For years, potatoes have had a reputation for being an empty-calorie, high-glycemic food, leading many people to limit their consumption (or even avoid them entirely). And along with their perceived lack of nutrition, potatoes were originally considered “not Paleo” due to their high starch content and naturally occurring toxins (especially glycoalkaloids).

But, as potatoes make a comeback within the Paleo community, it’s important to survey the scientific evidence to evaluate whether these tasty tubers are a worthy component of a health-promoting diet.

Potato Nutrition: Are they really empty calories?

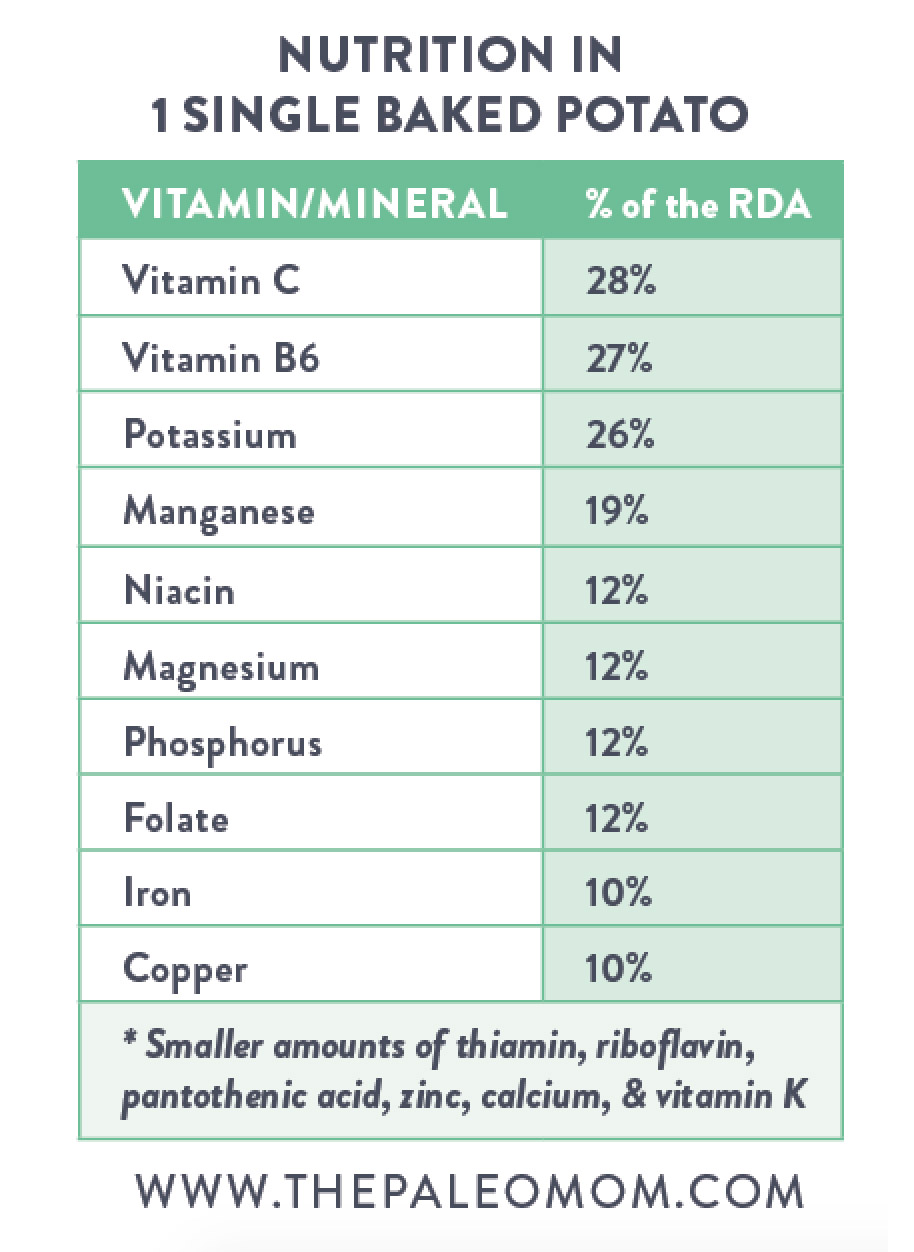

The belief that potatoes are empty calories probably stems from the fact that they’re white and high in carbohydrates (similar to true “empty calorie” foods like refined flour and refined sugar). But, this claim actually couldn’t be further from the truth! A single plain baked potato contains only 161 calories and boasts a huge array of micronutrients:

