What if there were a simple way to lose weight that didn’t require going uber low-carb, cutting fat, spending extra money, buying special products, taking pills, or completely avoiding foods you love? Actually, there is… and it’s called portion control!

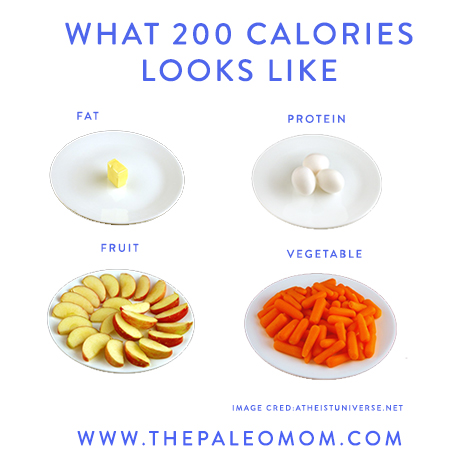

Okay, that doesn’t sound very glamorous and you might associate the concept of portion control with some pretty negative things, like deprivation, calorie counting, and feeling hungry. But, portion control doesn’t automatically imply “dieting”. What it means is that, whether conscientious or the natural result of a diet’s structure, the amount of energy in the food we eat is controlled. Typically, that implies that we’re consuming fewer calories than we’re burning, also called an energy deficit, which is permissive for weight loss.

The fact is that portion control works. In fact, portion control is the driving force behind virtually every successful weight-loss diet (whether it be low-carb, Paleo, the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet, Weight Watchers or any number of short-lived fads). No matter what a diet’s official rationale is, it induces weight loss chiefly by reducing the number of calories consumed. Different diets go about doing this in different ways, but energy intake (and portion size) is what ultimately ends up changing the numbers on the scale!

A large body of scientific literature confirms this concept. When calorie intake is held constant, different macronutrient ratios (such as low carb/high fat or high carb/low fat) don’t have a significantly different effect on the amount of body fat we lose (or on our overall energy needs). There’s no substantial evidence that specific macronutrient ratios have a “metabolic advantage” when it comes to burning more fat or changing our energy needs; the only thing that ends up influencing body mass is the calorie content of our diet. For example, a metabolic ward study from 1992 (where subjects were fed tightly controlled diets with equal calorie contents) found no detectable difference in the amount of energy people burned when eating extremely high fat, low carb diets (70% fat and 15% carbohydrate) versus extremely low fat, high carb diets (0% fat and 85% carbohydrate). And, another metabolic ward study found that when hypercaloric diets with different macronutrient compositions were compared, calories alone accounted for people’s body fat gain. (That being said, some studies have found an advantage to eating higher levels of protein when it comes to preserving lean mass (muscle) or burning a higher proportion of body fat relative to other tissue. But, those findings aren’t consistent across all studies, and in some cases are gender-specific (with women having a greater advantage when it comes to lean mass preservation from high-protein diets.) Ultimately, the research consistently shows that the most important component of weight loss is being in a negative energy balance (see also New Scientific Study: Calories Matter, Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, Tips and Tricks for Losing Weight, 3 (Surprising) Things That Might Be Stalling Your Weight Loss and The Link Between Sleep and Your Weight).

But, just because weight loss boils down to calorie intake doesn’t mean that all diets are created equal when it comes to portion control! Many modern processed foods (particularly ones rich in refined carbohydrate, vegetable oils, salt, and sugar, and low in protein) are designed specifically to induce over-eating and override our satiety signals, especially when compared to whole foods closer to their natural state. For decades, rodent experiments have shown that energy dense diets (high in fat, refined carbohydrate, and total calories) result in overeating and obesity relative to lower-energy-density diets. In fact, an interesting study from 2014 found that energy dense food (equivalent to potato chips) strongly activated the reward system of rat’s brains, leading to something called hedonic hyperphagia (eating for pleasure rather than to fulfill energy needs). This effect was not seen when the rats ate fat or carbohydrate separately! A similar phenomenon occurs in humans under the same conditions.

Not surprisingly, food manufacturers have capitalized on the well-known effect of energy density on eating behavior to create products that we want to keep eating, even when we aren’t really hungry (think of the Lay’s potato chip slogan, “Bet you can’t eat just one!”). This is part of why foods like pastries, cookies, chips, pizza, and other dense combinations of fat and carbohydrate are so strongly linked with obesity across the globe: they’re harder to stop eating when we’re full. And, it helps explain why diets that eliminate high-fat, high-carb, energy-dense foods tend to result in a spontaneous reduction of energy intake (and thus weight loss). This applies to the entire spectrum of low-carb diets, Paleo, the Mediterranean diet, low fat plant-based diets… on and on!

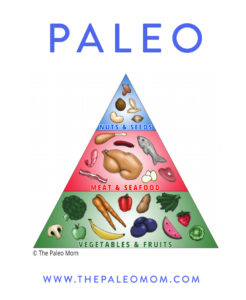

So, apart from avoiding foods that trigger overeating, how can we create a diet that lets us spontaneously reduce our portion sizes and lose weight without much effort? Here’s where Paleo has a huge leg up over many other diets! Because a well-designed Paleo diet will be loaded with fibrous plant foods (think: dark leafy greens, seaweeds, tubers, fermented vegetables, berries, and a huge spectrum of colorful veggies) alongside highly-satiating quality meats (think: organ meat, grass-fed beef, pasture-raised pork and poultry, fish and shellfish), the energy density will naturally be much lower than the Standard American Diet, and we’ll be getting fewer calories (but more micronutrients!) per bite. Plus, some evidence suggests that certain vitamins and minerals help regulate appetite, so a Paleo diet might also assist with weight loss by increasing our micronutrient intake. (See the post “The Importance of Nutrient Density” for more on this subject!)

