Eating 8+ servings of fresh vegetables and fruits daily lowers risk of chronic disease more than any other dietary factor (see The Importance of Vegetables), but is it better to eat those veggies raw or cooked? There are many people out there who will tell you that cooking vegetables destroys the nutrients and beneficial enzymes within. This is partially true. It is also true that cooking vegetables makes many of the nutrients within more easily absorbed and used by your body. So, which is better: Eating vegetables raw or cooked?

Cooking Foods Increases Digestible Energy

Heat alters chemical structures, typically unraveling the three-dimensional structures of complex molecules (for example, denaturing of protein as in the image below) and even breaking large molecules into smaller ones. So, intuitively, it makes sense that these straighter, shorter molecules would be easier to further break apart by our digestive enzymes, meaning that cooking food makes it easier to digest. And, studies bare this out.

Studies confirm that cooking food increases how much energy we get from food. A landmark 2011 study out of Harvard fed two groups of mice a series of diets that consisted of either meat or sweet potatoes prepared in four ways — raw and whole, raw and pounded, cooked and whole, and cooked and pounded. Over 40 days, the researchers tracked changes in the body mass of the mice, controlling for how much they ate and ran on an exercise wheel. The study found that cooked foods (both meat and sweet potatoes) delivered more energy to the mice than raw and that the improvement in energy digestibility from cooking was more than that from the pounded foods.

Interestingly, hungry mice also demonstrated a strong preference for cooked foods. While we modern humans aren’t very good at eating instinctively (thanks to hyper-palatable addictive modern foods, see Paleo for Weight Loss), most animals have a strong instinct for the most energy-dense and nutrient-dense foods.

A follow-up study from the same laboratory evaluated the effect of cooking on how much energy mice actually digest from fat-rich foods and found the same thing: cooking increased the digestible energy (although in this case, blending the fat had no detectable benefits).

One of the implications of this research is that a calorie is not necessarily a calorie. Calories on a food label don’t actually reflect digestibility. The original method used to determine the number of calories (okay, technically kcals) in a given food used what was called a bomb calorimeter to directly measured the energy it produced when that food was burned. The food in question would be placed in a sealed container surrounded by water then completely burned and the resulting rise in water temperature was measured, yielding the number of calories in the food. Nowadays, calories are calculated based on food components, a system called the Atwater system, which allots 4 calories for every gram of protein or carbohydrates (fiber is subtracted from total carbohydrate grams first), 9 calories per gram of fat, and 7 calories per gram of alcohol. But how much potential energy the food has is different than how much energy we get from eating it. In fact, the authors of these fascinating studies conclude that their results “also illuminate a weakness in current food labeling practices, which systematically overestimate the caloric potential of poorly processed foods.”

The fact that cooking food increases the energy we can digest from it was likely a key driver of human evolution. Prehistoric man mastered the art of fire and cooking perhaps as early as 1.5 million years ago, with good evidence that humans were controlling fire and cooking regularly by 800,000 years ago. This means that for the majority of human evolution, our ancestors have been eating cooked food. In fact, some researchers believe that the advent of cooking may be one of the most important factors in our success as a species because it greatly increased the energy that could be digested out of our food for a lower energy expenditure, meaning more calories for less work (this is true for meat and plant matter). Because early hominids could spend less time hunting, gathering, eating and digesting in order to get adequate energy, they could spend more time doing cognitively like communicating and socializing, leading early hominids to develop bigger and bigger brains. In fact, our huge Homo sapiens brains use 20-25% of the calories we burn every day.

As an aside, an earlier key driver of human evolution was the intake of starchy roots and tubers and persistent carnivory approximately 1.9 million years ago, which also increased the energy density of early hominid diets (see The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 1: Evolution & Hunter-Gatherers.) If you plot how brain size as increased over the last 3 million years of evolution, you see a steady, accelerating pattern of brain growth. Many researchers believe this rapid brain growth (yes, quadrupling the size of our brains over 3,000,000 yeas is considered rapid) was supported by shifts in diet (including learning to eat new foods with higher energy density and learning new preparation techniques like pounding foods into mashes and cooking) that eliminated energy constraints on brain development via natural selection.

