An herbivore eats plants. A carnivore eats meat. An omnivore eats both plants and meat. So, what is a Nutrivore? Nutrivore is the revolutionary yet simple dietary concept: Choose foods to meet the body’s nutritional needs.

Nutrivore

no͝ o-trĭ-vôr’

noun

What makes the concept of Nutrivore so revolutionary? Despite the long-established Recommended Daily Intake of essential nutrients and increasing awareness of the importance of non-essential nutrients (like CoQ10 and polyphenols), no mainstream diet has ever integrated the concept of nutrient sufficiency, meaning we get all of the essential and non-essential nutrients our bodies need to thrive from the foods we eat. The notable exception in the Autoimmune Protocol, the dietary tenets of which are based on nutrient-dense foods as the foundation.

As a society, we’re fairly used to thinking about how food is related to weight: eat too much of the wrong things and you become overweight; eat the right amounts of the right things and you lose weight. But health is about so much more than weight, and in actuality how much you weigh is a pretty poor indicator of health (see Can You Really Be Healthy at Any Size?, TWV Podcast Episode 436: What Is Health, and How Do You Measure It?, TWV Podcast Episode 471: The Harm of Weight Discrimination and Stigma – Part 1 and TWV Podcast Episode 472: The Harm of Weight Discrimination and Stigma – Part 2). And food has a much more profound impact on health than whatever the number is on the scale.

Where Most Diets Fail

Where Most Diets Fail

As I discussed in The Importance of Nutrient Density, micronutrient deficiencies are so common that some researchers speculate that at least 90% of us of us are deficient in at least one vital nutrient. Our food system is abundant in calories (the U.S. produces about 6,000 calories’ worth of food per person per day), but the Standard American Diet is deficient in most of the essential vitamins and minerals that our bodies need to be healthy. In fact, multiple analyses of food intakes have shown that large percentages of Americans routinely consume inadequate amounts of essential vitamins and minerals. In fact, up to

- 56% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin A

- 28% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B1 (thiamin)

- 22% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B2 (riboflavin)

- 24% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B3 (niacin)

- 54% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B6 (pyridoxine)

- 75% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B9 (folate)

- 30% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin B12 (cobalamin)

- 48% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin C (ascorbate)

- 94% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin D

- 89% of Americans don’t consume enough vitamin E

- 92% of Americans don’t consume enough choline

- 73% of Americans don’t consume enough calcium

- 31% of Americans don’t consume enough copper

- 39% of Americans don’t consume enough iron

- 68% of Americans don’t consume enough magnesium

- 21% of Americans don’t consume enough phosphorous

- 100% of Americans don’t consume enough potassium

- 15% of Americans don’t consume enough selenium

- 73% of Americans don’t consume enough zinc

- 70% of Americans don’t consume enough omega-3 fats

- 90% of Americans don’t consume enough fiber

- 90% of Americans don’t consume enough polyphenols

Junk food, white bread, and high-fructose corn syrup aren’t the only culprits here. Even eating what many people believe to be a healthy whole-foods diet can leave our bodies starved for micronutrients. And this falls on the shoulders of dietary guidelines. Analyses of USDA dietary guidelines reveal common micronutrient deficiencies, including: vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, calcium, iodine, magnesium, potassium, zinc and omega-3 fats. And, the biggest reason for these nutrient shortfalls is the promotion of grains as a foundational food, despite the fact that even whole grains don’t contribute much more than calories and fiber to our diets (see also Gluten-Free Diets Can Be Healthy for Kids).

Junk food, white bread, and high-fructose corn syrup aren’t the only culprits here. Even eating what many people believe to be a healthy whole-foods diet can leave our bodies starved for micronutrients. And this falls on the shoulders of dietary guidelines. Analyses of USDA dietary guidelines reveal common micronutrient deficiencies, including: vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, calcium, iodine, magnesium, potassium, zinc and omega-3 fats. And, the biggest reason for these nutrient shortfalls is the promotion of grains as a foundational food, despite the fact that even whole grains don’t contribute much more than calories and fiber to our diets (see also Gluten-Free Diets Can Be Healthy for Kids).

