For decades, we’ve been warned that saturated fat is a dangerous substance capable of raising our cholesterol, clogging our arteries, and sending us to an early grave. Official guidelines told us to swap out animal fats for high-omega-6 vegetable oils to stay healthy (blech!). And so, natural sources of saturated fat (like butter and coconut oil) ended up getting shunned from our menus… without actually improving public health as a result.

But, the tide is finally turning for this poor nutrient! Recent meta-analyses have cast doubt on the idea that saturated fat is a major player in heart disease, and suggest the link is either very weak or nonexistent. A major 2010 paper pooled the available research and found “no significant evidence” for the saturated fat/heart disease connection we’ve been taught for decades as gospel. As a result, saturated fat has been making a major comeback, with fatty cuts of meat and saturated cooking fats no longer being feared.

But, some people have taken “saturated fat isn’t bad for you” one step further, and believe that eating more (and more and more!) saturated fat is health-promoting. In particular, some members of the low-carb and Paleo community are now striving to get as much saturated fat as possible into their diets, above and beyond what would have been possible during most of human history (before we could run to the store and stock up on 10 bricks of Kerrygold butter!).

That leads us to the question: are high intakes of saturated fat really safe, much less beneficial? Or is this a case where moderation (as much as I despise that word!) is really the best strategy? Instead of getting confused by unsubstantiated claims on the internet, let’s look at what the scientific literature has to say!

Gut Health and Endotoxins

One of the less-known issues with saturated fat is its potential impact on gut health (which plays a huge role in immunity, disease protection, mental health, obesity, allergies, and countless other conditions!).

A number of studies have shed light on the ways saturated fat can interact with our gut microbiomes, and the news isn’t always good. In mice, diets containing high amounts of saturated fat (from palm oil) cause an overflow of fat into the distal intestine, leading to an increase in the Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio (which is associated with obesity). Even though we’re not mice, a similar effect can likely occur in humans and lead to harmful changes in mucosal gene expression. In fact, some research in humans has correlated gut dysbiosis and obesity-promoting gut microbiomes with diets high in saturated fat and low in fiber.

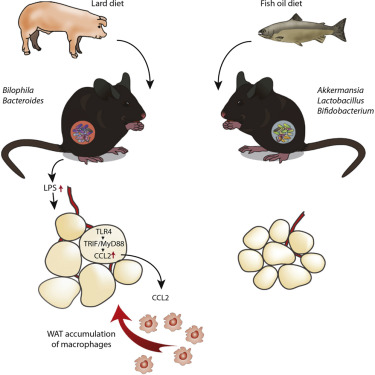

Additional rodent studies show a similar effect from high-saturated-fat foods. One experiment fed mice diets rich in either lard (high in saturated fat) or fish oil (low in saturated fat) for 11 weeks, and found that the lard diet raised the animals’ levels of Bilophila, Turicibacter, and Bacteroides, while simultaneously developing metabolic diseases. The change in microbe proportions appeared to increase inflammation through activation of toll-like receptors (namely TLR4).

