SCIENCE SIMPLIFIED:

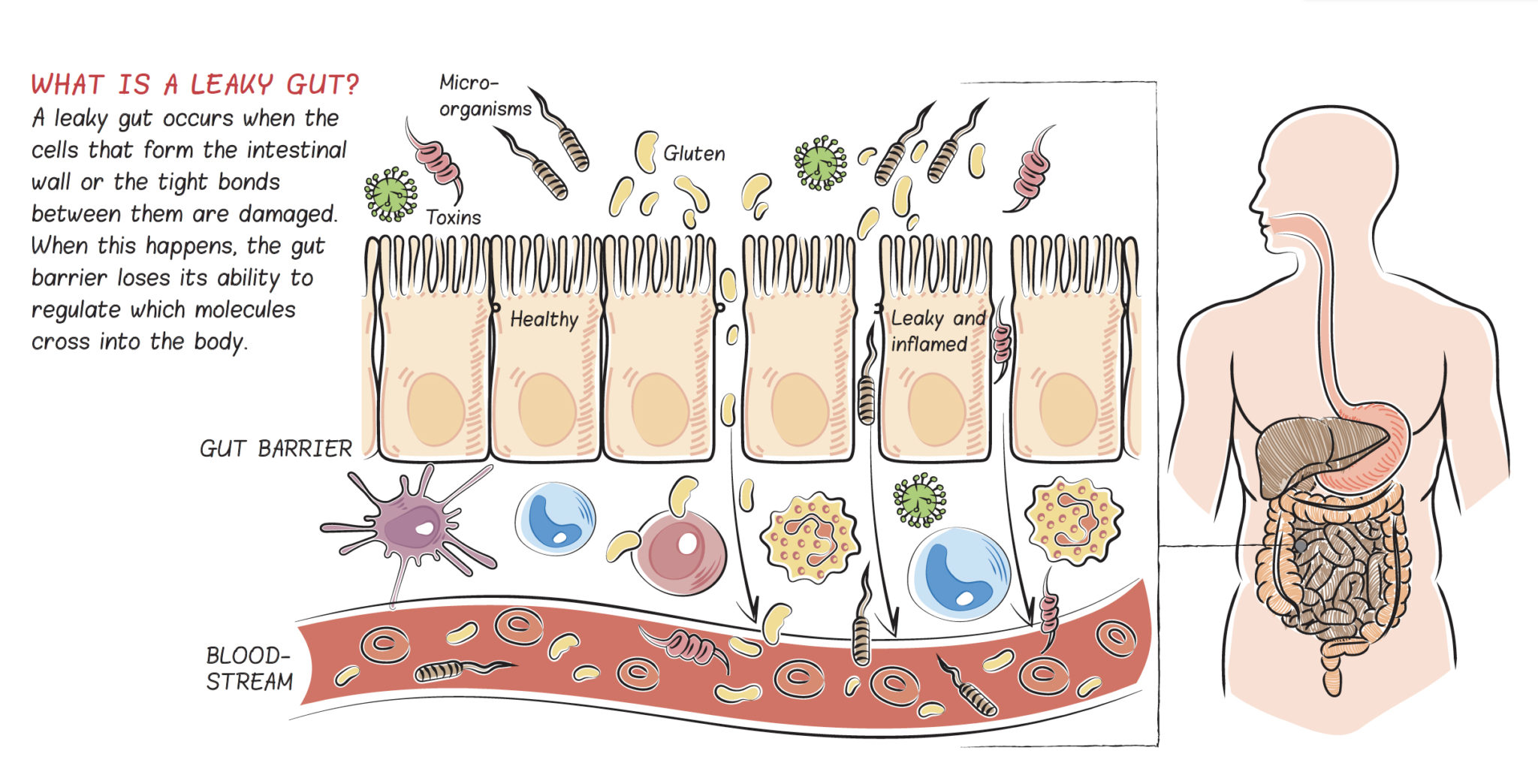

- The gut barrier is a specialized semi-permeable barrier. It’s supposed to let nutrients into the body while keeping everything else out.