Effects of Cooking on Micronutrients

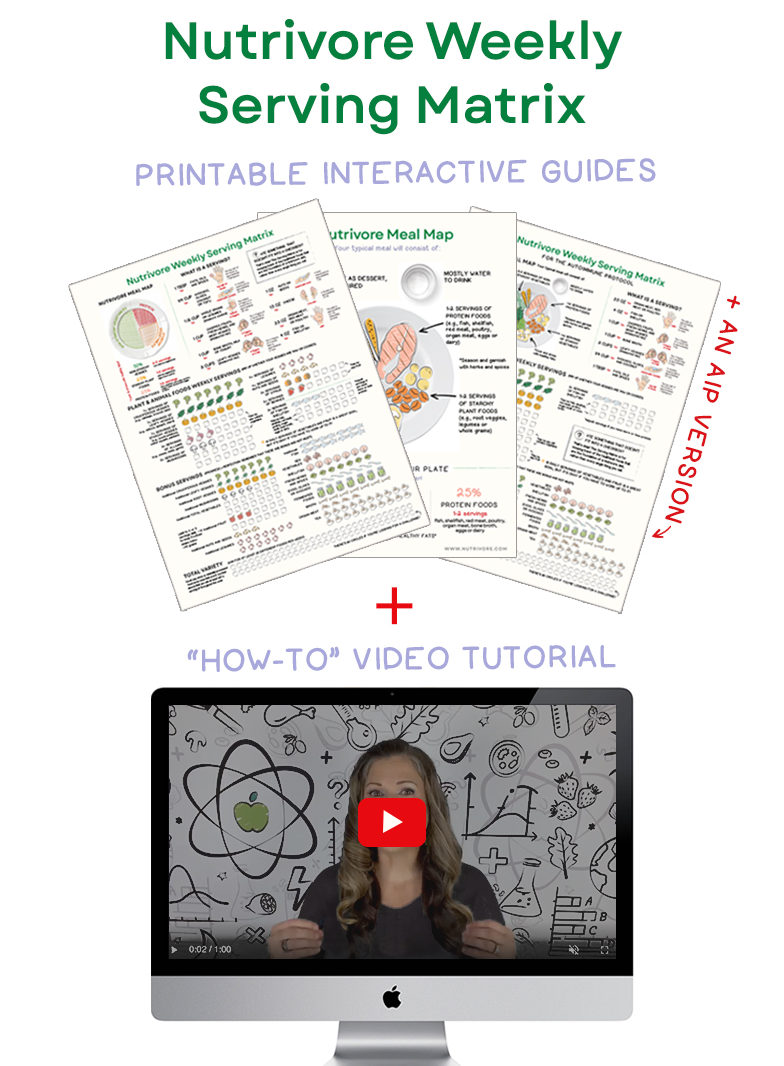

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

So, our bodies can extract more energy from cooked foods compared to raw when we eat them, but does that also mean we can glean more nutrition from those foods? There’s two sides to this coin: how cooking food affects its inherent nutritional properties (i.e., does heat degrade nutrients or form them?) and how cooking food affects absorbability of those nutrients.

Some micronutrients are very volatile in heat. Vitamin C for example, degrades with heat, dehydration and prolonged storage (see Vitamin C. Polyphenols are antioxidants known to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer which are partially destroyed by the cooking process (see Polyphenols: Magic Bullet or Health Hype?). There are some beneficial enzymes that are destroyed by the cooking process; for example: the enzyme myrosinase, whose activity forms sulforaphane, known to prevent cancer, is found in raw broccoli but destroyed in cooking (see The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!). (Studies confirm that sulforaphane is absorbed much more rapidly after consuming raw compared to cooked broccoli.) The allicin in garlic (the compound in garlic responsible for its antibiotic and anti-microbial effects, also shown to reduce the risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease) is destroyed by heat. There is some very convincing evidence supporting the case for eating raw vegetables.