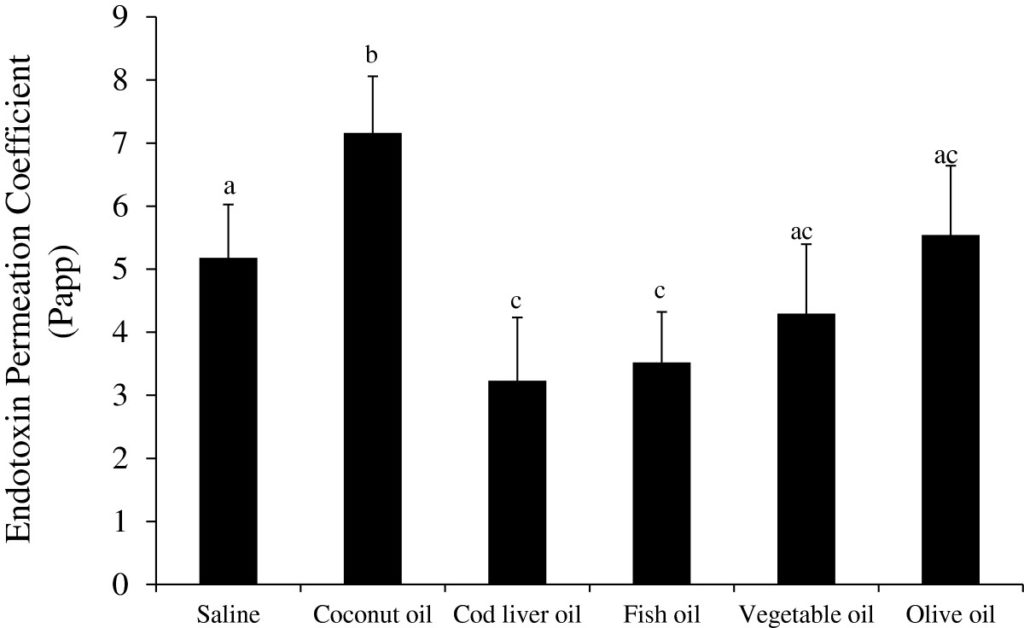

In humans and other animals, a high intake of saturated fat can also induce endotoxemia (raised levels of endotoxins in the blood). Endotoxins (also called lipopolysaccharides, or LPS) are found in the outer membrane of certain bacteria, and can trigger strong immune responses and inflammation in our bodies (in fact, endotoxemia is increasingly being viewed as an activator of metabolic diseases and other inflammation-related conditions!). In multiple trials using different types of fats (fish oil, cod liver oil, coconut oil, butter, olive oil, and vegetable oils), saturated fats clearly trigger the release of endotoxins from the gut and into the bloodstream.

Researchers are still figuring out exactly why that happens, but possible explanations are the tendency for high-saturated-fat diets to increase the abundance of gram-negative bacteria in the gut (the type of bacteria with endotoxin-containing membranes, an example being E. coli), and for saturated fat to increase the transport of endotoxins via lipid rafts. (But, it looks like there might be ways to offset the endotoxemic effect from saturated fat: at least in rodents, the addition of prebiotics (like oligofructose) lowers the endotoxin response to saturated fat, and certain fibers and phytochemicals appear to do the same! Woot for yet another imperative for consuming veggies with our meat!)

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

The Sleep Connection

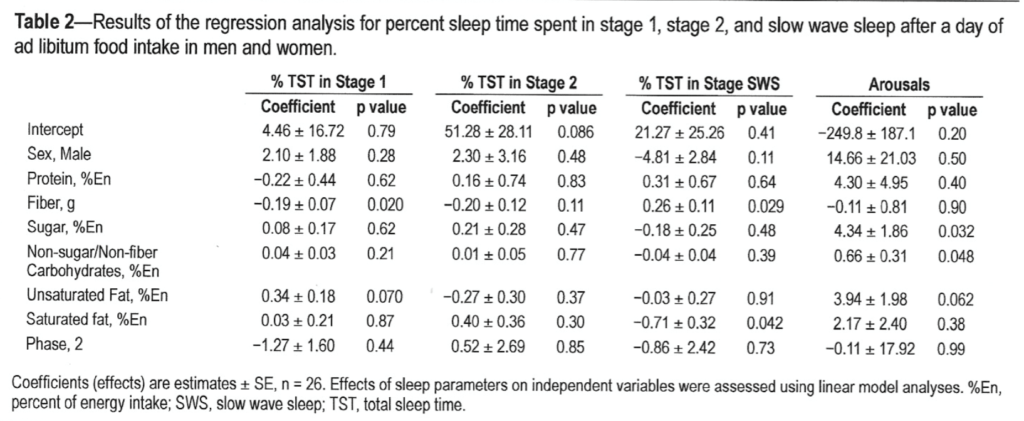

Could too much saturated fat result in less restful sleep? Some surprising new research suggests the answer is yes! A study published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine found that higher saturated fat intake was associated with lighter, less restorative, more disruptive sleep (waking up throughout the night). Yikes! This is a fascinating finding, and we need more research to explore why this connection exists and what mechanism is behind it. (For more information on this study’s other important finding—that fiber helps increase sleep quality—check out my recent post here!)

ApoE4 Carriers

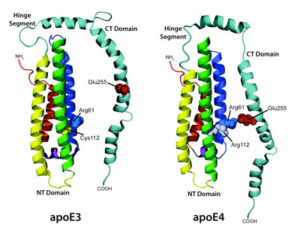

Even though saturated fat has pretty much been redeemed on the heart disease front, there’s one subset of the population that might genuinely need to limit their intake for the sake of heart-health: ApoE4 carriers!