- Increased intestinal permeability (colloquially referred to as “leaky gut”) refers to loss of gut barrier integrity such that substances can cross (or “leak”) into the body that normally wouldn’t (or in higher quantities than normal)

- Immediately inside the gut barrier is 80% of our immune systems, so when substances (like bacterial proteins, partially digested food particles, and toxins) cross into the body, the immune system is activated

- The immune activation that results from increased intestinal permeability causes systemic (body-wide) inflammation that is associated with all chronic illnesses

- A huge variety of symptoms and diagnoses can point to a “leaky gut”

RELATED READING:

- 8 Nutrients for Leaky Gut

- What Should You Eat To Heal a Leaky Gut?

- Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut

- Which Comes First: the Leaky Gut or the Dysfunctional Immune System?

One of the fundamental principles of the Paleo diet is avoiding foods that damage the lining of the gut, contributing to “leaky gut”. Is this just the latest catch-phrase? While the term leaky gut is becoming popular in some circles, it is also lumped into a category with “divining allergies” and “balancing chakras” by some medical professionals. However, the body of scientific literature showing that increased intestinal permeability is inextricably linked to diverse diseases is convincing. Even though there is no difference between them, you may get taken more seriously by medical professionals if you say “increased intestinal permeability” instead of “leaky gut.”

What Is the Gut?

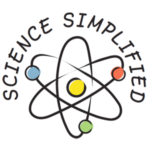

Gut is the colloquial term for the gastrointestinal tract (also called the GI tract, digestive tract, digestive tube, or gastrointestinal system), an organ system composed of the esophagus, the stomach and both the small and large intestines. The gut is a major component of the digestive system—a greater organ system composed of the entire gut as well as the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, tongue and salivary glands—responsible for digesting the foods we eat, absorbing nutrients, and expelling waste.

The foods we eat are digested inside the gut as they travel from one end to the other. Digestion is the chemical and mechanical breakdown of foods into small molecules, or nutrients, that can be absorbed into the body. Nutrients, the many substances essential for growth and the maintenance of life, consist of a diversity of chemicals: amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins; fatty acids, which are the building blocks of fat but also a critical component of every cell’s membranes; monosaccharides, which are the simplest carbohydrates and which our bodies use for energy; vitamins and vitaminlike compounds, which are used in a vast range of chemical reactions in our bodies; minerals, which are important building blocks for many structures in the human body in addition to facilitating chemical reactions, nerve conduction, and electrolyte balance; and phytochemicals, which are important antioxidants and which are also used in chemical reactions. Fiber is also an important nutrient, but not because it’s absorbed into our body. Instead, fiber feeds the bacteria that live in the small and large intestine, supporting the health of this microbial community, collectively referred to as the gut microbiota.

The foods we eat are digested inside the gut as they travel from one end to the other. Digestion is the chemical and mechanical breakdown of foods into small molecules, or nutrients, that can be absorbed into the body. Nutrients, the many substances essential for growth and the maintenance of life, consist of a diversity of chemicals: amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins; fatty acids, which are the building blocks of fat but also a critical component of every cell’s membranes; monosaccharides, which are the simplest carbohydrates and which our bodies use for energy; vitamins and vitaminlike compounds, which are used in a vast range of chemical reactions in our bodies; minerals, which are important building blocks for many structures in the human body in addition to facilitating chemical reactions, nerve conduction, and electrolyte balance; and phytochemicals, which are important antioxidants and which are also used in chemical reactions. Fiber is also an important nutrient, but not because it’s absorbed into our body. Instead, fiber feeds the bacteria that live in the small and large intestine, supporting the health of this microbial community, collectively referred to as the gut microbiota.

