Nuts and seeds in moderation are a health-promoting food. A variety of studies have shown that a mere 20 grams of tree nuts per day is associated with substantially reduced risk (think 20-70%) of cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease, kidney disease, diabetes, infections, and mortality from respiratory disease. Nut consumption is also known to decrease markers of inflammation, and there’s emerging evidence of beneficial effects on oxidative stress, vascular reactivity, and hypertension. Even three 1-ounce servings per week can lower all-cause mortality risk by a whopping 39%, meaning that eating nuts on a regular basis both improves and extends lifespan (see Nuts and the Paleo Diet: Moderation is Key).

Nuts and seeds in moderation are a health-promoting food. A variety of studies have shown that a mere 20 grams of tree nuts per day is associated with substantially reduced risk (think 20-70%) of cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurodegenerative disease, kidney disease, diabetes, infections, and mortality from respiratory disease. Nut consumption is also known to decrease markers of inflammation, and there’s emerging evidence of beneficial effects on oxidative stress, vascular reactivity, and hypertension. Even three 1-ounce servings per week can lower all-cause mortality risk by a whopping 39%, meaning that eating nuts on a regular basis both improves and extends lifespan (see Nuts and the Paleo Diet: Moderation is Key).

However, people with autoimmune disease so commonly develop food intolerance to nuts and seeds that they are eliminated initially on the Autoimmune Protocol.

Nuts and Seeds Are Common Food Intolerances

Tree nuts are one of the most allergenic foods, with true allergies (meaning the body produces IgE antibodies against proteins in nuts) estimated at about 1% of the total population and some preliminary scientific studies showing that nut intolerance (meaning the body produces IgG antibodies against proteins in nuts) may affect a whopping 20 to 50% of us.