Unfortunately, diet alternatives to the USDA dietary guidelines (whether fad or based in some legit science, see Autoimmune Protocol Clinical Trials and Studies and Paleo Diet Clinical Trials and Studies) aren’t much of an improvement from a nutrient sufficiency standpoint and some have exacerbated the nutrient deficiency problem either through a lack of a nutrient focus and education or by omitting groups of nutritious whole foods, in some cases eliminating all food sources of certain nutrients.

For example, the standard Paleo diet is structured around avoiding grains, legumes and dairy (of course, this is not my approach, see also Ditching Diet Dogma, The Paleo Template e-book, and Paleo Principles). Vegan diets avoid meat and dairy (see also Plant-Based Protein: What is its Role in the Paleo Diet? and TWV Podcast Episode 435: Is Protein from Vegetables Enough?). Low-carb and ketogenic diets limit the amount of carbohydrates you eat (which, I have criticized in Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets: Caution Advised, How Ketogenic Diet Wreaks Havoc on Your Gut, Paleo, Resistant Starch, and TMAO: New Study Warning Worth Heeding, The Case for More Carbs: Insulin’s NonMetabolic Roles in the Human Body and How Many Carbs Should We Eat?). And low-fat diets limit the amount of dietary fat you eat (which I have also criticized in Carbs Vs. Protein Vs. Fat: Insight from Hunter-Gatherers). And many weight loss diets are centered around caloric restriction.

