Friday morning at the Nutritional Therapy Association Annual Conference, which also just happened to also be World Sleep Day, I gave a keynote presentation on the connection between sleep and health with a particular focus on autoimmune disease. I included a collection of statistics in my talk, sharing the exact increased risk for major chronic health conditions associated with insufficient sleep. I was seeking to shift perspective on sleep—numbers can be highly motivating and eye-opening—wanting to emphasize just how critical of an input sleep in on health. And, it felt important to summarize that information here too, because sleep is something that far too many of us put on the back-burner and sacrifice for just about every other aspect of life.

The body of scientific literature linking inadequate sleep, more technically called “short sleep”, with disease is vast, so vast that there’s now huge meta-analyses combining data from multiple studies to establish a statistically powerful link. There’s also a very broad collection of mechanistic studies exploring the cellular and molecular details of exactly why we need sleep and all the bad things that happen in our bodies when we don’t get enough of it. The benefit for us is that quantifying the role that sleep plays in disease is pretty easy: I can tell you exactly how much your risk for diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, cancer and autoimmune disease goes up if you don’t get enough sleep. This is also the body of scientific literature that the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society used to establish their guidelines and the consensus statement, published just last year:

“Adults should sleep 7 or more hours per night on a regular basis to promote optimal health. Sleeping less than 7 hours per night on a regular basis is associated with adverse health outcomes, including weight gain and obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and stroke, depression, and increased risk of death. Sleeping less than 7 hours per night is also associated with impaired immune function, increased pain, impaired performance, increased errors, and greater risk of accidents.”

The National Sleep Foundation also recommends that adults between the ages of 18-64 prioritize 7-9 hours of sleep every single night. And I think this consistent recommendation from three reputable agencies is deserving of some contemplation. As members of the Paleo community and, more broadly, the alternative health community, we are used to thinking in terms of going beyond the minimums established by conventional medical and scientific communities. For example, we strive to regulate our blood sugars so perfectly that we have an even lower HbA1C than what is considered normal; we understand that optimal range is different than lab range for a variety of tests; and, we understand the RDA is likely a gross underestimate of how much essential nutrients we need to be optimally healthy (as opposed to just not completely malnourished). The conventional medical and scientific communities are shouting from every megaphone that we need a bare minimum of 7 hours of sleep every single night. Not only are we not doing our normal one-upping thing and saying “oh yeah? Well, we’re going to get a minimum of 8 hours per night, so there!”, but we’re not even listening at all!

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

The Dire Situation of Sleep in Western Countries

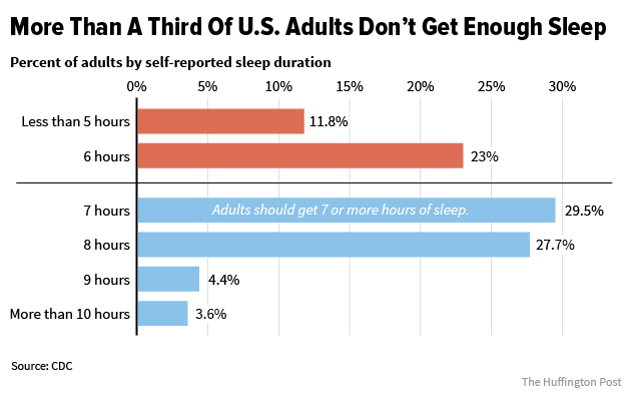

The fact is that 35% of Americans don’t ever get 7 hours of sleep. 65% of Americans never get 8 hours of sleep. And, however much sleep you think you’re getting, you’re very likely getting less.

The fact is that 35% of Americans don’t ever get 7 hours of sleep. 65% of Americans never get 8 hours of sleep. And, however much sleep you think you’re getting, you’re very likely getting less.

Most of us overestimate how much sleep we get. We look at the clock when we turn out the light and think of that as the beginning of our sleep. But, it’s normal to take 30-60 minutes to fall asleep. And, it’s normal to have at least a few brief wakings in the night. When we simply look at the clock at the beginning of the night versus the morning, we think of that as how much we slept.

Studies that have compared how individuals report their sleep with how much they actually slept measured by wrist actigraphy (like a Fitbit) and have found that on average, we report that we got 48 minutes more sleep than we actually did. But, here’s where things get interesting: the less you sleep, the more likely you are to overreport your sleep. So, people who got 5 hours of sleep per night on average overreported by 1 hour and 20 minutes (so, they said they got 6.3 hours instead of 5) and people who got 7 hours of sleep only overreported by 20 minutes. What does this mean? That if you get 6 hours or less, chances are good that your sleep situation is worse than you think.

