SCIENCE SIMPLIFIED:

- Exercise is essential for regulated hormones, a healthy immune system, a healthy gut microbiome, and central nervous system health. That’s how it can benefit risk of so many chronic diseases!

- For diverse health benefits, aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderately-intense physical activity, meaning you can hold a conversation (if barely) while exercising. For even greater effect, aim for at least 300 minutes per week!

- It’s also important to avoid being sedentary, so take a 2-minute movement break every 20 minutes of sedentary (sitting) time.

- Use the Perceived Exertion Scale to dial in intensity. Too-intense exercise for prolonged periods can contribute to leaky gut.

RELATED READING:

- The Benefits of Gentle Movement

- 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food

- Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

The importance of exercise is ingrained in our minds, and for good reason: studies routinely show that physical activity is health-protective, and we’ve identified a wide range of mechanisms explaining why that’s the case. Getting regular moderate exercise decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, depression, and some cancers. In fact, the World Health Organization has identified a lack of physical activity as the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, being responsible for an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally each year! With such strong science supporting its role in our lives, physical activity is a clear tenet of the Paleo framework. Let’s review the diverse benefits of exercise.

Save 80% Off the Foundations of Health

Expand your health knowledge on a wide range of topics relevant to you, from how to evaluate scientific studies, to therapeutic diet and lifestyle, to leaky gut and gut microbiome health, to sustainable weight loss, and much more!!!

First, let’s get one thing straight: exercise is not just about “burning calories.” The number of calories we burn when exercising compared to sitting and doing nothing is not really that significant. It certainly adds up slowly considering that 3,500 calories is equivalent to 1 pound of stored energy. If we want to lose weight, we should focus on dietary changes (see Paleo for Weight Loss). But exercise still plays an important role in health management. Instead of a calorie burner, we should think of exercise as a hormone manager.

Hormones are chemical messengers in contact with virtually every cell in the body, and they are sensitive to the demands of cells. When hormones sense changes in body chemistry, they respond rapidly to ensure that the cells get everything they need to stay healthy. Exercise has a profound effect on every hormone system in the body. Whether the exercise is aerobic or anaerobic, cardio intensive or strength training focused, low intensity or high intensity, and short duration or long duration, virtually every hormone system benefits. It also matters what time of day we exercise, whether we exercise in a fasted state, and what other stressors are present (mental stress, lack of sleep, poor-quality diet, and so on). However, what is uniformly true is that exercise improves hormone regulation.

Some of the advantages of exercise are obvious. Increasing muscle mass causes an increase in metabolism, making it easier to maintain a healthy weight. Of course, most people like the way they look when they have bigger, more defined muscles, boosting self esteem. In fact, there are no negative aspects to being stronger, faster, more flexible, and more agile.

Benefits of Exercise

As you contemplate adding more or different types of activity to your life, there are some additional benefits of exercise that you might not immediately consider. For example:

Appetite and weight control. Exercise is known to regulate key hunger hormones such as leptin and ghrelin and may promote healthier digestion through hormone regulation (see The Hormones of Hunger and The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin). It is not necessarily true that exercise makes us hungrier, although it may seem that way. In fact, for many people (and depending on the type of exercise), exercise makes it easier to consume fewer calories in an entire day, even if they eat a bigger meal right after working out—and as an added perk, exercise leads many people to crave healthier, more nutrient-dense foods. Exercise can also help control the intensity of unhealthy food cravings, translating to increased willpower. Exercise is also believed to help lower our body weight “set point,” based on the controversial idea that there is a set weight at which the body “wants” to be, which is determined by hormones, which are, in turn, influenced by diet and lifestyle. See also Paleo for Weight Loss

