Winter squash is a generic term for members of the genus Cucurbita that grow through the summer and are harvested in the fall, when they’ve reached full maturation (unlike summer squash like zucchini, which are harvested when they’re immature). These vegetables have thick rinds, colorful skin, fully developed seeds, and dense, firm flesh, and can be stored for long periods without spoiling. They make great addition to soups, stews, casseroles, and other dishes that benefit from their hearty texture. And, they happen to be one of the oldest known crops: seeds dating back 12,000 years have been found in cave sites in Ecuador! (Along with being used for food, squashes were also used as containers, due to their hard shells.)

Winter squash is a generic term for members of the genus Cucurbita that grow through the summer and are harvested in the fall, when they’ve reached full maturation (unlike summer squash like zucchini, which are harvested when they’re immature). These vegetables have thick rinds, colorful skin, fully developed seeds, and dense, firm flesh, and can be stored for long periods without spoiling. They make great addition to soups, stews, casseroles, and other dishes that benefit from their hearty texture. And, they happen to be one of the oldest known crops: seeds dating back 12,000 years have been found in cave sites in Ecuador! (Along with being used for food, squashes were also used as containers, due to their hard shells.)

Winter squash include a number of colorful, tasty, uniquely shaped cultivars belonging to the species Cucurbita maxima, Curcubita moschata, Curcubita pepo. These include:

- Acorn squash, which is acorn-shaped and typically green, with firm flesh and a mild, nutty flavor.

- Buttercup squash, which is turban-shaped with dark green skin and sweet, creamy, golden flesh.

- Butternut squash, which is long and beige with bright orange flesh, and a dense, sweet, slightly nutty flavor.

- Carnival, festival, and heart of gold squash, which are hybrids of sweet dumpling and acorn squash. They have a sweet, nutty flavor along with a tender-firm texture.

- Delicata squash, which is oblong and yellow with green stripes, with a very sweet flavor similar to sweet potatoes.

- Hubbard squash, which is very large, blue or golden, and teardrop-shaped, with a buttery, pumpkin-like flavor.

- Kabocha squash, which is mottled blue and gray with smooth, dense, bright golden flesh and a sweet taste.

- Pie pumpkin (not to be confused with carving pumpkin!), which is orange and round with a mildly sweet flavor.

- Red Kuri, which is bright orange with a rich, sweet flavor and texture resembling chestnuts (in fact, “kuri” is the Japanese word for chestnut!).

- Spaghetti squash, which is cylindrical and yellow, with mildly flavored flesh that develops spaghetti-like strands after being cooked.

- Sweet dumpling squash, which is small and yellow with green striations, and has a sweet starchy flavor.

- Turban squash, which is turban-shaped and mottled orange, green, and yellow, with a very mild, nutty flavor.

Winter Squash Is Nutrient-Dense

Although each variety of winter squash has a unique nutritional profile, they all tend to be rich in beta-carotene, fiber, vitamin C, vitamin B6, magnesium, and potassium. (See also The Importance of Nutrient Density.)

Although each variety of winter squash has a unique nutritional profile, they all tend to be rich in beta-carotene, fiber, vitamin C, vitamin B6, magnesium, and potassium. (See also The Importance of Nutrient Density.)

For example, one cup of butternut squash contains 63 calories, 2.8 g of fiber, almost 300% of the DV for vitamin A in the form of carotenoids, 50% of the DV for vitamin C, and substantial potassium, manganese, magnesium, vitamin B6, vitamin E, and folate. One cup of spaghetti squash contains 46 calories, 32% of the DV for vitamin A, 21% of the DV for vitamin C, and substantial vitamin B6, potassium, and manganese. They’re also high in carotenoids (which give them their vibrant orange or yellow flesh!): along with alpha-carotene and beta-carotene, they contain flavoxanthin, luteoxanthin, auroxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, neoxanthin, neurosporene, phytofluene, taraxanthin, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin!

Fascinatingly, storing squash for extended periods of time doesn’t necessarily decrease its nutritional value in the way we see with many other vegetables. In fact, several studies have found that squash carotenoids (especially beta-carotene and lutein) increase with long-term storage (up to six months), possibly due to enzyme activity synthesizing new carotenoids or carotenoids in the outer parts of the squash migrating into the flesh.