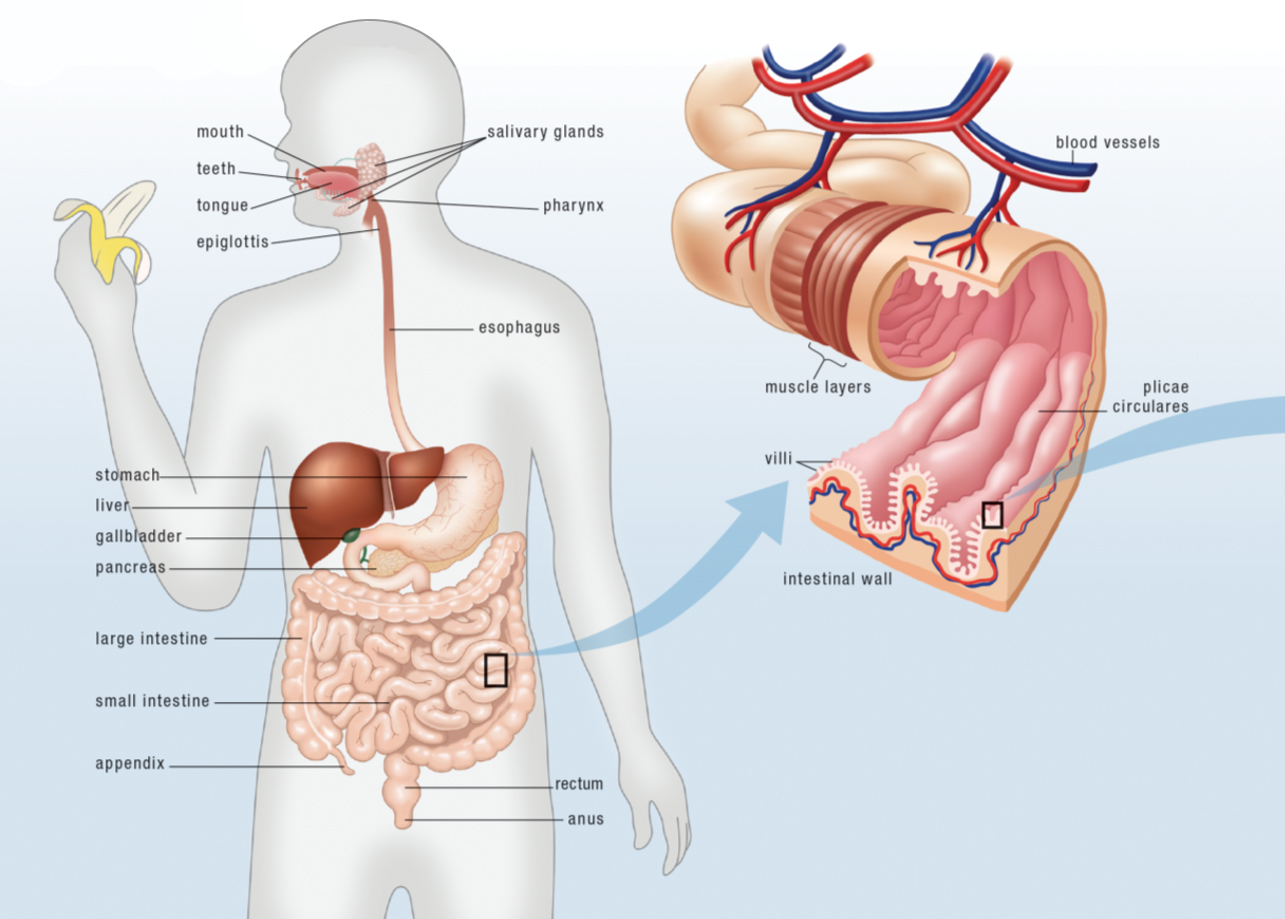

Only relatively small molecules can cross the gut barrier to enter the body, which is why digestion is a prerequisite for nutrient absorption. Nutrients are absorbed by passing through the lining of the gastrointestinal tract (via several pathways) and into the circulation (either blood or lymphatic vessels depending on whether the nutrient is water or fat soluble). Nutrients are then carried throughout the body; every part of every cell, every chemical reaction within every cell, every signaling molecule (like hormones) and even the extracellular matrix (the glue that holds our cells together) use nutrients. If nutrients are not needed immediately, they are either stored for later use, or excreted.

Supplying nutrients to our body is clearly a very important job, and without the gut to accomplish this vital function, we would be unable to survive. However, digestion is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the gut’s contribution to our health!