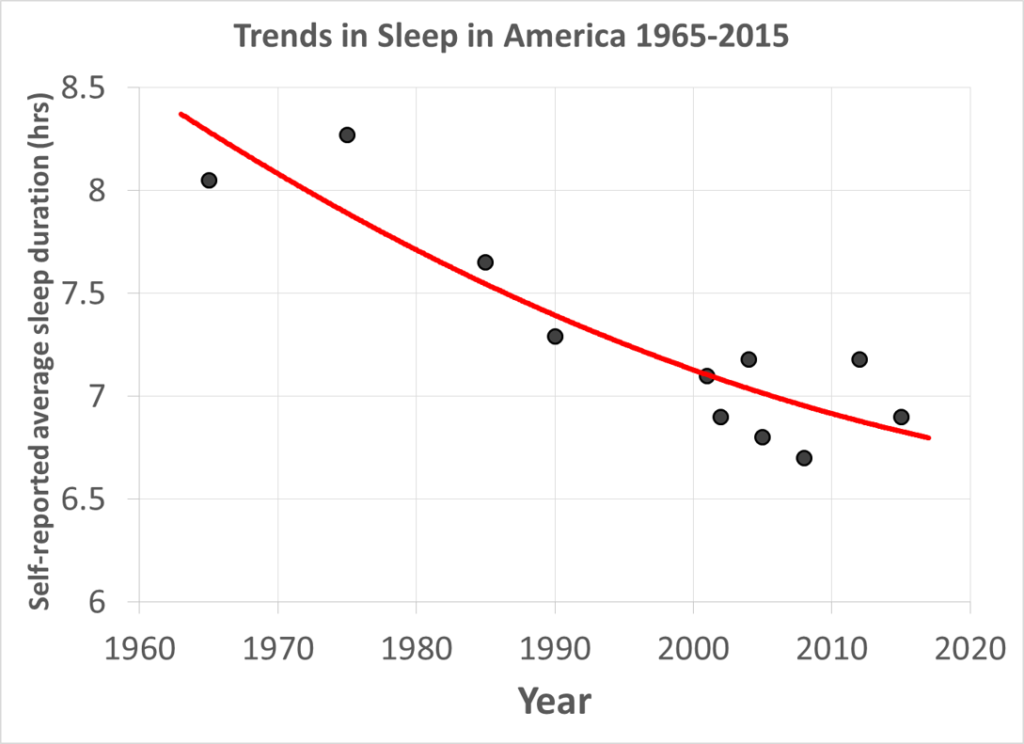

And, self-reported sleep is used to estimate how much sleep Americans are getting! Compared to 50 years ago, when the average sleep was about 8 hours per night, now we’re averaging about 6.9 hours per night. In 50 years, we went from the Gold Standard of Sleep as our average to less than the minimum required to preserve health. This is a huge contributor to the rise in chronic health problems seen over that same time period. And, as much as we want to blame the high PUFA, high refined-carbohydrate, processed food chemical-laden modern food supply, sleep is just as big, if not a bigger, culprit… one that deserves more airtime.

And, self-reported sleep is used to estimate how much sleep Americans are getting! Compared to 50 years ago, when the average sleep was about 8 hours per night, now we’re averaging about 6.9 hours per night. In 50 years, we went from the Gold Standard of Sleep as our average to less than the minimum required to preserve health. This is a huge contributor to the rise in chronic health problems seen over that same time period. And, as much as we want to blame the high PUFA, high refined-carbohydrate, processed food chemical-laden modern food supply, sleep is just as big, if not a bigger, culprit… one that deserves more airtime.

Sleep and All-Cause Mortality

One of the scientific strategies for quantifying how a factor impacts health is to look at something called all-cause mortality. Large cohorts of people are followed for years (sometimes decades) and every death is logged. Then, scientists can compare how many people died in each category of the factor being evaluated. In the instance of sleep, these studies tend to define short sleep as less than 6 hours per night, normal sleep as 6 to 9 hours per night, and long sleep as over 9 hours per night. Some studies look at narrower ranges, for example <5 hours, 6, hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, 9 hours, >10 hour. Comparing the number of deaths in each category gives us an indication of how sleep affects health. Yes, the number of deaths include deaths as a result of acute illness, chronic disease, old age, and accidental death. However, when you look at this number as a whole, it’s a very good way to measure overall health and longevity. More sophisticated statistics can account for other known health inputs such as smoking, being overweight, and activity level to hone in on the effect of sleep independent of other risk factors..