The ApoE lipoprotein (coded by the ApoE gene) plays a major role in metabolizing and transporting cholesterol and saturated fat. All of us have two copies of the ApoE gene, which can be a combination of any of three variants: ApoE2, ApoE3, or ApoE4. While ApoE2 and ApoE3 carriers generally don’t have a noteworthy response to eating saturated fat, it turns out that ApoE4 carriers are a different story!

A number of studies show that compared to the other variants, ApoE4 carriers see a much higher spike in LDL cholesterol from eating large amounts of saturated fat (without a rise in HDL to match). And, they’re the group most likely to benefit from lower-saturated-fat diets, since decreasing their saturated fat intake causes a sharp decline in LDL cholesterol and an improvement in the HDL/LDL ratio (non-E4 carriers usually don’t see that ratio improve from going on a low-fat diet).

The scary news about ApoE4 is that for people who are born with at least one copy (about 20% of the population), the risk of heart disease (as well as Alzheimer’s disease) is much higher than the rest of the population. So, managing heart health should be on the forefront of these people’s minds… which means being conservative with saturated fat intake, and not going gung-ho on things like buttered coffee and tons of bacon. (To find out if you’re an ApoE4 carrier, a number of genetic testing services are available, including from www.23andme.com. Your doctor may be able to order an ApoE test for you as well, especially if you have a family history of heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease.)

Super High LDL

Even for non-ApoE4 carriers, some people seem to react to extremely high-saturated-fat diets with skyrocketing LDL cholesterol. Dr. Peter Attia, M.D., wrote about this topic on his blog, after seeing a number of patients’ blood lipid profiles become disconcerting after they embarked on ketogenic diets high in saturated fat. And we’re not just talking LDL concentrations that went up because the particles became big and fluffy: some people were exhibiting LDL particle counts of more than 3500 nmoL/L (more than could be measured by the NMR machine!), along with increasing levels of inflammation, as measured by C-reactive protein. As Dr. Attia explained in his blog, some of those patients were able to drop their LDL and CRP to less risky levels simply by replacing most of the saturated fat they were eating with monounsaturated fat.

Although this reaction won’t happen to everyone, it is important to realize that some people may be “hyper-responders” to saturated fat and are better off moderating their intake!

Impaired Endothelial Function

Several studies have measured the effects of meals rich in different types of fat (saturated versus unsaturated) on the function of endothelial cells, the cells that line all of the blood vessels in our bodies. The results? Not looking good for saturated fat! One experiment found that flow-mediated dilation (an artery’s ability to relax in response to shear stress) was impaired after people spent three weeks on a high-saturated-fat diet (in the form of butter). That diet also increased levels of adhesion molecules in the subjects’ blood (molecules that both endothelial cells and white blood cells use to connect with each other, allowing the white blood cells to leave the blood stream and moving into the tissue as part of an inflammatory response), relative to people who were eating monounsaturated-rich or polyunsaturated-rich diets. Another study found that a high-saturated-fat meal impaired endothelial function of the arteries, and also reduced the anti-inflammatory potential of HDL—both bad things for cardiovascular health! (Fortunately, some of these effects might be mediated by other components of the diet, such as vitamin E intake.)

What About Grass-fed/Organic Sources of Saturated Fat?

When there’s any type of bad news about animal foods, the complaint often comes up: “But the meat/dairy/etc. they used wasn’t grass-fed and organic!” After all, most of our research is done on meat and dairy from conventionally-raised animals that eat terrible diets, are exposed to extra hormones and antibiotics, and are generally sick and unhealthy. So, could that explain some of the negative effects we see from eating lots of saturated fat?

When there’s any type of bad news about animal foods, the complaint often comes up: “But the meat/dairy/etc. they used wasn’t grass-fed and organic!” After all, most of our research is done on meat and dairy from conventionally-raised animals that eat terrible diets, are exposed to extra hormones and antibiotics, and are generally sick and unhealthy. So, could that explain some of the negative effects we see from eating lots of saturated fat?

The answer is most likely no. The major concerns with saturated fat are due largely to its chemical structure, which isn’t affected by what the animal it came from was eating (although the amount of their fat that is saturated is certainly affected). And, some of the studies done on saturated fat have used coconut oil or palm oil rather than animal products, and the results were the same. So, this really isn’t something we should consider irrelevant just because we shop at the farmers market and eat higher-quality animal foods!