The belief that potatoes are empty calories probably stems from the fact that they’re white and high in carbohydrates (similar to true “empty calorie” foods like refined flour and refined sugar). But, this claim actually couldn’t be further from the truth! A single plain baked potato contains only 161 calories and boasts a huge array of micronutrients:

- 28% of the RDA for vitamin C

- 27% of the RDA for vitamin B6

- 26% of the RDA for potassium

- 19% of the RDA for manganese

- 12% of the RDA for niacin

- 12% of the RDA for magnesium

- 12% of the RDA for phosphorus

- 12% of the RDA for folate

- 10% of the RDA for iron

- 10% of the RDA for copper

- Smaller amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, zinc, calcium, and vitamin K

That’s actually more than twice as much potassium as a banana, and more calcium than three cups of spinach. And, in terms of vitamin and mineral content, potatoes compare favorably to other root vegetables (like carrots, turnips, rutabagas, and parsnips). Let’s put a check in the “pro” category!

Do Potatoes Have a High Glycemic Index?

Another argument against potatoes is that they have a high glycemic index (and glycemic load!), meaning they cause a relatively high blood sugar response after consumption. While this may be true in some cases (a freshly baked russet potato has a glycemic index of 111, compared to a value of 100 for an equivalent amount of pure glucose, and a glycemic load of 33 which is also considered high), the blood sugar response from potatoes is extremely context dependent! For example, cooling potatoes down after cooking (or storing them in cold environments like the refrigerator) can reduce their glycemic response significantly, which may be due to the creation of retrograded resistant starch (which not only blunts blood sugar, but can also benefit the gut microbiome and have a number of positive health effects—learn more in my post, Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses). A lower glycemic index can also be achieved by adding an acidic food to the potato (like vinegar, citrus, or salsa), eating the potato with some fat (like olive oil or avocado), increasing the fiber content of the meal (such as by eating the potato with a leafy green salad), or boiling the potato instead of baking it. Simply storing a boiled potato in the fridge overnight and adding some vinegar can reduce its glycemic index by 43%!

Another argument against potatoes is that they have a high glycemic index (and glycemic load!), meaning they cause a relatively high blood sugar response after consumption. While this may be true in some cases (a freshly baked russet potato has a glycemic index of 111, compared to a value of 100 for an equivalent amount of pure glucose, and a glycemic load of 33 which is also considered high), the blood sugar response from potatoes is extremely context dependent! For example, cooling potatoes down after cooking (or storing them in cold environments like the refrigerator) can reduce their glycemic response significantly, which may be due to the creation of retrograded resistant starch (which not only blunts blood sugar, but can also benefit the gut microbiome and have a number of positive health effects—learn more in my post, Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses). A lower glycemic index can also be achieved by adding an acidic food to the potato (like vinegar, citrus, or salsa), eating the potato with some fat (like olive oil or avocado), increasing the fiber content of the meal (such as by eating the potato with a leafy green salad), or boiling the potato instead of baking it. Simply storing a boiled potato in the fridge overnight and adding some vinegar can reduce its glycemic index by 43%!

Plus, whether or not a food’s glycemic index is really even a concern is up for debate. Many studies show no link between different foods’ glycemic index values and whether those foods associate with obesity and diabetes. In reality, the overall context of the meal is what determines glycemic response (rather than an individual food in the meal, such as a potato). And, people can have significantly different glycemic responses to the same food depending on certain gene variations (such as AMY1 copy number and the level of amylase produced in the saliva).

Not only that, but analyses of different foods’ satiety index, which measures hunger in the two hours following a meal, shows that potatoes are one of the most satiating foods out there (beating out fish, oatmeal, beef, beans, eggs, and cheese!).