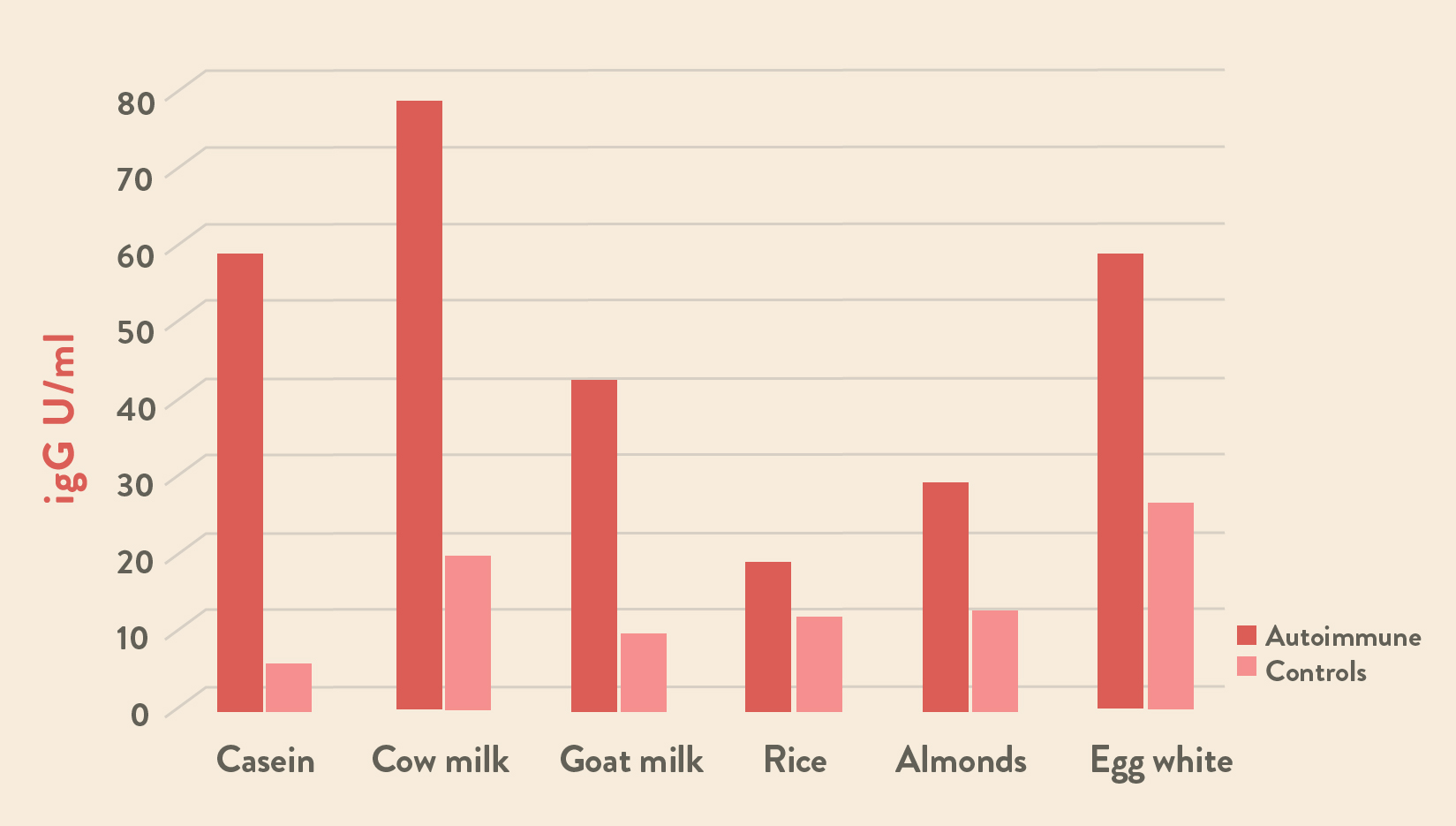

And, people with autoimmune disease are more likely to test positive on food intolerance panels than healthy people.

One 2018 study evaluated the level of IgG antibody production in autoimmune disease sufferers compared to healthy controls and found that autoimmune disease sufferers produce double and up to 10X more IgG antibodies against foods than healthy people.

The most common food intolerances in people with autoimmune disease are the foods already eliminated on the AIP because they are inflammatory, disrupt hormones, or negatively impact gut barrier health, including grains, dairy, egg whites and legumes (see How Gluten (and other Prolamins) Damage the Gut, Worse than Gluten: The Agglutinin Class of Lectins, 3 Myths About Legumes — Busted!, The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Eggs). The other foods that test positive with high frequency are nuts and seeds.

One 2015 study compared the frequency of IgG food intolerance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease sufferers compared to healthy controls. Nut and seed intolerance was very common, especially in Crohn’s disease sufferers.

| Nuts & Seeds | % Crohn’s patients with IgG Ab | % healthy controls with IgG Ab |

| Almond |

16 |

0 |

| Pecan |

38 |

0 |

| Sesame |

7 |

0 |

| Sunflower seed |

11 |

0 |

| Walnut |

7 |

0 |

In a 2004 study of people with unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms, something that is incredibly common among autoimmune disease sufferers, cashews are one of the most common nut intolerances, affecting upwards of 50% of study participants. In comparison, incidence of intolerance to almonds was about 28%, Brazil nuts was 23% and walnuts was 3%.

