Berries are an extremely ancient food in the human diet, with evidence of being a seasonal staple for prehistoric hunter-gatherers. And, science has given us plenty of reasons to keep eating them today! These nutrient-dense superfoods are linked with diverse health benefits, including reducing inflammation, lowering cardiovascular disease risk, lowering cancer risk, improved cognition, improved insulin sensitivity and serum glucose regulation, and improved gut health!

Berries are an extremely ancient food in the human diet, with evidence of being a seasonal staple for prehistoric hunter-gatherers. And, science has given us plenty of reasons to keep eating them today! These nutrient-dense superfoods are linked with diverse health benefits, including reducing inflammation, lowering cardiovascular disease risk, lowering cancer risk, improved cognition, improved insulin sensitivity and serum glucose regulation, and improved gut health!

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

From a botanical standpoint, berries are defined as any fruit produced from the ovary of a single flower, containing multiple seeds and fleshy pulp (or pericarp) that develops from the ovary wall. By that definition, berries include some surprising members (bananas, peppers, watermelon, eggplant, and pumpkin!) while excluding some we’d expect to see on the list (like blackberries, strawberries, and raspberries). But, most of us are much more familiar with the culinary definition: berries being any small, pulpy fruit with lots of little seeds. By that criteria, we end up with the following:

- Açaí berries, which are small, round, and dark purple, somewhat resembling a grape, and are a major staple of some traditional populations in the Brazilian Amazon

- Bilberries, which are a European relative of the blueberry

- Blackberries, which are sweet and tangy and deep purple; along with their use as food, they’ve been used medicinally and as dye among various cultures (they were also found preserved in the stomach contents of the 2500-year-old “Haraldskær Woman,” a bog body found in Denmark—indicating that these berries have been consumed for thousands of years!)

- Blueberries, which are small, sweet, and blue and grow both wild and domesticated

- Boysenberries, which are large and red, and are believed to be a hybrid between raspberries, blackberries, and loganberries first appearing in the 1920s

- Cloudberries, which also belong to the rose family and are amber-colored and tart

- Cranberries, which are tart and red and were used by indigenous tribes to make pemmican

- Goji berries or wolfberries, which are native to Asia and have been an ingredient in traditional Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese medicine since the 3rd century BC

- Gooseberries, which are another member of the Ribes genus and are round, brightly green colored, and striped

- Huckleberries, which are small and tart and can be red or blue

- Lingonberries, which are similar to cranberries but less tart

- Loganberries, which are purple hybrids of blackberries and raspberries

- Marionberries, which are cultivars of blackberries and have sweet, tart, complex flavors

- Mulberries, which grow on deciduous trees of the Morus genus and can be white, lavender, or black

- Raspberries, which are red (or for some cultivars, golden or purple) and whose name derives from raspise, meaning “a sweet-rose-colored wine”

- Red, white, and black currants, which are sweet members of the Ribes genus

- Salal berries, which are dark blue, distinctively flavored, and meaty textured

- Salmonberries, which belong to the rose family, resemble raspberries in shape and size, and have a subtle sweet taste

- Strawberries, which grow both wild and domesticated

- Tayberries, which are another hybrid of blackberries and raspberries but much larger

- Thimbleberries, which are delicate, sweet, and bright red

Fruit consumption in general is linked with health benefits, independent of vegetables, with scientific evidence pointing to 3 servings per day as a good minimum target (see Fruit is a Good Source of Carbs). Each family of fruit tends to have something unique to offer us nutrient-wise (see The Health Benefits of Apples and The Health Benefits of Citrus Fruits) and berries are no exception!

Berries Are Nutrient-Dense

Berries are well known for their nutrient density, and each variety has a unique profile of micronutrients and phytochemicals (see The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!). However, all berries tend to be high in vitamin C, fiber (cellulose, pectin, and hemicellulose, see The Many Types of Fiber), manganese, and in some cases vitamin K, while also being relatively low in calories and containing a range of other micronutrients. For example,

- Blueberries contain 84 calories per cup, 3.6 grams of dietary fiber, about a third of the DV for vitamin K, and a quarter of the DV for manganese and vitamin C.