Appetite and weight control. Exercise is known to regulate key hunger hormones such as leptin and ghrelin and may promote healthier digestion through hormone regulation (see The Hormones of Hunger and The Hormones of Fat: Leptin and Insulin). It is not necessarily true that exercise makes us hungrier, although it may seem that way. In fact, for many people (and depending on the type of exercise), exercise makes it easier to consume fewer calories in an entire day, even if they eat a bigger meal right after working out—and as an added perk, exercise leads many people to crave healthier, more nutrient-dense foods. Exercise can also help control the intensity of unhealthy food cravings, translating to increased willpower. Exercise is also believed to help lower our body weight “set point,” based on the controversial idea that there is a set weight at which the body “wants” to be, which is determined by hormones, which are, in turn, influenced by diet and lifestyle. See also Paleo for Weight Loss

- Metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Exercise helps improve insulin sensitivity (and therefore blood sugar regulation) through direct action on the glucose transport molecules in the individual cells of our muscles. It also affects the full range of hormones related to accessing stored energy and regulating how that energy is used. This “boost” in metabolism is one reason why exercising can make us feel more energetic throughout the day(and who doesn’t love having high energy levels!). It is also a major reason why exercise is linked with a reduced risk of diabetes and heart disease. See 3 Ways to Regulate Insulin that Have Nothing to Do With Food and The Paleo Diet for Diabetes

- Body composition and bone health. When we exercise, our muscles get stronger (and

sometimes bigger, depending on the type of exercise). This muscle gain is one contributor to increased metabolism (basal metabolic rate). As an important part of long-term health, exercise—especially weight-bearing exercise—stimulates our bodies to make stronger and denser bones. Exercise (or lack thereof) is a bigger determinant of loss of bone density (osteopenia and osteoporosis risk) than diet!

sometimes bigger, depending on the type of exercise). This muscle gain is one contributor to increased metabolism (basal metabolic rate). As an important part of long-term health, exercise—especially weight-bearing exercise—stimulates our bodies to make stronger and denser bones. Exercise (or lack thereof) is a bigger determinant of loss of bone density (osteopenia and osteoporosis risk) than diet!  Stress management. Exercise is very effective at modulating levels of the stress hormone cortisol. This is a bit of a double-edged sword because exercising too intensely can raise cortisol levels too high and lead to adrenal fatigue (see How Stress Undermines Health, Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What Is Adrenal Fatigue?, Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 2: Testing Adrenal Glandular Function and Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 3: Nutrition; Lifestyle Support for the Adrenal Glands). However, if we keep exercise to an appropriate duration and intensity for our particular fitness level (and for how well we eat, sleep, and manage stress), exercise becomes potent at reducing and normalizing cortisol levels, which can also help reduce inflammation and promote healing. This makes it easier to burn stored energy (especially fat), in addition to improving sleep and making us feel more relaxed and able to cope with life’s surprises.

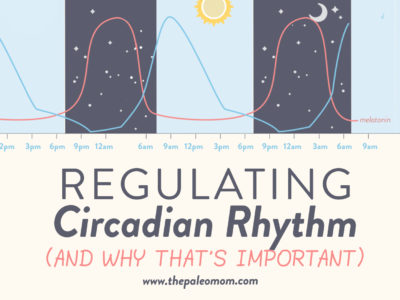

Stress management. Exercise is very effective at modulating levels of the stress hormone cortisol. This is a bit of a double-edged sword because exercising too intensely can raise cortisol levels too high and lead to adrenal fatigue (see How Stress Undermines Health, Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 1: What Is Adrenal Fatigue?, Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 2: Testing Adrenal Glandular Function and Demystifying Adrenal Fatigue, Pt. 3: Nutrition; Lifestyle Support for the Adrenal Glands). However, if we keep exercise to an appropriate duration and intensity for our particular fitness level (and for how well we eat, sleep, and manage stress), exercise becomes potent at reducing and normalizing cortisol levels, which can also help reduce inflammation and promote healing. This makes it easier to burn stored energy (especially fat), in addition to improving sleep and making us feel more relaxed and able to cope with life’s surprises. Sleep quality. Beyond its effect on cortisol, exercise regulates several key hormones related to circadian rhythm. Therefore, when we exercise during the day, we’ll fall asleep easier, sleep more soundly, and experience more restorative sleep so that we wake up feeling more refreshed (provided that we allotted adequate time for sleep). As discussed in Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!, sleeping better positively affects just about everything in our bodies, from cortisol levels to the ability to resolve inflammation (see also Sleep Requirements and Debt: How do you know how much sleep you need? and 10 Tips to Improve Sleep Quality). But be aware that exercising too intensely late in the evening can make it more difficult to fall asleep.