| Food | % IBS Patients with IgG Ab |

| Almond |

28 |

| Brazil nut |

22.7 |

| Cashew nut |

49.3 |

| Walnut |

2.7 |

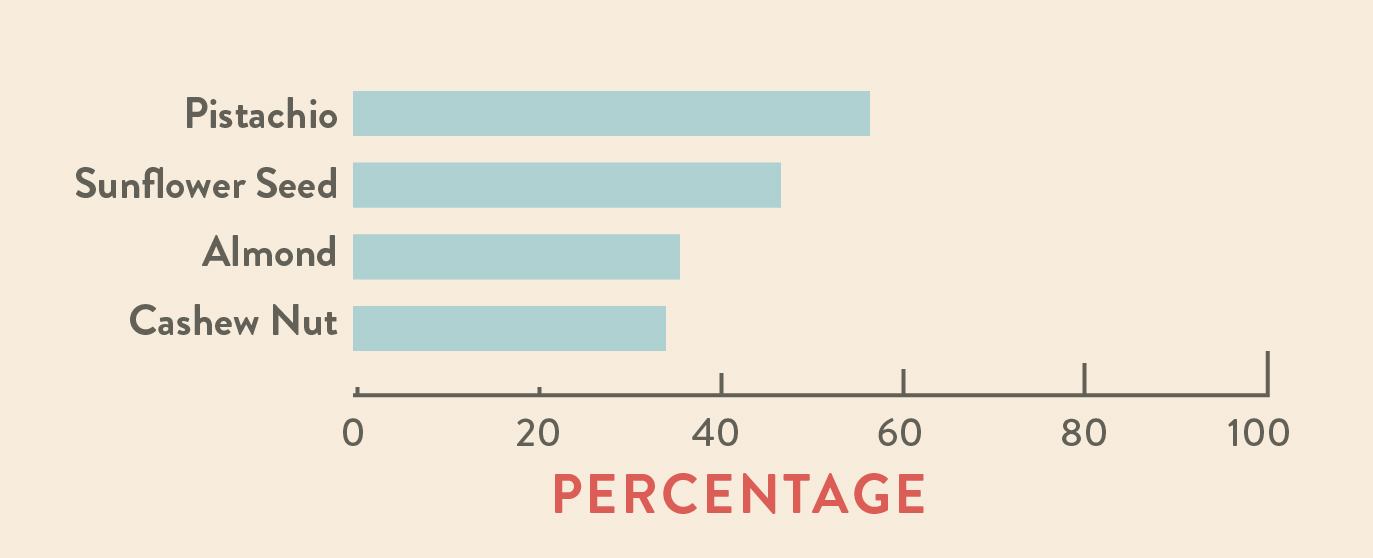

In a 2016 study of people with unexplained allergy symptoms, also common among autoimmune disease sufferers, pistachios were one of the most common nut intolerances, affecting upwards of 60% of study participants.

Save 70% Off the AIP Lecture Series!

Learn everything you need to know about the Autoimmune Protocol to regain your health!

I am loving this AIP course and all the information I am receiving. The amount of work you have put into this is amazing and greatly, GREATLY, appreciated. Thank you so much. Taking this course gives me the knowledge I need to understand why my body is doing what it is doing and reinforces my determination to continue along this dietary path to heal it. Invaluable!

Carmen Maier

Taken together, these studies make a strong case for eliminating nuts and seeds when first adopting the Autoimmune Protocol.

Testing for Allergy and Intolerance

For those nut and seed lovers out there who just can’t wrap their heads around elimination of these otherwise nutrient-dense and health-promoting foods, you may consider testing for food allergy and intolerance to nuts and seeds and decide which to eliminate based on the results. This can be done with a blood test that looks for IgE and IgG antibodies (and rarely, but sometimes IgA and IgM antibodies) against various food antigens. Panels can include anywhere between 50 and 500 different foods.

For those nut and seed lovers out there who just can’t wrap their heads around elimination of these otherwise nutrient-dense and health-promoting foods, you may consider testing for food allergy and intolerance to nuts and seeds and decide which to eliminate based on the results. This can be done with a blood test that looks for IgE and IgG antibodies (and rarely, but sometimes IgA and IgM antibodies) against various food antigens. Panels can include anywhere between 50 and 500 different foods.

You typically have to have eaten the food within the previous month in order for it to show up as a positive if you are intolerant (so you can’t necessarily believe a negative result if you haven’t eaten that food in a while). These tests can be an excellent way to expedite the process of determining which nuts and seeds need to be eliminated. There are even at-home versions like EverlyWell.

Keep in mind that an elimination and challenge is considered the gold standard for identifying food intolerances, and that allergists will typically follow up testing results with an elimination and challenge protocol. Also keep in mind that there are ways that we can negatively react to foods that we currently don’t have the capacity to test for, so a negative test result doesn’t automatically mean that food is a good choice for you.

Furthermore, IgG and IgE food allergy/intolerance panels do have a fairly high false positive (10%) and false negative (30%) rate. This is actually about the same as skin prick tests for allergies, which is why allergists will often follow up testing with an elimination diet and food antigen challenge. You can read more about the challenge protocol in The Reintroduction Quick-Start Guide: A New FREE download!).