Winter squash are also a rich source of certain phytonutrients (see also The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!). One study examining flesh from 15 different winter squash varieties identified numerous flavonols and phenolic acids, including quercetin, gallic acid, vanillic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, protocatechuic acid, and rutin. Different squash varieties also contain phytosterols, tannins, tocopherols, alkaloids, and curcurbitacin. Although the skin of many squash varieties is too tough or unpleasant to eat, varieties that do have edible skin (such as delicata, sweet dumpling, red kuri, acorn, and kabocha that’s been cooked a long time) offer added phytonutrients, since the skin is a concentrated source of many of these compounds.

Health Benefits of Winter Squash

Research has shown a number of health benefits associated with squash. In both diabetic humans and animal models, winter squash powder has a blood sugar-lowering effect, along with the ability to reduce triglycerides and total cholesterol. A study of 20 critically ill patients with diabetes found that administering 5 grams of lyophilized winter squash powder, once every 12 hours for three days, resulted in a significant decrease in blood sugar and lower insulin requirements. A trial using pumpkin juice was shown to reduce fasting blood sugar in diabetic patients. And in an observational study, among hyperglycemic Japanese men who smoked and drank alcohol, frequency of squash consumption (along with carrot consumption) was inversely associated with HbA1c, suggesting a role for managing blood sugar. Tetrasaccharide glyceroglycolipids derived from winter squash have been shown to significantly lower blood sugar levels in diabetic mice, and D-chiro-inositol extracted from Curcubita ficifolia (fig-leaf gourd) has hypoglycemic effects in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes.

Research has shown a number of health benefits associated with squash. In both diabetic humans and animal models, winter squash powder has a blood sugar-lowering effect, along with the ability to reduce triglycerides and total cholesterol. A study of 20 critically ill patients with diabetes found that administering 5 grams of lyophilized winter squash powder, once every 12 hours for three days, resulted in a significant decrease in blood sugar and lower insulin requirements. A trial using pumpkin juice was shown to reduce fasting blood sugar in diabetic patients. And in an observational study, among hyperglycemic Japanese men who smoked and drank alcohol, frequency of squash consumption (along with carrot consumption) was inversely associated with HbA1c, suggesting a role for managing blood sugar. Tetrasaccharide glyceroglycolipids derived from winter squash have been shown to significantly lower blood sugar levels in diabetic mice, and D-chiro-inositol extracted from Curcubita ficifolia (fig-leaf gourd) has hypoglycemic effects in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes.

Extracts from wild winter squash exhibit potent anti-cancer and COX-2-inhibitory activity, specifically due to their curcurbitacin content (biochemical compounds in the squash family that act as defenses against herbivores). Curcurbitacins B, D, E, and were shown to have anti-inflammatory and inhibitory activity against colon cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and central nervous system cancer cells. Additional research on curcubitacins shows that curcubitacin B, specifically, inhibits the growth of breast, cancer, cervix, liver, lung, uterine, skin, and brain cancer cells in vitro (more research is needed to study the effects of these substances in real-world humans!).

In addition, some of the nutrients abundant in squash are known to support human health. The carotenoids found in squash act as antioxidants and help reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and some cancers, and some are converted into vitamin A, which supports growth, reproductive health, and eye health. Likewise, the vitamin C in squash is another important antioxidant, and is needed for bone and joint health, since it serves as an enzyme cofactor for generating compounds like collagen, catecholamines, and carnitine.

Winter Squash Is Great for Gut Health

Through its fiber and carotenoid content, winter squash can significantly support the health of our gut microbiota (see also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?). In rats with type 2 diabetes, squash polysaccharide was shown to survive transit through the GI tract and serve as fermentable substrate for intestinal microbes, enhancing the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids. The squash polysaccharide also alleviated the rats’ diabetes via these metabolites! Likewise, pumpkin polysaccharide altered the gut microbiota of diabetic rats by enriching Bacteroidetes, Prevotella, Oscillospira, Sutterella, Bilophila, Phascolarctobacterium, and Veillonellaceae—while also enhancing SCFA production, improving insulin tolerance, reducing total and LDL cholesterol, decreasing blood sugar levels, and increasing HDL. Some carotenoids in squash, like astaxanthin, have also demonstrated antibacterial properties against pathogens like H. pylori; in mice, treatment with astaxanthin was able to reduce H. pylori bacterial loads and lower gastric inflammation. In other studies, this carotenoid has been shown to enhance levels of Proteobacteria and Bacteroides.