While some nutrients are lost in cooking, we are compensated by the many other nutrients that are increased during cooking. Heat breaks down the thick walls of a plant’s cells, which makes any nutrients bound to the cell wall or locked inside the cells available to our body for digestion. Plus, heat can deactivate many anti-nutrients which would otherwise block absorption (including phytic acid, trypsin inhibitor, hemagglutinin and tannin). Typically, anti-oxidants are dramatically increased by cooking. For example, many the levels of carotenoids increase when vegetables that contain them are cooked. Lycopene increases when tomatoes are cooked or sun-dried. And some compounds require heat to be formed, such as indole, thought to prevent cancer, which is formed when cruciferous vegetables (like broccoli, cabbage, Brussels sprouts and kale) are cooked. A study done in bambaragroundnut seeds showed that cooking increased the amount of calcium, magnesium and iron while decreasing the amount of phosphorous, potassium and copper. The bioavailability of calcium, iron and zinc is dramatically higher in cooked white beans compared to raw,

There’s a handful of studies showing that cooking method can make a difference in terms of micronutrient absorption. One study compared the iron content of raw versus cooked bananas. While cooked bananas contained higher iron (another check in the cooking can increase nutrients box), the absorption was significantly higher in raw bananas (it was about a zero sum game in the end). Another study looked at the absorption of magnesium and calcium from spinach that was either raw, boiled or fried. Absorption of magnesium was highest in raw and fried spinach (and lower in boiled spinach) and the absorption of calcium was highest in raw spinach with a modest decline in boiled spinach but was way lower in fried spinach. Not only does cooking increase amount of carotenoids in many vegetables, they it also increases the bioavailability of those carotenoids, meaning they are more readily absorbed into the body. In fact, studies show much higher levels of carotenoids in the blood of volunteers after eating boiled carrots compared to raw carrots.

There’s a handful of studies showing that cooking method can make a difference in terms of micronutrient absorption. One study compared the iron content of raw versus cooked bananas. While cooked bananas contained higher iron (another check in the cooking can increase nutrients box), the absorption was significantly higher in raw bananas (it was about a zero sum game in the end). Another study looked at the absorption of magnesium and calcium from spinach that was either raw, boiled or fried. Absorption of magnesium was highest in raw and fried spinach (and lower in boiled spinach) and the absorption of calcium was highest in raw spinach with a modest decline in boiled spinach but was way lower in fried spinach. Not only does cooking increase amount of carotenoids in many vegetables, they it also increases the bioavailability of those carotenoids, meaning they are more readily absorbed into the body. In fact, studies show much higher levels of carotenoids in the blood of volunteers after eating boiled carrots compared to raw carrots.