Nuts and Seeds Are an Early Reintroduction

There are compelling reasons to prioritize reintroduction of nuts and seeds within the Reintroduction Phase of the Autoimmune Protocol, see The 3 Phases of the Autoimmune Protocol and Reintroducing Foods after Following the Autoimmune Protocol. Beyond their overall benefits (if you aren’t allergic or intolerant, that is!), nuts and seeds are a boon to the gut microbiome! See also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?.

There are compelling reasons to prioritize reintroduction of nuts and seeds within the Reintroduction Phase of the Autoimmune Protocol, see The 3 Phases of the Autoimmune Protocol and Reintroducing Foods after Following the Autoimmune Protocol. Beyond their overall benefits (if you aren’t allergic or intolerant, that is!), nuts and seeds are a boon to the gut microbiome! See also What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?.

Nuts (especially walnuts, pistachios, almonds and chestnuts) have been proven to benefit the gut microbiome thanks to their prebiotic fiber content. A number of well-designed studies have shown exceptional benefits from 1 to 2 ounces daily of walnuts, in particular, upon the health and composition of intestinal microbiota. Walnut enriched diets increase abundance of key probiotic strains of bacteria (including Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Ruminococcaceae, Faecalibacterium, Clostridium, Dialister, and Roseburia) while decreasing pathogenic strains. This microbiome shift is associated with reduced inflammation and lower LDL cholesterol. In fact, researchers concluded that the gut microbiota may play a direct role in some of the health benefits associated with walnuts! Almonds, pistachios and chestnuts have been similarly studied and, while walnuts reign supreme when it comes to microbiome health, these other nuts also all have proven benefits to microbiome composition and metabolite production. See also TWV Podcast Episode 413: The Gut Health Benefits of Nuts.

Reasons to Moderate Nuts and Seeds

Once you are have successfully reintroduced nuts and seeds, there are some compelling reason not to “go nuts” (hyuck, see what I did there?).

Nuts and seeds are also relatively concentrated sources of phytates. Phytate is the salt of phytic acid—that is, it is phytic acid bound to a mineral. Within the seed, the primary function of phytic acid is as a storage molecule for phosphorus, but it also serves as an energy store, as a source of cations (positive ions) for various chemical reactions in the plant, and as a source of a cell wall precursor called myoinositol. Because phytate is formed when phytic acid binds to minerals—typically calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, and zinc—these minerals are then unavailable to be absorbed by the gut. Therefore, the consumption of phytate-rich foods like grains and legumes can cause mineral deficiencies, especially when these phytate-rich foods displace other mineral-rich foods in the diet. Our gut bacteria can liberate some of these valuable minerals from phytates for us, but their capacity is limited, which might partially explain why we cease to see benefits from nut consumption beyond 20 grams daily.

Nuts and seeds are also relatively concentrated sources of phytates. Phytate is the salt of phytic acid—that is, it is phytic acid bound to a mineral. Within the seed, the primary function of phytic acid is as a storage molecule for phosphorus, but it also serves as an energy store, as a source of cations (positive ions) for various chemical reactions in the plant, and as a source of a cell wall precursor called myoinositol. Because phytate is formed when phytic acid binds to minerals—typically calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, and zinc—these minerals are then unavailable to be absorbed by the gut. Therefore, the consumption of phytate-rich foods like grains and legumes can cause mineral deficiencies, especially when these phytate-rich foods displace other mineral-rich foods in the diet. Our gut bacteria can liberate some of these valuable minerals from phytates for us, but their capacity is limited, which might partially explain why we cease to see benefits from nut consumption beyond 20 grams daily.

Along with blocking mineral absorption, phytates also limit the activity of a variety of digestive enzymes, including the proteases trypsin and pepsin, as well as amylase and glucosidase. This means that phytates can be as devastating to the gut barrier and gut microbiota as digestive enzyme inhibitors, namely by increasing gut permeability (by stimulating the pancreas to release excess digestive enzymes) and feeding bacterial overgrowth (by inhibiting digestion).