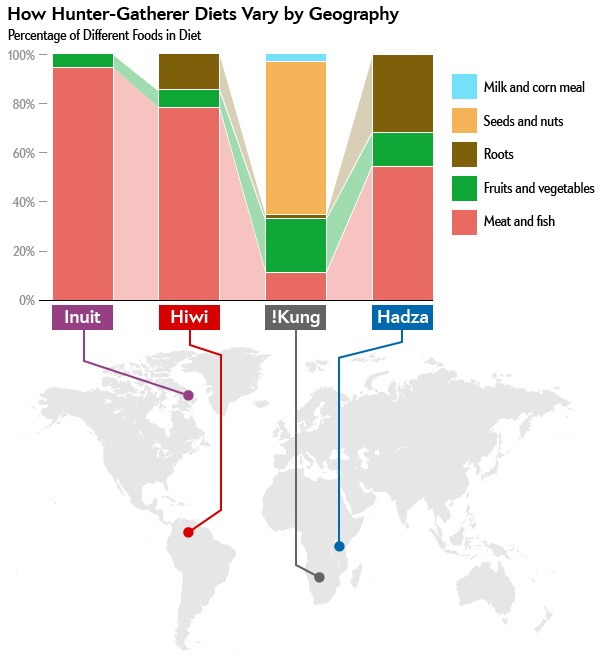

How Much Saturated Fat do Hunter-Gatherers Eat?

Even though most contemporarily-studied hunter-gatherers get more than half of their calories from animal foods and as much as 58% of their calories from fat, the average caloric intake from saturated fat among these populations is only 13% (modal range is 10-15%).

Surprised? The fat in wild game meat is much lower in saturated fat than industrially-produced (grain-fed) meat in addition to being lower fat overall (in fact, depending on the source, the fat can be up to about 50% monounsaturated and 30% polyunsaturated, compared with about 50% saturated in some fats from grain-fed animals). And while fish and shellfish do contain saturated fat, the dominant fats in seafood are monounsaturated and long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fats. Add in the fact that most plant sources of fat are monounsaturated and polyunsaturated, the 13% calories from saturated fat number starts to make some sense!

Often arguments for higher fat intake cite the Inuit and Eskimos as examples of hunter-gatherers consuming high amounts of animal products while exhibiting a lack of chronic illness compared to Western cultures. While it is certainly true that depending on the season, these peoples may get up to 90% of their caloric intake from animal foods, they’re something very unique about their diet: They get carbohydrates from the high glycogen content of the meat that they eat. (For instance, when blubber is analyzed by direct carbohydrate measurements, it has been shown to contain as much as 8—30% carbohydrates.) In addition, these peoples go to great lengths to collect nutrient-dense plant foods that provide a wide spectrum of micronutrients, prebiotics, and probiotics not available from meat and fish (including chlorophyll-rich seaweeds, berries, mosses, wild leafy greens, tubers, and the partially digested stomach contents of animals). They even ferment a number of plant foods as a way of preserving them for year-round use.

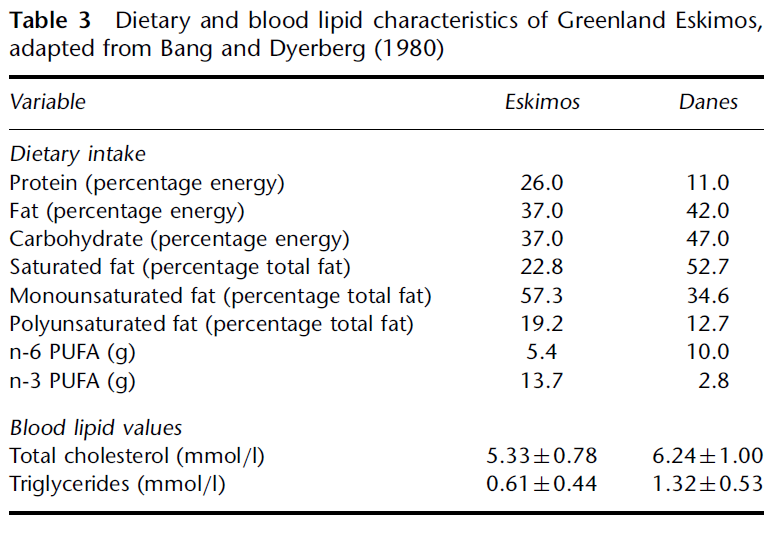

The following analysis from Cordain, et al of the Greenland Eskimo’s macronutrient intake has their saturated fat content well above other hunter-gatherers, but still at only 8% of total caloric intake (22.8% of 37% total fat).