Glycoalkaloids… A Real Concern

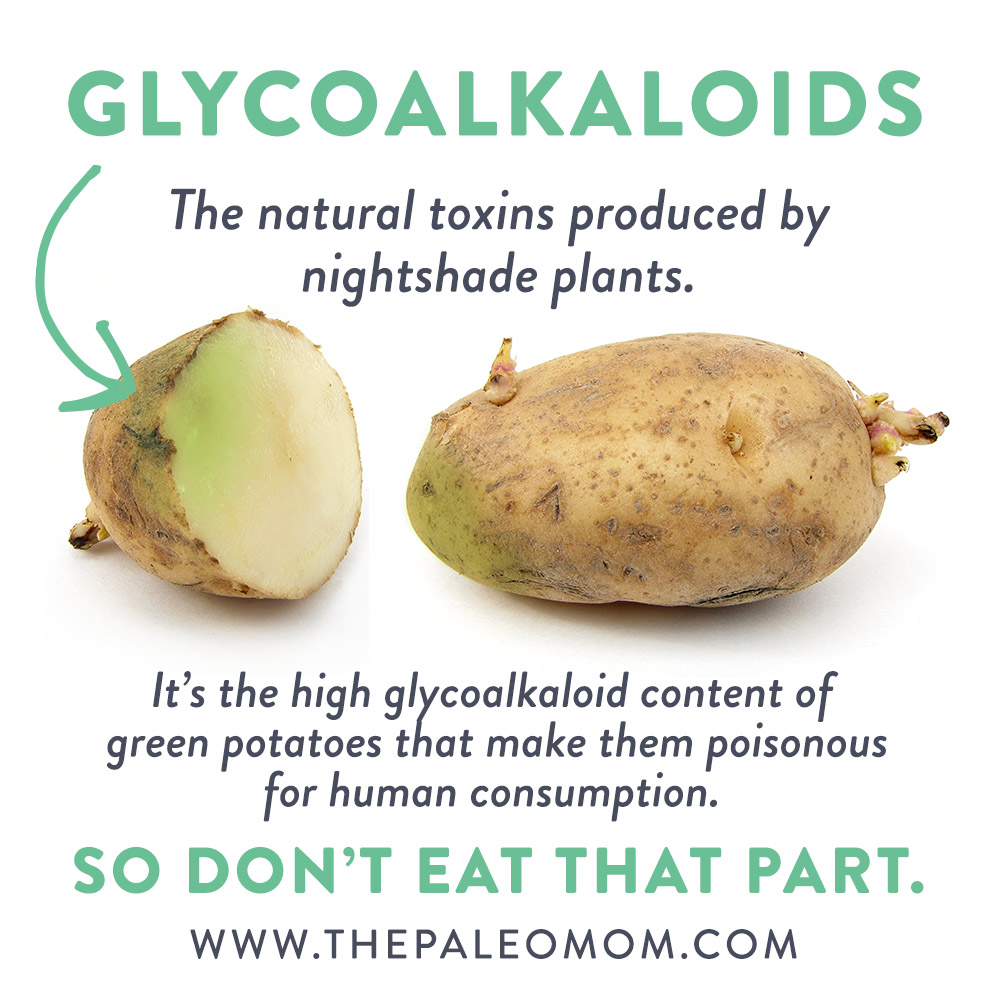

Another common concern with potatoes—and probably the most legitimate one—is their glycoalkaloid content (especially the glycoalkaloid solanine). Glycoalkaloids are natural toxins produced by nightshade plants (see, “What Are Nightshades?”) that help protect against insects, fungi, herbivores, and other predators. Unfortunately, they can also be harmful to humans! In fact, it’s the high glycoalkaloid content of green potatoes that make them poisonous for human consumption.

Another common concern with potatoes—and probably the most legitimate one—is their glycoalkaloid content (especially the glycoalkaloid solanine). Glycoalkaloids are natural toxins produced by nightshade plants (see, “What Are Nightshades?”) that help protect against insects, fungi, herbivores, and other predators. Unfortunately, they can also be harmful to humans! In fact, it’s the high glycoalkaloid content of green potatoes that make them poisonous for human consumption.

Solanum glycoalkaloids can disrupt cell membranes, induce developmental malformations, and inhibit cholinesterase (an enzyme needed for proper functioning of the central nervous system). Some of the effects of glycoalkaloid toxicity include diarrhea, intestinal permeability, weight loss, and even death. Based on reports of poisoning and death from high glycoalkaloid intake from potatoes (yep, there’s quite a few of these!), an intake of 3 to 6mg glycoalkaloids per kilogram of bodyweight is considered a potentially lethal dose for humans, while 1 to 3mg glycoalkaloids per kilogram of bodyweight is considered a toxic dose for humans. And, some researchers believe the frequent intake of potatoes may be a major contributor to the rise in chronic illness due to lower but frequent intake of glycoalkaloids. According to researcher Yaroslav I. Korpan, PhD, “This discussion suggests that potato GAs [glycoalkaloids], particularly solanine and chaconine, are extremely toxic to humans and animals, and that this problem should no longer be ignored as it could turn into a serious health threat.”