It’s important to emphasize that excessive dietary phytate and phytic acid are the problem. Phytates are also present in much lower concentrations in nonreproductive plant parts (like leaves and stems). Consuming phytates in more moderate quantities may actually provide an important antioxidant function and help reduce cardiovascular risk factors and cancer risk. Also, moderate consumption means that a healthy amount and variety of gut bacteria will be able to liberate some minerals from the phytate and make them more absorbable. In that sense, the scientific literature reinforces the idea that vegetables (with their lower concentration of phytates) are extremely important in our diet, whereas grains deliver levels of phytates that surpass what benefits us, and of course, nuts and seeds are great in moderation.

Furthermore, new research shows that, unlike legumes, soaking or “activating” nuts does not reduce the phytate content. In fact, for some nuts, soaking for 4 to 12 hours, with or without salt, actually increases phytates and reduces mineral content! This comes as quite a surprise because a variety of studies show that soaking, sprouting or fermenting dried bean type legumes can reduce phytate content by up to 85%, see Worse than Gluten: The Agglutinin Class of Lectins and The Green Bean Controversy and Pea-Gate.

Furthermore, new research shows that, unlike legumes, soaking or “activating” nuts does not reduce the phytate content. In fact, for some nuts, soaking for 4 to 12 hours, with or without salt, actually increases phytates and reduces mineral content! This comes as quite a surprise because a variety of studies show that soaking, sprouting or fermenting dried bean type legumes can reduce phytate content by up to 85%, see Worse than Gluten: The Agglutinin Class of Lectins and The Green Bean Controversy and Pea-Gate.

However, a 2020 study which compared different soaking methods and times in almonds, hazelnuts and walnuts showed that soaking caused anywhere from a 12% decrease to a 10% increase in phytates, along with small decreases or increases in calcium, iron and zinc concentrations that, when taken together, showed no benefit of soaking to the phytate to mineral ratio and no obvious pattern in whether a short or long soak was better or whether soaking with or without salt was better. For example, soaking almonds caused the phytate to increase from 531mg/100g to 562mg/100g (soaked for 12 hours with salt) or 578mg/100g (soaked for 12 hours without salt), while calcium concentration went down from 253mg/100g to 240mg/100g when soaked with salt but up to 264mg/100g when soaked without salt. Walnuts did see about a 5% decrease in phytates, from 523mg/100g to 501mg/100g (soaked for 12 hours with salt) but also saw the biggest decreases in calcium (88mg/100g down to 77mg/100g), iron (2.76mg/100g down to 2.52mg/100g) and zinc (2.93mg/100g down to 2.72mg/100g). A 2018 study showed that soaking almonds prior to consumption didn’t impact gastrointestinal tolerance in blinded participants. And finally, a 2020 study showed that soaking nuts did create an environment conducive to the growth of food-borne pathogens (especially above 15°C).

Overall, this new research shows small changes in phytates and minerals which show no benefit to soaking nuts before consuming; but also, if soaking is required for a recipe, it’s unlikely to be harmful (the changes in phytates in most studies are within 5% to 10%) provided that the soaking stage is performed under refrigeration to inhibit bacterial growth.

And finally, nuts and seeds also typically contain a large amount of polyunsaturated fats, usually the proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acids (see Why Grains Are Bad, Part 2, Omega 3 vs. 6 Fats and The Importance of Fish in Our Diets). Even the highest omega-3 content nuts (like walnuts) still have ratios of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in the neighborhood of 3 to 1, and many nuts and seeds only contain trace omega-3 fatty acids. Although their omega-6 content has often been used as rationale for limiting nut and seed consumption, most evidence suggests that when these foods are consumed in moderate amounts in whole form (opposed to highly processed oils stripped of most micronutrients and phytochemicals), their net effect is anti-inflammatory due to the presence of other beneficial compounds—such as vitamin E, dietary fiber, L-arginine, and phenolic compounds. In other words, omega-6 content alone doesn’t appear to be a reason to cut out nuts and seeds completely and instead reinforces the concept of moderate consumption.

