It is well-established that eating a diet abundant in fresh vegetables and fruits is good for our health. In fact, every serving of vegetables or fruit reduces risk of all-cause mortality (a measurement of overall health and longevity) by about 5%, with the greatest risk reduction seen when we consume eight or more servings per day (see The Importance of Vegetables). Eating plenty of veggies and fruits substantially reduces risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, obesity, and osteoporosis. But, what is less well-known is that each family of fruits and veggies confer unique health benefits (see for example, The Health Benefits of Cruciferous Vegetables, The Health Benefits of Citrus Fruits, The Health Benefits of Apples, The Health Benefits of Berries, Elevating Mushrooms to Food Group Status, and Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome). And, when it comes to nutritional bang for the calorie buck, it’s hard to beat leafy greens! Their reputation as a health food is well earned, and their versatility makes them easy to include in our diet.

It is well-established that eating a diet abundant in fresh vegetables and fruits is good for our health. In fact, every serving of vegetables or fruit reduces risk of all-cause mortality (a measurement of overall health and longevity) by about 5%, with the greatest risk reduction seen when we consume eight or more servings per day (see The Importance of Vegetables). Eating plenty of veggies and fruits substantially reduces risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, obesity, and osteoporosis. But, what is less well-known is that each family of fruits and veggies confer unique health benefits (see for example, The Health Benefits of Cruciferous Vegetables, The Health Benefits of Citrus Fruits, The Health Benefits of Apples, The Health Benefits of Berries, Elevating Mushrooms to Food Group Status, and Why Root Veggies Are Great for the Gut Microbiome). And, when it comes to nutritional bang for the calorie buck, it’s hard to beat leafy greens! Their reputation as a health food is well earned, and their versatility makes them easy to include in our diet.

Unlike most plant food groups, these veggies come from a variety of different taxonomic families and are defined as any plant leaves eaten as vegetables. They include over a thousand known edible members, such as:

- Arugula (or rocket), which is a peppery and bitter member of the Brassica family, originating from the coastal Mediterranean

- Beet greens, which are the above-ground leaves of beetroot and have a sweet, chard-like flavor

- Chard, which is actually a type of beet cultivated specifically to have flavorful, earthy, tender leaves and stems

- Collard greens, which belong to the Brassica family and have a mild, earthy, slightly bitter flavor

- Dandelion greens, which are the bitter, leafy portion of the dandelion plant (yep, the one we call a weed!)

- Escarole, which has dark, thick leaves with a sweet and slightly bitter flavor

- Endive, which is a member of the chicory family that grows in small heads and has a crisp, nutty flavor

- Frisée (sometimes known as curly endive), which is a member of the chicory family and has lacy, ruffled leaves

- Kale, which is a hearty, bitter member of the Brassica family that’s been cultivated since at least 2000 BC

- Lettuces (including romaine, red leaf, green leaf, oak, iceberg, butterhead, and summercrisp), which are members of the daisy family and were first cultivated in Ancient Egypt for the purpose of harvesting oil from their seeds

- Mustard greens, which are the leaves of the mustard plant and have frilled edges and a peppery, spicy taste

- Purslane, which is a succulent that often grows as a weed and has a slightly sour, salty taste

- Radicchio, which is a member of the chicory family with white and burgundy leaves and a bitter taste

- Rapini (also called broccoli rabe), which is a Brassica vegetable with a slightly bitter, nutty taste and small broccoli-like buds

- Sorrel, which is a narrow spade-like leafy green with a tart, acidic flavor

- Spinach, which is a delicately flavored green that has been cultivated for over 2000 years

- Turnip greens, which are the leaves that grow atop the turnip plant and have a slightly peppery taste

- Watercress, which is a spicy and slightly bitter aquatic green belonging to the Brassica family

And that’s just the tip of the leafy green iceberg! I’ve included a more complete list below.

Leafy Greens Are Nutrient-Dense

Leafy Greens Are Nutrient-Dense

Nutritionally, leafy greens have diverse micronutrient and phytonutrient profiles, but they all tend to be low in calories and high in fiber, folate, manganese, carotenoids, and vitamin K1 (which is involved in photosynthesis, and therefore is particularly high in plant leaves!).

For example,

- one cup of Swiss chard contains 374% of the DV for vitamin K and 44% of the DV for vitamin A (in the form of precursors);

- one cup of kale contains 684% of the DV for vitamin K and 206% of the DV for vitamin A;

- one cup of raw spinach contains 181% of the DV for vitamin K and 56% of the DV for vitamin A;

- one cup of chopped raw endive contains 144% of the DV for vitamin K; and

- one cup of shredded romaine lettuce contains 82% of the DV for vitamin A and 60% of the DV for vitamin K.