Surprised the Eskimo’s saturated fat intake is so low as a percentage of caloric intake? Many of the animal foods they eat are seafood and sea mammals, which, while being quite fatty foods, aren’t that high in saturated fat as a percentage of total fat.

The Kitavans on the other hand often used as an example of a much more plant-centered hunter-gatherer diet, with only about 10% of their calories from protein, 69% from mostly starchy carbohydrates, and only get about 21% of their total calories from fat. However, a whopping 81% of that fat intake is saturated fat due to their high coconut intake. That puts their saturated fat intake as a percentage of total calories at about 17%, more than double the Eskimos and one of the highest saturated fat intakes among contemporary hunter-gatherers.

It’s worthy to note that hunter-gatherer saturated fat intake is certainly higher than the American Heart Association’s long-standing recommendation of under 10% total calories. But, it’s also a far cry from the high intake purported by others to lead to ever increasing health benefits or from the average 28% saturated fat consumed in the typical Western diet.

In the context of the physiological and biological research already discussed above that points to negative health impacts from too much saturated fat, hunter-gatherers provide an excellent example of that moderate middle ground.

Does This Mean We Should Eat A Low-Fat Diet?

While eating excessive amounts of saturated fat doesn’t seem to be a good idea, eating too little saturated fat could also be a problem. Why? Well, when we cut way back on saturated fat, we have to either replace those calories with other forms of fat (monounsaturated and polyunsaturated (PUFA)), or we have to eat a diet low in total fat (and fill in the rest with carbohydrates and protein).

Although monounsaturated fats are pretty neutral, we run into problems when increasing our PUFA intake (especially in the form of omega-6 fatty acids). Polyunsaturated fats have very delicate, fragile structures that are prone to oxidizing. Although they do play an important role in health when eaten in proper quantities, excessive amounts can be harmful: the PUFAs we eat become incorporated into our cell membranes and can increase our risk of free radical damage (leading to a cascade of problems such as higher cancer risk and higher risk of heart disease!). Omega-6 PUFAs in particular tend to be pro-inflammatory, especially if they’re not adequately balanced by omega-3s. So, if we try to avoid saturated fat and simply replace it with PUFAs, we’re creating a macronutrient profile with a new set of problems!

The other option, eating a diet low in total fat, isn’t a great strategy either. While there are definitely some vocal proponents of low-fat diets out there (such as Dean Ornish), the bulk of the available evidence points to low-fat diets having plenty of risks! For one, we need some dietary fat to optimize the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K (which are critical to tons of processes in our bodies). Also, low-fat diets and having low levels of serum cholesterol (which tend to go hand-in-hand) have been linked to a variety of health conditions, including depression and suicide (low-fat diets may impair serotonin receptors by decreasing the fats in nerve-cell membranes), anxiety, aggression, other violent behavior, premature death, and even cancer (fat and cholesterol are important for the integrity of cell membranes).

Overall, the research points towards a moderate fat intake (30-40% of calories, perhaps as high as 50% for some people) and moderate saturated fat intake (10-20% of calories) being ideal for maintaining all aspects of our health.

What does that look like? It’s pretty easy to hit these recommendations simply by sticking with high-quality whole-food sources of dietary fat (like a couple of eggs with breakfast, a salmon fillet at dinner, or half an avocado sliced into your salad at lunch) while using high-quality added fats (unrefined rendered fats from pasture-raised or wild animals as well as cold-pressed unrefined fats from plants like olives and avocado) in careful moderation, if not sparingly. So, no, you don’t need to trim the fat off your grass-fed steak or skip the chicken skin, but there’s compelling reasons to avoid adding half a stick of butter to your veggies or your morning coffee (I wish that was more of an exaggeration than it is).

Bottom Line

So, let’s get this totally clear! We absolutely should not fear nutrient-dense foods just because they contain saturated fat. But, we also shouldn’t go out of our way to eat as much saturated fat as possible under the belief it will make us healthier. There’s zero evidence to support that idea (despite what’s floating around on Facebook), and some research to suggest it could actually be harmful. Yes, when it comes to saturated fat intake, the “everything in moderation” mantra certainly holds true. It we stick to a Paleo diet rich in phytochemical-rich plant foods (especially vegetables), adequate fiber and prebiotics to support gut health, and reasonable quantities of high-quality meat, seafood, and eggs, we stand the best shot at boosting our health and averting disease!

Citations

Caesar R, et al. “Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota and Dietary Lipids Aggravates WAT Inflammation through TLR Signaling.” Cell Metab. 2015 Oct 6;22(4):658-68.

