We are instinctively drawn to sweet foods, and as we learn how detrimental to our health sugar and sugar substitutes can be, it’s natural to seek out healthier alternatives. And while it’s easy to understand why aspartame is linked to health problems (discussed in Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners), it’s tougher to wrap our heads around the fact that sweeteners straight out of nature (like stevia leaf, see The Trouble with Stevia) are also potentially problematic. Unfortunately, you can’t cheat sweet, which I’ve covered extensively in

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- Why Is Sugar Bad?

- Is Fructose a Key Player in the Rise of Chronic Health Problems?

- Fructose and Vitamin D Deficiency: The Perfect Storm?

- Why is High Fructose Corn Syrup Bad For Us?

- Is It Paleo? Fructose and Fructose-Based Sweeteners (I’m looking at you, Agave!)

- Is It Paleo? Splenda, Erythritol, Stevia and other low-calorie sweeteners

- The Trouble with Stevia (recently updated to reflect recent research)

And while natural sugars used occasionally and moderation aren’t likely to harm us (see Natural Sugars and their Place in Paleo), many of us struggle with sugar-addiction, making even the occasional treat a slippery slope. Generally, I encourage everyone to avoid sugar and sweeteners, and allow their taste buds to adapt to the natural sweetness of fresh fruit, which is perfectly healthful to consume on a daily basis (see Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates). However, I still get asked frequently, “how about this new natural sweetener?”

A few fruit-based sweeteners have found a niche within sugar-conscious communities. They include lucuma powder, made by grinding up the dried subtropical fruit of the South American Pouteria lucuma plant, and monk fruit extract, made by dehydrating the solvent-extracted and purified juice of the fruit from the East Asian Siraitia grosvenorii plant. Are these the new superfood sweeteners that will finally allow us to enjoy a guilt-free treat, or are there problems with these options too?

Lucuma

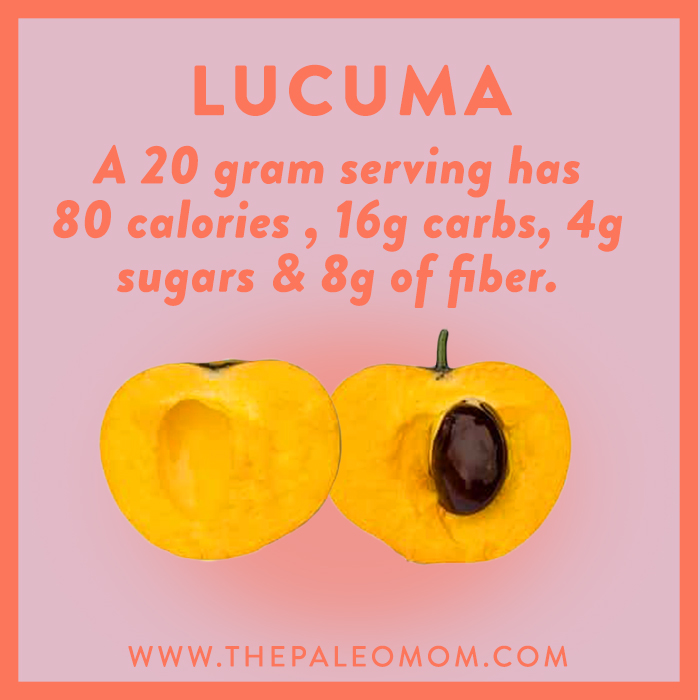

Lucuma tastes sweet owing to its sugar content, with 64% of its sugars coming from sucrose, 21% from glucose, and 15% from fructose. (A few other cultivars of lucuma have more glucose and fructose and much less sucrose.) However, the benefit of lucuma powder is that, because it’s a dehydrated whole fruit, it also contains some fiber and some more complex carbohydrates. A 20-gram serving of lucuma powder has 80 calories and contains 16 grams of carbohydrates, 4 grams of which come from sugars and 8 grams of which come from fiber. This greatly reduces its impact on blood glucose levels, although the glycemic index of lucuma powder has not yet been established. Limited nutritional information is available for lucuma, although it is rich in several important phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds and carotenoids (see The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!).

Lucuma tastes sweet owing to its sugar content, with 64% of its sugars coming from sucrose, 21% from glucose, and 15% from fructose. (A few other cultivars of lucuma have more glucose and fructose and much less sucrose.) However, the benefit of lucuma powder is that, because it’s a dehydrated whole fruit, it also contains some fiber and some more complex carbohydrates. A 20-gram serving of lucuma powder has 80 calories and contains 16 grams of carbohydrates, 4 grams of which come from sugars and 8 grams of which come from fiber. This greatly reduces its impact on blood glucose levels, although the glycemic index of lucuma powder has not yet been established. Limited nutritional information is available for lucuma, although it is rich in several important phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds and carotenoids (see The Amazing World of Plant Phytochemicals: Why a diet rich in veggies is so important!).

No toxicological studies on lucuma powder have been published in peer-reviewed journals, but given that lucuma fruit has been consumed in South America for centuries and that lucuma powder is a dehydrated whole food, it is likely a safe and nutrient-dense sugar choice (to be used in moderation along with other natural sugars, see Natural Sugars and their Place in Paleo).

Monk Fruit

Monk fruit contains sugars but also mogrosides, a glycoside that is about 300 times sweeter than sugar (glycosides are also responsible for the sweet taste of stevia, see The Trouble with Stevia). Whole monk fruit is only about 1% mogrosides, which are concentrated to 80% in monk fruit extract using solvent extraction. The flavor is rendered more neutral through the use of deodorizing agents like sulfonated polystyrene-divinylbenzene copolymer or polyacrylic acid in conventional manufacturing and charcoal or bentonite in more chemical-conscious manufacturing. Very little nutritional information on monk fruit extract is available at this time; however, given that it is a processed and refined food, little nutritional value is expected.