Sleep quality. Beyond its effect on cortisol, exercise regulates several key hormones related to circadian rhythm. Therefore, when we exercise during the day, we’ll fall asleep easier, sleep more soundly, and experience more restorative sleep so that we wake up feeling more refreshed (provided that we allotted adequate time for sleep). As discussed in Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!, sleeping better positively affects just about everything in our bodies, from cortisol levels to the ability to resolve inflammation (see also Sleep Requirements and Debt: How do you know how much sleep you need? and 10 Tips to Improve Sleep Quality). But be aware that exercising too intensely late in the evening can make it more difficult to fall asleep. Mood. Beyond its effect on cortisol, exercise releases endorphins, which have a direct reflection on several key neurotransmitters that are related to mood. Making time to exercise can help fight depression and anxiety and improve your general outlook on life. Exercising also increases blood flow to the brain and in turn helps reduce inflammation in the brain (which is how exercise boosts mood but is also likely why exercise can help improve some cognitive performance markers in people with Alzheimer’s disease). This is an important strategy for people with gut-brain axis problems (impaired signals between the brain and the digestive system; see How Stress Undermines Health, How Chronic Stress Leads to Hormone Imbalance, and Paleo for Mental Health).

Mood. Beyond its effect on cortisol, exercise releases endorphins, which have a direct reflection on several key neurotransmitters that are related to mood. Making time to exercise can help fight depression and anxiety and improve your general outlook on life. Exercising also increases blood flow to the brain and in turn helps reduce inflammation in the brain (which is how exercise boosts mood but is also likely why exercise can help improve some cognitive performance markers in people with Alzheimer’s disease). This is an important strategy for people with gut-brain axis problems (impaired signals between the brain and the digestive system; see How Stress Undermines Health, How Chronic Stress Leads to Hormone Imbalance, and Paleo for Mental Health). Gut health. While strenuous, exhaustive exercise is detrimental to gut health (see Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut and What Is A Leaky Gut? (And How Can It Cause So Many Health Issues?)), moderate-intensity exercise is a boon to the community of microorganisms in our gut. While more research is still needed, there is compelling evidence that regular physical activity by itself increases gut microbial diversity and supports the growth of important probiotic strains like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus (see The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods). While most of the research to date has been performed in rodents, one human study comparing the gut microbiota of rugby players to those of healthy controls showed nearly double the number of microbial strains in the athletes.

Gut health. While strenuous, exhaustive exercise is detrimental to gut health (see Why Exercising Too Much Hurts Your Gut and What Is A Leaky Gut? (And How Can It Cause So Many Health Issues?)), moderate-intensity exercise is a boon to the community of microorganisms in our gut. While more research is still needed, there is compelling evidence that regular physical activity by itself increases gut microbial diversity and supports the growth of important probiotic strains like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus (see The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods). While most of the research to date has been performed in rodents, one human study comparing the gut microbiota of rugby players to those of healthy controls showed nearly double the number of microbial strains in the athletes.

How do you determine which exercise is best for you? There are different benefits of exercise, depending on the type, duration, and intensity, but with the exception of over-training (exercising too intensely or for too long of a duration for your individual fitness level), all exercise is extremely beneficial. What activity is best for you depends on your goals and current health status. What matters most is that you do something—even if it’s just a leisurely stroll. Even better, do something you really enjoy. If you enjoy the activity, you’re far more likely to keep doing it!