- Strawberries contains 46 calories per cup and 150% of the DV for vitamin C;

- Raspberries contains 64 calories per cup and half the DV for manganese and vitamin C.

Berry seeds are also nutritious, contributing protein, fiber, carotenoids, ellagic acid, and ellagitannins—so don’t skip out on the seeds!

Certain polyphenols (especially anthocyanins and carotenoids) are what give berries their unique colors, and these fruits also contain phenolic acids, organic acids (such as citric acid, malic acid, oxalic acid, tartaric acid, and fumaric acid), flavonols, stilbenes, phytosterols (including sitosterol and stigmasterol), and tannins, which collectively contribute to their famous health benefits; see also Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?. And because berries are usually consumed fresh, their bioactive compounds generally remain intact and are not lost through cooking (see Is It Better to Eat Veggies Raw or Cooked?).

Health Benefits of Berries

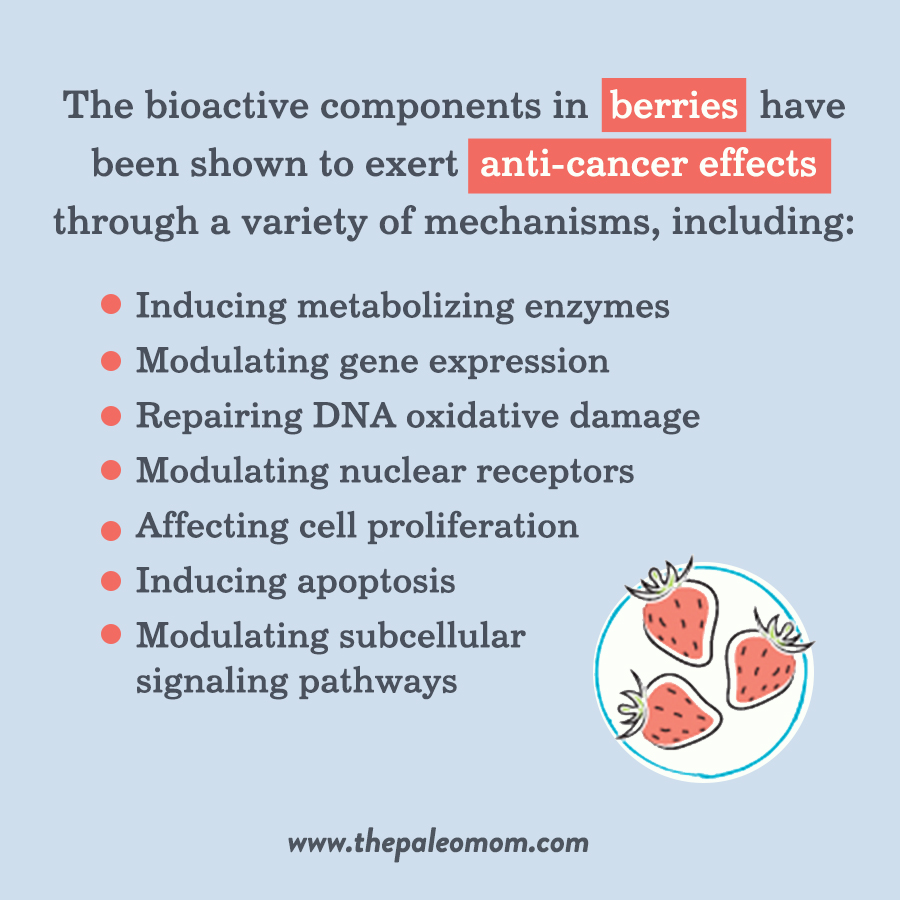

Indeed, abundant research has examined the effects of berries and their compounds on human health! The bioactive components in berries have been shown to exert anti-cancer effects through a variety of mechanisms, including inducing metabolizing enzymes, modulating gene expression, repairing DNA oxidative damage, modulating nuclear receptors, affecting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and modulating subcellular signaling pathways. Ellagic acid found in strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, and cranberries has been shown to exhibit antiviral and antioxidant activity, potentially protecting against lung cancer, colon cancer, and esophageal cancer. Gallic acid, also found in berries, inhibits cell proliferation in prostate cancer and has significant antioxidant activity (three times greater than vitamin E or C!). Extracts from several blackberry cultivars, black currants, red currants, black raspberries, and red raspberries have demonstrated high scavenging activity towards chemically generated superoxide radicals.