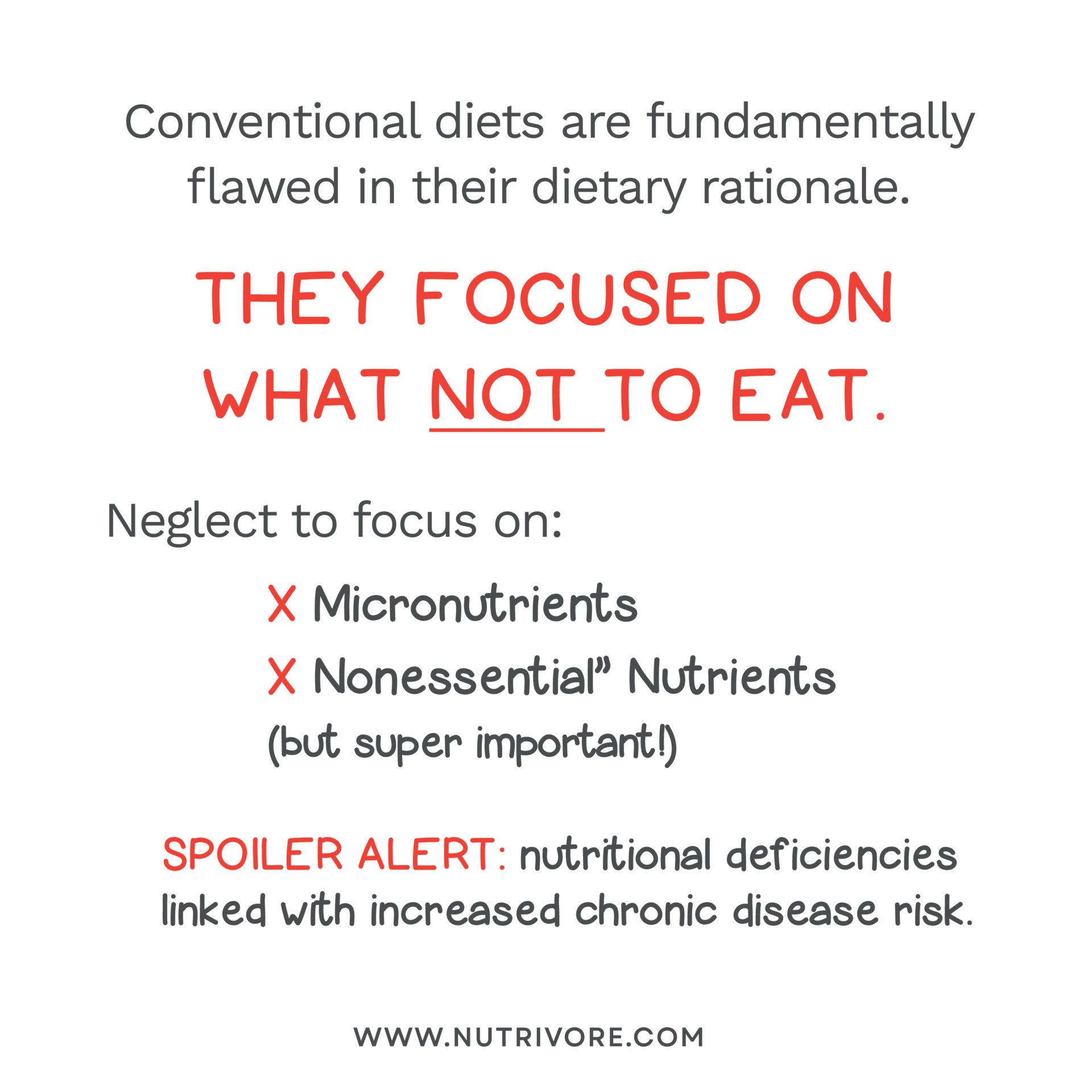

What do all of these diets have in common? Because they are all focused on what not to eat, they don’t teach how to choose foods based on the nutrients they contain. In fact, these diets focus on just about everything but nutrients, especially micronutrients but also nonessential (but super important) nutrients, representing a fundamental flaw in each dietary rationale. Instead, these popular diet plans teach an oversimplification of nutritional sciences or even a complete disregard for all scientific research that doesn’t conform to a diet’s preconceived notions. (See also The History of Dietary Guidelines (and How They’ve Steered Us Wrong))

What do all of these diets have in common? Because they are all focused on what not to eat, they don’t teach how to choose foods based on the nutrients they contain. In fact, these diets focus on just about everything but nutrients, especially micronutrients but also nonessential (but super important) nutrients, representing a fundamental flaw in each dietary rationale. Instead, these popular diet plans teach an oversimplification of nutritional sciences or even a complete disregard for all scientific research that doesn’t conform to a diet’s preconceived notions. (See also The History of Dietary Guidelines (and How They’ve Steered Us Wrong))

The result is that these popular diets purported to improve health or facilitate weight loss all fall short of the mark because nutritional deficiencies linked with increased chronic disease risk are still common among adopters. For example:

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

- Vegan and vegetarian diets are commonly deficient in vitamin A, vitamin B3, vitamin B9, vitamin B12, calcium, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, magnesium, manganese, zinc and omega-3 fats.

- Low-carb diets are commonly deficient in vitamin B2, vitamin B5, vitamin B6, vitamin B9, vitamin D, vitamin E, biotin, choline, calcium, chromium, iodine, iron, magnesium, molybdenum, potassium, zinc and fiber.

- Low-fat diets are commonly deficient in vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin K, calcium and omega-3 fats.

- Calorie-restriction programs are commonly deficient in vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B3, vitamin C, vitamin E, calcium, iron, magnesium, potassium and zinc.

- Gluten-free diets are commonly deficient in vitamin D, vitamin B3, vitamin B9, vitamin B12, iron, magnesium, calcium, zinc and fiber.

- Paleo and primal diets (at least how you would learn about them from other thought leaders) are commonly deficient in biotin, calcium and chromium.

- Ketogenic diets are commonly deficient in vitamin A, vitamin B2, vitamin B5, vitamin B6, vitamin B9, vitamin E, vitamin D, vitamin K, biotin, choline, calcium, chromium, choline, iodine, iron, magnesium, molybdenum, potassium, selenium zinc and fiber.

In fact, no popular branded or fad diet achieves nutrient sufficiency because nutrient-awareness is not integrated into their dietary frameworks, which is why the concept of Nutrivore is so important. As already mentioned, the two notable exceptions are: 1) the Autoimmune Protocol, which promotes nutrient-dense superfoods—organ meat, seafood, and tons of veggies—as the foundation of the diet with recommendations for nutrient tracking to ensure nutrient sufficiency; and 2) the way I teach the Paleo diet which incorporates Nutrivore tenets (see Paleo Principles, The Paleo Template E-Book, and the Therapeutic Paleo Approach online course). And this could be replicated by other dietary templates.

The good news is that most popular and fad diets are compatible with Nutrivore by overlaying an emphasis on nutrient-sufficiency overtop of the core dietary structure. By carefully selecting a wide variety of foods such that the body’s nutrient requirements are met by the diet, the most basic function of diet is achieved—nourishment!