Regular exercise doesn’t have to mean pouring sweat and exhausting yourself at the gym for 2 hours every day. Simply going for a 30-minute walk most days, while also taking short movement breaks throughout the day, yields almost all the benefits of physical activity! See also The Benefits of Gentle Movement.

Living an Active Lifestyle

Ultimately, what all this means is that it’s more important to be active than it is to exercise in ways that are too strenuous or acute. The best scenario for our health is to do light to moderate activity for as much of the day as possible. This includes gentle activities like going for walks, taking the stairs, parking in the farthest space instead of the closest, working at a treadmill desk, gardening, doing housework, playing actively with the kids or the dog, and maybe getting some moderately intense activity designed to build strength, like lifting weights or doing yoga. The key is to avoid being sedentary, especially sitting for prolonged periods, and to avoid doing overly strenuous or prolonged physical activities like endurance training and HIIT (high-intensity interval training) workouts.

Ultimately, what all this means is that it’s more important to be active than it is to exercise in ways that are too strenuous or acute. The best scenario for our health is to do light to moderate activity for as much of the day as possible. This includes gentle activities like going for walks, taking the stairs, parking in the farthest space instead of the closest, working at a treadmill desk, gardening, doing housework, playing actively with the kids or the dog, and maybe getting some moderately intense activity designed to build strength, like lifting weights or doing yoga. The key is to avoid being sedentary, especially sitting for prolonged periods, and to avoid doing overly strenuous or prolonged physical activities like endurance training and HIIT (high-intensity interval training) workouts.

It’s important to understand that the meaning of “too strenuous” is different for different people. Clearly, how physically fit you are will determine what workout intensity is going to mean overdoing it. As previously discussed, other important lifestyle factors play into this as well: how long we give ourselves to recover after an intense workout (at least 24 hours, and preferably 48), how well we manage stress, whether we work out in the heat (which can increase leaky gut), and whether we’re getting adequate sleep. The micronutrient density of our diet is almost certainly a player as well; our diet affects the health of our adrenal glands, neurotransmitter regulation, and the gut microbiome.

So what’s the takeaway? There’s no benefit to overexerting ourselves in the gym or on the pavement. Where to draw the “overexertion” line is an individual choice, and we have to listen to our bodies and experiment. While science can point us in the right direction, the details are up to each of us to dial in.

All that said, there are a few important things to keep in mind when implementing the “activity” tenet of Paleo:

- Don’t overdo it. Pushing our bodies too hard can cause an increase in stress hormone production, harm gut health, compromise our immune systems, and lead to other problems. It’s better to go for a long, slow stroll than to sprint for 20 minutes and induce feelings of imminent death. We can push our bodies to do more, but we should aim for gradual improvement.

- Diversify for more benefits. Find an activity that builds strength and an activity that provides some cardiovascular conditioning. Better yet, try something that does both. But remember that neither strength-building nor cardio activities should be strenuous.

- Protect your joints, back, and brain. Whatever activities you do, be aware of the injury risks involved and take precautions to protect your body. This means taking time for proper warm-ups and cool-downs, stretching, and practicing correct technique in addition to wearing the right gear and following safety protocols.

- Think about the long term. Find activities that you can do for the rest of life, even if the intensity decreases over time. If you can create a social aspect to your activities, all the better.

- Do it for enjoyment. If you love doing a physical activity, chances are you’ll want to do it more to the point that it becomes more like a hobby than a chore. If you stop enjoying the activity, it’s time to take a break and find something else to do. Having fun is key!

Movement and Activity Guidelines

The bottom line is that the more active we are, the healthier we can be, reducing risk of nearly every chronic disease, improving a variety of health conditions once diagnosed, and improving quality of life into our old age. So how much activity is enough to reap all of the benefits of regular exercise? The following guidelines taken from American Heart Association and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and updated to reflect current research. Scroll down for an infographic.

Avoid Being Sedentary

- Take a 2-minute movement break after every 20 minutes of sedentary (sitting) time.