The Gut Barrier

The gut is essentially a really long tube, open at both ends which makes the interior of the gut an extension of the external environment. Yes, inside the gut is considered to be outside of the body since the gut’s contents can only enter the circulatory system by crossing the highly sophisticated gut barrier. In fact, the gut provides the largest amount of contact between the interior of our bodies and the outside world, far more than our skin, with an area estimated to be about the size of a tennis court!

Digestion of consumed foodstuffs into small molecules is necessary for the proper functioning of the gut barrier. The gut barrier, also called the intestinal barrier, is semipermeable. It protects our bodies by being permeable to nutrients while blocking everything else in the gut—including compounds in foods that our bodies can’t use but also toxins, pathogens and the trillions of bacteria that live in our guts—from entering the body. What we can’t absorb from our foods either becomes food for the bacteria that live in the small and large intestines or is eliminated as waste.

Digestion of consumed foodstuffs into small molecules is necessary for the proper functioning of the gut barrier. The gut barrier, also called the intestinal barrier, is semipermeable. It protects our bodies by being permeable to nutrients while blocking everything else in the gut—including compounds in foods that our bodies can’t use but also toxins, pathogens and the trillions of bacteria that live in our guts—from entering the body. What we can’t absorb from our foods either becomes food for the bacteria that live in the small and large intestines or is eliminated as waste.

Because the gut acts as the largest barrier between our bodies and the outside world, repelling foreign invaders is another key function of the gastrointestinal tract. The gut has the very tricky job of letting nutrients into the body while keeping bacteria, viruses, parasites, other pathogens and toxins from entering the body. To achieve this function, the gut is equipped with an array of physiologic defense mechanisms, including mucus, digestive enzymes, acid, and most of our immune systems! In fact, the gut houses approximately 80% of our immune systems within the largest collection of lymphoid tissue in the body, termed the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).

The first line of defense against large molecules like pathogens entering the body is digestion, with saliva, gastric acid and enzymes, and pancreatic enzymes all exerting a toxic action on microorganisms via the destruction of their cell wall. If a pathogen escapes degradation, there are two mechanisms that prevent adhesion to the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. Peristalsis, the coordinated contraction and relaxation of muscle tissues to propel the contents of the gut from one end to the other, contributes to gut barrier function by limiting the amount of time any particular pathogen might have to adhere to, colonize or cross the intestinal barrier. The entire intestinal surface is lined with a mucus layer, produced by specialized cells embedded within the intestinal wall, that acts as a physical barrier to pathogens but also contains a variety of antimicrobial compounds to destroy any infectious microbes that may enter the mucus layer. The specialized cells that form the majority of the intestinal wall, a type of epithelial cell called enterocytes that connect firmly to each other to form a continuous layer, also form a physical barrier to large amounts of pathogens. Whatever makes it through these defenses are then confronted with the immune system.

Just inside the epithelial cell layer of the intestinal wall lies a vast array of resident immune cells acting as sentries, ready to protect the body from attack. Even in normal circumstances, a constant barrage of large molecules—including partially digested food particles, pathogenic organisms, and the normal microbiotic residents of our guts—crosses into the body and must be identified and destroyed by the immune system. A variety of cell types accomplish this job, recognizing and cleaning up harmless substances, targeting harmful agents and mounting either a local or systemic immune response, and remaining constantly activated in a state of vigilance called “physiological inflammation”.

Food must be broken down into its simplest forms in order to cross the lining of the small intestine. This breaking down is achieved by the combined efforts of acid and digestive enzymes produced by the cells that line the stomach, bile salts made by the liver and stored in the gallbladder until needed, additional (and different) digestive enzymes made and secreted into the small intestine by the pancreas, and even our gut microbiota (the friendly bacteria that live in the gut). Before being absorbed into the body, proteins must be broken down into amino acids, fats must be broken down into fatty acids, and carbohydrates must be broken down into monosaccharides (simple sugars). Once food is broken down into its simplest components, the cells that line the gut transport those components from inside the gut to inside the body.