A 2010 meta-analysis pooled data from 27 different cohorts and found that sleeping less than 6 hours per night increased risk of all-cause mortality by 12%. To compare, being obese increases risk of all-cause mortality by 18%. Smoking about doubles risk of all-cause mortality. For every hour of physical activity that replaces sedentary time, risk of all-cause mortality drops by 16%. And ,for every daily serving of vegetables (up to 5 servings), risk of all-cause mortality drops by 5%.

Using all-cause mortality as an indicator, the health impact of getting less than 6 hours of sleep per night is in the same ballpark as being obese, being sedentary, and not eating many vegetables. But, here’s where things get interesting. Getting less than 6 hours of sleep per night also increases the chances of being obese, being inactive, and not eating many vegetables. So, not only is not getting enough sleep an independent risk factor for disease, but then the probability of having additional risk factors goes up! In the Paleo community, we are focused on the healthiest diet choice, activity, and maintaining a healthy weight. We need to add consistently getting 7-8 hours of sleep to this list of Paleo priorities. And guess what? Not only will that make us healthier, but being well rested makes making healthy food choices easier, increases our motivation to move, and directly affects hunger and metabolism, major contributors to body weight.

Sleep and Obesity

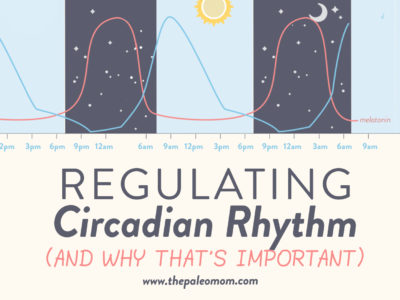

Sleeping less than 6 hours per night increases risk of obesity by 55% in adults (90% in children!). But, when it comes to obesity, researchers have teased out some other fascinating links between how we sleep and obesity risk. Variability in bedtime during the week >2 hours increases risk of obesity by 14%. That means that if you normally go to bed at 10pm on weeknights and stay up until midnight Saturday for a party, your risk of obesity is higher. This is such a normal pattern for students and working adults alike! Sleep duration variability increases risk of obesity 63% increase for each 1 hour of standard deviation. That means that if some nights you gets 6 hours and other nights you try to make up for it and sleep 9 hours, that inconsistency is dramatically increasing risk of obesity! It’s also important to sync our sleep time with the sun: following the night owl patterns of late-to-bed, late-to-rise doubles risk of obesity compared to early-to-bed, early-to-rise, even in people who get enough sleep!

Sleeping less than 6 hours per night increases risk of obesity by 55% in adults (90% in children!). But, when it comes to obesity, researchers have teased out some other fascinating links between how we sleep and obesity risk. Variability in bedtime during the week >2 hours increases risk of obesity by 14%. That means that if you normally go to bed at 10pm on weeknights and stay up until midnight Saturday for a party, your risk of obesity is higher. This is such a normal pattern for students and working adults alike! Sleep duration variability increases risk of obesity 63% increase for each 1 hour of standard deviation. That means that if some nights you gets 6 hours and other nights you try to make up for it and sleep 9 hours, that inconsistency is dramatically increasing risk of obesity! It’s also important to sync our sleep time with the sun: following the night owl patterns of late-to-bed, late-to-rise doubles risk of obesity compared to early-to-bed, early-to-rise, even in people who get enough sleep!

Sleep and Type 2 Diabetes

Sleeping less than 6 hours per night increases risk of type 2 diabetes by 50%. But, if you pool diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance together, that risk soars to a whopping 2.4 times! The link between sleep and insulin sensitivity is very strong. In fact, there’s studies where participants are only allowed 4-5 hours’ sleep per night and develop glucose intolerance within a few days! What might be even more fascinating is that there’s emerging evidence that the impact of sleep on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism is even greater than diet. Research presented at last fall’s Obesity Society Annual Meeting shows that a single night of lost sleep was worse than six months of a high-fat Western diet in terms of insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism!