- During your 2-minute breaks, walk around or move in some other way; research shows that it isn’t enough to simply stand up.

Weekly Activity Targets

- Studies show major health benefits with at least 150 minutes (2½ hours) of moderately intense activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity each week.

- Recent studies show that it doesn’t make a difference whether you get your 150 minutes of moderate activity in one 2½-hour session once per week or five 30-minute sessions spread throughout the week.

- The more active you are, the greater the health benefits, provided that you are giving your body sufficient recovery time between vigorous workouts.

- For even greater health benefits, aim for 300 minutes (5 hours) of moderately intense activity or 150 minutes (2½ hours) of vigorous activity each week.

- You can absolutely mix it up with some moderate activity and some vigorous activity. As a general rule, 1 minute of vigorous activity is equivalent (in terms of health benefits) to about 2 minutes of moderate activity.

Muscle-Strengthening Activities

- Muscle-strengthening activities should be included two or more days a week.

- These activities should work all the major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, chest, abdomen, shoulders, and arms) within the week.

Aerobic Activity

- Engage in aerobic exercise (that is, elevate your heart and respiration rates due to exertion) for at least 10 minutes at a time.

- Spread aerobic activity throughout the week.

Make Gradual Changes

- Especially if you’re starting out as an inactive person, add minutes of physical activity and increase the intensity of physical activity gradually.

- Set both short term and long term goals for activity.

- Some physical activity is better than none.

- You can gain health benefits from as little as 1 hour of moderately intense activity per week, so that’s a great beginner’s goal.

Rest and Recovery

- Make sure you are getting ample recovery time between training sessions (at least 24 hours).

- Get enough sleep every night (see Sleep and Disease Risk: Scarier than Zombies!).

- Be sure to eat enough food to support recovery and repair between training sessions.

- During intense exercise, consume approximately 16 ounces per hour of a beverage that contains less than 10 percent carbohydrates but includes glucose, fructose, and electrolytes.

- Stretch before and after vigorous activity and any activity that might strain muscles. Self-myofascial massage (“rolling out” the muscles) is also very beneficial.

- Listen to your body and reduce the intensity of your workouts if you have very sore muscles, feel fatigued or sluggish, or feel like you may be getting sick.

Dialing in Intensity

- The intensity of your activity is relative to your individual capacity. What is vigorous for one person might be moderate for another or impossible for someone else.

- Target heart rate is one way to dial in intensity, but the RPE scale is just as good and doesn’t require fancy heart rate monitors!

- During your workouts, use the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale to assign numbers to how you feel. Rate your perceived exertion on a scale from 0 to 20, with 0 being lying in bed and 20 being sprinting as fast as you can. Moderately intense activity usually corresponds to an RPE of 11 to 14. Vigorous activity usually corresponds to an RPE of 17 to 19.

| 1–6 | No exertion at all |

| 7–8 | Extremely light |

| 9–10 | Very light |

| 11–12 | Light |

| 13–14 | Somewhat hard |

| 15–16 | Hard (heavy) |

| 17–20 | Very hard |

- You can also use the “talk test” to estimate the intensity of your workout. Most people are able to talk or hold a conversation during moderately intense activity. During vigorous activity, holding a conversation or saying more than a few words before running out of breath is challenging.

Examples of moderate intensity: Walking briskly (generally 3 or more miles per hour, but not race-walking), water aerobics, bicycling slower than 10 miles per hour, tennis (doubles), ballroom dancing, general gardening

Examples of vigorous intensity: CrossFit, HIIT (high-intensity interval training) such as many boot-camp programs, race-walking, jogging or running, swimming laps, tennis (singles), aerobic dancing, bicycling 10 miles per hour or faster, jumping rope, heavy gardening (continuous digging or hoeing), hiking uphill or with a heavy backpack

Examples of muscle-strengthening activities: CrossFit, lifting weights, working with resistance bands, other forms of resistance training, bodyweight movements such as sit-ups and push-ups, yoga, heavy gardening

Citations

Akama T, et al. [“Change of salivary secretory IgA by 42 months exercise training in elderly persons”]. Sport Science Research. 2: 122-127, 2005.