What can’t be digested by our bodies is excreted as waste (along with dead gut bacteria as their life cycles end). Amazingly, a single layer of highly specialized cells, enterocytes, is all that separates the inside of the body from the outside. These cells have two very specific jobs:

- To transport the digested nutrients from the “inside the gut” side of the cell to the “outside the gut” side of the cell

- To keep everything else inside the gut (that is, not let it enter the body)

Immediately across this barrier are two important parts of the digestive system:

- The resident immune cells of the gut, whose job is to protect us from pathogens that might find their way across the enterocyte barrier

- A network of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels that carry the digested nutrients from food to the tissues in our body that need them

Amino acids, monosaccharides, minerals and water-soluble vitamins are transported through the blood, while fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins are transported through the lymphatic system.

It’s important to understand just how essential the barrier function of the gut is to human health, because, as previously mentioned, loss of that function is a critical factor in autoimmune disease.

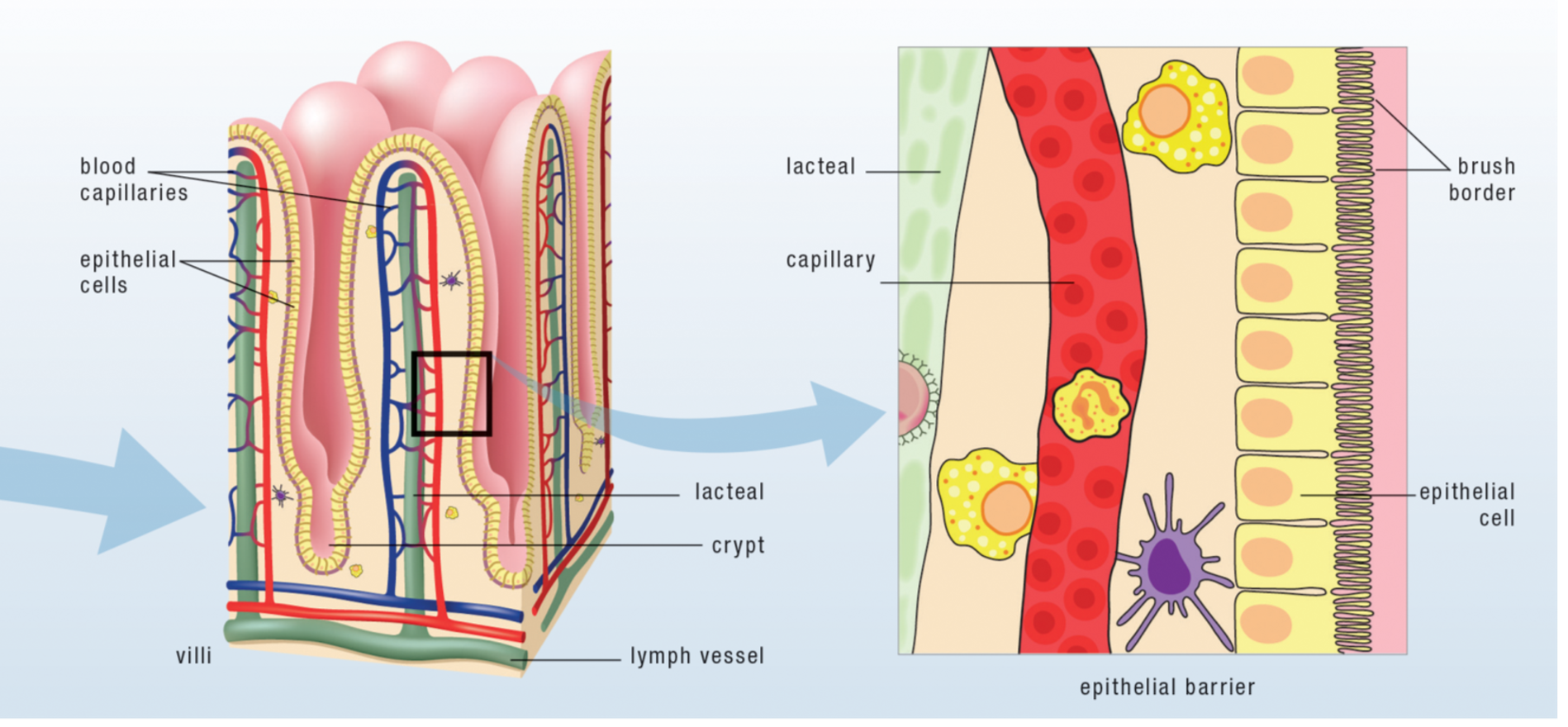

What Happens When the Gut “Leaks”?