Choosing Foods Based on Nutrients

Nutrients are those substances within the foods we eat that provides nourishment essential for growth and the maintenance of life. Every cell, tissue, organ, and system in the human body needs specific amounts of select nutrients in order to function efficiently and effectively. Nutrients are used not only in the formation the components of our bodies but also in the millions of chemical reactions that occur in our bodies in every moment. We are made of nutrients and our bodies need them to do even basic things like breathing.

Every tiny detail of every function of every part of the human body requires nutrients, which can be broadly categorized as macronutrients, those we need in large quantities, and micronutrients, those we need in smaller quantities.

- Macronutrients — protein, fat, and carbohydrates — supply the energy that fuels the complex functions of life along with being basic building blocks for cellular structures.

- Micronutrients — vitamins, minerals, plant phytonutrients, and other compounds — can also be incorporated into cellular structures, but more commonly are necessary resources that facilitate or get used up in cellular chemical reactions.

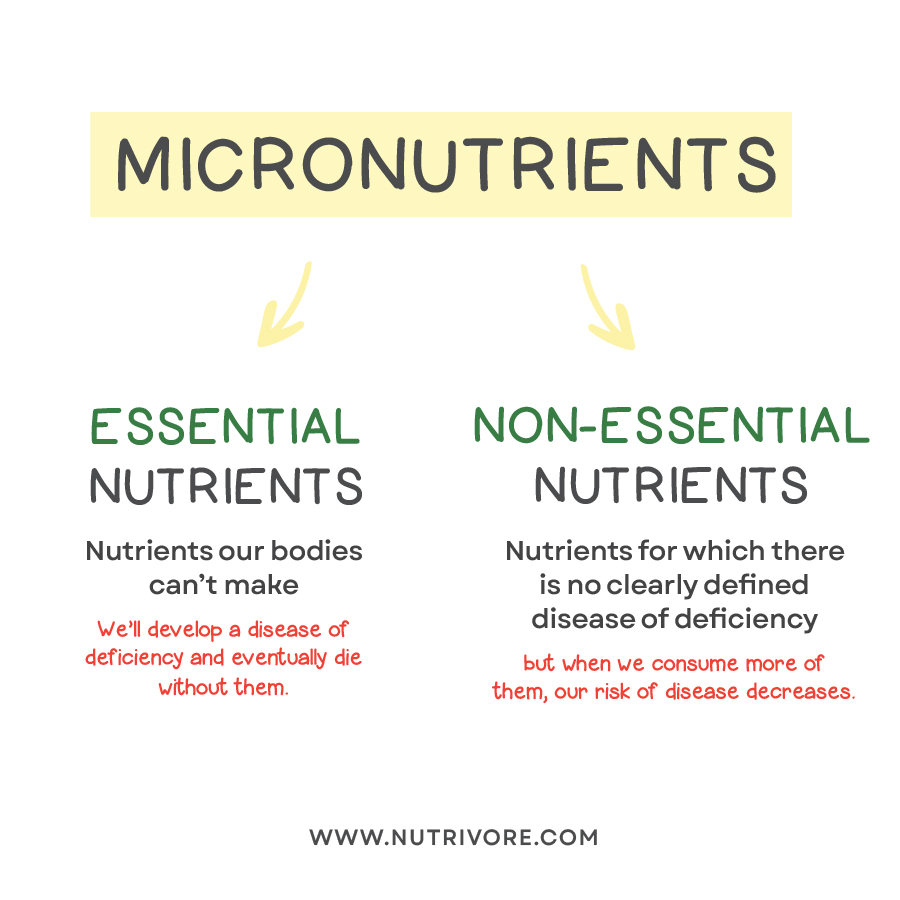

Micronutrients can be categorized as essential and nonessential. Essential nutrients are those that our bodies can’t make– we’ll develop a disease of deficiency and eventually die without them. Because diseases of deficiency can be studied in detail, it is easy to establish Recommended Daily Intake levels of essential nutrients, the minimum amount of that specific nutrient needed to meet the nutritional needs of 97.5% of the population (the remaining 2.5% needing more). Being even slightly deficient in a single essential nutrient can have negative consequences for our health. In contrast, nonessential nutrients are those for which there is no clearly defined disease of deficiency—we’ll go on living without them, perhaps because our body can synthesize them to some degree, though we may not be particularly healthy if we don’t get enough. Indeed, many nutrients that are considered nonessential are known to improve health the more of them we eat.