In addition, leafy greens are wonderful sources of phytonutrients, including lutein, nitrate, kaempferol, and quercetin.

Health Benefits of Leafy Greens

Across the board, leafy greens offer a huge range of scientifically demonstrated health benefits. In a prospective study of over 107,000 men and women, leafy green consumption was associated with a 40% lower risk of death from colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis of eight studies from around the globe found that intake of green leafy vegetables was associated with a 16% reduction in cardiovascular disease—possibly due to their bile acid binding capacity (helping reduce cholesterol levels), their nitrate content (helping contribute to the body’s nitrite and nitric oxide pools), specific micronutrients (such as magnesium), or certain phytonutrients (such as lutein, which acts as an antioxidant). A prospective study found that among older and elderly adults, the highest quintile of green leafy vegetable intake correlated with slower cognitive decline (an average of 1.3 servings per day was associated with the equivalent of being 11 years younger in cognitive age!).

Individual leafy greens and their components have also been studied. In vitro, watercress extract inhibits DNA damage and protects against additional stages of cancer progression. A case-control study found that eating lettuce more than three times per week reduced the risk of lung cancer by 49% (relative to eating almost no lettuce) among current and former smokers, and additional research from Japan and Hawaii showed that lettuce consumption is associated with a reduced risk of stomach cancer. When cooked, kale is a rich source of indole, a potent anti-cancer chemical. And one study even showed that ingesting 150 mL of kale juice daily for 12 weeks resulted in a significant drop in LDL, while also enhancing antioxidant systems!

Lactucaxanthin, a carotenoid found in lettuce, exhibits anti-diabetic activity when studied in vitro and in rats. The compounds lactucin and lactucopicrin in lettuce likewise have potent pain-reducing properties as well as a safe sleep-inducing effect. Red leaf lettuce, specifically, is high in anthocyanins that serve as antioxidants that can help fight inflammation and reduce several heart disease risk factors. Leafy green members of the Brassica family, including kale, watercress, arugula, turnip greens, beet greens, collard greens, and rapini, have another special feature: sulforaphane, a chemical with potent anti-cancer properties. The flavonoids quercetin and kaempferol present in leafy greens like kale have been extensively studied for their protective activity against heart disease, inflammation, cancer, and hypertension.

The high vitamin K content of leafy greens may likewise help protect against bone fracture, due to its role in maintaining skeletal health and bone mineral density. And, the folate in leafy greens like spinach is important for preventing neural tube defects, producing red blood cells, and having healthy pregnancies. Not to mention, the antioxidants lutein and beta-carotene (rich in most leafy greens) can help protect against conditions related to oxidative stress.