Through its fiber and carotenoid content, winter squash can significantly support the health of our gut microbiota (see also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?). In rats with type 2 diabetes, squash polysaccharide was shown to survive transit through the GI tract and serve as fermentable substrate for intestinal microbes, enhancing the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids. The squash polysaccharide also alleviated the rats’ diabetes via these metabolites! Likewise, pumpkin polysaccharide altered the gut microbiota of diabetic rats by enriching Bacteroidetes, Prevotella, Oscillospira, Sutterella, Bilophila, Phascolarctobacterium, and Veillonellaceae—while also enhancing SCFA production, improving insulin tolerance, reducing total and LDL cholesterol, decreasing blood sugar levels, and increasing HDL. Some carotenoids in squash, like astaxanthin, have also demonstrated antibacterial properties against pathogens like H. pylori; in mice, treatment with astaxanthin was able to reduce H. pylori bacterial loads and lower gastric inflammation. In other studies, this carotenoid has been shown to enhance levels of Proteobacteria and Bacteroides.

Many squash varieties are also high in acid-soluble pectin, a fiber that can be degraded by commensal bacteria in the gut and enhance SCFA production. Pectin has also been shown to reduce ammonia, delay gastric emptying, enhance the adhesion of Lactobacillus strains to gut epithelial cells, improve gut barrier integrity, enhance intestinal immunity, and improve mucosal proliferation. What’s more, pectins can simulate the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Bifiobacterium, Lactobacillus, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia, and Eubacterium rectale. More research is needed specifically on squash pectins to illustrate just how this fiber affects the human gut microbiota!