Alley JR, Mazzochi JW, Smith CJ, Morris DM, Collier SR. Effects of resistance exercise timing on sleep architecture and nocturnal blood pressure. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(5):1378-85.

Bailey DP and Locke CD. “Breaking up prolonged sitting with light-intensity walking improves postprandial glycemia, but breaking up sitting with standing does not.” J Sci Med Sport. 2015 May;18(3):294-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.03.008. Epub 2014 Mar 20.

Bey and Hamilton. “Suppression of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity during physical inactivity: a molecular reason to maintain daily low-intensity activity.” J Physiol. 2003 Sep 1;551(Pt 2):673-82. Epub 2003 Jun 18.

Biswas, et al. “Sedentary Time and Its Association With Risk for Disease Incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):123-132.

Bollinger, T., et al., Sleep-dependent activity of T cells and regulatory T cells, Clin Exp Immunol. 2009 Feb;155(2):231-8

Bosy-Westphal, A., et al., Influence of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance and insulin sensitivity in healthy women, Obes Facts. 2008;1(5):266-73

Boudjeltia KZ, et al., Sleep restriction increases white blood cells, mainly neutrophil count, in young healthy men: a pilot study, Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(6):1467-70.

Chennaoui M, Arnal PJ, Sauvet F, Léger D. Sleep and exercise: a reciprocal issue?. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;20:59-72.

Cohen, S et a., Psychological Stress and Disease, JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1685.

Cohen, S., et al., Chronic stress, glucocorticoid recep¬tor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):5995-9

Dhabhar, F. S. and McEwen, B. S., Acute stress en¬hances while chronic stress suppresses immune function in vivo: a potential role for leukocyte trafficking, Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11:286-306

Donga, E., et al., A single night of partial sleep deprivation induces insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways in healthy subjects, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;95(6):2963-8.

Dunstan DW, et al. “Television Viewing Time and Mortality: The Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab).” Circulation. 2010; 121: 384-391.

Dunstan DW, et al. “Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting Reduces Postprandial Glucose and Insulin Responses” Diabetes Care. 2012 May; 35(5): 976–983.

Dzierzewski JM, Buman MP, Giacobbi PR, et al. Exercise and sleep in community-dwelling older adults: evidence for a reciprocal relationship. J Sleep Res. 2014;23(1):61-8.

Eda N, et al. “Effects of yoga exercise on salivary beta-defensin 2.” Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013 Oct;113(10):2621-7. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2703-y. Epub 2013 Aug 8.

Frey, D.J., et al., The effects of 40 hours of total sleep deprivation on inflammatory markers in healthy young adults, Brain Behav Immun. 2007 Nov;21(8):1050-7

Fullagar HH, Skorski S, Duffield R, Hammes D, Coutts AJ, Meyer T. Sleep and athletic performance: the effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports Med. 2015;45(2):161-86.

Gurven M, et al. “Physical Activity and Modernization among Bolivian Amerindians.” PLoS One. January 31, 2013.

Hamilton MT, et a. “Exercise physiology versus inactivity physiology: an essential concept for understanding lipoprotein lipase regulation.” Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004 Oct;32(4):161-6.

Hamilton MT, et al. “Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.” Diabetes. 2007 Nov;56(11):2655-67. Epub 2007 Sep 7.

Havas, et al. “Lymph flow dynamics in exercising human skeletal muscle as detected by scintography.” J Physiol. 1997 Oct 1;504 ( Pt 1):233-9.

Healy GN, et al. “Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk.” Diabetes Care. 2008 Apr;31(4):661-6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. Epub 2008 Feb 5.

Heslop, P., et al., Sleep duration and mortality: The effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in working men and women, Sleep Med. 2002 Jul;3(4):305-14.

