Dr. Ballantyne no longer supports this article. Please see her up-to-date information here.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

There is one diet myth that persists beyond all others, that dietary fat will make you fat and clog your arteries. Not only is dietary fat not bad for you, it’s critical for your health. You need to eat fat in order to absorb vitamins A, D, E, and K (which between them affect every system in your body). Fat is essential for cell construction, nerve function, digestion, and for the formation of the hormones that regulate everything from metabolism to circulation. The membranes of every cell in your body are composed of fat molecules. Your brain is composed of more than 60% fat and cholesterol.

The Paleo framework should settle around roughly balanced macronutrients; 30 to 40% of total calories from fat is a healthy and comfortable zone for many people with 10 to 15% total calories from saturated fat. See Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?

So, let’s review what fats actually are in order to appreciate their importance in a healthy diet for optimal human health.

A Primer on Fatty Acids

Fatty acids, the building blocks of fats, are used not only for energy but also for many basic structures in the human body, such as the outer membrane of every single cell. There are many different fatty acids, each with different effects on, and roles in, human health. A fatty acid has two components. The first is called the hydrocarbon chain, a bunch of hydrocarbons (a carbon atom bonded with one to three hydrogen atoms, the number of which varies for different fats) bonded together in a string, or chain. The second is the carboxyl group, the molecular formula of which is COOH (one carbon atom bound to two oxygen atoms and a hydrogen atom), which is what makes a fatty acid an acid.

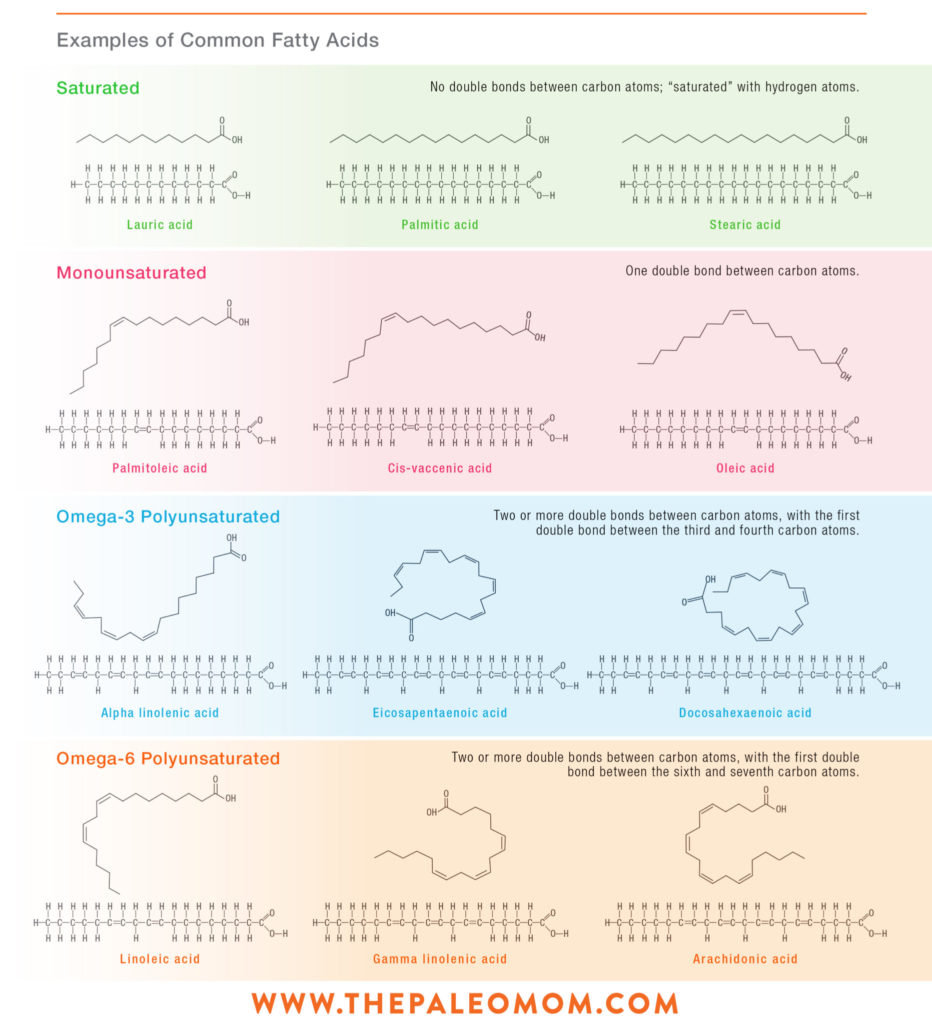

Beyond being categorized based on the length of the hydrocarbon chain, fatty acids are broadly categorized as saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated. These terms reflect the type of molecular bond between the carbons in the hydrocarbon chain (and therefore also the number of hydrogen atoms bound to each carbon atom).