Micronutrients can be categorized as essential and nonessential. Essential nutrients are those that our bodies can’t make– we’ll develop a disease of deficiency and eventually die without them. Because diseases of deficiency can be studied in detail, it is easy to establish Recommended Daily Intake levels of essential nutrients, the minimum amount of that specific nutrient needed to meet the nutritional needs of 97.5% of the population (the remaining 2.5% needing more). Being even slightly deficient in a single essential nutrient can have negative consequences for our health. In contrast, nonessential nutrients are those for which there is no clearly defined disease of deficiency—we’ll go on living without them, perhaps because our body can synthesize them to some degree, though we may not be particularly healthy if we don’t get enough. Indeed, many nutrients that are considered nonessential are known to improve health the more of them we eat.

Often, micronutrients are called nonessential simply because we don’t really understand exactly what it does in our bodies to support health—we just know that when we consume more of it, our risk of disease decreases. This is the case for most phytonutrients (like polyphenols and carotenoids) and many vitaminlike compounds (like coenzyme Q10 and choline). There are thousands of plant phytonutrients, and our understanding of their roles in health is so rudimentary that the most we can typically say about them is that they have antioxidant activity (that is, they help prevent damage to molecules in our body from oxidation). Yet we know that the more plant phytonutrients in our diet, the lower our risk of chronic and infectious disease. When you think about it in these terms, it’s easy to realize that even nonessential nutrients are pretty darned important.

Our macronutrient and micronutrient stores must be continuously topped up from the foods we eat. Unfortunately, getting all of our required nutrients from food is easier said than done. Many of the staple foods of the typical American diet have very little nutritional value. Even worse, the more a food is refined and processed and manufactured, the more the nutrients inherent to the raw ingredients are leached out, removed, or degraded. Processed foods, refined foods, fast food, and junk food all contribute next to no nutrients to our diets (plus, they’re often problematic for our health in other ways). But even foods that many people think are healthy, like whole grains and low-fat dairy, are pretty weak when it comes to essential nutrients. And every time a nutritionally weak food displaces a nutritional powerhouse, the overall nutritional value of the diet suffers.

Here is where becoming a Nutrivore comes in.

What Is Nutrivore?

What Is Nutrivore?