Monk fruit contains sugars but also mogrosides, a glycoside that is about 300 times sweeter than sugar (glycosides are also responsible for the sweet taste of stevia, see The Trouble with Stevia). Whole monk fruit is only about 1% mogrosides, which are concentrated to 80% in monk fruit extract using solvent extraction. The flavor is rendered more neutral through the use of deodorizing agents like sulfonated polystyrene-divinylbenzene copolymer or polyacrylic acid in conventional manufacturing and charcoal or bentonite in more chemical-conscious manufacturing. Very little nutritional information on monk fruit extract is available at this time; however, given that it is a processed and refined food, little nutritional value is expected.

While whole monk fruit has been consumed for centuries in Asia and is used as a cold and digestive aid in Eastern medicine, there is a scarcity of scientific studies evaluating the effects of regularly consuming high levels of mogrosides as a sugar substitute. On the pro side, mogrosides have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-cancer properties. They have no effect on the gut microbiome and lower blood glucose levels in diabetics (potentially by stimulating the release of insulin). On the con side, a thorough rat study evaluating possible toxicity of mogrosides over 4 weeks indicates some possible reasons for concern, at least for high consumption:

- Lower blood lymphocytes and (two important types of white blood cells) indicate possible immune suppression.

- Increased liver weight, decreased bilirubin and decreased prothrombin time indicate possible functional changes in the liver.

- Increased ovary and testes weights indicate a possible impact on reproductive systems.

Although no histopathological changes (changes in tissue structure that would indicate disease) accompanied the increased organ weights (adrenal gland weight also increased in male rats), increased organ weight is considered one of the most sensitive drug toxicity indicators, often preceding morphological changes to the organ (changes to the biological structure of the organs that distinctly indicate toxicity).

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Mogrosides also impact the immune system in a potentially problematic way. In mice with type I diabetes, mogrosides increased subsets of CD4+ T cells, shifting from a Th1 to a Th2 pattern via expression of the proinflammatory cytokinds IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha (see The Link Between Cancer and Autoimmune Disease). In healthy mice, mogroside increased the cytokine IL-4 which supports the development of (differentiation to) Th2 (type 2 helper) T cells. Compounds that influence Th1 vs Th2 balance are avoided on the Autoimmune Protocol due to their ability to aggravate autoimmune disease.

Clearly, more data is needed before monk fruit extract, as opposed to the whole fruit, can be endorsed as a sugar substitute.

What’s the best sugar option?

What about the next trendy superfood sweetener Contrary to all the hype you’re likely to read, there really is no way to cheat sweet. The good news is that our bodies can generally handle moderate and occasional sugar consumption, so a treat now and then isn’t out of the question (see Natural Sugars and their Place in Paleo). The best strategy is to avoid added sugars, even natural ones, on a daily basis, opting instead for whole fresh fruit (see Why Fruit is a Good Source of Carbohydrates). As your taste buds adapt to a lower sugar intake, fruit and minimally sweetened treats will taste sweeter and more indulgent.

Citations

Crellin JK & Philpott J. “A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants.” Duke University Press, 1990.

Di R, et al. “Anti-inflammatory activities of mogrosides from Momordica grosvenori in murine macrophages and a murine ear edema model.” J Agric Food Chem. 2011 Jul 13;59(13):7474-81. doi: 10.1021/jf201207m. Epub 2011 Jun 15.

Fuentealba C, et al. “Characterization of main primary and secondary metabolites and in vitro antioxidant and antihyperglycemic properties in the mesocarp of three biotypes of Pouteria lucuma.” Food Chem. 2016 Jan 1;190:403-11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.111. Epub 2015 May 28.

Livdans-Forret AB, et al. “Menorrhagia: A synopsis of management focusing on herbal and nutritional supplements, and chiropractic.” J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007 Dec; 51(4): 235–246.

Marone PA, et al. “Twenty eight-day dietary toxicity study of Luo Han fruit concentrate in Hsd:SD rats.” Food Chem Toxicol. 2008 Mar;46(3):910-9. Epub 2007 Oct 24.

Piao Y, et al. “Change Trends of Organ Weight Background Data in Sprague Dawley Rats at Different Ages.” J Toxicol Pathol. 2013 Mar; 26(1): 29–34.

Pinto MS, et al. “Evaluation of antihyperglycemia and antihypertension potential of native Peruvian fruits using in vitro models.” J Med Food. 2009 Apr;12(2):278-91. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0113.

Qi XY, et al. “Mogrosides extract from Siraitia grosvenori scavenges free radicals in vitro and lowers oxidative stress, serum glucose, and lipid levels in alloxan-induced diabetic mice.” Nutr Res. 2008 Apr;28(4):278-84. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.02.008.

Secretaria, et al. “Comparison of the Elemental Content of 3 Sources of Edible Sugar.” The Philippine Food and Nutrition Research Institute. Analyzed by PCA-TAL, Sept. 11, 2000. 2003. In parts per million (ppm or mg/li).

Xiangyang Q, et al. Effect of a Siraitia grosvenori extract containing mogrosides on the cellular immune system of type 1 diabetes mellitus mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006 Aug;50(8):732-8.

Zhou Y, et al. Insulin secretion stimulating effects of mogroside V and fruit extract of luo han kuo (Siraitia grosvenori Swingle) fruit extract. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2009 Nov;44(11):1252-7.