There are many topics that I am researching and writing about for the book that I’ve been meaning to write about for the blog for ages (the book just gives me a firm deadline). I have decided take some of these topics (especially the more blog-sized ones) and publish them as teaser excerpts for the book (also because I think this information should be here too).

There are many topics that I am researching and writing about for the book that I’ve been meaning to write about for the blog for ages (the book just gives me a firm deadline). I have decided take some of these topics (especially the more blog-sized ones) and publish them as teaser excerpts for the book (also because I think this information should be here too).

The book also contains a detailed (yet easy-to-follow) description of the components of the immune system, including a great quick reference guide to help you as you read through the book. So, when you read this section in the book, you’ll already know why modulating Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells is important and you’ll already understand the essential role that regulatory T-cells play in the immune system.

For a quick primer: Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells are subtypes of lymphocytes (white blood cells) that can be over-activated in autoimmune disease and cause damage. Regulatory T-cells are another subtype of lymphocyte that are supposed to keep all the other immune cells in check and suppress both over-activation of the immune system and autoimmunity (they tend to be deficient in autoimmune disease). Cytokines are chemical messengers of inflammation. Monocytes and neutrophils are types of white blood cell responsible for generalized inflammation (part of the innate immune system whereas B-cells and T-cells are part of the adaptive immune system). B-cells are the type of lymphocyte that produce antibodies.

So, forgive the references to Chapter 7 and page numbers with no number. While you’ll have to wait until the book is out to read those sections, in the meantime, please enjoy this part of Chapter 4: Lifestyle Factors That Contribute to Autoimmune Disease.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

Excited to read The Paleo Approach?

Want to help spread the word about my book? Please share this post and other teaser excerpts. Thank you!

“A good laugh and a long sleep are the best cures in the doctor’s book.”

–Irish Proverb

In the last 50 years, the average amount of time that Americans sleep each night has decreased by 1.5–2 hours. That’s a staggering amount of sleep—equivalent to a full month of continuous sleep every year—that we need but are not getting. Epidemiological studies show a strong correlation between short or disturbed sleep and obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In fact, lack of adequate sleep has been associated of increased morbidity and mortality from all causes. This means that if you consistently don’t get enough sleep, you have a much higher risk of getting sick and/or dying. Period. Studies have also evaluated the role that sleep plays in healing from specific diseases, like breast cancer, and show that the less you sleep, the less likely you are to survive.

Frankly, scientists still don’t really understand why we need sleep, why we need as much as we do, and what our bodies are actually doing while we sleep. But, it is obvious that sleep is important for human health. Studies that evaluate the physiological changes caused by not sleeping or not getting enough sleep can be very instructive in understanding just how critically important sleep is. For those with autoimmune disease, it is especially important to understand the role that sleep has in inflammation, stimulating the immune system, and regulating hormones (which themselves modulate the immune system).

Just plain old not getting enough sleep causes inflammation even in young, healthy people. A variety of studies evaluating the effects of acute sleep deprivation (typically by restricting sleep to 4 hours per night) for several consecutive days (typically 3 to 5) have shown increases in markers of inflammation and the numbers of white blood cells in the blood. Specifically, even just three consecutive nights of not enough sleep can cause increased monocytes, neutrophils and B-cells in the blood, increased proinflammatory cytokines (including cytokines known to stimulate maturation of naïve T-cells into Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells), increased C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), increased total cholesterol and increased low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL).

Even just one night of lost sleep (40 hours without sleep) causes inflammation in young, healthy people. Just pulling a single all-nighter dramatically increases markers of inflammation in the blood, including C-reactive protein and proinflammatory cytokines. Studies that evaluated not just sleep deprivation but also recovery after sleep restriction (with the idea of simulating a typical workweek where someone might get less sleep for 4 or 5 nights straight and then try to make up for it on the weekend) have also shown that the proinflammatory cytokine known to stimulate Th17 cell development persists for at least two days after increasing sleep to 8 hours per night, even though other markers of inflammation have recovered. This means that even if you try and “catch up” on your sleep during the weekend, the stimulation to the immune system keeps going. If you follow this stereotypical pattern of not getting enough sleep during the week and sleeping in on the weekend, you still run the risk of cumulatively causing detrimental changes in the immune system. Certainly, you can recover from lack of sleep, but it takes persistence, consistency and commitment—even during the week.

Sleep deprivation is also associated with increased susceptibility to infection. In fact, the less sleep you get, the more likely you are to catch the common cold. Getting adequate sleep can also protect you from infection. One study even showed that the longer the sleep duration, the lower the incidence of parasitic infections in mammals.

Inadequate sleep also has profound effects on hunger hormones and metabolism (recall that hunger hormones such as insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol are important modulators of the immune system, see page ##, ## and ##). For example, when food intake is measured following sleep deprivation (5 consecutive days of 4 hours sleep), people tend to eat substantially (20%!) more than normal. However, it doesn’t take five full days of inadequate sleep to see dramatic effects on insulin, cortisol, and leptin. One study showed that even a single night of partial sleep (4 hours) causes insulin resistance in healthy people. Another study showed that a single night of partial sleep (3 hours, in this case) caused reduced morning cortisol levels (when cortisol should be its highest) and elevated afternoon/evening cortisol (when cortisol should be gradually decreasing) and elevated morning leptin levels. This means that one night of three or four hours sleep causes insulin resistance, dysregulated cortisol and increased leptin. One late bedtime because you went to a late night movie or a party at the boss’ house. One.