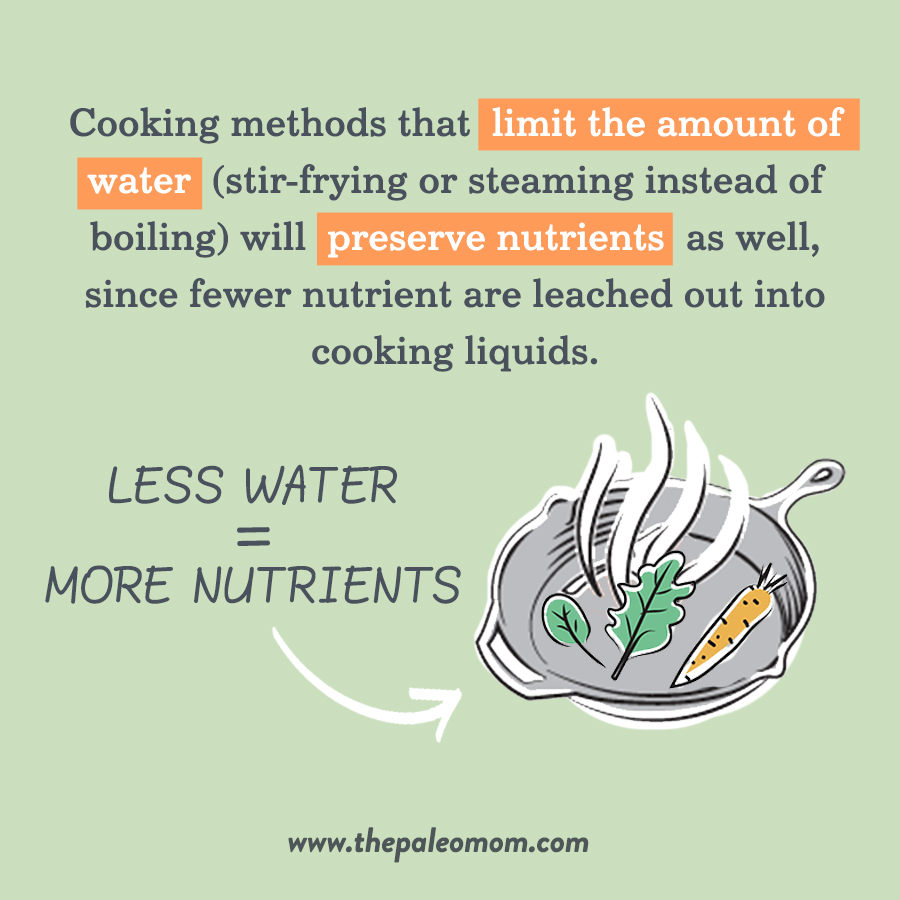

All in all, there’s a trade-off in terms of micronutrients when it comes to eating vegetables raw or cooked. In general, cooking methods that limit the amount of water (stir-frying or steaming instead of boiling) will preserve nutrients as well, since fewer nutrient are leached out into cooking liquids.

Is Cooked Fiber Better or Worse for the Microbiome?

Eating a high-fiber diet is the most important thing you can do to support a healthy and diverse gut microbiome (see The Fiber Manifesto Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good? , The Fiber Manifesto Part 2 of 5: The Many Types of Fiber and The Fiber Manifesto Part 3 of 5: Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber), but this conversation on the pros and cons of cooked versus raw veggies begs the question: does it matter to our gut bacteria if the fiber we’re eating is raw or cooked?

Eating a high-fiber diet is the most important thing you can do to support a healthy and diverse gut microbiome (see The Fiber Manifesto Part 1 of 5: What Is Fiber and Why Is it Good? , The Fiber Manifesto Part 2 of 5: The Many Types of Fiber and The Fiber Manifesto Part 3 of 5: Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber), but this conversation on the pros and cons of cooked versus raw veggies begs the question: does it matter to our gut bacteria if the fiber we’re eating is raw or cooked?

Only a handful of studies have actually looked at this, and their results are really interesting. One study showed that cooked carrots resulted in faster fermentation by porcine gut bacteria and higher levels of short-chain fatty acids in feces compared to raw carrots. Another study looking at wheat fiber that was either raw, lightly toasted or fully toasted showed that Bifidobacterium didn’t much care whether the fiber was raw or cooked but Lactobacillus sure did: only the raw fiber supported the growth of Lactobacillus strains. (See What Is the Gut Microbiome? And Why Should We Care About It?, The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods and The Benefits of Probiotics).