Indeed, abundant research has examined the effects of berries and their compounds on human health! The bioactive components in berries have been shown to exert anti-cancer effects through a variety of mechanisms, including inducing metabolizing enzymes, modulating gene expression, repairing DNA oxidative damage, modulating nuclear receptors, affecting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and modulating subcellular signaling pathways. Ellagic acid found in strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, and cranberries has been shown to exhibit antiviral and antioxidant activity, potentially protecting against lung cancer, colon cancer, and esophageal cancer. Gallic acid, also found in berries, inhibits cell proliferation in prostate cancer and has significant antioxidant activity (three times greater than vitamin E or C!). Extracts from several blackberry cultivars, black currants, red currants, black raspberries, and red raspberries have demonstrated high scavenging activity towards chemically generated superoxide radicals.

Quercetin in raspberries has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation in vitro (making it potentially useful in protecting against heart disease), and also possesses anti-cancer properties through inducing cell differentiation and inhibiting protein tyrosine kinase. Antioxidants in strawberries have been shown to reduce LDL cholesterol oxidation and improve endothelial function. The vitamin C found in strawberries, cranberries, blueberries, raspberries, and other berries likewise serves as an antioxidant and may help promote connective tissue development and immunity. Raspberry phytochemicals have been shown to modulate enzyme activity, gene expression, and cellular pathways, along with reducing the formation of oxidized LDL.

Berries also have potential anti-diabetic properties and neuroprotective properties. In rodents, behavioral studies have shown that strawberry, blueberry, or blackberry ingestion attenuates brain aging, and bilberry extracts fed to OXYS rats prevents learning and memory deficits. Antioxidants in blackberries have also been shown to improve behavior performance in motor neuron tests in aged rats.

Studies of berry consumption have confirmed that these benefits play out in real-world dietary settings, too—not just in vitro studies and animal models! For instance, in obese adults, daily consumption of blueberries (1.5 oz for eight weeks) reduced oxidized LDL cholesterol by 28% and also reduce blood pressure in adults. Another study showed that consuming 150 grams of a berry puree made of cranberries, strawberries, black currants, and bilberries led to a significantly lower peak glucose concentration compared to a control meal, confirming these fruits’ potential anti-diabetic effects. Another study found that consuming berries (strawberries, bilberries, lingonberries, or chokeberries) along with white bread significantly reduced the postprandial insulin response to the bread, while strawberries improved the glycemic profile of both white bread and rye bread. And, in a double-blind, randomized, controlled study of obese people with insulin resistance, drinking a blueberry smoothie twice daily for six weeks led to greater improvements in insulin sensitivity compared to a control smoothie. Another trial of overweight subjects found that adding a strawberry beverage to a high-carbohydrate, high-fat meal led to a more significant decrease in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and IL-6) than the control. And, a study of 44 people with metabolic syndrome found that consuming a daily blueberry smoothie led to significant improvements in endothelial function.

Studies of berry consumption have confirmed that these benefits play out in real-world dietary settings, too—not just in vitro studies and animal models! For instance, in obese adults, daily consumption of blueberries (1.5 oz for eight weeks) reduced oxidized LDL cholesterol by 28% and also reduce blood pressure in adults. Another study showed that consuming 150 grams of a berry puree made of cranberries, strawberries, black currants, and bilberries led to a significantly lower peak glucose concentration compared to a control meal, confirming these fruits’ potential anti-diabetic effects. Another study found that consuming berries (strawberries, bilberries, lingonberries, or chokeberries) along with white bread significantly reduced the postprandial insulin response to the bread, while strawberries improved the glycemic profile of both white bread and rye bread. And, in a double-blind, randomized, controlled study of obese people with insulin resistance, drinking a blueberry smoothie twice daily for six weeks led to greater improvements in insulin sensitivity compared to a control smoothie. Another trial of overweight subjects found that adding a strawberry beverage to a high-carbohydrate, high-fat meal led to a more significant decrease in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and IL-6) than the control. And, a study of 44 people with metabolic syndrome found that consuming a daily blueberry smoothie led to significant improvements in endothelial function.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Berries Improve Gut Health