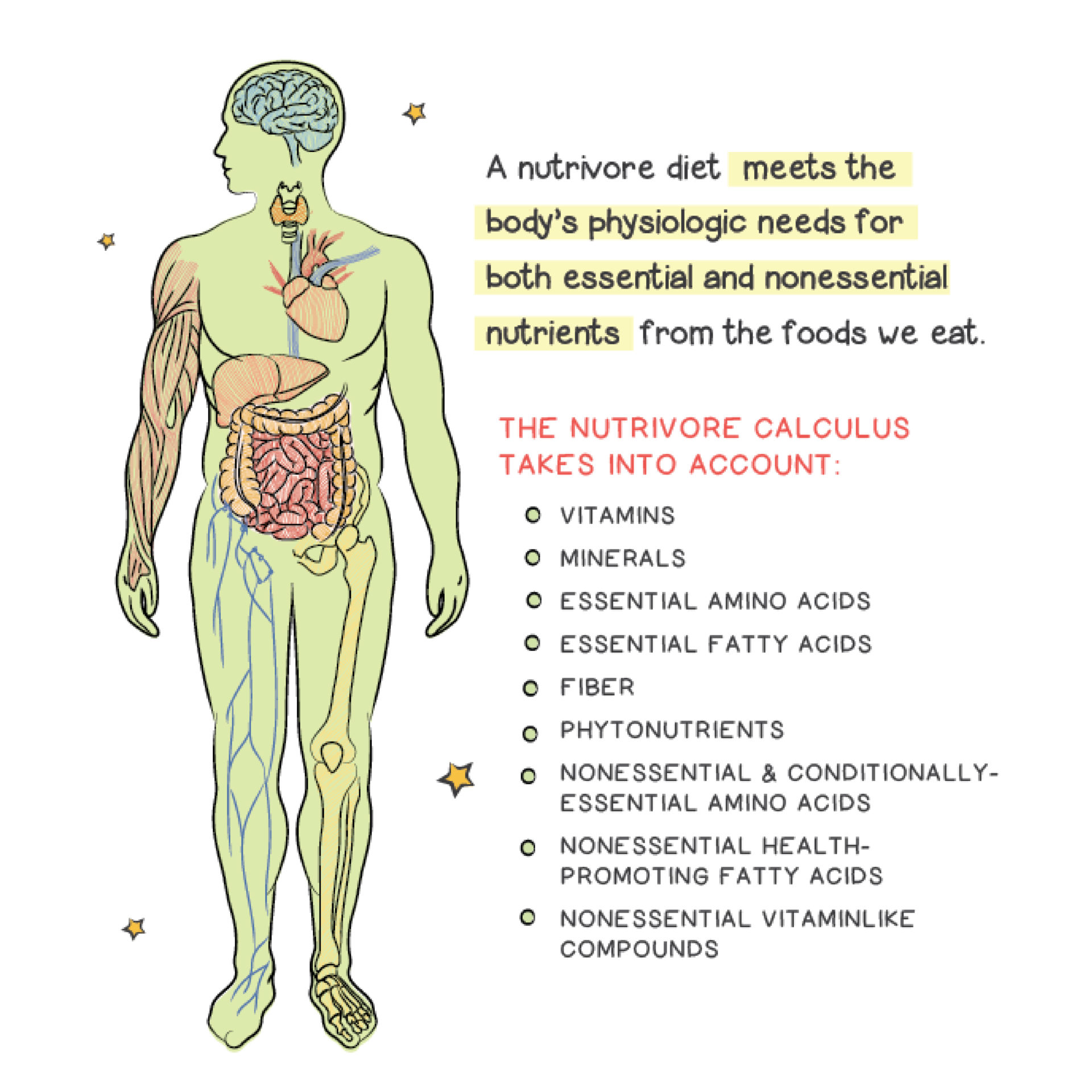

A Nutrivore diet is one in which the goal is to fully meet the body’s physiologic needs for both essential and nonessential nutrients from the foods we eat, also called nutrient sufficiency, but without consuming excess energy (i.e., staying within daily caloric requirements). By including not only the full cadre of essential nutrients but also fiber, phytonutrients, nonessential and conditionally-essential amino acids (like glutamine and arginine), nonessential health-promoting fatty acids (like DHA, EPA and CLA), and nonessential vitaminlike compounds into the nutrition calculus, we are ensuring both nutrient synergy as well as prioritizing the full complement of nutrients our bodies need to thrive.

Being a Nutrivore is about the overall quality of the whole diet, and not about a list of yes-foods and no-foods. Even though eliminating empty calorie foods helps to achieve nutrient sufficiency without overeating, no food is strictly verboten. In this way, being a Nutrivore is a diet modifier rather than a diet itself—a nutrivorous approach can be layered atop of other dietary structures and priorities in order to meet an individual’s specific health needs and goals.

For example, you can follow a Nutrivore Paleo diet (as I teach in see Paleo Principles, The Paleo Template E-Book, and the Therapeutic Paleo Approach online course), or a Nutrivore Mediterranean diet, or a Nutrivore whole-foods diet, or a Nutrivore plant-based diet, or a Nutrivore Autoimmune Protocol (well, that last one should be a given). You can also apply the Nutrivore philosophy to anti-diet culture, and in fact, it’s completely aligned with the body positivity movement (see also TPV Podcast Episode 358: How Intuitive Eating Has It Wrong).

Even though some individuals may still need to eliminate food sensitivities that trigger reactions or chronic disease symptoms (as in the AIP), or may choose to eliminate certain foods to conform to a specific dietary structure (as in Paleo), this in no way prevents us from achieving nutrient sufficiency, although it may necessitate thoughtful selection from the included foods. Only extreme diets that eliminate all sources of specific nutrients—such as a carnivore diet, fruitarian diet, and some implementations of a ketogenic diet—are incompatible with being a Nutrivore.