The most thorough paper to look at differential effects on the gut microbiome of raw versus cooked fiber evaluated the changes in relative abundance of bacterial species (genera, families and phyla) after consumption of raw versus heat-treated brown seaweed fiber. Raw fiber dramatically increased growth of bacteria from the Bacteroidetes phylum, but heat-treated fiber increased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (a higher Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio is associated with high-vegetable consumption). Fiber in general was associated with more bacterial species that are associated with leanness and fewer species associated with obesity, but cooked fiber had even fewer obesity-related bacteria species in the gut microbiome. The microbiome of the mice fed the raw brown seaweed fiber had the lowest level of possibly pathogenic bacteria. Raw fiber increased Lactobacillus growth whereas consumption of heat-treated fiber reduced Lactobacillus while supporting growth of Clostridium and Bacteroides. Overall, raw fiber supports more lactic acid-producing bacteria whereas heat-treated fiber supports more butyric acid-producing bacteria. Fascinating stuff, right?

Again, this data seems to support that, from a microbiome standpoint, it’s likely best to mix it up when it comes to eating veggies raw or cooked. And, it’s probably important to eat some raw veggies and some cooked veggies on a daily basis (since changing up fiber intake can shift the microbiome dramatically in as little as 2 or 3 days).

To Cook or Not To Cook (that is the question)

As you can see, there’s benefits to both raw and cooked vegetables, so I advise mixing it up. Cook some of your vegetables and eat some others raw. Sometimes cook your carrots; sometimes eat them straight out of the bag. Out of sheer convenience, I typically eat raw vegetables at breakfast and lunch and cooked vegetables at supper. Do whatever works for you. Eat your vegetables however they taste the best to you (see The Importance of Vegetables). The most important thing is that you eat them!

Citations

Carmody RN, Weintraub GS, Wrangham RW. Energetic consequences of thermal and nonthermal food processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Nov 29;108(48):19199-203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112128108. Epub 2011 Nov 7.

Carmody RN, Wrangham RW. The energetic significance of cooking. J Hum Evol. 2009 Oct;57(4):379-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.02.011. Epub 2009 Sep 3.

Comparison of content and in vitro bioaccessibility of provitamin A carotenoids in home cooked and commercially processed orange fleshed sweet potato (Ipomea batatas Lam). Berni P, Chitchumroonchokchai C, Canniatti-Brazaca SG, De Moura FF, Failla ML. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2015 Mar;70(1):1-8. doi: 10.1007/s11130-014-0458-1.

Connolly ML, Lovegrove JA, Tuohy KM. In vitro fermentation characteristics of whole grain wheat flakes and the effect of toasting on prebiotic potential. J Med Food. 2012 Jan;15(1):33-43. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0006. Epub 2011 Aug 30.

Day L, Gomez J, Øiseth SK, Gidley MJ, Williams BA. Faster fermentation of cooked carrot cell clusters compared to cell wall fragments in vitro by porcine feces. J Agric Food Chem. 2012 Mar 28;60(12):3282-90. doi: 10.1021/jf204974s. Epub 2012 Mar 19.

Dewanto V, Wu X, Adom KK, Liu RH. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2002 May 8;50(10):3010-4.

Gahler S, Otto K, Böhm V. Alterations of vitamin C, total phenolics, and antioxidant capacity as affected by processing tomatoes to different products. J Agric Food Chem. 2003 Dec 31;51(27):7962-8.

García OP, Martínez M, et al. Iron absorption in raw and cooked bananas: a field study using stable isotopes in women. Food Nutr Res. 2015 Feb 5;59:25976. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v59.25976. eCollection 2015.

Ghavami A, Coward WA, Bluck LJ. The effect of food preparation on the bioavailability of carotenoids from carrots using intrinsic labelling. Br J Nutr. 2012 May;107(9):1350-66. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100451X. Epub 2011 Sep 19.

Groopman EE, Carmody RN, Wrangham RW. Cooking increases net energy gain from a lipid-rich food. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2015 Jan;156(1):11-8. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22622. Epub 2014 Oct 8.