Berries are also highly beneficial for our gut microbiota, both by encouraging the growth of beneficial commensals and probiotics and inhibiting the growth of potential pathogens; see What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?. For example, bioactive berry compounds selectively inhibit the potential pathogen Staphylococcus; Salmonella and Escherichia strains are also sensitive to some berry compounds, including ellagitannins. One study of Nordic berries showed that raspberries were the most potent pathogen inhibitors in general, while cranberries inhibited Listeria and Staphylococcus growth, and blueberries reduced endotoxin transport across the gut barrier. Berry compounds appear to exert their antibacterial effects through destabilizing the cytoplasmic membrane of pathogens, enhancing the permeability of the plasma membrane, inhibiting extracellular microbial enzymes, depriving bacteria of substrates required for growth, and directly acting on microbial metabolism.

Berries are also highly beneficial for our gut microbiota, both by encouraging the growth of beneficial commensals and probiotics and inhibiting the growth of potential pathogens; see What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?. For example, bioactive berry compounds selectively inhibit the potential pathogen Staphylococcus; Salmonella and Escherichia strains are also sensitive to some berry compounds, including ellagitannins. One study of Nordic berries showed that raspberries were the most potent pathogen inhibitors in general, while cranberries inhibited Listeria and Staphylococcus growth, and blueberries reduced endotoxin transport across the gut barrier. Berry compounds appear to exert their antibacterial effects through destabilizing the cytoplasmic membrane of pathogens, enhancing the permeability of the plasma membrane, inhibiting extracellular microbial enzymes, depriving bacteria of substrates required for growth, and directly acting on microbial metabolism.

In a study of constipated mice, mulberry increased fecal water content, shortened defecation time, increased the gastric-intestinal transit rate, and promoted gastric evacuation—suggesting notable benefits for constipation. At the same time, mulberry increased the fecal abundance of beneficial Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium while decreasing levels of Helicobacter and Prevotellaceae, and enhanced the production of SCFAs including acetic, propionic, butyric, isovaleric, and valeric acids.

Another study of mice found that four weeks of blueberry consumption (at intakes of 5% freeze-dried powder) decreased alpha-diversity, lowered the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, increased the abundance of Tenericutes, and decreased the abundance of Deferribacteres. Interestingly, male mice saw more pronounced changes in gut-microbe-associated fatty acid and lipid metabolism pathways, suggesting that the effects of blueberry consumption differ depending on biological sex. In rats, blueberry consumption (10% blueberry powder by weight) increased Gammaproteobacteria, improved markers of insulin sensitivity, and protected against high-fat-diet induced increases in tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1-beta expression in visceral fat. Additionally, blueberry extracts (from the cultivars Centurion and Maru) were shown to enhance the growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium when administered to rats daily for six days.

Another study of mice found that four weeks of blueberry consumption (at intakes of 5% freeze-dried powder) decreased alpha-diversity, lowered the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, increased the abundance of Tenericutes, and decreased the abundance of Deferribacteres. Interestingly, male mice saw more pronounced changes in gut-microbe-associated fatty acid and lipid metabolism pathways, suggesting that the effects of blueberry consumption differ depending on biological sex. In rats, blueberry consumption (10% blueberry powder by weight) increased Gammaproteobacteria, improved markers of insulin sensitivity, and protected against high-fat-diet induced increases in tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1-beta expression in visceral fat. Additionally, blueberry extracts (from the cultivars Centurion and Maru) were shown to enhance the growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium when administered to rats daily for six days.

Goji berries also impact the gut microbiota. In a study of IL-10-deficient mice supplemented with goji berries (1% of dry feed weight) for 10 weeks, the goji supplementation increased the abundance of Actinobacteria, including a significant increase in Bifidobacterium in the gut. Likewise, the goji berries promoted the growth of butyrate-producers from the Lachnospiraceae-Ruminococcaceae family, Roseburia species, Clostridium leptum, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.