And finally, nuts and seeds also typically contain a large amount of polyunsaturated fats, usually the proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acids (see Why Grains Are Bad, Part 2, Omega 3 vs. 6 Fats and The Importance of Fish in Our Diets). Even the highest omega-3 content nuts (like walnuts) still have ratios of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in the neighborhood of 3 to 1, and many nuts and seeds only contain trace omega-3 fatty acids. Although their omega-6 content has often been used as rationale for limiting nut and seed consumption, most evidence suggests that when these foods are consumed in moderate amounts in whole form (opposed to highly processed oils stripped of most micronutrients and phytochemicals), their net effect is anti-inflammatory due to the presence of other beneficial compounds—such as vitamin E, dietary fiber, L-arginine, and phenolic compounds. In other words, omega-6 content alone doesn’t appear to be a reason to cut out nuts and seeds completely and instead reinforces the concept of moderate consumption.

The Verdict on Nuts and Seeds

Overall, nuts and seeds are health-promoting, nutrient-dense foods that are best consumed in moderation (1 ounce per day, seepeople with allergies, sensitivities, and autoimmune disease, an elimination and challenge protocol is the best way to identify your own individual tolerance to specific nuts and seeds because intolerance to them is so common in these populations. Looking at the scientific evidence as a whole, the verdict on nuts and seeds is that they are best initially eliminated on the Autoimmune Protocol but are a compelling early reintroduction.

Citations

Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004 Oct;53(10):1459-64. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037697.

Coucke F. Food intolerance in patients with manifest autoimmunity. Observational study. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Nov;17(11):1078-1080. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.05.011.

Feng Y, Lieberman VM, Jung J, Harris LJ. Growth and Survival of Foodborne Pathogens during Soaking and Drying of Almond (Prunus dulcis) Kernels. J Food Prot. 2020 Dec 1;83(12):2122-2133. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-169.

Food Phytates; N.R. Reddy and S.K. Sathe, editors. 2002

Kawaguchi T, Mori M, Saito K, Suga Y, Hashimoto M, Sako M, Yoshimura N, Uo M, Danjo K, Ikenoue Y, Oomura K, Shinozaki J, Mitsui A, Kajiura T, Suzuki M, Takazoe M. Food antigen-induced immune responses in Crohn’s disease patients and experimental colitis mice. J Gastroenterol. 2015 Apr;50(4):394-405. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0981-8.

Kitts D, Yuan Y, Joneja J, Scott F, Szilagyi A, Amiot J, Zarkadas M. Adverse reactions to food constituents: allergy, intolerance, and autoimmunity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997 Apr;75(4):241-54.

Kumari S, Gray AR, Webster K, Bailey K, Reid M, Kelvin KAH, Tey SL, Chisholm A, Brown RC. Does ‘activating’ nuts affect nutrient bioavailability? Food Chem. 2020 Jul 30;319:126529. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126529.

Kunyanga CN, Imungi JK, Okoth MW, Biesalski HK, Vadivel V. Antioxidant and type 2 diabetes related functional properties of phytic acid extract from Kenyan local food ingredients: effects of traditional processing methods. Ecol Food Nutr. 2011 Sep-Oct;50(5):452-71. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2011.604588.

Lee LY, Mitchell AE. Determination of d-myo-inositol phosphates in ‘activated’ raw almonds using anion-exchange chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. J Sci Food Agric. 2019 Jan 15;99(1):117-123. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9151.

Shakoor Z, AlFaifi A, AlAmro B, AlTawil LN, AlOhaly RY. Prevalence of IgG-mediated food intolerance among patients with allergic symptoms. Ann Saudi Med. 2016 Nov-Dec;36(6):386-390. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.386.

Singh M and Krikorian AD. Inhibition of trypsin activity in vitro by phytate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982; 30(4):799–800. doi: 10.1021/jf00112a049

Taylor H, Webster K, Gray AR, Tey SL, Chisholm A, Bailey K, Kumari S, Brown RC. The effects of ‘activating’ almonds on consumer acceptance and gastrointestinal tolerance. Eur J Nutr. 2018 Dec;57(8):2771-2783. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1543-7.

Vaintraub IA and Bulmaga VP. Effect of phytate on the in vitro activity of digestive proteinases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991; 39 (5): 859–861. doi: 10.1021/jf00005a008