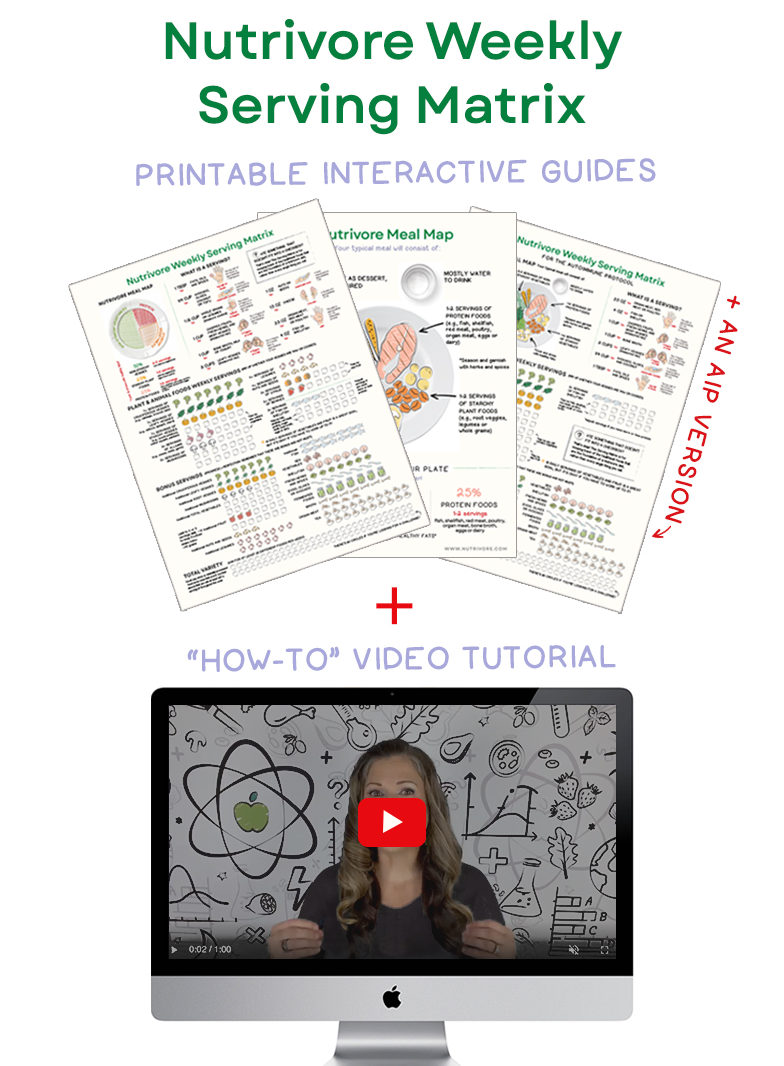

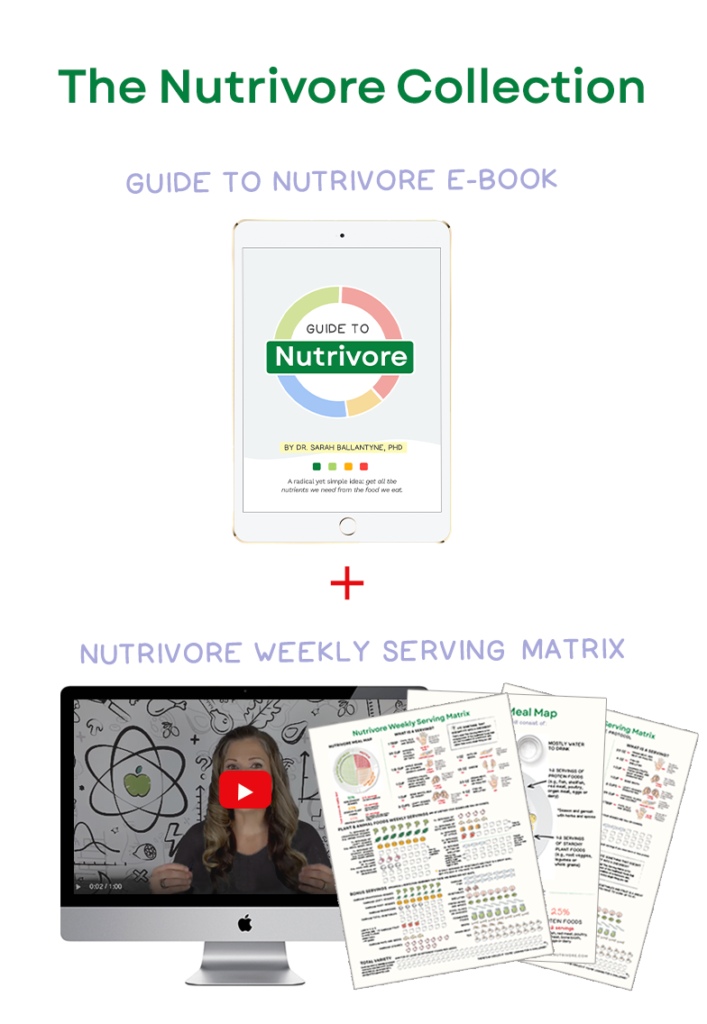

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Studies have also shown that avoidance of fruit and starchy vegetables like winter squash may cause unfavorable changes in the gut microbiome, such as a reduction in Roseburia and Bifidobacterium species, as discussed in Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding. See also The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body and How Many Carbs Should We Eat?.

Winter Squash for the Win!

Although winter squash hasn’t been as extensively studied in relation to human health as many other vegetables (see also The Importance of Vegetables, The Health Benefits of Cruciferous Vegetables, and The Health Benefits of Leafy Greens), the research we do have makes a good case for this food group earning a regular place at the table!

There’s a huge variety of winter squash to choose from beyond the varieties you’re likely to find at the store. They tend to be pretty easy to grow in your backyard from seed, and often you can start a squash plant from the (uncooked) seeds of a squash you purchased at the store or a local farmer’s market! Here’s a handy-dandy list of winter squash, for your convenience!