A leaky gut occurs when either individual or groups of enterocytes are damaged or the proteins that form the tight bonds between these cells and hold them together as a solid layer are damaged. When this happens, microscopic holes are formed in the intestinal lining through which some of the contents of the gut can leak out into the bloodstream or lymphatic system—and, most important, straight into the waiting arms of the resident immune cells of the gut. What leaks out isn’t food, but a combination of pathogens: incompletely digested proteins; bacteria or bacterial fragments from those friendly bacteria that are supposed to stay in your gut; infectious organisms if they’re present in the gut; or a variety of toxic substances or waste products that would normally be excreted. When these pathogens leak through those holes, the resident immune cells of the gut recognize them as foreign invaders and mount a response against them, recruiting more immune cells from the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. When large quantities of pathogens escape, other parts of the body, especially the liver, also contribute to the response—revving up bodywide inflammation and sending the immune system into overdrive. Exactly what and how much leaks out determines the precise nature of this immune response.

Some pathogenic substances (like bacterial fragments and toxins) cause generalized inflammation by triggering the release of inflammatory cytokines (the chemical messengers that circulate in the blood and tell white blood cells to attack) that recruit the cells of the innate immune system. Recall that this type of inflammation has no specific target, so any cell in the body can be an innocent victim. These toxins must typically be filtered by the liver. When the liver is overworked, the toxins accumulate in the body and the inflammation spreads and begins to trigger the adaptive immune system to join in the battle. This type of inflammation can be a major contributor to a variety of health issues, not just autoimmune disease.

Other substances (like incompletely digested proteins or other undigested food particles) stimulate the adaptive immune system, which responds in a variety of ways, producing ailments such as allergies and autoimmune disease. An allergy results when B cells secrete IgE antibodies that target a part of a protein that is specific to the food it originated from: antibodies targeting the casein in milk causes a milk allergy, for example. A similar immune response occurs when B cells secrete IgA, IgD, IgM, or IgG antibodies. This type of immune response is technically considered a food intolerance (and not an allergy) but can cause both allergylike symptoms and symptoms you might not normally attribute to an allergy, such as pain, fatigue, and eczema. Some of the antibodies produced may also be autoantibodies, leading to the development of autoimmune disease. The release of cytokines is also stimulated, which stimulates further recruitment of cells from both the innate and the adaptive immune systems.

In some individuals, a leaky gut can develop slowly—over years or decades. Stress, sleep deprivation, and some infections may make matters worse very quickly (and unpredictably). Once you have a leaky gut, it is only a matter of time before other ailments begin to crop up. Depending on the extent of the damage to the gut lining, the exact substances that leak out, and your specific genetic makeup, the inflammation and immune reactions caused by a leaky gut can add up to any of a huge variety of health concerns, many of which can be life-threatening, including autoimmune disease.

The gut can become leaky for a variety of reasons, but they all have their root in diet and lifestyle factors (including insufficient sleep, inactivity, overtraining, and chronic stress). Other causes of a leaky gut include medications, such as corticosteroids and NSAIDs, and infections (parasites, candida, some bacteria…). In the case of short-term courses of medication or infections, what keeps the gut leaky afterward is the extra negative impact of diet and lifestyle. In the case of chronic infections, diet and lifestyle factors weaken the immune system to the point that it can’t deal with the invading microorganism. Gut flora imbalances (aka gut dysbiosis) can also directly cause a leaky gut.

Symptoms of a Leaky Gut

You may or may not know that you have a leaky gut. You may or may not have gastrointestinal symptoms. The destruction of the small intestine’s barrier causes inflammation, which may not cause overt symptoms in the earlier stages of disease. Reduction of surface area for nutrient absorption can cause micronutrient deficiencies (deficiencies in vitamins and minerals), which may manifest in a variety of ways. Damage to the enterocyte layer may result in lactose and fructose intolerance, and the inability to properly digest fats and absorb fat-soluble vitamins, but you may not attribute those to a leaky gut. In any event, if you suffer from chronic disease, the chances are extremely high that you have a leaky gut.