Imsic M, Winkler S, Tomkins B, Jones R. Effect of storage and cooking on beta-carotene isomers in carrots ( Daucus carota L. cv. ‘Stefano’). J Agric Food Chem. 2010 Apr 28;58(8):5109-13. doi: 10.1021/jf904279j.

Jeffery JL, Turner ND, King SR. Carotenoid bioaccessibility from nine raw carotenoid-storing fruits and vegetables using an in vitro model. J Sci Food Agric. 2012 Oct;92(13):2603-10. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5768. Epub 2012 Jul 17.

Kikunaga S, Ishii H, Takahashi M. The bioavailability of magnesium in spinach and the effect of oxalic acid on magnesium utilization examined in diets of magnesium-deficient rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1995 Dec;41(6):671-85.

Kim JY, Kwon YM, et al. Effects of the Brown Seaweed Laminaria japonica Supplementation on Serum Concentrations of IgG, Triglycerides, and Cholesterol, and Intestinal Microbiota Composition in Rats. Front Nutr. 2018 Apr 12;5:23. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00023. eCollection 2018.

Lemmens L, Van Buggenhout S, Van Loey AM, Hendrickx ME. Particle size reduction leading to cell wall rupture is more important for the β-carotene bioaccessibility of raw compared to thermally processed carrots. J Agric Food Chem. 2010 Dec 22;58(24):12769-76. doi: 10.1021/jf102554h. Epub 2010 Dec 1.

Livny O, Reifen R, Levy I, Madar Z, Faulks R, Southon S, Schwartz B. Beta-carotene bioavailability from differently processed carrot meals in human ileostomy volunteers. Eur J Nutr. 2003 Dec;42(6):338-45.

Moelants KR, Lemmens L, Vandebroeck M, Van Buggenhout S, Van Loey AM, Hendrickx ME. Relation between particle size and carotenoid bioaccessibility in carrot- and tomato-derived suspensions. J Agric Food Chem. 2012 Dec 5;60(48):11995-2003. doi: 10.1021/jf303502h. Epub 2012 Nov 27.

Nugrahedi PY, Verkerk R, Widianarko B, Dekker M. A mechanistic perspective on process-induced changes in glucosinolate content in Brassica vegetables: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(6):823-38. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.688076.

Omoikhoje SO, Aruna MB, Bamgbose AM. Effect of cooking time on some nutrient and antinutrient components of bambaragroundnut seeds. Anim Sci J. 2009 Feb;80(1):52-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2008.00599.x.

Rock CL, Lovalvo JL, Emenhiser C, Ruffin MT, Flatt SW, Schwartz SJ. Bioavailability of beta-carotene is lower in raw than in processed carrots and spinach in women. J Nutr. 1998 May;128(5):913-6.

Shi B, Spallholz JE. Bioavailability of selenium from raw and cooked ground beef assessed in selenium-deficient Fischer rats. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994 Feb;13(1):95-101.

Vermeulen M, Klöpping-Ketelaars IW, van den Berg R, Vaes WH. Bioavailability and kinetics of sulforaphane in humans after consumption of cooked versus raw broccoli. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 Nov 26;56(22):10505-9. doi: 10.1021/jf801989e.

Viadel B, Barberá R, Farré R. Calcium, iron and zinc uptakes by Caco-2 cells from white beans and effect of cooking. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2006 May-Jun;57(3-4):190-7.

Zaheer K, Humayoun Akhtar M. An updated review of dietary isoflavones: Nutrition, processing, bioavailability and impacts on human health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017 Apr 13;57(6):1280-1293. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.989958. Review.

Zhang R, Zhang Z, Zou L, Xiao H, Zhang G, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Enhancing Nutraceutical Bioavailability from Raw and Cooked Vegetables Using Excipient Emulsions: Influence of Lipid Type on Carotenoid Bioaccessibility from Carrots. J Agric Food Chem. 2015 Dec 9;63(48):10508-17. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04691. Epub 2015 Dec 1.