- Acorn squash

- Ambercup squash

- Arikara squash

- Atlantic Giant

- Autumn cup squash

- Autumn gold pumpkin

- Baby bear pumpkin

- Baby pam pumpkin

- Banana squash (aka Pink Banana squash)

- Bushkin pumpkin

- Buttercup squash

- Butternut squash

- Calabaza

- Carnival squash

- Cushaw (aka winter crookneck squash)

- Delicata squash (aka peanut squash)

- Fairytale pumpkin squash (aka Musquee de Provence)

- Gem squash

- Georgia candy roaster

- Giraumon

- Gold (or golden) nugget squash

- Harvest moon pumpkin

- Heart of gold squash

- Hubbard squash

- Jarrahdale pumpkin

- Kabocha

- Lakota squash

- Long Island cheese squash

- Lumina pumpkin

- Marina di Chioggia

- Mooregold squash

- Queensland blue pumpkin

- Red kuri squash (aka hokkaido squash or baby red Hubbard squash)

- Rouge vif d’Estampes

- Spaghetti squash

- Sugar loaf squash

- Sugar pumpkin

- Sweet dumpling squash

- Turban squash

- Winter Luxury pumpkin

Citations

Caili F, et al. “A review on pharmacological activities and utilization technologies of pumpkin.” Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2006 Jun;61(2):73-80. doi: 10.1007/s11130-006-0016-6.

Jaswir I, et al. “Effects of season and storage period on accumulation of individual carotenoids in pumpkin flesh (Cucurbita moschata).” J Oleo Sci. 2014;63(8):761-7. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess13186. Epub 2014 Jul 8.

Jiang Z & Du Q. “Glucose-lowering activity of novel tetrasaccharide glyceroglycolipids from the fruits of Cucurbita moschata.” Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011 Feb 1;21(3):1001-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.030. Epub 2010 Dec 10.

Kaur S, et al. “Functional and nutraceutical properties of pumpkin – a review.” Nutrition & Food Science. 2019 Aug 12;50(2):384-401. doi: 10.1108/NFS-05-2019-0143

Kulczyński B & Gramza-Michałowska A. “The Profile of Secondary Metabolites and Other Bioactive Compounds in Cucurbita pepo L. and Cucurbita moschata Pumpkin Cultivars.” Molecules. 2019 Aug 14;24(16):2945. doi: 10.3390/molecules24162945.

Larsen N, et al. “Potential of Pectins to Beneficially Modulate the Gut Microbiota Depends on Their Structural Properties.” Front Microbiol. 2019 Feb 15;10:223. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00223. eCollection 2019.

Liang L, et al. “Digestibility of squash polysaccharide under simulated salivary, gastric and intestinal conditions and its impact on short-chain fatty acid production in type-2 diabetic rats.” Carbohydr Polym. 2020 May 1;235:115904. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115904. Epub 2020 Jan 24.

Liu G, et al. “Pumpkin polysaccharide modifies the gut microbiota during alleviation of type 2 diabetes in rats.” Int J Biol Macromol. 2018 Aug;115:711-717. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.127. Epub 2018 Apr 24.

Lyu Y, et al. “Carotenoid supplementation and retinoic acid in immunoglobulin A regulation of the gut microbiota dysbiosis.” Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2018 Apr;243(7):613-620. doi: 10.1177/1535370218763760. Epub 2018 Mar 13.

Mahmoodpoor A, et al. “Effect of Cucurbita Maxima on Control of Blood Glucose in Diabetic Critically Ill Patients.” Adv Pharm Bull. 2018 Jun;8(2):347-351. doi: 10.15171/apb.2018.040. Epub 2018 Jun 19.

Suzuki K, et al. “[A study on serum carotenoid levels of people with hyperglycemia who were screened among residents living in a rural area of Hokkaido, Japan].” Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi . 2000 Jul;55(2):481-8. doi: 10.1265/jjh.55.481.

Xia T & Wang Q. “D-chiro-inositol found in Cucurbita ficifolia (Cucurbitaceae) fruit extracts plays the hypoglycaemic role in streptozocin-diabetic rats.” J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;58(11):1527-32. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.10.0014.