- Saturated fatty acids. A saturated fatty acid is one in which all the bonds between carbon atoms in the entire hydrocarbon chain are single bonds (a simple molecular bond in which two adjacent atoms share a single electron). The carbons are then also “saturated” with hydrogen atoms, meaning that each carbon atom in the middle of the chain is bound to two hydrogen atoms. What’s special about saturated fatty acids is that they are very stable and not easily oxidized (which means they are not prone to react chemically with oxygen). Beyond making saturated fats highly shelf-stable and excellent for even high-temperature cooking, this means that eating them does not contribute to oxidative stress in the body. They are also the easiest for the body to break apart and use for energy. See also Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?

- Monounsaturated fatty acids. A monounsaturated fatty acid is one in which one of the bonds between two carbon atoms in the hydrocarbon chain is a double bond (that is, a molecular bond in which two adjacent atoms share two electrons). This double bond replaces two hydrogen atoms, so the hydrocarbon chain is no longer “saturated” with hydrogen. Monounsaturated fats are less stable than saturated fats and require more enzymes to break apart in order to be used as energy than saturated fats do. See also See 3 Reasons Why Olive Oil is Amazing and Olive Oil Redemption: Yes, It’s a Great Cooking Oil!

- Polyunsaturated fatty acids. A polyunsaturated fatty acid is one in which two or more of the bonds between carbon atoms in the hydrocarbon chain are double bonds (again, replacing hydrogen atoms in the chain). Polyunsaturated fats are easily oxidized, meaning that they are prone to react chemically with oxygen. This reaction typically breaks the fatty acid apart and produces oxidants (free radicals). Consuming oxidized polyunsaturated fats causes oxidative damage to the body. See also Why Vegetable Oils are Bad and The Importance of Fish in Our Diets

Polyunsaturated fats are also broadly categorized as omega-3 fatty acids and omega-6 fatty acids. These classifications relate to the location of the first double bond in relation to the end of the hydrocarbon tail. If the first double bond is between the third and fourth carbon atoms, it’s an omega-3 fatty acid. If it’s between the sixth and seventh, it’s an omega-6 fatty acid.

There are also two essential fatty acids. These rather arbitrarily assigned, yet officially deemed essential fatty acids are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA; the smallest omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid) and linoleic acid (LA; the smallest omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid). The term essential is misleading here. The fatty acids with the most profound roles in the human body are arachidonic acid (AA), an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Our bodies can convert any omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid to any other omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and similarly can convert any omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid to any other omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid—which means that we can make EPA and DHA from ALA and AA from LA. But that conversion can be extremely inefficient, so it’s important to get these from food. While ALA and LA are abundant in plant foods, AA, EPA, and DHA are found in seafood, meat, and poultry.

It’s also worth noting that the body does best when the ratio of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids in our diets is somewhere in the range of 3:1 to 1:1. This is one of the exceptions to the “more is always better” approach to micronutrients. Achieving this ideal ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 requires a fair bit of attention to food choices. Omega-6s are abundant in grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, processed “vegetable” oils (like safflower oil or canola oil), poultry (even organic!), and industrially produced meat (the kind that isn’t labeled “grass-fed” or “pasture-raised”). On the other hand, the extremely important omega-3s DHA and EPA are found in substantial quantities only in grass-fed meat and seafood (mainly fish and shellfish, but sea vegetables and algae also contain some DHA). Balancing the intake of these fats requires both lowering the amount of omega-6-rich foods in our diets and conscientiously including more seafood.

Study after study shows that increasing consumption of DHA and EPA, whether via diet or short-term intervention with fish oil supplements, reduces disease severity and symptoms—for instance, it makes the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis better—and lowers risk of developing certain diseases, such as cardiovascular disease.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

No RDA is established for total fat or individual fatty acids; however, the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) is estimated to be between 20% and 35% of total calories. And, hunter-gatherer intake ranged from 28% to 58% fat.

Balancing Omega-3 to Omega-6

You’ve probably heard a lot about omega-3 fatty acids. That’s because dietary deficiency in omega-3s has been linked to: dyslexia, violence, depression, anxiety, memory problems, Alzheimer’s disease, weight gain, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke, eczema, allergies, asthma, inflammatory diseases, arthritis, diabetes, auto-immune diseases and many others. So, what about omega-6 fatty acids? These are also polyunsaturated fats. Many diet gurus are now labeling linoleic acid (the dominant form of omega-6 found in grains, modern vegetable oils and meat from grain-fed animals) as the True Bad Fat. But, there are no bad fats in nature. The problem is the quantity of omega-6 fats that has insinuated itself into the modern human diet. Ancestral diets consisted of a 1:1 to 1:2 ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids (in some areas, it may have been as high as 1:4). When grain was introduced into the human diet (and to the diets of grazing animals that we raise for food) approximately 10,000 years ago, we started increased the proportion of our dietary fat that is omega-6s. And this has increased even more over the last 100 years, increasing exponentially with the introduction of canola oil into our diets in the mid 1980s). Modern Western diets contain anywhere from a 1:10 to a 1:40 ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids. This is NOT what nature intended for our optimal health. See also Why Vegetable Oils are Bad and Trans Fats: What Are They, and Why Are They Bad?

The ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fats is important because these two types of fat compete for many of the same functions in the body. In particular, the omega-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid (AA) competes against the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA. Depending on which type of fat “wins,” the effect is different. Within the outer membrane of every cell, various fatty acids and proteins are embedded, such as cholesterol molecules, receptors, and, yes, AA, DHA, and EPA. When incorporated into the membrane, DHA and EPA affect cell membrane properties, such as fluidity, flexibility, and permeability, and alter the activity of enzymes that are embedded in the membrane. These effects are beneficial to the health and function of the cell. And when needed, AA, DHA, and EPA can be internalized and metabolized into important signaling molecules (akin to short-distance hormones), called prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes, that control a variety of functions, including inflammation, clotting, vascular function and health, pain signaling, cell growth, kidney function, and stomach acid secretion.

When diets contain predominantly omega-6 fatty acids, there is far more AA than DHA and EPA in the cell membranes. However, when diets are supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids, DHA and EPA can readily replace AA in the membranes of practically all cells. This is important because the prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes produced from AA are far more inflammatory and have other negative effects, like increasing pain, increasing thrombosis (clots forming in blood vessels, which can lead to things like deep vein thrombosis, stroke and ischemic heart disease), and constricting blood vessels, which increases blood pressure. This is why fish oil supplements have proven so effective at reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors and reducing pain from diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

The omega-3s that our bodies really need are DHA and EPA. The shorter-chain omega-3 fatty acid ALA, which is found in flax seeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, is not easily used by the body because it must first be converted to DHA or EPA, which is a very inefficient process. A 3½-ounce serving of oily coldwater fish like wild-caught salmon, sardines, albacore tuna, trout, or mackerel has more than 500 milligrams of DHA and EPA. Fish containing moderate amounts of DHA and EPA (150 to 500 milligrams per 3½-ounce serving) include most whitefish like bass, cod, haddock, hake, halibut, flounder, perch, and sole, as well as farmed salmon. Crab, oysters, and shrimp contain moderate amounts of DHA and EPA as well.

Why not just get DHA and EPA from fish oil supplements? These polyunsaturated fats are easily oxidized in response to heat or light and are not very shelf-stable, especially once isolated. Consuming oxidized omega-3 fats contributes to inflammation as opposed to reducing it. In fresh, frozen, or canned whole fish, the omega-3 fats are protected from oxidation, plus fish provides all the necessary cofactors for optimal absorption and use by the body.

Important Healthy Fats

DHA (docosahexaenoic acid): An omega-3 fatty acid that is abundant in the brain and retinas and plays a role in maintaining normal brain function, treating mood disorders, and reducing risk of heart disease (or improving outcomes for people who already have it). The richest sources are fatty fish, such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, herring, and sardines. See The Importance of Fish in Our Diets, Should We Be Worried About Radiation from Fukushima?, The Mercury Content of Seafood: Should we worry? and Oysters, Clams, and Mussels, Oh My! Nutrition Powerhouses or Toxic Danger?

EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid): An omega-3 fatty acid that plays a role in anti-inflammatory processes and the health of cell membranes and may help reduce symptoms of depression. Sources include fatty fish (such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, herring, and sardines), purslane, and algae.

CLA (conjugated linoleic acids): A family of naturally occurring trans fatty acids that exhibit strong anticancer effects and may improve bone density and increase muscle mass. CLAs are found in ruminant meat, such as beef, lamb, elk, and goat, as well as dairy from grass-fed animals. See Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA): A Rockstar Nutrient and Goat Milk: The Benefits of A2 Dairy

Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA): A type of fat that may help reduce LDL (“bad”) cholesterol while potentially increasing HDL (“good”) cholesterol and help improve blood sugar control. Foods rich in MUFA include olives, tree nuts like almonds, avocados, and seeds. See 3 Reasons Why Olive Oil is Amazing and Olive Oil Redemption: Yes, It’s a Great Cooking Oil!

Fat in Moderation

As mentioned, the Paleo framework should settle around roughly balanced macronutrients; 30 to 40% of total calories from fat is a healthy and comfortable zone for many people with 10 to 15% total calories from saturated fat. See Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers, The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies? and Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?. However, with the false equivalency of low-carb or ketogenic diets with the Paleo diet, many people are going All In with dietary fat. It’s important to emphasize here that moderate fat intake is very healthful, but there are some ligitimate problems with high fat intake, discussed in Saturated Fat: Healthful, Harmful, or Somewhere In Between?. In addition, healthy, slow-burning carbohydrates are still a vital component of a health-promoting diet, so problems arise when fat intake gets too high at the expense of carbohydrate intake. See The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s Non-Metabolic Roles in the Human Body, How Many Carbs Should We Eat?, and Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised.