The idea that grains are harmful is one of the most fundamental tenets of the Paleo diet. But, the rationale for avoiding them is often misunderstood, and sometimes oversimplified to the idea that early humans didn’t have access to significant quantities of grains, and therefore, we shouldn’t eat them either (an argument that’s hardly scientific and extremely easy to refute!).

Actually, a large body of literature (as well as basic physiology and biochemistry) sheds light on how grains can harm us, and why replacing them with nutrient-dense Paleo foods can be a boon for our health. Here’s what we need to know!

Grains have a particularly high concentration of two types of lectin. Lectins are a class of proteins that are present in all plant life to some degree (the gluten in wheat is a famous example). Two sub-classes of lectins, prolamins (like gluten) and agglutinins (like wheat germ agglutinin) are of particular concern for human health (see also Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?)). These “toxic” lectins are part of a plant’s natural defense system against predators and pests, and are usually concentrated in the seeds of the plant (which is why grains and legumes have so much). To defend itself, the seed from these plants either deter predators (like us) from eating them by making us sick or resist digestion completely or both.

The grains and legumes that have become a part of the human diet since the Agricultural Revolution 10,000 years ago aren’t toxic enough to make most of us severely ill immediately after eating them (otherwise humans never would have domesticated them!). Instead, their effects are more subtle and can take years to manifest as a life-threatening disease.

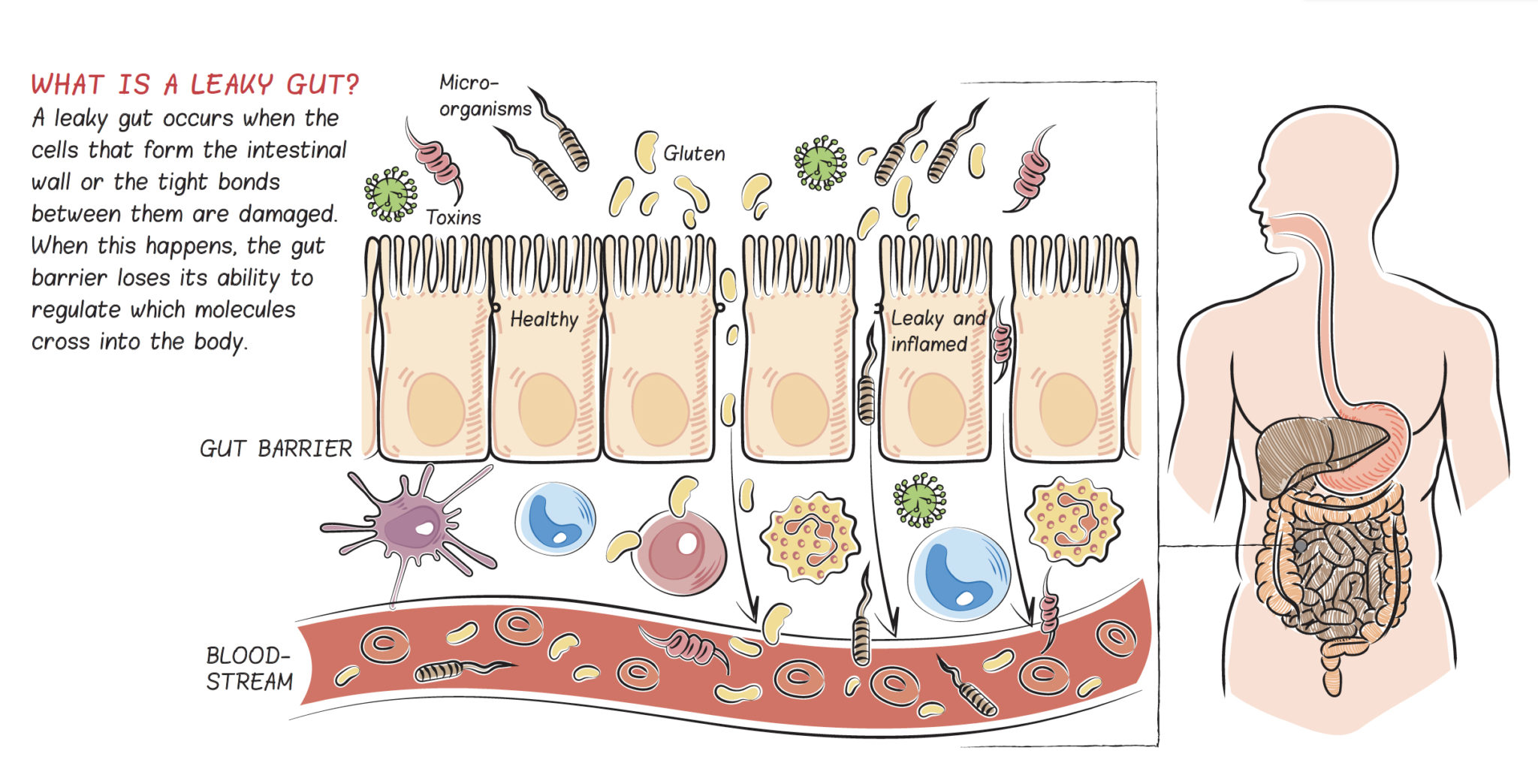

So, what happens when we eat consume these prolamins and agglutinins? Similar to what occurs in individuals with celiac disease (basically, a super exaggerated form of the sensitivity we all have to gluten and other lectins), these particular lectins can either damage and kill the cells that line our intestines, or directly cause spaces to open up between our gut cells. Yikes!

First, these types of lectins are not broken down in the normal digestive process, both because the structure of these proteins are not compatible with our bodies’ digestive enzymes and also because the foods that contain these particular lectins also contain protease inhibitors (compounds that stop the enzymes from breaking down proteins). These lectins can trick the enterocytes (the cells that line the gut) into thinking they are simple sugars. The enterocytes “willingly” transport the lectins from the “inside-the-gut” side of the cell to the “outside-the-gut” side of the cell. While in transit, the “toxic” lectins may cause changes inside the enterocyte that either kill the cell or render it ineffective at its job, which leads to more pathogens leaking out of the gut.

Once outside the gut, prolamins and agglutinins activate the resident immune cells of the gut, which respond by producing inflammatory cytokines (the chemical messengers that circulate in the blood and tell white blood cells to attack) as well as antibodies against these foreign proteins. Because at least part of this response is not specific to the lectin itself, the enterocytes (being the closest innocent bystanders) can be targeted and killed by the body’s immune cells, leading to the microscopic holes that create a leaky gut.

The result is what essentially amounts to tiny holes in our intestines, allowing the entrance of things that are not supposed to get into our blood stream. This “leak” is made worse by the fact that lectins bind to sugars and other molecules in the gut, in turn “helping” these random other molecules leak into the blood stream. There are many things in our guts (like the bacteria E. coli) that are supposed to stay there; and, when they enter into the blood stream, they cause a low level of systemic inflammation. This can set the stage for many health conditions, including cardiovascular and autoimmune diseases.

A huge number of prolamins and agglutinins exist in food, and some are more harmful than others. Gluten is by far the most damaging. In many individuals (like those with diagnosed gluten sensitivity and celiac disease), gluten can weaken the connections between enterocytes, essentially creating a space in between the cells through which gut contents can escape, adding yet another way that this particular lectin can cause a leaky gut. Once gluten has passed through the gut lining, it stimulates the resident immune cells of the gut to start producing antibodies. Gluten is especially insidious because parts of this protein closely resemble many proteins in the human body, so there’s a high likelihood that some of the antibodies produced to target it will also target human cells!