That might sound scary, but it’s important to understand that the effects of glycalkaloids depend on two things: the dose we ingest, and whether or not we currently have a chronic disease. Acute toxicity symptoms generally result from much higher levels of glycoalkaloids than we get from a moderate, or even high, intake of potatoes. (The reports of poisoning generally occurred with average portion sizes but of potatoes that had unusually high concentrations of glycoalkaloids.) The upper limit of safety for glycoalkaloids in potatoes is 20mg per 100g of potato, and commercial varieties have been deliberately cultivated to stay well below this threshold. For example, solanine (the most toxic glycoalkaloid in potatoes, typically accounting for 30-40% of the total glycoalkaloid content of potatoes) varies between cultivars:

- Red potatoes: 1.09mg /100g (fresh weight)

- White potatoes: 0.58 mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Idaho Russet potatoes: 0.65mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Washington Russet potatoes: 0.58mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Benji potatoes: 2.8mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Lenape potatoes 21.6 /100g (fresh weight)

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

However, compare those numbers to several cultivars from Pakistan that aren’t sold commercially in the US:

- SH-5 potatoes: 7.08mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Diamant potatoes: 26.87mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Cardinal potatoes: 30.83mg /100g (fresh weight)

- FD 8-3 potatoes: 2466.56mg /100g (fresh weight) — This one needs a “WOAH!”

The most comprehensive experiment studying glycoalkaloid toxicity in humans found that symptoms of poisoning emerged at 2mg of glycoalkaloid per kg of body weight (or 4.4mg per pound body weight). Assuming they’re correctly stored and prepared (more on that later!), it would take 24.6kg (or 54lbs.) of russet potatoes to deliver that amount!

However, certain people are much more sensitive to glycoalkaloids than others. In some individuals, gastrointestinal symptoms have been documented after eating potatoes with a glycoalkaloid content of only 3 to 10mg per 100g of potato (a range that many common potato cultivars and potato products fall within). And, people with autoimmune diseases (and certain other chronic conditions) can react to very low exposures that would be safe for the rest of the population. That’s because glycoalkaloids are capable of decreasing the viability of intestinal cells (AKA killing them!) and increasing epithelial permeability (resulting in leaky gut). This increase in permeability is attributable not only to the effects on cell health, but also to an effect on cell-to-cell contact. The result is an exaggerated immune response when proteins enter the bloodstream, whether due to glycoalkaloids’ direct influence on intestinal permeability or because of an already-leaky gut. That spells bad news for anyone with an autoimmune condition or other chronic disease involving compromised gut health! (Some types of glycoalkaloids also have adjuvant activity, meaning they act as immune stimulants, but this is more the case for alpha-tomatine in tomatoes than the glycoalkaloids highest in potatoes, alpha-solanine and alpha-chaconine.)

So, people with certain existing health conditions may need to eliminate potatoes to avoid triggering symptoms. But, for everybody else, there are ways to store and prepare potatoes to minimize their glycoalkaloid content. Higher levels of glycoalkaloids result from light exposure (as indicated by the greenish color potatoes can develop), so storing potatoes in dark areas is important!

So, people with certain existing health conditions may need to eliminate potatoes to avoid triggering symptoms. But, for everybody else, there are ways to store and prepare potatoes to minimize their glycoalkaloid content. Higher levels of glycoalkaloids result from light exposure (as indicated by the greenish color potatoes can develop), so storing potatoes in dark areas is important!

And, between 30 and 80% of a potato’s solanine content develops right under the skin, and in some cases, the peel contains upwards of 98% of the total glycoalkaloid content! This means that simply peeling potatoes before cooking them can also reduce their glycoalkaloid content substantially.

Levels of Total Glycoalkaloids in Potato Flesh versus Peel

- Atlantic potato peel: 8.4mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Atlantic potato flesh: 3.6mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Russet Norkotah potato peel: 42.5mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Russet Norkotah potato flesh: 6.4mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Dark Red Norland potato peel: 126.4mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Dark Red Norland potato flesh: 2.2mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Snowden potato peel: 325.6mg /100g (fresh weight)

- Snowden potato flesh: 59.1mg /100g (fresh weight)

Some research suggests that microwaving (more than boiling or other cooking methods) can also reduce levels of these toxins by about 15% (see Are Microwaves Safe to Use?). Frying potatoes in oil at 210°C (but not lower temperatures!) will also reduce glycoalkaloid levels by about 40%, but only because the glycoalkaloids get retained in the oil—which makes it easy for these toxins to get reabsorbed by potatoes if the oil isn’t changed regularly. Plus, keep in mind that this temperature is far above the smoke point for nearly all the healthy fat choices for deep frying.

