophies!

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Plant vs. Animal Protein in Studies

Along with providing building blocks for protein synthesis in our bodies, different sources of protein have different effects on our health. In numerous studies, diets containing only or mostly plant protein (vegetarians and vegans) have been associated with lower bone density and higher fracture rates. For athletes, animal protein (especially from meat) appears to support muscle growth and reduce the breakdown of lean mass more than vegetarian sources of protein. And, one controlled trial showed that plant protein (in the form of soy) failed to raise participants’ metabolic rates, diet-induced thermogenesis, and 24-hour spontaneous physical activity as much as animal protein (in the form of pork).

Along with providing building blocks for protein synthesis in our bodies, different sources of protein have different effects on our health. In numerous studies, diets containing only or mostly plant protein (vegetarians and vegans) have been associated with lower bone density and higher fracture rates. For athletes, animal protein (especially from meat) appears to support muscle growth and reduce the breakdown of lean mass more than vegetarian sources of protein. And, one controlled trial showed that plant protein (in the form of soy) failed to raise participants’ metabolic rates, diet-induced thermogenesis, and 24-hour spontaneous physical activity as much as animal protein (in the form of pork).

What If You’re Vegetarian for Religious (or Other Non-Health) Reasons?

Although an omnivorous diet is definitely optimal for supporting human health (see The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 2: Physiological & Biological Evidence and The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?), people who choose vegetarian diets for other reasons can still have an adequate protein intake by planning their diets wisely! There aren’t any amino acids exclusive to animal foods, and true protein deficiency is rarely seen outside of chronic starvation (protein-energy malnutrition, or kwashiorkor), crash diets, and medical conditions that result in malabsorption (including celiac disease and Crohn’s disease)—so developing a frank deficiency due to a plant-based diet is really unlikely.

The best ways for vegetarians to get a wide and sufficient intake of amino acids is by eating a diverse diet (a variety of whole plant foods each day), consuming adequate calories (or in the case of weight loss diets, a small calorie deficit that promotes slow but steady fat loss rather than a drastic reduction in energy intake), optimizing digestion to avoid malabsorption, and consuming plenty of eggs or high-quality dairy if they’re tolerated (in the case of lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets). Although these diets will be missing out on other benefits of animal foods, they can still provide a spectrum of essential and non-essential amino acids to support good health.

Let’s Keep Eating Plants… Just Not For Their Protein!

Just because plants aren’t all-stars when it comes to protein doesn’t mean they’re not the bomb in other ways! Plants provide us with fermentable fibers to feed our gut (see What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good?, The Many Types of Fiber, and Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber), an amazing array of phytochemicals—including polyphenols, flavonoids, lignans, carotenoids, chlorophyll, isothiocyanates, organosulfur compounds, sterols, and stanols  (check out The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals and Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?), as well as important micronutrients present only in low quantities in animal foods (see The Importance of Nutrient Density, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?, and 3 Ways to Up Your Nutrient Game). Bottom line: we shouldn’t eat plants for their protein, but we should eat them for all the other amazing things they contain!

(check out The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals and Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?), as well as important micronutrients present only in low quantities in animal foods (see The Importance of Nutrient Density, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?, and 3 Ways to Up Your Nutrient Game). Bottom line: we shouldn’t eat plants for their protein, but we should eat them for all the other amazing things they contain!

Citations

Bounous G. “Whey protein concentrate (WPC) and glutathione modulation in cancer treatment.” Anticancer Res. 2000 Nov-Dec;20(6C):4785-92.

Cervantes-Pahm SK, et al. “Digestible indispensable amino acid score and digestible amino acids in eight cereal grains.” Br J Nutr. 2014 May;111(9):1663-72.

Halton TL & Hu FB. “The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review.” J Am Coll Nutr. 2004 Oct;23(5):373-85.

Hannan MT, et al. “Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study.” J Bone Miner Res. 2000 Dec;15(12):2504-12.

Hoffman JR & Falvo MJ. “Protein—Which is Best? ” J Sports Sci Med. 2004 Sep;3(3):118-130.

Mikkelsen PB, et al. “Effect of fat-reduced diets on 24-h energy expenditure: comparisons between animal protein, vegetable protein, and carbohydrate.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Nov;72(5):1135-41.

Pannemans DL, et al. “Effect of protein source and quantity on protein metabolism in elderly women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Dec;68(6):1228-35.

“Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition.” World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2007.

Rutherfurd SM, et al. “Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores and digestible indispensable amino acid scores differentially describe protein quality in growing male rats.” J Nutr. 2015 Feb;145(2):372-9.

Veldhorst M, et al. “Protein-induced satiety: effects and mechanisms of different proteins.” Physiol Behav. 2008 May 23;94(2):300-7.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, et al. “High protein intake sustains weight maintenance after body weight loss in humans.” Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Jan;28(1):57-64.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, et al. “Dietary protein, weight loss, and weight maintenance.” Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29:21-41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141056.