One commonly formed antibody triggered by gluten exposure is against the enzyme, transglutaminase. Transglutaminase is an essential enzyme in every cell of the body. It makes important modifications to proteins as they are produced inside the cell, and also stimulates wound healing. But, the playing field changes if antibodies have formed against it! When damaged cells secrete transglutaminase in inflamed areas of the small intestine (or any other damaged tissue in the body), rather than helping to heal the surrounding tissue, it instead turns the area into a target for the immune system. This is yet another mechanism linking gluten with a leaky gut. Importantly, when antibodies against transglutaminase form, every cell and organ in the body becomes a potential target. Because an exaggerated sensitivity to gluten is the cause of celiac disease, which affects at least 1 in 133 people, its effects on the gut have been the most studied. Scientists still don’t know which of the many ways that gluten can harm the body apply to all lectins and which are specific to gluten.

But, non-gluten lectins can be harmful as well. Wheat germ agglutinin may actually have a larger negative impact on our health (it has the added effect of stimulating inflammation), which is why the simple act of removing wheat from our diets can make such a profound difference. And, while some of the other “blacklisted” foods are okay for occasional consumption (like dairy, beans, and rice), I suggest a lifelong dedication to gluten and wheat avoidance. It can take up to six months for our guts to fully heal after a single gluten exposure (see How Long Does it Take the Gut to Repair after Gluten Exposure?)!

Beyond the fact that some lectins are more problematic than others, dose is another important factor here. The vegetables and fruits that our prehistoric ancestors ate in large quantities are generally very low in lectins, and come with a friendlier defense strategy: we get to eat the delicious fruit encasing the seeds and then the seeds, which pass through our digestive tracts intact, get to be planted in rich manure. (That’s much different than the case with grains, whose lives depend on not getting eaten and crushed with our teeth!) And, the lectins fruits and vegetables do contain generally interact much less strongly with the gut barrier than the lectins found in grains. Grains (especially wheat) and legumes (especially soy and peanuts) are very high in prolamins and agglutinins, the two sub-classes of lectins with the greatest negative impact on the barrier function of the gut. (That’s where the gut is supposed to selectively allow digested nutrients from our foods into our body and keep out everything else.) And, if damaging the gut lining and causing systemic inflammation isn’t enough, lectins are also anti-nutrients, which means they stop us from absorbing many of the vitamins and minerals in our food (like calcium!). Given that they’re also a nutrient-poor food choice (see Gluten-Free Diets Can Be Healthy for Kids and Why Grains Are Bad: Part 3, Nutrient Density and Acidity), the cons list is really stacking up!

With all that in mind, it’s easy to see why grains aren’t a good food to include in our diet (much less eat as a staple!). But, the problems with grains don’t end with lectins. In the next installments of this series Why Grains Are Bad–Part 2, Omega 3 vs. 6 Fats, and Why Grains Are Bad: Part 3, Nutrient Density and Acidity, we’ll learn more about how grains can harm our health at a biochemical level!

Citations

Agardh D, et al. “Reduction of tissue transglutaminase autoantibody levels by gluten-free diet is associated with changes in subsets of peripheral blood lymphocytes in children with newly diagnosed coeliac disease.” Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144(1):67-75.

Alaedini A & Latov N. “Transglutaminase-independent binding of gliadin to intestinal brush border membrane and GM1 ganglioside.” J Neuroimmunol. 2006;177(1-2):167-72.

Antvorskov JC, et al. “Dietary gluten alters the balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in T cells of BALB/c mice.” Immunology. 2013;138(1)23-33.

Antvorskov JC, et al. “Impact of dietary gluten on regulatory T cells and Th17 cells in BALB/c mice.” PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33315.

Calder PC. “Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology?” Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Mar;75(3):645-62.

Dawson-Hughes B, et al. “Alkaline diets favor lean tissue mass in older adults.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Mar;87(3):662-5.

De Punder K & Pruimboom L. “The Dietary Intake of Wheat and other Cereal Grains and Their Role in Inflammation.” Nutrients. 2013;5(3):771-787.

Scialla JJ & Anderson C. “Dietary acid load: A novel nutritional target in chronic kidney disease?” Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013 Mar;20(2):141-149.

Simopoulos AP. “The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids.” Biomed Pharmacother. 2002 Oct;56(8):365-79.

Vasconcelos IM & Oliveira JT. “Antinutritional properties of plant lectins.” Toxicon. 2004 Sep 15;44(4):385-403.