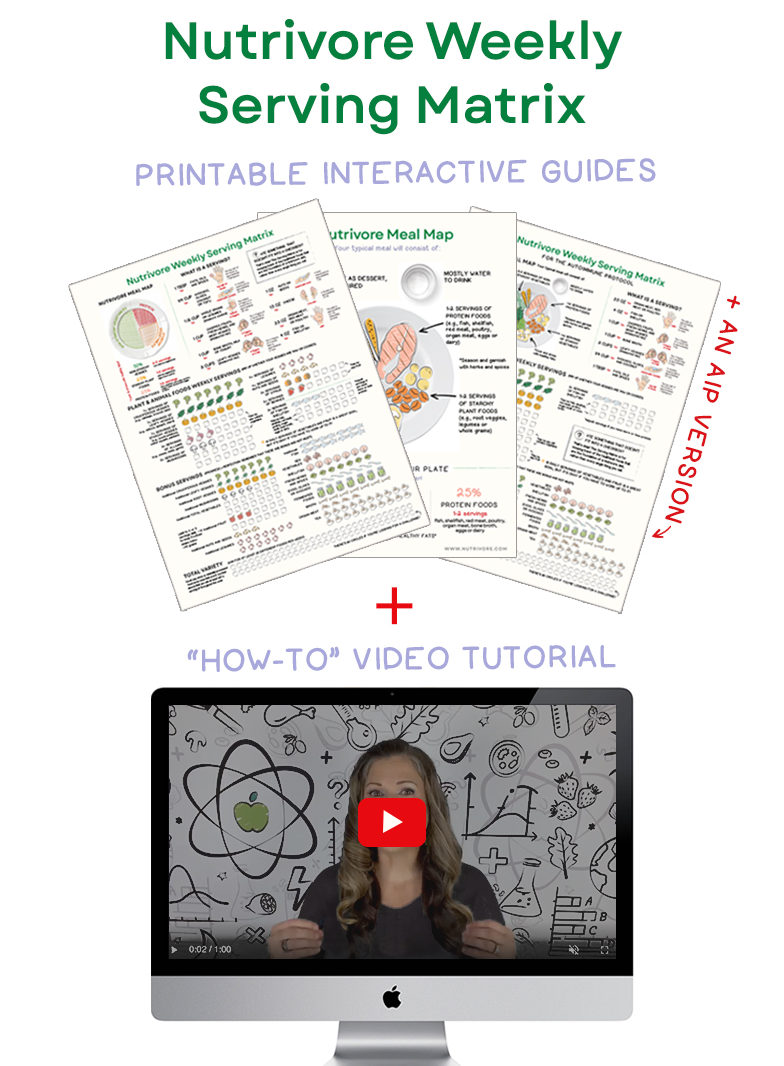

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Leafy Greens Improve Gut Health

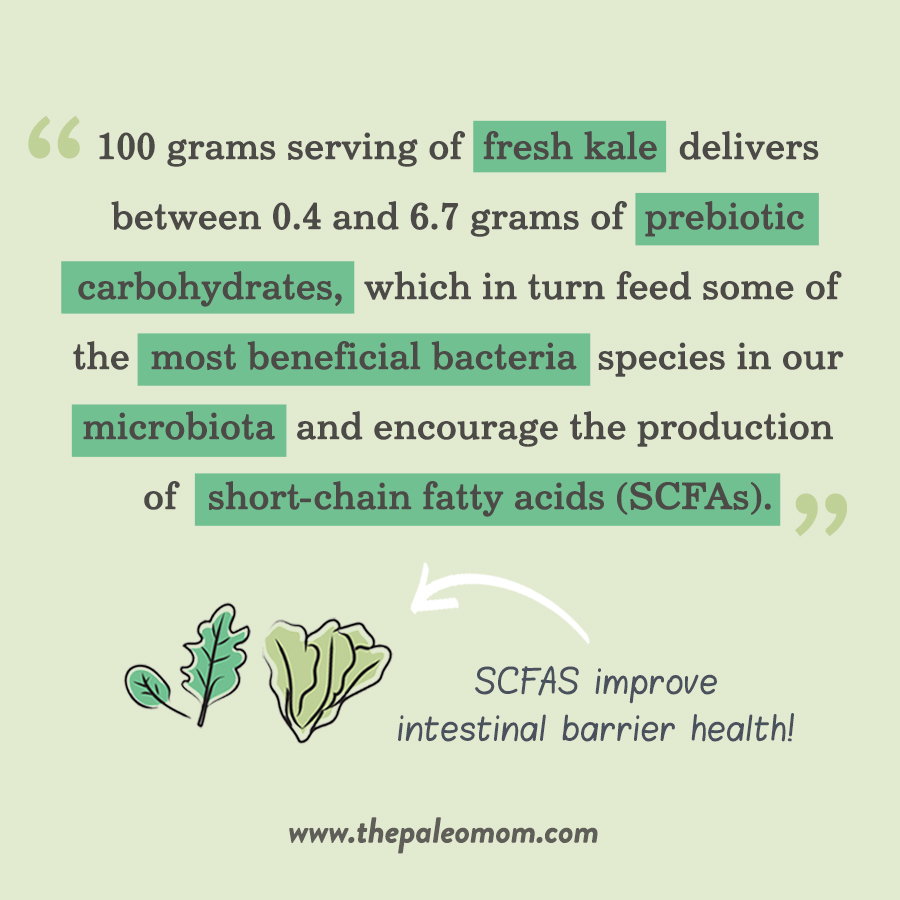

Leafy greens also happen to be a gut health superfood! One study found that a 100-grams serving of fresh kale delivers between 0.4 and 6.7 grams of prebiotic carbohydrates, which in turn feed some of the most beneficial bacteria species in our microbiota and encourage the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs (including acetate, butyrate and propionate) improve intestinal barrier health by providing intestinal and colonic epithelial cells with energy as well as driving cellular proliferation. They are also passively absorbed into the body, improving cellular health throughout the body. The liver can also use SCFAs as precursors for gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and cholesterologenesis. And, one of the best-studied and most important functions of SCFAs is their capacity to modulate the immune state and intestinal barrier function.