Sometimes the diagnosis of leaky gut syndrome is made when gastrointestinal symptoms are present with no other medical explanation. In this case, the diagnosis of leaky gut syndrome is similar to the diagnosis of irritable bowel disease… it isn’t really a condition on its own (and leaky gut syndrome has not official definition in the medical community), but rather a label for “we still need to figure out what’s going on.” See also 5 Gut Health Tests You Can Do at Home

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Bloating

- Irregular stools (constipation or diarrhea)

- Reflux/heartburn

- Burping

- Gas

- Nausea/vomiting

Skin Symptoms

- Acne

- Dry skin

- Rashes

- Hives

- Psoriasis

- Eczema

- Rosacea

- Itchy Skin

Neurological Symptoms

- Fatigue — especially after eating

- Brain fog

- Headaches (including migraines)

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Insomnia

- ADD/ADHD

Other Symptoms

- Joint pain

- General aches and pains

- Multiple food sensitivities/allergic reactions to many foods

- Autoimmune disease

- Difficulty maintaining a healthy weight

- Symptoms of malnutrition

Diseases Linked to Leaky Gut

A huge variety of health problems and chronic diseases are linked to increased intestinal permeability, including all of the following:

- multiple organ failure

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- ulcerative colitis

- Crohn’s disease

- celiac disease

- irritable bowel syndrome

- inflammatory joint disease

- ankylosing spondylitis

- psoriatic arthritis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- food allergy

- asthma

- atopic dermatitis

- eczema

- cardiovascular disease

- chronic heart failure

- stroke

- insulin resistance

- type 1 diabetes

- type 2 diabetes

- obesity

- multiple sclerosis

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- autoimmune hepatitis

- psychological conditions

- depression

- HIV/AIDS

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- chronic inflammation

There is certainly some controversy on whether leaky gut is the chicken or the egg when it comes to chronic illness, see Which comes first: the leaky gut or the dysfunctional immune system? for more information.

Mechanisms Causing a Leaky Gut

There are several ways in which the epithelial barrier can be breached and damaged. Some proteins bind to carrier molecules in the brush border of the epithelium, tricking the enterocytes into transporting them across the barrier. Some proteins irritate or damage the cells. Some affect the bonds between enterocytes.

Enterocyte Damage: Damage or destruction of the cells that line the gut occurs when certain substances interact with those cells. These substances include pathogens and toxins but also some specific dietary proteins, the most important of which are prolamins, agglutinins, and saponins, which are found in abundance in grains, legumes, and nightshade vegetables (see Why Grains Are Bad-Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?) and How Do Grains, Legumes and Dairy Cause a Leaky Gut? Part 2: Saponins and Protease Inhibitors and The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Nightshades) If an enterocyte dies, it leaves a hole in the gut barrier through which the contents of the gut can leak out. These holes are rapidly closed in a healthy individual. But when enterocyte death becomes rampant (as is the case in people with certain infections, or who are sensitive to gluten and prolamins, or who eat many prolamin-, agglutinin- and saponin-rich foods, or who have gut dysbiosis, or who have certain genetic tendencies), the body cannot keep up with the necessity for repair, and a leaky gut develops. A confounding factor for many people is a diet deficient in important nutrients required for effective repair of the gut barrier.

Tight Junctions: The cells that line the gut are bound together by structures known as tight junctions. The tight junction is a complex of many different proteins that extend from the inside of the cell through the cell membrane to the outside of the cell. These proteins fold in such a way as to weave together with proteins from the adjacent cell and form a tight connection. This tight connection is essential for the barrier junction of the intestinal epithelium. Beyond this function, the tight junctions are also responsible for dividing the cell membrane of the enterocytes into two components, the apical membrane (the “top” of the cell, or the part that faces inside the gut) and the basolateral membrane (the “sides” and “bottom” of the cell, or the part that faces inside the body). Because these parts of the cell membrane have different functions, a properly functioning tight junction is critical to a properly functioning cell. In fact, loss of what is called epithelial cell polarity (the cell’s ability to know the difference between its apical and its basolateral membranes) occurs when tight junctions are not functioning properly, and this is an essential precursor to cancer.

