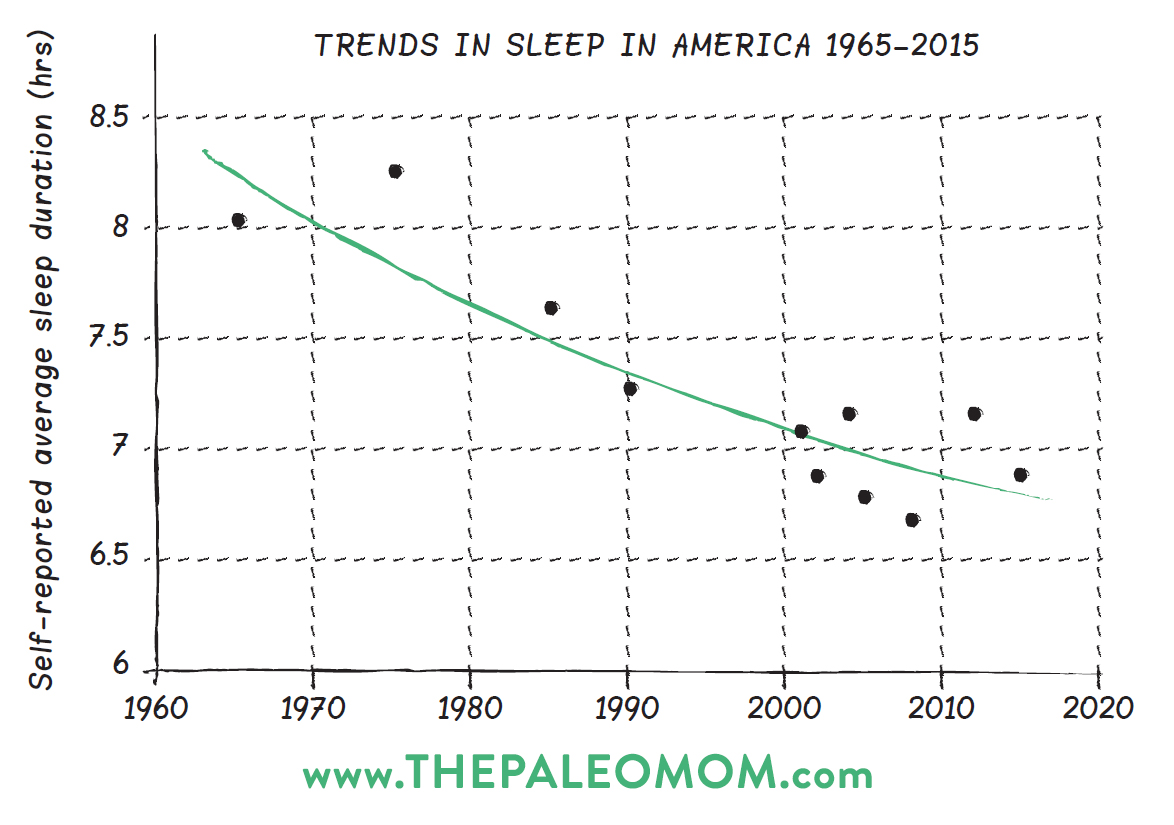

I’ve very passionate about the necessity of sleep for health, which is why I wrote an entire online sleep program called Go To Bed: 14 Steps to Healthier Sleep. In the last 50 years, the average amount of time that Americans sleep each night has decreased by 1.5–2 hours. That’s a staggering amount of sleep—equivalent to a full month of continuous sleep every year—that we need but are not getting. From what we know about how lack of sleep affects our brains, hormones, and immune system, this may be the single greatest contributor to chronic illness in general. That’s right, sleep, and not diet. Not activity level. Not stress. Sleep.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

Epidemiological studies show a very strong correlation between short or disturbed sleep and obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In fact, lack of adequate sleep has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality from all causes. This means that if you consistently don’t get enough sleep, you have a much higher risk of getting sick and/or dying. Period. Studies have also evaluated the role that sleep plays in healing from specific diseases, like breast cancer, and show that the less you sleep, the less likely you are to survive. See Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!, The Link Between Sleep and Your Weight, and 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food.

Even more compelling, mechanistic studies explaining exactly how sleep, or lack thereof, affects our body at the cellular and molecular level are showing us exactly why sleep is so important for health. In fact, as our scientific understanding of exactly how sleep impacts health increases, the stronger the case for sleep being the lynchpin of health. See The New Science of Sleep-Wake Cycles (and How to Improve Yours!)

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

But how much sleep do we need? What exactly constitutes a sleep debt? How little sleep can we get away with before we start to see an impact on our health?

How Much Sleep Do We Need?