Leafy greens also happen to be a gut health superfood! One study found that a 100-grams serving of fresh kale delivers between 0.4 and 6.7 grams of prebiotic carbohydrates, which in turn feed some of the most beneficial bacteria species in our microbiota and encourage the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs (including acetate, butyrate and propionate) improve intestinal barrier health by providing intestinal and colonic epithelial cells with energy as well as driving cellular proliferation. They are also passively absorbed into the body, improving cellular health throughout the body. The liver can also use SCFAs as precursors for gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and cholesterologenesis. And, one of the best-studied and most important functions of SCFAs is their capacity to modulate the immune state and intestinal barrier function.

In mice, for example, the ingestion of commercial kale products for 12 weeks resulted in higher colonic butyrate levels. A study using mice with high-fat-diet induced obesity found that supplementation with red lettuce raised levels of butyrate-producing Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus, as well as Peptococcaceae (which oxidizes butyrate), while also tending to lower the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (a lower ratio is associated with leanness and lower inflammation)—effects owed to the polysaccharides in the lettuce.

The flavonoid quercetin in leafy greens has been shown to enhance microbial diversity and boost levels of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Clostridium while reducing levels of Fusobacterium and Enterococcus. And a unique sugar molecule in leafy greens, called sulfoquinovose, has also been shown to feed beneficial bacteria.

Hearty leafy greens like kale are also particularly rich in cellulose, boasting a higher content of this fiber than “softer” greens like lettuce (see also The Many Types of Fiber). Cellulose is usually only partially fermented in the gut due to its molecular structure, though species belonging to Clostridium, Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, and Bacteroides do have cellulose-degrading capacity. However, just because cellulose isn’t readily fermented doesn’t mean it can’t benefit the gut microbiota!

Hearty leafy greens like kale are also particularly rich in cellulose, boasting a higher content of this fiber than “softer” greens like lettuce (see also The Many Types of Fiber). Cellulose is usually only partially fermented in the gut due to its molecular structure, though species belonging to Clostridium, Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, and Bacteroides do have cellulose-degrading capacity. However, just because cellulose isn’t readily fermented doesn’t mean it can’t benefit the gut microbiota!

One study showed that when combined with resistant starch, cellulose was able to shift resistant starch fermentation throughout a greater portion of the gut, nearly doubling the amount of resistant starch being fermented between the proximal colon and feces, and significantly increasing the concentration of butyrate in the distal colon. (Without the cellulose, the resistant starch was rapidly fermented in the caecum and proximal colon, leaving little left for further down in the colon. All the more reason to eat some greens with our potatoes! See also Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses) A major benefit of this is the increased delivery of butyrate to regions of the colon where tumors commonly occur. Cellulose also appears to decrease colon transit time and increase the relative abundance of Bacteroidaceae. In piglets, pure cellulose was also shown to decrease levels of Eubacterium pyruvativorans and increase levels of Prevotella ruminicola.

Is It Better to Eat Leafy Greens Raw or Cooked?

So, what’s the best way to prepare leafy greens for maximum benefit? A mixture of raw and cooked does the trick!

On one hand, cooking greens results in the loss of some heat-sensitive nutrients like vitamin C, as well as partially destroys polyphenols and the enzyme myrosinase (which helps form sulforaphane from Brassica vegetables). But, cooking can also enhance nutrient bioavailability by beginning the breakdown of plant cell walls, increases antioxidants, and reduces levels of some anti-nutrients that normally block mineral absorption, such as oxalate.

For example, one study found that steam cooking reduced the oxalate content of Swiss chard leaves by 46% and of spinach by 42%, and boiling reduced the oxalate content of chard by 84% and of spinach by 87% (due largely to being lost in the cooking water). And, some research has shown that steaming collard greens, kale, and mustard greens enhances their bile acid binding capacity, suggesting that this form of cooking could boost the cholesterol-lowering effects of some greens. Some evidence also suggests that cooking can enhance the availability quercetin, lutein, and zeaxanthin in vegetables. (For more details, see Is It Better to Eat Veggies Raw or Cooked?)

How Much Leafy Greens?

Studies show that one or two servings per day of leafy greens is a great target, but there doesn’t seem to be any downside to consuming way more than that. For reference, a serving of leafy greens is equivalent to about 2 cups raw, or 1 cup cooked. And, as is the case with all vegetables and fruits, variety is super important, not just aiming to eat from as many as possible of the various vegetable and fruit families each day, but mixing it up within each family day to day. Lettuce today, kale tomorrow, spinach on Thursday!

Here’s a handy-dandy list of leafy greens, for your convenience!