Hirotsu, C., et al., Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis, PLoS One. 2012;7(11)

Kerjaschki D. “The lymphatic vasculature revisited.” J Clin Invest. 2014 Mar 3; 124(3): 874–877.

Kim KZ, et al. “The beneficial effect of leisure-time physical activity on bone mineral density in pre- and postmenopausal women.” Calcif Tissue Int. 2012 Sep;91(3):178-85. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9624-3. Epub 2012 Jul 6.

Koster A, et al. “Association of sedentary time with mortality independent of moderate to vigorous physical activity.”PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037696. Epub 2012 Jun 13.

Langsetmo L, et al. “Physical activity, body mass index and bone mineral density—associations in a prospective population-based cohort of women and men: The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos).” Bone. 2012 Jan;50(1):401-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.11.009. Epub 2011 Nov 30.

Larsen RN, et al. “Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces resting blood pressure in overweight/obese adults.” Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014 Sep;24(9):976-82. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.04.011. Epub 2014 May 2.

Lehrer S, et al., Insufficient sleep associated with increased breast cancer mortality, Sleep Med. 2013 Mar 4 pii: S1389-9457(12)00384-X. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.012. [Epub ahead of print]

Lucassen EA, et al., Interacting epidemics? Sleep curtailment, insulin resistance, and obesity, Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012 Aug;1264(1):110-34

Meier-Ewert HK, et al., Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk, J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Feb 18;43(4):678-83.

Miyachi M, et al. “Installation of a stationary high desk in the workplace: effect of a 6-week intervention on physical activity.” BMC Public Health. 2015 Apr 12;15:368. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1724-3.

O’Donovan G, et al. “Association of “Weekend Warrior” and Other Leisure Time Physical Activity Patterns With Risks for All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality.” JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Mar 1;177(3):335-342. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014.

O’Keefe, et al. “Organic fitness: physical activity consistent with our hunter-gatherer heritage.” Phys Sportsmed. 2010 Dec;38(4):11-8. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.12.1820.

Oppezzo and Schwartz. “Give your ideas some legs: the positive effect of walking on creative thinking.” J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2014 Jul;40(4):1142-52.

Owen, et al. “Too Much Sitting: The Population-Health Science of Sedentary Behavior.” Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010 Jul; 38(3): 105–113.

Palma, B.D. & Tufik, S., Increased disease activity is associated with altered sleep architecture in an experimental model of systemic lupus erythematosus, Sleep. 2010 Sep;33(9):1244-8.

Palma, B.D., et al., Effects of sleep deprivation on the development of autoimmune disease in an experimental model of systemic lupus erythematosus, Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006 Nov;291(5):R1527-32.

Panter-Brick. “Sexual division of labor: energetic and evolutionary scenarios.” Am J Hum Biol. 2002 Sep-Oct;14(5):627-40.

Pontzer, et al. “Hunter-Gatherer Energetics and Human Obesity.” PLoS One. 2012; 7(7): e40503.

Pontzer, et al. “Energy expenditure and activity among Hadza hunter-gatherers.” Am J Hum Biol. 2015 Mar 30. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22711.

Ranjbaran, Z., et al., The relevance of sleep abnormalities to chronic inflammatory conditions, Inflamm Res. 2007 Feb;56(2):51-7.

Reynolds AC, et al., Impact of five nights of sleep restriction on glucose metabolism, leptin and testosterone in young adult men, PLoS One. 2012;7(7)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) “2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans”

van Leeuwen WM, et al., Sleep restriction increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases by augmenting proinflammatory responses through IL-17 and CRP, PLoS One. 2009;4(2)

Veerman, et al. “Television viewing time and reduced life expectancy: a life table analysis.” Br J Sports Med doi:10.1136/bjsm.2011.085662

Wu, G., et al., Understanding resilience, Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:10

Zawieja D. “Contractile Physiology of Lymphatics.” Lymphat Res Biol. 2009 Jun; 7(2): 87–96.