The National Sleep Foundation recently convened experts from sleep, anatomy and physiology, as well as pediatrics, neurology, gerontology and gynecology to reach a consensus from the broadest range of scientific disciplines. The panel revised the recommended sleep ranges and came up with these guidelines:

| Newborns (0-3 months) | 14-17 hours |

| Infants (4-11 months) | 12-15 hours |

| Toddlers (1-2 years) | 11-14 hours |

| Preschoolers (3-5) | 10-13 hours |

| School age children (6-13) | 9-11 hours |

| Teenagers (14-17) | 8-10 hours |

| Younger adults (18-25) | 7-9 hours |

| Adults (26-64) | 7-9 hours |

| Older adults (65+) | 7-8 hours |

If you are trying to heal from an autoimmune disease, don’t be surprised if what your body needs is on the longer end of that range (say 9 to 10 hours) or even exceeding that range (some people with autoimmune disease report needing 12 hours of sleep every night to heal). I believe even grown-ups need bedtimes. By making sure yours in early enough to hit 7 hours of sleep every night, you’ll be greatly improving your health and reducing risk of all chronic illnesses. See also How Much Sleep Do We Need? Understanding the Hunter-Gatherer Evidence

Sleep Debt

Sleep Debt

Defining how much sleep you need within the normal ranges can be a challenge. Do you enjoy perfect health with 7 hours every night? Or do you need 9 hours on a regular basis? And what if you’re someone who needs more sleep than the top end of the range (which happens during either chronic or acute illness)? How do you know? While scientific researchers are indeed working on a blood test to evaluate sleep debt (serum levels of oxalic acid and diacylglycerol 36:3), being able to ask your doctor to run a test that will tell you if you’re getting enough sleep is probably at least a few years from being a reality.

In the absence of a definitive test, you can ask yourself the following questions:

- Do I have to set an alarm in the morning? Would I sleep past my alarm time if I didn’t have one set?

- Do I drag myself out of bed? Or need caffeine in the morning to get me going?

- Do I always sleep in on the weekends?

- Do I get less than the minimum 7 hours sleep per night even once or twice per week?

If the answer is “yes” to any of these questions, you owe a sleep debt. And even if you’re almost getting the right amount of sleep, i.e., your sleep debt is very low, your health will suffer. A recent study showed that getting just 30 minutes less sleep per night than your body needs on weekdays (while sleeping in on weekends) can have long-term consequences for body weight and metabolism! See also Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies! and 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food

Most research into the role that sleep has on health uses “short sleep” as an investigatory tool. Short sleep means sleep that is restricted to a shorter duration than you would normally get (typically 3-5 hours is used in short sleep studies). However, as researchers start to look at sleep dept instead of more dramatic situations, it’s becoming clear just how sensitive the human body is to inadequate sleep.

In this case, the study participants kept sleep logs, and the researchers calculated how much less sleep they got than the recommended 8 hours a night cumulative over the workweek (not including sleeping in to “catch up on sleep” on the weekends). The study participants were people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. They were randomized into one of three groups: usual care, physical activity intervention, or diet and physical activity intervention. When the participants were recruited, those that typically didn’t get enough sleep were 72% more likely to be obese. The researchers then followed the participants over a year to see what would change. Note that addressing sleep was not part of any of the study interventions. The amount of sleep dept that individuals had didn’t typically change during the study.

Sleep debt dramatically impacted risk of obesity and insulin resistance, and the correlation between the two increased throughout the study. At 12 months, for every 30 minutes of weekday sleep debt, the risk of obesity was 17% higher and the risk of insulin resistance 39% higher. Think about that for a second. If you get 30 minutes less sleep a night than you need just on week days, you have a 39% higher risk of insulin resistance. If you get an hour less sleep a night, you have a 78% higher risk. A separate study showed that some components of the immune system that become overactive during short sleep (Th17 cells) do not return to normal after two days of sleeping in. Combined, these studies tell us that we need to get enough sleep every single night. See also The Link Between Sleep and Your Weight

Now, this study was done in a population that is much higher risk of developing these conditions than the average Paleo dieter. But, when you combine this with the huge collection of mechanistic studies showing that inadequate sleep increases insulin resistance, causes cortisol secretion, causes toxins to build up in our brains, causes neurotransmitter imbalances, stimulates the immune system and is inflammatory, and causes increased hunger and cravings… this isn’t research that should be dismissed.

Take-home Message: Not getting enough sleep is detrimental to our health. The effects are additive. You can’t catch up on weekends (there’s other studies that show this too, especially in terms of the effects of sleep on the immune system). Our bodies are very sensitive to sleep deprivation. Much more sensitive than we’ve ever previously thought.

If you’re looking to optimize your sleep, check out my online sleep program Go To Bed: 14 Steps to Healthier Sleep

Citations

Bosy-Westphal, A., et al., “Influence of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance and insulin sensitivity in healthy women”, Obes Facts. 2008;1(5):266-73

Hirshkowitz, M et al. “National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary.” Sleep Health, 2015;1(1):40-43