Campos H, et al. “Gene-diet interactions and plasma lipoproteins: role of apolipoprotein E and habitual saturated fat intake.” Genet Epidemiol. 2001 Jan;20(1):117-128.

Cani PD, et al. “Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia.” Diabetologia. 2007 Nov;50(11):2374-83.

Chang AK, et al. “Low plasma cholesterol predicts an increased risk of lung cancer in elderly women.” Prev Med. 1995 Nov;24(6):557-62.

Cordain L, et al. “Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92.

Cordain, L, et al. “The paradoxical nature of hunter-gatherer diets: meat-based, yet non-atherogenic.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2002) 56, Suppl 1, S42–S52

Corella D, et al. “Saturated fat intake and alcohol consumption modulate the association between the APOE polymorphism and risk of future coronary heart disease: a nested case-control study in the Spanish EPIC cohort.” J Nutr Biochem. 2011 May;22(5):487-94.

Cox C, et al. “Individual variation in plasma cholesterol response to dietary saturated fat.” BMJ. 1995 Nov 11;311(7015):1260-4.

de Wit N, et al. “Saturated fat stimulates obesity and hepatic steatosis and affects gut microbiota composition by an enhanced overflow of dietary fat to the distal intestine.” Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012 Sep 1;303(5):G589-99.

Erridge C, et al. “A high-fat meal induces low-grade endotoxemia: evidence of a novel mechanism of postprandial inflammation.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Nov;86(5):1286-92.

Ghanim H, et al. “A resveratrol and polyphenol preparation suppresses oxidative and inflammatory stress response to a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 May;96(5):1409-14.

Golomb BA. “Cholesterol and violence: is there a connection?” Ann Intern Med. 1998 Mar 15;128(6):478-87.

Harte AL, et al. “High fat intake leads to acute postprandial exposure to circulating endotoxin in type 2 diabetic subjects.” Diabetes Care. 2012 Feb;35(2):375-82.

Jayarajan P, et al. “Effect of dietary fat on absorption of beta carotene from green leafy vegetables in children.” Indian J Med Res. 1980 Jan;71:53-6.

Keogh JB, et al. “Flow-mediated dilatation is impaired by a high-saturated fat diet but not by a high-carbohydrate diet.” Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005 Jun;25(6):1274-9.

Lindeberg et al. “Age relations of cardiovascular risk factors in a traditional Melanesian society: the Kitava Study.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1997 Oct;66(4):845-52.

Logan AC. “Omega-3 fatty acids and major depression: A primer for the mental health professional.” Lipids Health Dis. 2004; 3: 25.

Loktionov A, et al. “Gene-nutrient interactions: dietary behaviour associated with high coronary heart disease risk particularly affects serum LDL cholesterol in apolipoprotein E epsilon4-carrying free-living individuals.” Br J Nutr. 2000 Dec;84(6):885-90.

Mani V, et al. “Dietary oil composition differentially modulates intestinal endotoxin transport and postprandial endotoxemia.” Nutr Metab (Lond). 2013 Jan 10;10(1):6.

Mänttäri M, et al. “Apolipoprotein E polymorphism influences the serum cholesterol response to dietary intervention.” Metabolism. 1991 Feb;40(2):217-21.

Muldoon MF, et al. “Effects of a low-fat diet on brain serotonergic responsivity in cynomolgus monkeys.” Biol Psychiatry. 1992 Apr 1;31(7):739-42.

Nicholls SJ, et al. “Consumption of saturated fat impairs the anti-inflammatory properties of high-density lipoproteins and endothelial function.” J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Aug 15;48(4):715-20.

Rabinowitch, IM. “Clinical and Other Observations on Canadian Eskimos in the Eastern Arctic.” (PDF). Can Med Assoc J. 1936 May; 34(5): 487–501.

Siri-Tarino PW, et al. “Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Mar;91(3):535-46.

Steegmans PH, et al. “Low serum cholesterol concentration and serotonin metabolism in men.” BMJ. 1996 Jan 27;312(7025):221.

St-Onge MP, et al. “Fiber and Saturated Fat Are Associated with Sleep Arousals and Slow Wave Sleep.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2015 Jun 22.

Tikkanen MJ, et al. “Apolipoprotein E4 homozygosity predisposes to serum cholesterol elevation during high fat diet.” Arteriosclerosis. 1990 Mar-Apr;10(2):285-8.