Rule #1 of Nutrivore: Choose a Variety of Nutrient-Dense Foods

Because there’s no such thing as a nutritionally complete food or food group, there’s no single food that provides all of the nutrients we need to thrive. (As an aside, very few animals survive exclusively or almost exclusively on a single food. And, for example, giant pandas have to eat about 83 pounds of bamboo shoots, leaves and stems every day to meet their nutritional needs!) As an extreme example, what if you decided to only eat watercress because its the single most nutrient-dense food? Well, you’d get crazy amounts of vitamin C, vitamin K, carotenoids and glucosinolates, and if you ate enough of it (285 cups of watercress would get you to 2000 calories), you could reach the RDA of most vitamins and minerals. But, you’d still be lacking in vitamin D, vitamin B12, choline, omega-3 fats, and some essential amino acids, especially methionine and tryptophan. You’d also miss out on the full diversity of polyphenols as well as some functional compounds that just aren’t available in watercress, like taurine, carnitine, carnosine, creatine, ergothioneine and thiosulfinates.

Ultimately, there are nutrients we can get only from plant foods and nutrients we can get only from animal foods: We need both to obtain the full complement of nutrients that our bodies need to be healthy. See The Diet We’re Meant to Eat, Part 3: How Much Meat versus Veggies?

The most straightforward way to ensure that our diet is abounding in nutrients is to choose nutrient-dense superfoods more often. That means that the more we can fill our plates with vegetables, fruits, and mushrooms and choose fish, shellfish or organ meat for our proteins, seasoning liberally with herbs and spices, and use superfoods like nuts and seeds as condiments, the higher the nutritive quality of our overall diet, which makes room for some lower nutrient-density foods without sacrificing the goal of achieving nutrient sufficiency!

The most straightforward way to ensure that our diet is abounding in nutrients is to choose nutrient-dense superfoods more often. That means that the more we can fill our plates with vegetables, fruits, and mushrooms and choose fish, shellfish or organ meat for our proteins, seasoning liberally with herbs and spices, and use superfoods like nuts and seeds as condiments, the higher the nutritive quality of our overall diet, which makes room for some lower nutrient-density foods without sacrificing the goal of achieving nutrient sufficiency!

It’s important thing to emphasize that following a Nutrivore approach isn’t about perfection. With there being no foods that are strictly off-limits (unless you have an allergy or intolerance, of course), we can take a step back from diet dogma. In fact, because we are able to store at least a modest amount of most nutrients, the goal isn’t even nutrient sufficiency for the whole diet on a daily basis, but rather nutrient sufficiency on average. It’s okay if you don’t reach the RDA for zinc one day; but, it’s a good idea to troubleshoot and find a way to incorporate more zinc-rich foods into your diet if you find yourself falling short most days. Apps like Cron-o-meter can help you easily see if you’re meeting the RDA of essential vitamins and minerals, eating enough fiber, and getting enough omega-3 fats. Try keeping a food journal for a few days to identify if there are any nutrients you’re routinely falling short on, then figure out what foods you can add to your diet to better meet your nutritional needs.

Introducing Nutrivore.com

Introducing Nutrivore.com

I’m so excited to start sharing details about the new website I’ve been building for about a year and a half: Nutrivore.com! I’m building this website outside of any dietary dogma. Being a Nutrivore is about the overall quality of the whole diet, and not about a list of yes-foods and no-foods. Even though eliminating empty calorie foods helps to achieve nutrient sufficiency without overeating, no food is strictly off-limits. In this way, being a Nutrivore is a diet modifier rather than a diet itself—a Nutrivore approach can be layered atop of other dietary structures and priorities in order to meet an individual’s specific health needs and goals.

I see Nutrivore as the natural extension of my science-grounded approach, and one that will allow me to both level up the depth of my resources for my long-time readers who love my science deep dives, but also meet people where they are and embrace the idea that even a small first step is worth celebrating. (See also Ditching Diet Dogma, My Personal Journey with the Autoimmune Protocol and My Personal Journey as a Blogger).

My vision for Nutrivore.com is extremely ambitious: A detailed educational resource devoid of dietary dogma and instead purely based on scientific studies and nutrient profiling to quantify nutrient density, all with the goal of helping people achieve dietary nutrient sufficiency (a.k.a. Nutrivore) through informed day-to-day choices.

I’ll be launching Nutrivore.com in November (fittingly enough, my 10-year blogging anniversary plus my birthday month!) with a ton of content, and then continuing to add articles regularly afterwards to build the most comprehensive nutrition- and health-focused website ever created.