Sleeping less than 6 hours per night increases risk of type 2 diabetes by 50%. But, if you pool diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance together, that risk soars to a whopping 2.4 times! The link between sleep and insulin sensitivity is very strong. In fact, there’s studies where participants are only allowed 4-5 hours’ sleep per night and develop glucose intolerance within a few days! What might be even more fascinating is that there’s emerging evidence that the impact of sleep on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism is even greater than diet. Research presented at last fall’s Obesity Society Annual Meeting shows that a single night of lost sleep was worse than six months of a high-fat Western diet in terms of insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism!

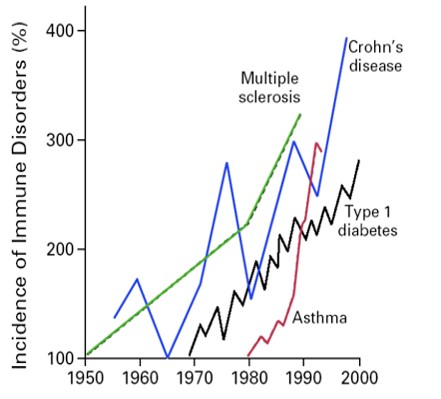

Sleep and Autoimmune Disease

Research into risk factors for autoimmune disease is still in its infancy. There have yet to be any large population studies looking at average sleep duration and autoimmune disease incidence. However, having a non-apnea related sleep disorder (the most common of which is insomnia, which can be as mild as having a night or two a week where either you can’t fall asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep) increases risk of autoimmune disease on average by 50%! Some autoimmune disease incidence is more sensitive to non-apnea sleep disorders that others. For example, the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus goes up 81%, rheumatoid arthritis risk goes up 45%, ankylosing spondylitis risk goes up 53%, and Sjögren’s syndrome risk goes up 51%. It’s even worse if you suffer from obstructive sleep apnea, a condition that tends to go along with obesity and diabetes, which more than doubles risk of autoimmune disease. Shift workers, known for having erratic sleep schedules and routinely getting inadequate sleep, have a 50% higher risk of autoimmune disease. It’s also known that short sleep increases symptoms of many autoimmune diseases.

Research into risk factors for autoimmune disease is still in its infancy. There have yet to be any large population studies looking at average sleep duration and autoimmune disease incidence. However, having a non-apnea related sleep disorder (the most common of which is insomnia, which can be as mild as having a night or two a week where either you can’t fall asleep or you wake up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep) increases risk of autoimmune disease on average by 50%! Some autoimmune disease incidence is more sensitive to non-apnea sleep disorders that others. For example, the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus goes up 81%, rheumatoid arthritis risk goes up 45%, ankylosing spondylitis risk goes up 53%, and Sjögren’s syndrome risk goes up 51%. It’s even worse if you suffer from obstructive sleep apnea, a condition that tends to go along with obesity and diabetes, which more than doubles risk of autoimmune disease. Shift workers, known for having erratic sleep schedules and routinely getting inadequate sleep, have a 50% higher risk of autoimmune disease. It’s also known that short sleep increases symptoms of many autoimmune diseases.

Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease

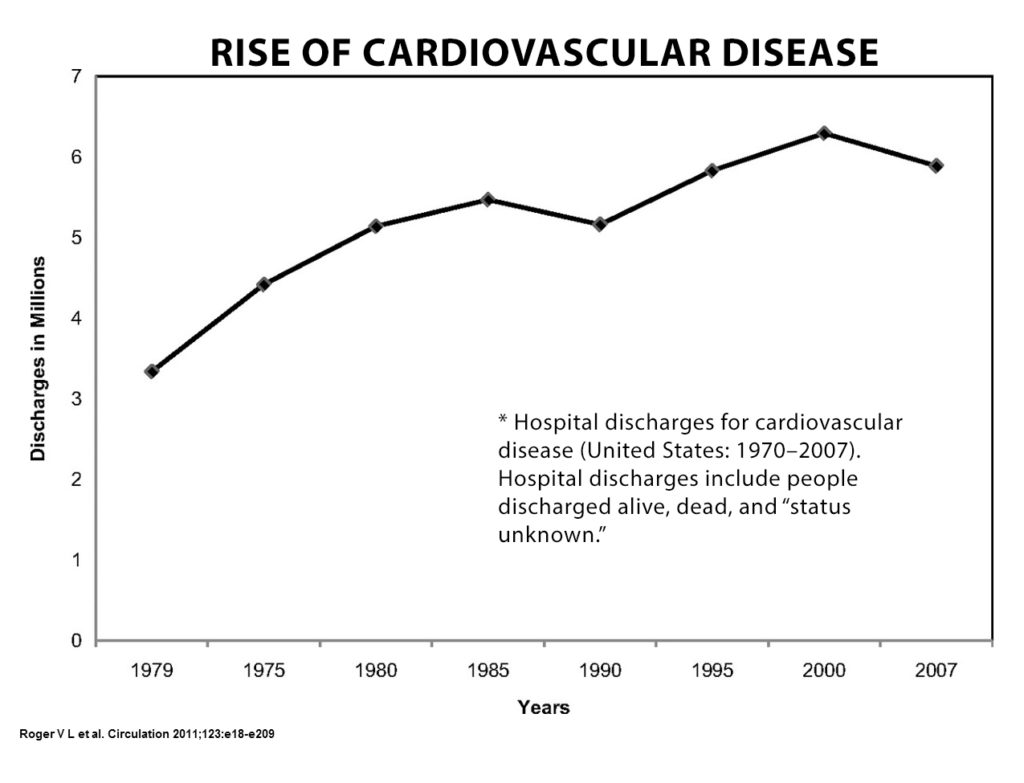

Routinely sleeping less than 6 hours per night compared to getting between 6 and 8 hours every night double risk of stroke, doubles risk of myocardial infarction, increases risk of congestive heart failure by 67%, and increases risk of coronary heart disease by 48%. Those are huge numbers! And it’s worth adding the comment here that we are so quick to blame diet factors for the dramatic increase in cardiovascular disease seen over the last 50 years. In the 70s and 80s, saturated fat and cholesterol were to blame. Now, it’s high fructose corn syrup, PUFAs, and processed food chemicals. I certainly believe that diet is a factor here, but when you look at the body of literature explaining how inadequate sleep raises LDL cholesterol, raises blood pressure, increases heart rate variability and causes inflammation, I think there may be a bigger fish to fry (in non-hydrogenated oil, of course!).

Routinely sleeping less than 6 hours per night compared to getting between 6 and 8 hours every night double risk of stroke, doubles risk of myocardial infarction, increases risk of congestive heart failure by 67%, and increases risk of coronary heart disease by 48%. Those are huge numbers! And it’s worth adding the comment here that we are so quick to blame diet factors for the dramatic increase in cardiovascular disease seen over the last 50 years. In the 70s and 80s, saturated fat and cholesterol were to blame. Now, it’s high fructose corn syrup, PUFAs, and processed food chemicals. I certainly believe that diet is a factor here, but when you look at the body of literature explaining how inadequate sleep raises LDL cholesterol, raises blood pressure, increases heart rate variability and causes inflammation, I think there may be a bigger fish to fry (in non-hydrogenated oil, of course!).

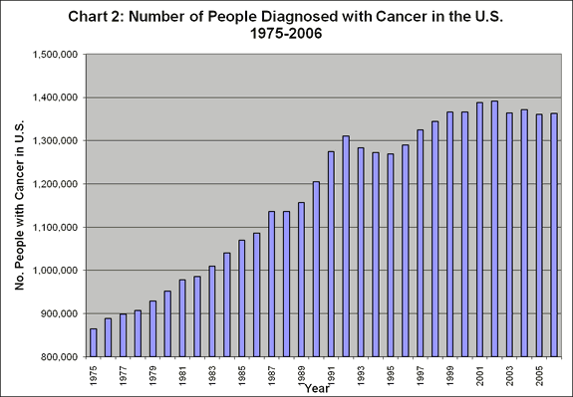

Cancer

Finally, some less than morbidly bleak news. In the studies that have looked at prostate, breast and lung cancer, there was no increased risk with short sleep even comparing people who get under 5 hours of sleep per night to those who get 7-8 hours. The exception is studies of colorectal adenoma, in which the risk increases by 50% with less than 5 hours of sleep. However, how much sleep you get upon and after breast cancer diagnosis is a predictor of survival, and getting less than 6 hours of sleep increases risk of death by 46%.

Finally, some less than morbidly bleak news. In the studies that have looked at prostate, breast and lung cancer, there was no increased risk with short sleep even comparing people who get under 5 hours of sleep per night to those who get 7-8 hours. The exception is studies of colorectal adenoma, in which the risk increases by 50% with less than 5 hours of sleep. However, how much sleep you get upon and after breast cancer diagnosis is a predictor of survival, and getting less than 6 hours of sleep increases risk of death by 46%.

Sleeping Too Much?

This is all pretty bad news for people who have difficulty carving out enough time for sleep in their lives. But, the coin does have a flip side. There’s a collection of studies showing increased disease risk in long sleepers. A large meta-analysis looking at all-cause mortality showed 25% higher risk for those sleeping more than 9 hours per night (compared to 7-8 hours) and a 54% higher risk for those sleeping more than 10 hours. However, there’s a chicken versus egg discussion to engage in here. Are people sleeping more because they’re sick or are they sick because they’re sleeping more? A recent study evaluated the effect of sleep on survival rate in groups with different levels of physical activity and found that long sleep, more than 9 hours, only increased all-cause mortality in physically inactive people.

And when the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society reviewed the scientific literature on this topic, they came up with the following for their consensus statement:

“Sleeping more than 9 hours per night on a regular basis may be appropriate for young adults, individuals recovering from sleep debt, and individuals with illnesses. For others, it is uncertain whether sleeping more than 9 hours per night is associated with health risk.”

Take home Message

As you can see, the consequences of inadequate sleep is far more dire than simply walking around feeling like a zombie the next day. Sleep isn’t just important, it’s critical for health! And, there’s no substitute. This isn’t like outdoors time where we can take a vitamin D3 supplement and use a light therapy box for circadian rhythm entrenchment and suffer no ill effects from a life spent indoors. Coffee, energy drinks and supplements just mask the fatigue, give the illusion that everything’s fine, and then erode sleep quality the next night. They are crutches, and they don’t provide our bodies with any tangible support other than to allow us to continue to ignore our body’s signals and abuse our bodies through neglect.

As you can see, the consequences of inadequate sleep is far more dire than simply walking around feeling like a zombie the next day. Sleep isn’t just important, it’s critical for health! And, there’s no substitute. This isn’t like outdoors time where we can take a vitamin D3 supplement and use a light therapy box for circadian rhythm entrenchment and suffer no ill effects from a life spent indoors. Coffee, energy drinks and supplements just mask the fatigue, give the illusion that everything’s fine, and then erode sleep quality the next night. They are crutches, and they don’t provide our bodies with any tangible support other than to allow us to continue to ignore our body’s signals and abuse our bodies through neglect.

And, this is why I created Go To Bed: 14 Easy Steps to Healthier Sleep. The single best thing that we can do to improve our sleep is to take our bodies, put them into our beds, turn out the lights, turn off the TV, and close our eyes. But, there’s also A LOT more to ensuring that we get the best quality sleep possible, that our bodies will cooperate when we put them to bed and sleep restoratively. All of the detailed science explaining the links between sleep and health are discussed, every scientifically-validated strategy to improve sleep, plus tons of practical tips to help you inch sleep higher up on the priority list. And, Go To Bed includes a 14-Day step-by-step challenge geared at getting you implementing the most effective strategies to get healthier sleep in the easiest, most painless, most supported, and most engaging way possible. If you don’t have it yet, you can read more about it here.

And, this is why I created Go To Bed: 14 Easy Steps to Healthier Sleep. The single best thing that we can do to improve our sleep is to take our bodies, put them into our beds, turn out the lights, turn off the TV, and close our eyes. But, there’s also A LOT more to ensuring that we get the best quality sleep possible, that our bodies will cooperate when we put them to bed and sleep restoratively. All of the detailed science explaining the links between sleep and health are discussed, every scientifically-validated strategy to improve sleep, plus tons of practical tips to help you inch sleep higher up on the priority list. And, Go To Bed includes a 14-Day step-by-step challenge geared at getting you implementing the most effective strategies to get healthier sleep in the easiest, most painless, most supported, and most engaging way possible. If you don’t have it yet, you can read more about it here.

Citations

Aggarwal S, et al “Associations between sleep duration and prevalence of cardiovascular events.” Clin Cardiol. 2013 Nov;36(11):671-6. doi: 10.1002/clc.22160. Epub 2013 Oct 1.

Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. “Sleep duration affects risk for ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study.” Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Nov;12(11):1879-86. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.021. Epub 2014 Apr 26.

Bailey, BW (2014) Objectively Measured Sleep Patterns in Young Adult Women and the Relationship to Adiposity. American Journal of Health Promotion: September/October 2014, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 46-54.

Bellavia A, et al. “Sleep duration and survival percentiles across categories of physical activity.” Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Feb 15;179(4):484-91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt280. Epub 2013 Nov 20.

Broussard J. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Poster abstract presentation at: The Obesity Society Annual Meeting at ObesityWeekSM 2015; November 2-6, 2015; Los Angeles, CA. www.obesityweek.com.

Cappuccio, FP, et al. “Meta-Analysis of Short Sleep Duration and Obesity in Children and Adults” Sleep. 2008 May 1; 31(5): 619–626.

Cappuccio, FP et al “Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies” Sleep. 2010 May 1; 33(5): 585–592.

Cappuccio FP, et al. “Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies.” Eur Heart J. 2011 Jun;32(12):1484-92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. Epub 2011 Feb 7.

Chaput JP, et al. “Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance: analyses of the Quebec Family Study.” Sleep Med. 2009 Sep;10(8):919-24. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.09.016. Epub 2009 Mar 29.

Cutolo M, et al. “Altered circadian rhythms in rheumatoid arthritis patients play a role in the disease’s symptoms.” Autoimmun Rev. 2005 Nov;4(8):497-502. Epub 2005 Jun 13. Review.

Ekelund U, et al. “Physical activity and all-cause mortality across levels of overall and abdominal adiposity in European men and women: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study (EPIC).” Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Mar;101(3):613-21. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100065. Epub 2015 Jan 14.

Flegal KM, et al. “Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA. 2013 Jan 2;309(1):71-82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905.

Ford ES. “Habitual sleep duration and predicted 10-year cardiovascular risk using the pooled cohort risk equations among US adults.” J Am Heart Assoc. 2014 Dec 2;3(6):e001454. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001454.

Gangwisch JE, et al “Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large U.S. sample.” Sleep. 2007 Dec;30(12):1667-73.

Gooley. JJ. “How Much Day-To-Day Variability in Sleep Timing Is Unhealthy?” SLEEP, 2016; 39 (02): 269

Hsiao YH, et al. “Sleep disorders and increased risk of autoimmune diseases in individuals without sleep apnea.” Sleep. 2015 Apr 1;38(4):581-6. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4574.

Jones MR, et al. “Smoking, menthol cigarettes and all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular mortality: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and a meta-analysis.” PLoS One. 2013 Oct 25;8(10):e77941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077941. eCollection 2013.

Kang JH, Lin HC. “Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of autoimmune diseases: a longitudinal population-based study.” Sleep Med. 2012 Jun;13(6):583-8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.03.002. Epub 2012 Apr 21.

Kobayashi D, et a. “High sleep duration variability is an independent risk factor for weight gain.” Sleep Breath. 2013 Mar;17(1):167-72. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0665-7. Epub 2012 Feb 22.

Lauderdale, DS, et al. “Sleep duration: how well do self-reports reflect objective measures? The CARDIA Sleep Study” Epidemiology. 2008 November; 19(6): 838–845.

Loprinzi PD. “Light-Intensity Physical Activity and All-Cause Mortality.” Am J Health Promot. 2016 Jan 5. [Epub ahead of print]

Lu Y, et al. “Association between sleep duration and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.” PLoS One. 2013 Sep 4;8(9):e74723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074723. eCollection 2013.

Phipps A, et al. “Prediagnostic Sleep Duration and Sleep Quality in Relation to Subsequent Cancer Survival.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2015 Nov 19. pii: jc-00337-15. [Epub ahead of print]

Roehrs TA, et al. “Pain sensitivity and recovery from mild chronic sleep loss.” Sleep. 2012 Dec 1;35(12):1667-72. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2240.

Taylor, BJ, et al. “Bedtime Variability and Metabolic Health in Midlife Women: The SWAN Sleep Study”. SLEEP, 2016; 39 (02): 457

Thompson CL, et al. “Short duration of sleep increases risk of colorectal adenoma.” Cancer. 2011 Feb 15;117(4):841-7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25507. Epub 2010 Oct 8.

Wang X, et al, “Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.” BMJ. 2014 Jul 29;349:g4490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4490.

Watson NF, et al “Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society”. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(6):591–592.

Wu Y, et al. “Sleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies.” Sleep Med. 2014 Dec;15(12):1456-62. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.018. Epub 2014 Sep 28.

Yaggi HK, et al. “Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes.” Diabetes Care. 2006 Mar;29(3):657-61.

Zhao H, et al. “Sleep duration and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies.” Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(12):7509-15.