- amaranth greens

- beet greens

- borage greens

- carrot tops

- cat’s ear

- celery

- celtuce

- Ceylon spinach

- chickweed

- chicory

- Chinese mallow

- chrysanthemum leaves

- cress

- dandelion

- endive

- fat hen

- fiddlehead

- fluted pumpkin leaves

- Good King Henry

- greater plantain

- komatsuna

- Lagos bologi

- lamb’s lettuce

- land cress

- lettuce

- melokhia

- New Zealand spinach

- orache

- pea leaves

- poke

- pumpkin sprouts

- radicchio

- radish sprouts

- sculpit (stridolo)

- sorrel

- spinach

- squash blossoms

- summer purslane

- sunflower sprouts

- sweet potato greens

- Swiss chard

- water spinach

- winter purslane

Citations

Boyd A, et al. “Assessment of the anti-genotoxic, anti-proliferative, and anti-metastatic potential of crude watercress extract in human colon cancer cells.” Nutr Cancer. 2006;55(2):232-41. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5502_15.

Chai W & Liebman M. “Effect of different cooking methods on vegetable oxalate content.” J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Apr 20;53(8):3027-30. doi: 10.1021/jf048128d.

Cheng DM, et al. “High phenolics Rutgers Scarlet Lettuce improves glucose metabolism in high fat diet-induced obese mice.” Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016 Nov;60(11):2367-2378. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600290. Epub 2016 Aug 16.

Elvira-Torales LI, et al. “Spinach consumption ameliorates the gut microbiota and dislipaemia in rats with diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).” Food Funct. 2019 Apr 17;10(4):2148-2160. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01630e.

Feskanish D, et al. “Vitamin K intake and hip fractures in women: a prospective study.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Jan;69(1):74-9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.74.

Gao CM, et al. “Protective effects of raw vegetables and fruit against lung cancer among smokers and ex-smokers: a case-control study in the Tokai area of Japan.” Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993 Jun;84(6):594-600. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb02018.x.

Gopal SS, et al. “Lactucaxanthin – a potential anti-diabetic carotenoid from lettuce (Lactuca sativa) inhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity in vitro and in diabetic rats.” Food Funct. 2017 Mar 22;8(3):1124-1131. doi: 10.1039/c6fo01655c.

Haenszel W, et al. “Stomach cancer in Japan.” J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976 Feb;56(2):265-74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.2.265.

Juskiewicz J, et al. “Effect of the dietary polyphenolic fraction of chicory root, peel, seed and leaf extracts on caecal fermentation and blood parameters in rats fed diets containing prebiotic fructans.” Br J Nutr. 2011 Mar;105(5):710-20. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004344. Epub 2010 Dec 7.

Kim HD, et al. “Sleep-inducing effect of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) varieties on pentobarbital-induced sleep.” Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017 May 29;26(3):807-814. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0107-1. eCollection 2017.

Kim SY. “Kale juice improves coronary artery disease risk factors in hypercholesterolemic men.” Biomed Environ Sci. 2008 Apr;21(2):91-7. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(08)60012-4.

Kojima M, et al. “Diet and colorectal cancer mortality: results from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study.” Nutr Cancer. 2004;50(1):23-32. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5001_4.

Larson AJ, et al. “Therapeutic potential of quercetin to decrease blood pressure: review of efficacy and mechanisms.” Adv Nutr. 2012 Jan;3(1):39-46. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001271. Epub 2012 Jan 5.

Li Y, et al. “Beneficial effects of a chlorophyll-rich spinach extract supplementation on prevention of obesity and modulation of gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed mice.” Journal of Functional Foods. 2019 Sep; 60.

Lin R, et al. “Dietary Quercetin Increases Colonic Microbial Diversity and Attenuates Colitis Severity in Citrobacter rodentium-Infected Mice.” Front Microbiol. 2019 May 16;10:1092. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01092. eCollection 2019.

Montelius C, et al. “Feeding spinach thylakoids to rats modulates the gut microbiota, decreases food intake and affects the insulin response.” J Nutr Sci. 2013 Jul 24;2:e20. doi: 10.1017/jns.2012.29. eCollection 2013.

Morris MC, et al. “Nutrients and bioactives in green leafy vegetables and cognitive decline.” Neurology. 2018 Jan 16;90(3):e214-e222. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004815. Epub 2017 Dec 20.

Pollock R. “The effect of green leafy and cruciferous vegetable intake on the incidence of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis.” JRSM Cardiovasc Dis. 2016 Aug 1;5:2048004016661435. doi: 10.1177/2048004016661435. eCollection Jan-Dec 2016.

Wesołowska A, et al. “Analgesic and sedative activities of lactucin and some lactucin-like guaianolides in mice.” J Ethnopharmacol. 2006 Sep 19;107(2):254-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.003. Epub 2006 Mar 17.