Inadequate sleep has also been investigated as a possible cause of autoimmune disease. In an animal model of psoriasis, sleep deprivation caused significant increases in proinflammatory cytokines, cortisol levels, and increases in specific proteins in the skin associated with symptoms of psoriasis (like the flaking, dry, scaly skin). In an animal model of multiple sclerosis, mice subjected to sleep deprivation developed the disease earlier than mice that slept normally. Once the mice developed multiple sclerosis, sleep deprivation caused increased disease activity and pain sensitivity. Furthermore, sleep disturbances are commonly reported by people with chronic inflammatory conditions (such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease and asthma). Whether the sleep disturbances cause the disease or the disease causes the sleep disturbances is not well understood. However, such sleep disturbances are known to worsen the course of the disease, aggravate disease symptoms such as pain and fatigue, increase disease activity and lower quality of life. Yes, sleep is important.

So, how much sleep do you need? There is no clear answer to this. Consensus is that healthy adults need 7-10 hours of sleep per night. If you are trying to heal from an autoimmune disease, don’t be surprised if what your body needs is on the longer end of that range (say 9 to 10 hours) or even exceeding that range (some people with autoimmune disease report needing 12 hours of sleep every night to heal).

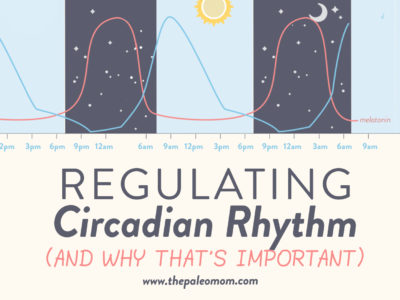

Getting enough sleep isn’t just about preventing inflammation; it’s also about repairing the body and modulating the immune system. Certainly, the process of tissue repair in the body is predominantly performed during sleep. However, an important study showed that regulatory T-cell activities follow a circadian rhythm, meaning that, just like many functions within the human body, they increase and decrease throughout the day. In healthy people, regulatory T-cells are highest in the blood at night with lowest numbers in the morning (similar to melatonin production and the opposite of cortisol). The activity of the regulatory T-cells also follows a circadian rhythm, having the highest suppressive activity during sleep and lowest in the morning. When volunteers were subjected to sleep deprivation, the suppressive activity of their regulatory T-cells was decreased (even though the actual numbers of T-cells remained the same). This implies that sleep is required for the suppressive activity of regulatory T-cells, meaning that if you want to modulate your immune system and reverse your autoimmune disease, sleep is critical.

If you have an autoimmune disease (I generally assume you do if you are reading this book) and aren’t getting 8 hours of good sleep every night, I cannot emphasize enough the importance of putting sleep on the top of your priority list. You need sleep. Now. Tonight. Every night. Seriously, stop reading and go to bed. Strategies for prioritizing sleep and what to do if you are trying to get more sleep but just can’t are discussed in Chapter 7.

Interested in learning even more about The Paleo Approach? This video from my YouTube Channel is just a quick tour (the book is so big that giving you a broad overview takes 13 minutes!) but you get to see just how comprehensive and detailed this book is.

Bollinger, T., et al., Sleep-dependent activity of T cells and regulatory T cells, Clin Exp Immunol. 2009 Feb;155(2):231-8

Bosy-Westphal, A., et al., Influence of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance and insulin sensitivity in healthy women, Obes Facts. 2008;1(5):266-73

Boudjeltia KZ, et al., Sleep restriction increases white blood cells, mainly neutrophil count, in young healthy men: a pilot study, Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(6):1467-70.

Donga, E., et al., A single night of partial sleep deprivation induces insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways in healthy subjects, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;95(6):2963-8.

Frey, D.J., et al., The effects of 40 hours of total sleep deprivation on inflammatory markers in healthy young adults, Brain Behav Immun. 2007 Nov;21(8):1050-7

Heslop, P., et al., Sleep duration and mortality: The effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in working men and women, Sleep Med. 2002 Jul;3(4):305-14.

Hirotsu, C., et al., Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis, PLoS One. 2012;7(11)

Lehrer S, et al., Insufficient sleep associated with increased breast cancer mortality, Sleep Med. 2013 Mar 4 pii: S1389-9457(12)00384-X. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.012. [Epub ahead of print]

Lucassen EA, et al., Interacting epidemics? Sleep curtailment, insulin resistance, and obesity, Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012 Aug;1264(1):110-34

Meier-Ewert HK, et al., Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk, J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Feb 18;43(4):678-83.

Palma, B.D., et al., Effects of sleep deprivation on the development of autoimmune disease in an experimental model of systemic lupus erythematosus, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006 Nov;291(5):R1527-32.

Palma, B.D. & Tufik, S., Increased disease activity is associated with altered sleep architecture in an experimental model of systemic lupus erythematosus, Sleep. 2010 Sep;33(9):1244-8.

Ranjbaran, Z., et al., The relevance of sleep abnormalities to chronic inflammatory conditions, Inflamm Res. 2007 Feb;56(2):51-7.

Reynolds AC, et al., Impact of five nights of sleep restriction on glucose metabolism, leptin and testosterone in young adult men, PLoS One. 2012;7(7)

van Leeuwen WM, et al., Sleep restriction increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases by augmenting proinflammatory responses through IL-17 and CRP, PLoS One. 2009;4(2)