So, apart from avoiding foods that trigger overeating, how can we create a diet that lets us spontaneously reduce our portion sizes and lose weight without much effort? Here’s where Paleo has a huge leg up over many other diets! Because a well-designed Paleo diet will be loaded with fibrous plant foods (think: dark leafy greens, seaweeds, tubers, fermented vegetables, berries, and a huge spectrum of colorful veggies) alongside highly-satiating quality meats (think: organ meat, grass-fed beef, pasture-raised pork and poultry, fish and shellfish), the energy density will naturally be much lower than the Standard American Diet, and we’ll be getting fewer calories (but more micronutrients!) per bite. Plus, some evidence suggests that certain vitamins and minerals help regulate appetite, so a Paleo diet might also assist with weight loss by increasing our micronutrient intake. (See the post “The Importance of Nutrient Density” for more on this subject!)

There are tens of thousands of weight-loss success stories within the Paleo community in addition to a growing number of clinical trials proving Paleo’s power for inducing weight loss. However, the magic bullet isn’t the Paleo diet itself, but rather that for most overweight people, average daily caloric intake tends to decrease while following an ad libidum Paleo diet. This is a good thing! It means that many people following a Paleo-style diet naturally consume a more appropriate amount of energy, while focusing on much more nutrient-dense foods! Generally, someone adopting to the Paleo diet with weight to lose can expect to achieve a modest caloric deficit, without feeling deprived, counting calories, or going hungry.

Let’s take a moment to note that the Paleo diet is not a weight-loss diet, but rather a diet designed to promote optimal human health. And, while they’re clearly not mutually exclusive, losing weight and gaining health aren’t the same thing. It’s the tandum increase in nutrient intake and decrease in intake of foods that cause inflammation, dysregulate hormones, are negatively impact the health of the gut, combined with a focus on activity, stress reduction, sleep and connection that leads to all the other health benefits of Paleo.

That said, when weight loss is the goal, there can still be some room for improvement when eating Paleo. For example:

- Be aware that tasty combinations of Paleo-friendly fat, carbohydrate, and salt can encourage us to eat more than we might really need (this includes Paleo desserts, adaptations of SAD comfort food-type recipes, dehydrated foods, chocolate, and baked goods like Paleo breads). Deliberately monitoring portion size with these foods can be helpful!

- A number of studies have shown that protein is the most satiating macronutrient (curbing appetite and potentially increasing thermogenesis), so emphasizing lean sources of animal protein (like seafood and grass-fed beef) as a centerpiece for meals may assist with weight loss.

- Low-moisture foods like nuts, dried fruit, and Paleo-friendly chips tend to be easier to overeat than foods with greater volume and water content. Watch out for mindless munching with these types of items!

Adding veggies to any meal will lower its energy density and provide more fiber and bulk, helping us reduce our calorie intake without even thinking about it. (Plus being a great source of nutrients, see The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?)

Adding veggies to any meal will lower its energy density and provide more fiber and bulk, helping us reduce our calorie intake without even thinking about it. (Plus being a great source of nutrients, see The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?)

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

By including awareness of portions and understanding the diet traps that lead us to eat more than our bodies need, we have a good shot of spontaneously reducing our energy intake and losing excess weight without the hassle of counting calories, weighing food, or stressing about every bite that goes into our mouths!

(Check out Tips and Tricks for Losing Weight and 3 (Surprising) Things That Might Be Stalling Your Weight Loss for some more ideas for successful weight loss!)

Citations

Bray GA, et al. “Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: a randomized controlled trial.” JAMA. 2012 Jan 4;307(1):47-55.

Farnsworth E, et al. “Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jul;78(1):31-9.

Hirsch J, et al. “Diet composition and energy balance in humans.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Mar;67(3 Suppl):551S-555S.

Hoch T, et al. “Snack food intake in ad libitum fed rats is triggered by the combination of fat and carbohydrates.” Front Psychol. 2014 Mar 31;5:250.

Jönsson T, et al. “Subjective satiety and other experiences of a Paleolithic diet compared to a diabetes diet in patients with type 2 diabetes.” Nutr J. 2013 Jul 29;12:105. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-105.

Leibel RL, et al. “Energy intake required to maintain body weight is not affected by wide variation in diet composition.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Feb;55(2):350-5.

Luscombe-Marsh ND, et al. “Carbohydrate-restricted diets high in either monounsaturated fat or protein are equally effective at promoting fat loss and improving blood lipids.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Apr;81(4):762-72.

Manheimer EW, et al. “Paleolithic nutrition for metabolic syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Oct;102(4):922-32. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.113613. Epub 2015 Aug 12. Review.

Otten J, et al. “Benefits of a Paleolithic diet with and without supervised exercise on fat mass, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016 May 27. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2828. [Epub ahead of print]

Poppitt SD & Prentice AM. “Energy density and its role in the control of food intake: evidence from metabolic and community studies.” Appetite. 1996 Apr;26(2):153-74.

Ramirez I & Friedman MI. “Dietary hyperphagia in rats: role of fat, carbohydrate, and energy content.” Physiol Behav. 1990 Jun;47(6):1157-63.

Swinburn B, et al. “Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Dec;90(6):1453-6.

Turner-McGrievy GM, et al. “Comparative effectiveness of plant-based diets for weight loss: a randomized controlled trial of five different diets.” Nutrition. 2015 Feb;31(2):350-8.