Berries for the Win!

Whew! All that should be more than enough reason to make berries a regular part of our diet. The fact that they’re also delicious makes it easy! And as with all foods, variety is key, so choosing different berries among the ones available to us is wise!

Here’s a handy-dandy list of berries, for your convenience!

- açaí

- bearberry

- bilberry

- blackberry

- blueberry

- cloudberry

- cranberry

- crowberry

- currant

- elderberry

- falberry

- goji

- gooseberry

- grape

- hackberry

- huckleberry

- lingonberry

- loganberry

- mulberry

- muscadine

- nannyberry

- Oregon grape

- raspberry

- salmonberry

- sea buckthorn

- strawberry

- strawberry tree

- thimbleberry

- wineberry

Citations

Casto BC, et al. “Chemoprevention of oral cancer by lyophilized strawberries.” Anticancer Res. 2013 Nov;33(11):4757-66.

Edirisinghe I, et al. “Strawberry anthocyanin and its association with postprandial inflammation and insulin.” Br J Nutr. 2011 Sep;106(6):913-22. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511001176. Epub 2011 May 16.

Hu T-G, et al. “Protective effect of mulberry (Morus atropurpurea) fruit against diphenoxylate-induced constipation in mice through the modulation of gut microbiota.” Food Funct. 2019 Mar 20;10(3):1513-1528. doi: 10.1039/c9fo00132h.

Jenkins DJA, et al. “The effect of strawberries in a cholesterol-lowering dietary portfolio.” Metabolism. 2008 Dec;57(12):1636-44. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.018.

Kang Y, et al. “Goji Berry Modulates Gut Microbiota and Alleviates Colitis in IL-10-Deficient Mice.” Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018 Nov;62(22):e1800535. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800535. Epub 2018 Oct 7.

Lee S, et al. “Blueberry Supplementation Influences the Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Rats.” J Nutr. 2018 Feb 1;148(2):209-219. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx027.

Mentor-Marcel RA, et al. “Plasma cytokines as potential response indicators to dietary freeze-dried black raspberries in colorectal cancer patients.” Nutr Cancer. 2012 Aug;64(6):820-5. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.697597. Epub 2012 Jul 24.

Molan AL, et al. “In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the prebiotic activity of water-soluble blueberry extracts.” World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2009;25:1243-49.

Nile SH & Park SW. “Edible berries: bioactive components and their effect on human health.” Nutrition. 2014 Feb;30(2):134-44. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.04.007. Epub 2013 Sep 4.

Puupponen-Pimiä R, et al. “Berry phenolics selectively inhibit the growth of intestinal pathogens.” J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98(4):991-1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02547.x.

Skrovankova S, et al. “Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Different Types of Berries.” Int J Mol Sci. 2015 Oct 16;16(10):24673-706. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024673.

Stull AJ, et al. “Bioactives in Blueberries Improve Insulin Sensitivity in Obese, Insulin-Resistant Men and Women.” J Nutr. 2010 Oct; 140(10): 1764–1768.

Stull AJ, et al. “Blueberries improve endothelial function, but not blood pressure, in adults with metabolic syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.” Nutrients. 2015 May 27;7(6):4107-23. doi: 10.3390/nu7064107.

Subash S, et al. “Neuroprotective effects of berry fruits on neurodegenerative diseases.” Neural Regen Res. 2014 Aug 15;9(16):1557-66. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.139483.

Törrönen R, et al. “Berries modify the postprandial plasma glucose response to sucrose in healthy subjects.” Br J Nutr. 2010 Apr;103(8):1094-7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992868. Epub 2009 Nov 24.

Törrönen, et al. “Berries reduce postprandial insulin responses to wheat and rye breads in healthy women.” J Nutr. 2013 Apr;143(4):430-6.: 10.3945/jn.112.169771. Epub 2013 Jan 30.

Wankhade UD, et al. “Sex-Specific Changes in Gut Microbiome Composition following Blueberry Consumption in C57BL/6J Mice.” Nutrients. 2019 Feb 1;11(2):313. doi: 10.3390/nu11020313.