Levels of Glycoalkaloids in Various Commercial Potato Products and Preparations (mg per 100g of product)

Levels of Glycoalkaloids in Various Commercial Potato Products and Preparations (mg per 100g of product)

- Boiled peeled potato: 2.7-4.2

- Baked jacket potato: 9.9-11.3

- French fries: 0.04-0.8

- Fried potato skins: 56.7-145.0

- Frozen mashed potato: 0.2-0.5

- Frozen baked potato: 8.0-12.3

- Frozen French fries: 0.2-2.9

- Frozen potato skins: 6.5-12.1

- Frozen fried potato: 0.4-3.1

- Canned peeled potato: 0.1-0.2

- Canned whole new potato: 2.4-3.4

- Potato chips: 2.3-18.0

- Chips with skin: 9.5-72.0

- Dehydrated potato flour: 6.5-7.5

- Dehydrated potato flakes: 1.5-2.3

So, Are Potatoes Paleo?

What should we make of these starchy tubers? The answer really depends on our current health situation! These tubers actually have a lot to offer us in terms of nutrients and satiating complex carbohydrates. But, they can also be a detriment to intestinal permeability, depending on the health of the person and the exact variety of potato and cooking preparation. Like many not-quite-perfect foods (tomatoes and other nightshades, nut and seeds, and eggs), moderate consumption can absolutely be considered Paleo. But, they aren’t AIP!

What should we make of these starchy tubers? The answer really depends on our current health situation! These tubers actually have a lot to offer us in terms of nutrients and satiating complex carbohydrates. But, they can also be a detriment to intestinal permeability, depending on the health of the person and the exact variety of potato and cooking preparation. Like many not-quite-perfect foods (tomatoes and other nightshades, nut and seeds, and eggs), moderate consumption can absolutely be considered Paleo. But, they aren’t AIP!

Citations

Atkinson FS, et al. “International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008.” Diabetes Care. 2008 Dec; 31(12): 2281–2283.

Aziz A, et al. “Glycoalkaloids (α-chaconine and α-solanine) contents of selected Pakistani potato cultivars and their dietary intake assessment.” J Food Sci. 2012 Mar;77(3):T58-61.

Cantwell M. “A Review of Important Facts about Potato Glycoalkaloids.” Perishables Handling Newsletter. 1996 Aug;87:26-7.

Friedman M. “Potato glycoalkaloids and metabolites: roles in the plant and in the diet.” J Agric Food Chem. 2006 Nov 15;54(23):8655-81.

Friedman M & Dao L. “Distribution of glycoalkaloids in potato plants and commercial potato products.” J Agr Food Chem. 1992; 40(3):419–423.

Friedman M & McDonald GM. “Postharvest changes in glycoalkaloid content of potatoes.” Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;459:121-43.

Holt SH, et al. “A satiety index of common foods.” Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995 Sep;49(9):675 – 90.

Korpan YI, et al. “Potato glycoalkaloids: true safety or false sense of security?” Trends Biotechnol. 2004 Mar;22(3):147-51.

Lachman J, et al. “Effect of peeling and three cooking methods on the content of selected phytochemicals in potato tubers with various colour of flesh.” Food Chem. 2013 Jun 1;138(2-3):1189-97.

Leeman M, et al. “Vinegar dressing and cold storage of potatoes lowers postprandial glycaemic and insulinaemic responses in healthy subjects.” Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005 Nov;59(11):1266-71.

Mandel AL & Breslin AS. “High Endogenous Salivary Amylase Activity Is Associated with Improved Glycemic Homeostasis following Starch Ingestion in Adults.” J Nutr. 2012 May; 142(5): 853–858.

Roddick JG & Jones JL. “Potato glycoalkaloids: Some unanswered questions.” Trends in Food Science & Technology. 1996 Apr;7(4):126-131.

Smith DB, et al. “Potato glycoalkaloids: Some unanswered questions.” Trends in Food Science & Technology. 1996 Apr;7(4):126-131.

Takagi K, et al. “Effect of cooking on contents of α-chaconine and α-solanine in potatoes.” Journal of the Food Hygienic Society of Japan. 1990;31(1):67-73.

Viljakainen H, et al. “Low Copy Number of the AMY1 Locus Is Associated with Early-Onset Female Obesity in Finland.” PLoS One. 2015 Jul 1;10(7):e0131883.