Last year, I released my gut microbiome e-books, The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook, the culmination of over six years of intense research and writing. Even longer, more detailed versions of both of these books are still in the works for upcoming in-print books that were delayed due to covid-19.

Last year, I released my gut microbiome e-books, The Gut Health Guidebook and The Gut Health Cookbook, the culmination of over six years of intense research and writing. Even longer, more detailed versions of both of these books are still in the works for upcoming in-print books that were delayed due to covid-19.

When I decided to wade into the scientific literature on the gut microbiome, and specifically the intersection between diet and lifestyle and supporting a healthy and happy community of gut microbes, I decided the only way to do this right was to leave all of my previously established conclusions about which foods are good or bad at the door. No diet dogma allowed! As I read and learned and compiled information, maintaining an open mind to follow the science wherever it led, I realized that a very important tool was missing, a way to define and quantify nutrient density. It’s one thing to say “eat more nutrient-dense foods”, but how do we even identify what foods qualify?

When I completed The Gut Health e-books, my next project was to start developing the foundational content for Nutrivore.com. I knew that I needed a method to quantify the nutrient density of foods, meaning a score that represents how much nutrients a food contains — the higher the number, the more nutrients per calorie. This is actually a field of research called nutrient profiling, the science of categorizing foods according to their nutritional composition.

My initial plan was to comb through the research and choose one of the dozen or so existing nutrient density scores to use. After reading through nearly every nutrient profiling study ever published (which took me about two months!), I reached a disappointing conclusion: Every nutrient density score that had been developed thus far was flawed. How flawed? Just one example is scores that utilize just a few select nutrients in the calculations in order to best align with the USDA dietary guidelines. The rationale is that some nutrients are more strongly correlated with health outcomes than others, but ignores the fact that these “important” nutrients are typically the ones we’re most deficient in, rather than any special property of the nutrient itself. The biggest problem with this approach is the idea of retrofitting to guidelines that were not crafted with nutrient density or sufficiency in mind! This is backwards! We should be aligning dietary guidelines with insight from nutrient profiling, not the other way around!

So, I did the only logical thing I could do. I spent the next six months developing my own nutrient profiling method, which I call the Nutrivore Score! It’s currently (IMO) the most comprehensive, and least bias, method for representing the inherent nutrient content of foods, borne out of a confusing array of similar, yet all flawed, nutrient density scores, while recognizing the current limitations posed by incomplete data. To date, I have calculated the Nutrivore Score for nearly 300 foods. And wow, were there ever some surprises! Some foods scored way lower than I expected, others much higher, and I’ve realized that the Nutrivore Score is a critically important tool for informing day-to-day food choices. Combining the insight I gleaned from my gut microbiome research with nutrient profiling via the Nutrivore Score has led me to see many foods in a new light. I’ve made changes to my family’s and my diet as a result.

So, I did the only logical thing I could do. I spent the next six months developing my own nutrient profiling method, which I call the Nutrivore Score! It’s currently (IMO) the most comprehensive, and least bias, method for representing the inherent nutrient content of foods, borne out of a confusing array of similar, yet all flawed, nutrient density scores, while recognizing the current limitations posed by incomplete data. To date, I have calculated the Nutrivore Score for nearly 300 foods. And wow, were there ever some surprises! Some foods scored way lower than I expected, others much higher, and I’ve realized that the Nutrivore Score is a critically important tool for informing day-to-day food choices. Combining the insight I gleaned from my gut microbiome research with nutrient profiling via the Nutrivore Score has led me to see many foods in a new light. I’ve made changes to my family’s and my diet as a result.

It is time for a positive approach to dietary guidance using nutrient density as a basic principle. The Nutrivore Score is a necessary foundational step towards achieving this goal! By understanding the nutrients per calorie offered by individual foods via the Nutrivore Score, in addition to recognition that certain nutrients are exclusive to specific food groups, we can achieve nutrient sufficiency by choose a variety of nutrient-dense superfoods as well as the highest Nutrivore Score options from the various foundational food groups.

Grab My Nutrivore Score Guide to Food Groups

I’ll be sharing more details on the Nutrivore Score in an upcoming article, but right now, you can get my Nutrivore Score Guide to Food Groups in your inbox for free! Simply sign up below!

"*" indicates required fields