There are many ways the tight junctions can unravel and open up. In fact, these are not static structures, but are designed to open and close so specific nutrients can be absorbed. The problem occurs when the normally highly controlled regulation of the tight junctions fails and the tight junctions are left open. This not only creates pores through which substances inside the gut can leak out into the body, but if the situation persists it also can signal to the cell to go into apoptosis (i.e., commit cell suicide). See The WHYs behind the Autoimmune Protocol: Alcohol.

One mechanism through which tight junctions are opened is zonulin. Zonulin, a protein secreted into the gut by the enterocytes, is supposed to regulate the rapid opening and closing of tight junctions. However, it is now believed that zonulin may play a critical role in the development of autoimmune disease. Patients with celiac disease are known to have increased zonulin levels, stimulating the opening of more tight junctions and probably keeping them open for longer. In these patients, the secretion of zonulin is stimulated by the consumption of gluten (or, more specifically, the protein fraction of gluten called gliadin). Increased zonulin production, also in response to gluten, also causes a leaky gut preceding type 1 diabetes. It is believed that this mechanism may be at play in all autoimmune diseases, which also implies that gluten and similar proteins found in other grains and pseudograins (the starchy seeds of broad-leafed plants such as quinoa) may contribute to leaky gut in all people suffering from autoimmune disease.

Tight junctions are also opened by elevated cortisol levels, some medications, some infectious microorganisms, and perhaps as yet unidentified substances.

How Do You Heal A Leaky Gut?

Eliminating foods that contain compounds that can increase intestinal permeability is step 1 in healing a leaky gut, however nutrient density and lifestyle factors are also essential! Some nutrients are absolutely key for a healthy gut barrier (link zinc, which 73% of Americans don’t get enough of, see also 8 Nutrients for Leaky Gut). See What Should You Eat To Heal a Leaky Gut? and Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut.

The most thorough resource for a deep dive into repairing a leaky gut and restoring a healthy and diverse gut microbiome my Gut Health Fundamentals online course.

NEW! Gut Health Fundamentals Online Course!

- Learn how to heal your gut and support your gut microbiome

- 3 3/4 hours of video lecture + downloadable slide PDFs

- How an unhealthy gut is linked to chronic disease

- Nutrients, superfoods and supplements for gut barrier and microbiome health

- Holistic approach to gut health, including food focus, eliminations and lifestyle

Learn More or Get Instant Access

Citations

Bjarnason, I., Intestinal permeability, Gut. 1994;35(1 Suppl):S18-S22

Fasano, A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2012;42(1):71-8

Hamada, K., et al., Zonula Occludens-1 alterations and enhanced intestinal permeability in methotrexate-treated rats, Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66(6):1031-8

Heyman, M., et al., Intestinal permeability in coeliac disease: insight into mechanisms and relevance to pathogenesis, Gut. 2012;61(9):1355-64

Lambert, G.P., et al., Effect of aspirin dose on gastrointestinal permeability, Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(6):421-5

Martinez-Gonzalez, O., et al., Intestinal permeability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and their healthy relatives. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:644-648

Ménard, S., et al., Paracellular versus transcellular intestinal permeability to gliadin peptides in active celiac disease, Am J Pathol. 2012;180(2):608-15

Purohit, V., et al., Alcohol, Intestinal Bacterial Growth, Intestinal Permeability to Endotoxin, and Medical Consequences, Alcohol. 2008;42(5):349-361

Teixeira, T.F., et al., Potential mechanisms for the emerging link between obesity and increased intestinal permeability, Nutr Res. 2012;32(9):637-47

Yacyshyn, B., et al., Multiple sclerosis patients have peripheral blood CD45RO+ B cells and increased intestinal permeability. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2493-2501

Yacyshyn, B.R. and Meddings J.B., CD45RO expression on circulating CD19+ B cells in Crohn’s disease correlates with intestinal permeability. Gastroenterology. 1995;08:132-138